Cima da Conegliano

near Treviso, about 1459 - 1517, Conegliano or Venice

Cima da Conegliano(, Giovanni Battista)

(b Conegliano, nr Treviso, ?1459–60; d Conegliano or Venice, Sept 1517 or 1518).

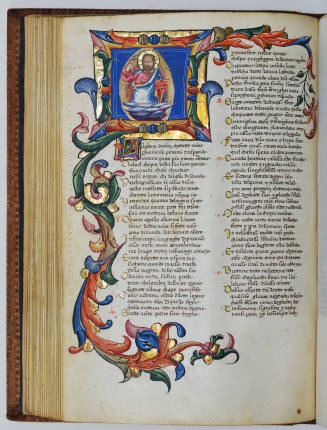

Italian painter. He belonged to the generation between Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione and was one of the leading painters of early Renaissance Venice. His major works, several of which are signed, are almost all church altarpieces, usually depicting the Virgin and Child enthroned with saints; he also produced a large number of smaller half-length Madonnas. His autograph paintings are executed with great sensitivity and consummate craftsmanship. Fundamental to his artistic formation was the style that Bellini had evolved by the 1470s and 1480s; other important influences were Antonello da Messina and Alvise Vivarini. Although Cima was always capable of modest innovation, his style did not undergo any radical alteration during a career of some 30 years, and his response to the growing taste for Giorgionesque works from the early 16th century remained superficial. He seems to have maintained a sizeable workshop, but there is no evidence that he trained any major artist and he had little long-term influence on the course of Venetian painting.

Cima’s work presents few serious problems either of attribution or dating. His style is readily recognizable and has rarely been confused with that of other major artists; the only real doubts relate to questions of workshop collaboration. A number of signed and dated works survives from all phases of his career, and several major works may be dated on external evidence. They show that Cima’s style changed perceptibly but not radically, and although his later works show a certain softening of internal contours and a deeper and richer colour range, he remained largely impervious to the style that Bellini evolved after c. 1500.

1. Life and work.

Cima’s name provides an accurate indication of his geographical and social origins: he came from a family of cimatori (cloth-shearers) in the small town of Conegliano on the Venetian mainland. He is first recorded in his father’s tax returns in 1473, by which date he must have reached the age of 14. His entire career was spent in Venice, where he is first definitely recorded in 1492, but he maintained close links with his home town throughout his life, keeping a house there and later acquiring land in the area. This enduring contact with the Venetian terra firma may account for the important and distinctive part played by landscape in his art from early maturity onwards.

Cima may have served an apprenticeship with one of the painters active in Conegliano in the 1470s, but they were all provincial mediocrities, and he is likely to have gravitated to a more important centre by the early 1480s. Some critics have identified this as Vicenza, and his master as Bartolomeo Montagna, since Cima’s earliest dated work, the Virgin and Child with SS James and Jerome (Vicenza, Mus. Civ. A. & Stor.), was painted for the church of S Bartolomeo, Vicenza, in 1489. But Cima would have reached the status of independent master long before then, and none of his works that appear to pre-date the Vicenza altarpiece reveals any response to the art of Montagna. The basis for Cima’s own style is clearly that of Giovanni Bellini, and, whether or not he was trained in Bellini’s studio, he must have been closely acquainted with Bellini’s major works in Venice at an early stage in his career. Consistent with this supposition is the theory that Cima trained under Alvise Vivarini, for his earliest works contain echoes and near quotations from both artists. If Cima was resident in Venice by the early to mid-1480s, he may well be the ‘magister Zambatista pictor’ who is recorded as having sent a confraternity standard from Venice to Conegliano in 1486.

At the beginning of his career Cima’s style more closely resembled relief sculpture than free-standing statuary. In an early Virgin and Child (c. 1485–6; Philadelphia, PA, Mus. A.) the figures occupy a shallow space, the shadows are pale and the folds of drapery are treated more as an abstract pattern of lines than as a naturalistic representation of the fall of cloth. Similar features appear in an early altarpiece, the Olera Polyptych (c. 1486–8; Olera, Parish Church), in which the saints look slender and fragile, showing angularities of form that may derive from Alvise Vivarini.

Around this time Cima began to produce the first of the altarpieces that make up the main body of his work. The earliest examples were all painted for towns and villages in the Veneto—Oderzo (near Treviso) as well as Conegliano—and this region remained one of his most important sources of patronage. The earliest of his Venetian altarpieces show him already at the height of his powers. St John the Baptist with SS Peter, Mark, Jerome and Paul (c. 1493–5; Venice, Madonna dell’Orto) well illustrates his main sources of inspiration. Its basic composition follows the principles laid down for sacre conversazioni by Giovanni Bellini in his altarpieces for SS Giovanni e Paolo (c. 1470; destr. 1867) and S Giobbe (c. 1480; Venice, Accad.; see fig.). The picture field is a tall, round-topped rectangle, with the group of saints arranged symmetrically under vaulted architecture, the forms of which are complemented by the real stone frame. The central saint, John the Baptist, is set slightly higher than his companions, with his head forming the apex of a compositional pyramid. The figures are disposed with a sense of easy spaciousness, their features, limbs and draperies modelled with crisp clarity in the sharply directed light. Cima’s picture also has much in common with those of Bellini in its emotional tenor, the general mood one of calm meditation and gentle devotion. Characteristic of Cima himself is the rustic sturdiness of the figure types; and in contrast to Bellini’s typically ecclesiastical interiors, Cima’s architectural structure is ruinous, with vegetation encroaching into the open vault and a pleasant view of the Veneto countryside visible in the background. The formality and stability of Bellini prototypes is further reduced by the picturesque asymmetry of the architectural arrangement, which is presented obliquely, with the three columns on the right loosely balanced against the pier and tree on the left. Although the construction is somewhat improbable in functional terms, it is rendered delightful by the minute attention paid to the finely chiselled masonry, the variety of plants and flowers, and, above all, by the pervasive sense of fresh air and natural light.

Many of the same qualities are apparent in a characteristic Virgin and Child (c. 1495; Bologna, Pin. N.), formerly in S Giovanni in Monte, Bologna. Again, Cima’s starting-point is a formula established by Giovanni Bellini, with the Virgin seen in half-length behind a marble parapet, and a view of landscape behind. The painting also shows Cima’s intelligent understanding of the formal problems that had preoccupied Bellini during his phase of active response to the art of Antonello da Messina during the 1470s and 1480s; the figures are conceived as two contrasting masses, and the volumetric quality of every shape is stressed by the carefully directed light. Also typical of Cima is the unaffected, countrified look of the figures, who lack the spiritual gravity of those of Bellini; and Bellini’s customary back-cloth of honour, a regal symbol, is replaced by a landscape view agreeably reminiscent of the hilly countryside of Cima’s homeland.

During the 1490s, when Giovanni Bellini was occupied largely with the decoration of the Doge’s Palace, Cima became the leading exponent of altar painting in Venice. Even after the emergence c. 1505 of a younger and radically innovative generation that included Giorgione, Titian, Sebastiano del Piombo, Lorenzo Lotto and Palma Vecchio, Cima maintained his leading position and remained much in demand as a painter of devotional works. Among his largest and most imposing altarpieces are those painted for the Venetian churches of S Maria della Carità (c. 1499–1501; Venice, Accad.), Corpus Domini (c. 1505–6; Milan, Brera) and S Maria dei Carmini (c. 1509–11; in situ), all of which were commissioned by wealthy, though not noble, Venetian citizens closely involved in the devotional and charitable activities of the scuole grandi.

Although none of Cima’s early altarpieces includes landscape background, the large-scale Baptism in S Giovanni in Bragora, Venice, is set in a landscape painted with complete confidence and mastery. This important commission for the church’s high altarpiece was commissioned in 1492. The middle distance and background are filled with sharply focused natural detail and human incident: ducks on the river, sheep in the fields, boatmen and horsemen; yet these details are not obtrusive because they are imposed on to a compositional structure of perfect logic and clarity, which leads the eye gently backwards down the twisting river and up the hilly paths into the distant background. Together with the radiant light, these formal devices derive from works by Giovanni Bellini of the 1480s such as the Ecstasy of St Francis (New York, Frick) and the Transfiguration (Naples, Capodimonte), but Cima succeeded in transforming them into something entirely his own.

During the 1490s Cima also worked for patrons in Emilia. The Lamentation (c. 1495–7; Modena, Gal. & Mus. Estense) once belonged to Alberto Pio (1475–1531), Lord of Carpi, near Modena, an ardent supporter of humanist learning and a regular visitor to Venice. Stylistic evidence indicates that this picture was soon followed by the first of three altarpieces that Cima painted for churches in Parma: the Virgin and Child with SS Michael and Andrew (c. 1496–8; Parma, G.N.), in which Cima used a particularly daring asymmetrical composition, moving the architecture entirely to one side and balancing it against a view of a distant hill city on the other. The figure of St Michael shows a refinement and sophistication that marks a departure from the rustic simplicity of the Madonna dell’Orto saints and that may reflect contact with the art of Pietro Perugino. If Cima did visit Parma in connection with this commission, he may have stopped in Bologna on the way and seen Perugino’s Virgin in Glory with Four Saints (c. ?1496; Bologna, Pin. N.), painted for S Giovanni in Monte. Such an influence might also account for the novel effects of contrapposto in the work.

The twisting poses of the figures and the relaxed asymmetry of the composition are important precedents for the dynamically conceived altarpieces of Titian and Sebastiano del Piombo at the beginning of their careers. But Cima did not pursue his own innovations, and major works of the first decade of the 16th century such as the altarpiece from the Corpus Domini in Venice, St Peter Martyr with SS Nicholas and Benedict (c. 1505–6; Milan, Brera), reveal his essentially conservative temperament. Although the late afternoon pastoral landscape in the background has an elegiac quality that is rather different from the morning freshness of the earlier Baptism and that perhaps owes something to Giorgione, the architectural foreground is again entirely symmetrical, with the three saints correspondingly calm and static, themselves resembling architectural members. It is as if Cima were consciously renewing the springs of his art by turning back not just to the earlier Giovanni Bellini but to Antonello da Messina. Cima’s early works show little direct influence from the pictures that Antonello had left in Venice during his visit of 1475–6, but the rigorous simplification of the head and robes of the central figure of St Peter Martyr and the geometric harmony of the composition seem to reflect a careful study of Antonello’s great altarpiece for S Cassiano (1475–6; fragment in Vienna, Ksthist. Mus.; see fig.).

The Virgin and Child with SS John the Baptist, Cosmas, Damian, Apollonia, Catherine and John the Evangelist (c. 1506–8; Parma, G.N.) was commissioned by Canon Bartolomeo Montini for his funerary chapel in Parma Cathedral. Montini is of particular interest since he was closely related to two of the leading patrons of art in the city, the Marchese Scipione della Rosa and Scipione’s sister-in-law, the abbess Giovanna da Piacenza, both early supporters of Correggio. There is some evidence to suggest that a pair of exquisite mythological tondi by Cima, Endymion Asleep and the Judgement of Midas (both c. 1505–10; Parma, G.N.), were also commissioned by a member of this circle. Cima produced only a handful of works with mythological subjects, all of them on a small scale, and all apparently made to decorate cassoni or other items of furniture. They are important early examples of a genre that was to become closely associated with the great Venetian painters of the 16th century, especially as Cima’s earliest examples, a pair of panels with scenes from the Legend of Theseus (c. 1495–7; Zurich, priv. col., and Milan, Brera, on dep. Milan, Mus. Poldi Pezzoli; see Humfrey, 1981), appear to pre-date the earliest examples by Giovanni Bellini and Giorgione. But by far the most numerous domestic pictures produced by Cima and his shop were half-length paintings of the Virgin and Child, with or without accompanying saints. Such pictures were clearly painted to meet a heavy popular demand for small panels with devotional subjects and often may have been sold on the open market.

The best of Cima’s late works, for example the third of the Parma altarpieces, the Virgin and Child with SS John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene (c. 1511–13; Paris, Louvre), similarly show only superficial concessions to modernity within a framework of intelligent conservatism. The landscape is lusher and more generalized than that of the St Peter Martyr altarpiece, the shadows deeper and the saints—a Giorgionesque Baptist and a Magdalene in the style of Palma Vecchio—move forward to adore the Child in a way that imparts a new fervour to the mood and a new animation to the composition. But there remains a duality between the figures and their environment, and the literalism and dependence on linear perspective to create the illusion of space is still in the spirit of the 15th century. Forms are conceived additively rather than organically, and the attention to small-scale detail is, by 16th-century standards, pedantic. Yet Cima had not lost self-confidence, nor had he relaxed his high standards of craftsmanship; and, no less than are his more progressive works of the 1490s, the altarpiece is one of great serenity and beauty.

Documents relating to Cima’s life are scarce: he was twice married and had eight children, none of whom followed their father’s profession. In 1507–9 he was involved in a lawsuit over his Incredulity of Thomas (1502–4; London, N.G.), a large altarpiece painted for a flagellant community in Portogruaro. At a meeting of the painters’ guild in 1511, Cima proposed that figure painters be accorded a status superior to that of decorative painters, but this was summarily dismissed. In 1514 he was living in an apartment in the Palazzo Corner Piscopia (later Loredan), near the Rialto Bridge in the parish of S Luca. It is not clear how often and how widely he travelled outside Venice; he may not always have accompanied his altarpieces to distant destinations in the Veneto, making use instead of Venice’s well-developed systems of transport, but when establishing contact with important patrons like those in Parma, it seems likely that he made the journey in person. He certainly made frequent visits to Conegliano. A document relating to his death states that he was buried alli fra menori (in the church of the friars minor, i.e. Franciscans), which may refer to the Frari in Venice or to S Francesco in Conegliano.

2. Working methods and technique.

Cima’s practice was based on that of Giovanni Bellini in matters of workshop procedure and pictorial technique, as well as of style. Almost without exception his pictures were painted on gesso-primed panels, and from early maturity onwards he used oil as his principal medium. It is evident from the quantity, and also from the rather variable quality, of surviving works in Cima’s style that he made extensive use of workshop assistants. The identity of some of these, including Andrea Busati, Girolamo da Udine, Pasqualino Veneto and Anton Maria da Carpi (fl 1495), may be inferred from the occasional work inscribed with their signatures.

Cima’s working methods are well illustrated by a small Virgin and Child with SS Andrew and Peter (Edinburgh, N.G.), which has survived in an unfinished state (see Plesters, 1985). The ground has been identified as true gesso, on top of which Cima made an underdrawing with the tip of the brush in black gall ink, carefully mapping out the entire composition. The internal modelling of the forms, in particular of the draperies, is rendered with finely detailed parallel hatching and shading. In some of the forms colour had not yet been applied; elsewhere the artist had begun to apply the paint, bound with linseed oil in a leanish mixture, in a series of thin, even layers kept strictly within the contours of the forms. None of the colour planes has a final paint layer, and hence they also lack the glazes and highlights that give the surfaces of objects in Cima’s completed pictures their characteristic glow.

Cima’s slow and deliberate method of painting, carefully following his detailed underdrawing, has more in common with traditional Italian tempera techniques than with the more flexible and spontaneous method of oil painting developed by Titian during Cima’s lifetime. His works up to c. 1490 all seem to have been painted in tempera; thereafter he evidently combined both media in individual works. It is clear from the increasingly soft and fluent tonal transitions that appear in his works of the 1490s that by the end of the decade he had acquired full confidence in the use of the new oil medium.

Cima’s dependence on underdrawings, which excluded all but the most minor pentiments in his paintings, indicates that each new project must have been preceded by numerous preparatory drawings on paper. Although no more than eight or nine of his drawings survive, they illustrate several different stages of the planning process, from the full-length St Jerome (Florence, Uffizi), a relatively sketchy study for the modelling of St Jerome’s draperies in the Vicenza altarpiece of 1489, to the extremely detailed Head of St Jerome (London, BM), which seems to be an ‘auxiliary’ cartoon for the Madonna of the Orange Tree (c. 1496–8; Venice, Accad.). The drawing of an Enthroned Bishop with Two Saints (Windsor Castle, Berks, Royal Col.) represents a fully evolved compositional study. Drawings would also have played an important role in Cima’s workshop as ricordi or visual records for later re-use or adaptation. The Head of St Jerome may itself be based on a ricordo, since a very similar head had already appeared in the Olera polyptych (c. 1486–8); it is typical of Cima’s method that heads, figures and landscape motifs should make frequent reappearances in later works, sometimes after ten years or more. This habit of self-repetition, which was a useful expedient in meeting the popular demand for his works, was criticized by Vasari in relation to Cima’s contemporary, Perugino; but on the whole Cima managed to avoid the obvious danger of monotony by the sheer skill and meticulous craftsmanship of his pictorial execution.

3. Critical reception and posthumous reputation.

The large output of Cima’s workshop, which did not decrease towards the end of his life, shows that his works were in high demand. Even after Giorgione’s death, Cima continued to receive important metropolitan commissions such as that for the Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1509–11; Venice, S Maria dei Carmini). His typical customers (members of the Venetian citizen class, devotional confraternities and mainland parishes), however, were more likely to have been attracted to his art for its devotional than for its purely aesthetic qualities. His solemn, meditative, humanly accessible saints, set within a harmonious architectural foreground against a peaceful sunlit landscape, evidently accorded well with a particular brand of contemporary religiosity. But for collectors and connoisseurs with more sophisticated and secular tastes, Cima’s style must have begun to look old-fashioned soon after 1500. It is significant that Michiel’s Notizia (c. 1520–40), a detailed account of Venetian art collections, does not record a single work by Cima, even though numerous private homes must have possessed examples of his work.

By the mid-16th century ‘Giovanni Battista da Conegliano’ had become little more than a name attached to a handful of signed altarpieces in Venetian churches. Vasari included Cima in his life of ‘Scarpazza’ (Carpaccio), mentioning only the St Peter Martyr altarpiece in the church of Corpus Domini, and referring to him as a pupil of Giovanni Bellini. Vasari also provided the mistaken information that Cima died young, thus misleading critics for another three centuries. The mistake may, however, have been based on the astute visual observation that Cima followed Bellini’s middle style, not his late one. The various Venetian sources of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries all give Cima respectful but brief mention and sometimes confuse his works with those of Bellini.

Cima’s reputation was revived in the 19th century, along with that of many of his contemporaries. He was a favourite painter of John Ruskin, whose Modern Painters (London, 1843) contains a lyrical passage about the plants in the Madonna dell’Orto altarpiece. The first serious and detailed study of Cima’s art was made by Crowe and Cavalcaselle (1871). This was followed by Botteon’s and Aliprandi’s monograph (1893), which is likely to remain the fullest biographical account. A significant landmark for the wider appreciation of Cima’s art was the ambitious exhibition held in Treviso in 1962. In 1977 the artist’s birthplace became the headquarters of a society founded in his honour, the Fondazione Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano.

Bibliography

DBI; Thieme–Becker

General works

J. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle: A History of Painting in North Italy (London, 1871, rev. 1912)

L. Venturi: Le origini della pittura veneziana (Venice, 1907)

P. Schubring: Cassoni (Leipzig, 1915, 2/1923)

A. Venturi: Storia, ii/4 (1915/R 1967), pp. 500–51

B. Berenson: Venetian Painting in America (New York, 1916)

H. Tietze and E. Tietze-Conrat: The Drawings of the Venetian Painters in the 15th and 16th Centuries, 2 vols (New York, 1944)

R. Longhi: Viatico per cinque secoli di pittura veneziana (Florence, 1946)

M. Davies: The Earlier Italian Schools, London, N.G. cat. (London, 1951, 2/1961/R 1986)

S. Moschini Marconi: Opere d’arte dei secoli XIV e XV, Venice, Accad. cat. (Rome, 1955)

B. Berenson: Venetian School (1957), pp. 64–8

M. Bonicatti: Aspetti dell’umanesimo nella pittura veneta dal 1455 al 1515 (Rome, 1964)

M. Kemp: Cima (London, 1967)

H. W. van Os and others, eds: The Early Venetian Paintings in Holland (Maarssen, 1978)

M. Natale: Musei e Gallerie di Milano: Museo Poldi Pezzoli, dipinti (Milan, 1982)

M. Lucco: ‘Venezia fra quattro e cinquecento’, Storia dell’arte italiana, ed. G. Bollati and P. Fossati, v (Turin, 1983), p. 459

N. Huse and W. Wolters: Venedig: Die Kunst der Renaissance (Munich, 1986)

P. Humfrey: ‘Competitive Devotions: The Venetian Scuole piccole as Donors of Altarpieces in the Years around 1500’, A. Bull., lxx (1988), pp. 401–23

P. Humfrey: The Altarpiece in Renaissance Venice (New Haven and London, 1993)

B. Aikema and L. B. Brown, eds: Renaissance Venice and the North: Crosscurrents in the Time of Bellini, Dürer, and Titian (New York, 2000)

Early sources

M. A. Michiel: Notizia d’opere di disegno (c. 1520–40); ed. G. Frizzoni (Bologna, 1884) [records S Maria della Carità altarpiece]

G. Vasari: Vite (1550, rev. 2/1568); ed. G. Milanesi (1878–85), iii, p. 645

F. Sansovino: Venetia città nobilissima et singolare (Venice, 1581, rev. 2/1663)

C. Ridolfi: Meraviglie (1648); ed. D. von Hadeln (1914–24/R 1965), i, pp. 76–7

M. Boschini: Le minere della pittura (Venice, 1663)

A. M. Zanetti: Della pittura veneziana e delle opere pubbliche de’ veneziani maestri (Venice, 1771)

F. Malvolti: Catalogo delle migliori pitture esistenti nella città e territorio di Conegliano (1774); ed. L. Menegazzi (Treviso, 1964)

D. M. Federici: Memorie trevigiane sulle opere di disegno, 2 vols (Venice, 1803)

G. A. Moschini: Guida per la città di Venezia, 2 vols (Venice, 1815)

G. Caprin: Istria nobilissima, 2 vols (Trieste, 1904), p. 135 [documents for Capodistria altarpiece]

Monographs, exhibition catalogues and symposia

V. Botteon and A. Aliprandi: Ricerche intorno alla vita e alle opere di Giambattista Cima (Conegliano, 1893/R Bologna, 1977)

R. Burckhardt: Cima da Conegliano (Leipzig, 1905)

L. Coletti: Cima da Conegliano (Venice, 1959)

Cima da Conegliano (exh. cat., ed. L. Menegazzi; Treviso, Pal. Trecento, 1962)

Prov. Treviso, v (1962) [issue dedicated to Cima]

S. Coltelacci, I. Reho and M. Lattanzi: ‘Problemi di iconologia nelle immagini sacre: Venezia c. 1490–1510’, Giorgione e la cultura veneta tra ’400 e ’500; Atti del Convegno: Roma, 1978, pp. 97–103

Giorgione a Venezia (exh. cat., Venice, Accad. Pitt. & Scul., 1978)

L. Menegazzi: Cima da Conegliano (Treviso, 1981)

P. Humfrey: Cima da Conegliano (Cambridge, 1983) [illustrations and documents]

Venezia cinquecento, iv/7–8 (Conegliano, 1993) [papers given at conference on Cima]

Bellini, Giorgione, Titian and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting (exh. cat., ed. D. A. Brown and S. Ferino-Pagden; Washington, DC and Vienna, 2006)

Specialist studies

V. Lasareff: ‘Opere nuove o poco note di Cima da Conegliano’, A. Ven., xi (1957), pp. 39–52

J. Bia?ostocki: ‘“Opus quinque dierum”: Dürer’s Christ among the Doctors and its Sources’, J. Warb. & Court. Inst., xxii (1959), pp. 17–34

A. C. Quintavalle: ‘Cima da Conegliano e Parma’, Aurea Parma, xliv (1960), pp. 27–30

A. Ballarin: ‘Cima at Treviso’, Burl. Mag., civ (1962), pp. 483–6

R. Pallucchini: ‘Appunti alla mostra di Cima da Conegliano’, A. Ven., xvi (1962), pp. 221–7

L. Vertova: ‘The Cima Exhibition: A Festival at Treviso’, Apollo, lxxvi (1962), pp. 716–19

I. Kühnel-Kunze: ‘Ein Frühwerk von Cima’, A. Ven., xvii (1963), pp. 27–34

R. Marini: ‘Cima e la sua problematica’, Emporium, cxxxvii (1963), pp. 147–58

R. Grönwoldt: ‘Studies of Italian Textiles II: Source Groups of Renaissance Orphreys of Venetian Origin’, Burl. Mag., cvii (1965), pp. 231–40

P. Humfrey: ‘Cima da Conegliano at San Bartolomeo in Vicenza’, A. Ven., xxxi (1977), pp. 176–81

P. Humfrey: ‘Cima da Conegliano and Alberto Pio’, Paragone, xxix/341 (1978), pp. 86–97

P. Humfrey: ‘Cima’s Altarpiece in the Madonna dell’Orto’, A. Ven., xxxiii (1979), pp. 122–5

P. Humfrey: ‘Cima da Conegliano, Sebastiano Mariani and Alvise Vivarini at the East End of S Giovanni in Bragora in Venice’, A. Bull., lxii (1980), pp. 350–63

P. Humfrey: ‘Two Fragments from a Theseus Cassone by Cima’, Burl. Mag., cxxiii (1981), pp. 477–8

P. Humfrey: ‘Cima da Conegliano a Parma’, Saggi & Mem. Stor. A., xiii (1982), pp. 35–46

J. Plesters: Cima da Conegliano, the Virgin and Child with SS Andrew and Peter: Notes on the Examination of the Picture and Analysis of Samples (typescript, Edinburgh, N.G., 1985)

M. Wyld and J. Dunkerton: ‘The Transfer of Cima’s The Incredulity of St Thomas’, N.G. Tech. Bull., ix (1985), pp. 38–59

Disegni veneti di collezioni olandesi (exh. cat., ed. B. Aikema and B. Meijer; Venice, Fond. Cini, 1985), pp. 32–3 [sheet by Cima in Rotterdam]

Master Prints: Fifteenth to Nineteenth Century (sale cat., ed. R. Bromberg; London, Colnaghi & Co., 1985), p. 49 [tentative attribution to Cima of engraving in Mantegna’s style]

J. Dunkerton and A. Roy: ‘The Technique and Restoration of Cima’s The Incredulity of S. Thomas’, N.G. Tech. Bull., x (1986), pp. 4–27

P. Humfrey: ‘Some Additions to the Cima Catalogue’, A. Ven., xl (1986), pp. 154–6

G. J. van der Sman: ‘Uno studio iconologico sull’ Endimione dormiente e sul Giudizio di Mida di Cima da Conegliano: Pittura, poesia e musica nel primo cinquecento’, Stor. A., 58 (1986), pp. 197–203

E. Martini: ‘Di alcune opere di Cima da Conegliano’, Arte Doc., iv (1990), pp. 76–81

E. Manikowska: ‘Cristo tra i dottori di Cima da Conegliano come invenzione rinascimentale’, Bull. Mus. N. Varsovie, xli (2000), pp. 73–84

J. Dunkerton: ‘The Restoration of Two Panels by Cima da Conegliano from the Wallace Collection’, N.G. Tech. Bull., xxi (2000), pp. 58–69

C. Del Bravo: ‘Due veneti’, Opere e giorni: Studi su mille anni di arte europa: Dedicati a Max Seidel (Venice, 2001), pp. 413–20

G. Scarcia, ed.: Il polittico di Cima da Conegliano a Miglionico (Naples, 2002)

E. Daffra and M. Ceriana: ‘Il polittico di San Bartolomeo di Cima da Conegliano’, A. Ven., lxi (2004), pp. 28–69

E. Daffra, ed.: Inauratam et ornatam: Il polittico di Cima da Conegliano a Olera (Azzano San Paolo, 2005)

Peter Humfrey

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Venice, about 1460 - about 1526, Venice

Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales, 1843 - 1912, Venice

Albino, Italy, about 1525 - 1578

Venice, about 1430-1435 - before 1495, Ascoli Piceno

Florence, about 1456 - 1536, Florence

Siena, 1447 - 1500, Siena