Bernardo Daddi

Florence, about 1280 - 1348, Florence

1. Life and work.

(i) Early work, before c. 1330.

According to the documents of his matriculation in the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, Daddi’s career as a painter may have begun early in the 1320s. His first known work is a panel with St Benedict (ex-Brunelli priv. col., Milan), which is solemn in its form, rigid and sparing in line, with strong chiaroscuro modelling. These qualities characterize a stylistically homogeneous group of works, including a polyptych of the Virgin and Child with Four Saints (Parma, G.N.; Parma, priv. col.), a polyptych in the parish church at Lucarelli (nr Radda in Chianti), two panels from a dispersed polyptych, with the Virgin and Child (Rome, Pin. Vaticana) and St Mary Magdalene (New York, priv. col.), and the frescoes of the Martyrdoms of SS Lawrence and Stephen in the Pulci Beraldi Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence (Daddi’s only known painting in that medium, attributed to him by Vasari). These works show a strong debt to Giotto in their firm, three-dimensional construction and in the clear modelling, achieved through a pronounced use of chiaroscuro. They also show strong connections with the work of such painters as Buffalmacco and the Master of S Martino alla Palma (fl 1315–40).

Daddi’s art reached an expressive peak at the end of the 1320s with the signed triptych of the Virgin and Child with SS Nicholas and Matthew (1328; Florence, Uffizi). This painting recalls the most classical of Giotto’s paintings (e.g. the frescoes in the Peruzzi Chapel, Santa Croce, Florence), and it shows that Daddi was familiar with Giotto’s work but that he did not follow the style slavishly, choosing the most suitable ideas suggested by the many aspects of Giotto’s painting and that of such artists in his circle as Taddeo Gaddi. Daddi’s work was strongly influenced by Gaddi’s severe and rigorous style, softened by Gothic effects in line and colour, especially at the time of the latter’s most important work, the frescoes (begun c. 1328) in the Baroncelli Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence. This is evident in the Virgin in S Pietro, Lecore, and in such large single-panel altarpieces as that of St Michael in S Michele, Crespina, or in another badly damaged one in Finland (Joensuu, A. Mus.).

(ii) Mature work, after c. 1330.

The importance of Daddi’s workshop began to emerge in the 1330s; in response to demand it specialized in panel painting, mostly on a small scale. Some monumental works were also produced, however, for example St Paul (1333; Washington, DC, N.G.A.) and a polyptych fragment with SS John and Paul (New York, priv. col.). In the latter work the figures, depicted in profile, show the wide variety of compositional and spatial solutions used by Daddi to extend the limits imposed by the wooden structure of the polyptych. He is also known to have been involved in such important public projects as the polyptych (untraced) commissioned in 1335 for the S Bernardo Chapel in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence.

Daddi and his workshop produced innumerable small altarpieces for private devotion, most commonly with representations of the Virgin and Child Enthroned, the Nativity, and the Crucifixion, sometimes personalized with a few thematic variations. Daddi’s most individual qualities are to be found in some of these works, which include two panels from triptychs (Naples, Capodimonte, and Florence, Uffizi, 8564, respectively); a triptych (13(?33); Florence, Mus. Bigallo); a series of similar altarpieces (e.g. Washington, DC, Dumbarton Oaks; New York, Met., 32.1000.70 and 49.190.12; Prague, N.G., ?ternberk Pal., O 11967–9; Altenburg, Staatl. Lindenau-Mus.); and two predellas, one with scenes from the Life of St Cecilia (divided between Kraków, N. Mus.; Pisa, Mus. N. S Matteo; priv. col.), and another (divided between Berlin, Gemäldegal.; New Haven, CT, Yale U.; Paris, Mus. A. Déc.; Pozna?, N. Mus.) from a Dominican triptych (untraced) painted for S Maria Novella, Florence, in 1338. Such works as the two triptychs dated 1338 (Edinburgh, N.G., and U. London, Courtauld Inst. Gals) display the highest level of technical achievement and lyric inspiration. These small-scale commissions clearly provided Daddi with the format best suited to his rich narrative and illustrative skills. His fluent line and varied, brilliant colouring create precious, captivating images of an expressive character, arranged in clear and successful narrative sequences.

Daddi’s workshop also owed its success to the sweet, pleasing quality of the figures of the Virgin and Child (e.g. Florence, I Tatti), depicted in tender attitudes similar to those in contemporary Sienese painting. Further echoes of the close contacts that existed in the 1330s between Sienese and Florentine painters, especially through Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, can be discerned in the lyrical accent and the controlled sense of drama in Daddi’s Crucifixions (e.g. Altenburg, Staatl. Lindenau-Mus.). His rich inventiveness in coining iconographic novelties is displayed especially in predella panels, for example that with scenes from the Legend of the Sacra Cintola (Prato, Mus. Com.) and the predella with scenes of the Life of St Stephen (Rome, Pin. Vaticana).

Daddi’s preference for small-scale work can be seen as part of a trend in Florentine painting, defined by Offner, which included Lippo di Benivieni, the Master of the Codex of S George, and Pacino di Bonaguida, artists who according to Offner followed a ‘miniaturist tendency’ in contrast to Giotto’s more monumental style. This trend would certainly have been influenced by the profound stylistic innovations brought to Florence by Pietro Lorenzetti with such works as the altarpiece of the Beata Umiltà (Florence, Uffizi), attributed to him by most scholars, or by Andrea Pisano who was then working on the first doors at Florence Baptistery.

Daddi successfully introduced these ideas into Giotto’s workshop, as is shown by Taddeo Gaddi’s small altarpiece (1334; Berlin, Gemäldegal., 1079–81) and the one by Maso di Banco (New York, Brooklyn Mus.), which are variations or near-replicas of Daddi’s Bigallo Triptych, considered the prototype. Daddi’s role in Giotto’s workshop was clearly not a subordinate one. This would seem to be further confirmed by Daddi’s position in relation to such a leading artist as Maso di Banco, whom Longhi regarded as the originator of many formal innovations. In fact, if the careers of Daddi and Gaddi ran in parallel, it is possible that Maso was trained in Daddi’s workshop (Volpe). The altarpiece of 1336 in S Giorgio a Ruballa, near Florence, has always been attributed to Daddi’s workshop and in the late 20th century to the young Andrea di Cione (also known as Orcagna; see Bellosi); if it was the work of Maso, as seems probable (Volpe, Boskovits), this would suggest that Maso learnt his trade from Daddi rather than in a more narrowly Giottesque environment.

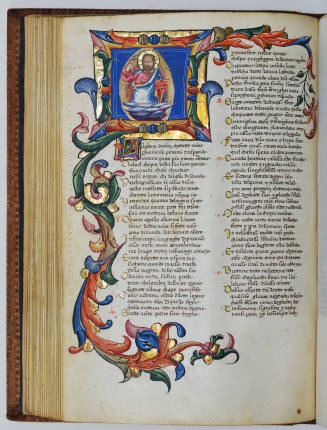

Bernardo Daddi and assistant: Assumption of the Virgin, fragment of...In 1339 Daddi enrolled in the Accademia di S Luca. The works of his last period are characterized by an overall monumentality of plan (see fig.), for example the complex polyptych with several registers (partly Florence, Uffizi) made for Florence Cathedral and later in S Pancrazio. Two predellas were assigned by Vasari to this work: the Life of the Virgin (Florence, Uffizi; see fig. [not available online]; London, Buckingham Pal., Royal Col.) and the Life of St Reparata (Brussels, Mme Paul Pèchere priv. col.; Cologne, priv. col.; New York, Met.). Other late works show his concise rendering of volumes, with strongly emphasized pastiglia decoration in the haloes (e.g. Virgin and Child, 1346–7; Florence, Orsanmichele). These late works also include the dismembered polyptych (Florence, Uffizi, 8706–7; ex-Drury-Lowe Col., Locko Park; Milan, priv. col.; ex-Lanckoro?ski priv. col., Vienna) of the early 1340s from S Maria del Carmine, Florence, and Daddi’s last known work, a polyptych showing the Crucifixion with Saints (1348; U. London, Courtauld Inst. Gals), from S Giorgio a Ruballa. The design of the latter, with pairs of saints flanking a central scene, heralds the departure from the standard, rigidly compartmentalized polyptych type, anticipating the work of Andrea di Cione.

2. Critical reception. and posthumous reputation

Bernardo Daddi is not given much attention in the early sources; he is mentioned only by Vasari, in connection with the Pulci Berardi frescoes in Santa Croce. Only through studies by Passerini and Milanesi has it been possible to associate the signature ‘Bernardus de Florentia’ with the Bernardo di Daddo documented in the guild records (Vitzthum). The serial character of Daddi’s work has negatively influenced the critical evaluation of the vast production attributable to him and his circle. Longhi, for example, called him a ‘clockwork nightingale’ of painting, ‘mediocre’ even if ‘much loved’. Offner, by contrast, restricted the catalogue of his works to the autograph paintings and those of the highest quality, praising their style and the richness of their lyrical inspiration. He presented Daddi as an individual and highly refined painter, the greatest after Giotto in 14th-century Florence. In line with the reasoning of Boskovits (1984), however, it seems wiser to accept the more inclusive catalogue of the paintings of Daddi and his workshop, despite a certain repetitiveness and some instances of less-skilled execution.

Two artists have been identified as Daddi’s collaborators: the ‘Assistant of Daddi’ (Offner), a painter with a limited sense of form but with considerable illustrative skills, to whom Offner assigned such works as a Crucifix (Florence, Accad., 442) and a St Catherine (Florence, Accad., 3457), and the Master of S Polo in Chianti (Tartuferi), a painter of very modest abilities who was also a poor imitator of Taddeo Gaddi’s style. Daddi’s influence on other contemporary painters was significant. One of the figures closest to him in style has been called the ‘Maestro daddesco’. This artist, an illuminator of notable skill, spent his early career (c. 1315) working on choir-books (Rome, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme) for the Badia a Settimo (nr Florence), together with the Master of the Codex of S George. Thus, rather than being a follower, he was first a precursor of Daddi, while later the two artists’ works show a mutual influence. Another, the refined, archaizing Master of S Martino alla Palma, became a follower of Daddi only towards the end of his career.

In the middle of the 14th century, even after Daddi’s death, the influence of his style had a strong resonance in Florence. His last formal innovations in volumetric and chromatic synthesis influenced the brothers Andrea Orcagna and Nardo di Cione and were successfully adopted by such painters as Puccio di Simone and Allegretto Nuzi. During their period of collaboration these two artists adapted Daddi’s late style to solutions that were even more decorative, denying any corporeal aspect. This is evident in their joint works produced in the Marches, for example St Anthony Abbot (Fabriano, Pin Civ. Mus. Arazzi) and a triptych of the Virgin and Child with Saints and Angels (1354; Washington, DC, N.G.A.), also made for a church in Fabriano.

Colnaghi; DBI; Thieme–Becker

G. Vasari: Vite (1550, rev. 2/1568); ed. G. Milanesi (1878–85)

F. Baldinucci: Notizie (1681–1728); ed. F. Ranalli (1845–7)

J. A. Crowe and G. B. Cavalcaselle: A New History of Painting in Italy from the Second to the Sixteenth Century, 2 vols (London, 1864–6, rev. 1904–14)

L. Passerini and G. Milanesi: Del ritratto di Dante Alighieri (Florence, 1865), p. 16

G. Milanesi: ‘Della tavola di Nostra Donna nel tabernacolo d’Or San Michele e del suo vero autore’, Nuova Antol. (Sept 1870), pp. 116–31

C. Frey, ed.: Il libro di Antonio Billi (Berlin, 1872)

C. Frey, ed.: Die Loggia dei Lanzi zu Florenz (Berlin, 1885), p. 315

G. Milanesi: Nuovi documenti per lo studio della storia dell’arte (Florence, 1893)

G. G. Vitzthum: Bernardo Daddi (Leipzig, 1903)

W. Suida: ‘Studien zur Trecentomalerei’, Repert. Kstwiss., xxvii (1904), pp. 385–9

A. Venturi: Storia (1907), v, pp. 508–23

O. Siren: Giotto and some of his Followers, i (Cambridge, 1917), pp. 185–7, 271–2

R. van Marle: Italian Schools (1924), iii, pp. 348–91

E. Sandberg-Vavalà: ‘Opere inedite di Bernardo Daddi’, Cron. A., vi (1927), pp. 1–11

R. Offner and K. Steinweg: Corpus (1930–79) [Bernardo Daddi and his Circle]; rev. M. Boskovits (1989–)

Pittura italiana del duecento e del trecento (exh. cat. by G. Sinibaldi and G. Brunetti, Florence, Uffizi, 1937)

R. Longhi: ‘Qualità e industria in Taddeo Gaddi’, Paragone, x (1959), no. 109, pp. 31–40; no. 111, pp. 3–12

L. Marcucci: Gallerie nazionali di Firenze: I dipinti toscani del secolo XIV (Rome, 1965), pp. 27–49

G. Previtali: Giotto e la sua bottega (Milan, 1967)

I. Hueck: ‘Le matricole dei pittori fiorentini prima e dopo il 1320’, Boll. A., n. s. 2, lvii (1972), pp. 114–21

L. Bellosi: ‘Una precisazione sulla Madonna di Orsanmichele’, Scritti in onore di Ugo Procacci, i (Milan, 1977), pp. 146–51

C. Gardner von Teuffel: ‘The Buttressed Altarpiece: A Forgotten Aspect of Tuscan Fourteenth Century Altarpiece Design’, Jb. Berlin. Mus., xxi (1979), pp. 21–65

C. Volpe: ‘Il lungo percorso del “dipingere dolcissimo e tanto unito”’, Storia dell’arte italiana, ed. F. Zeri, v (Turin, 1983), pp. 229–304

M. Boskovits: Corpus (1984)

R. Offner: The Works of Bernardo Daddi, ed. M. Boskovits (Florence, 1989)

A. Tartuferi: ‘Ipotesi su un pittore fiorentino del trecento: Il maestro di San Polo in Chianti’, Paragone, xl (1989), no. 467, pp. 21–7

L. Monnas: ‘Silk Textiles in the Paintings of Bernardo Daddi, Andrea di Cione and their Followers’, Z. Kstgesch., liii/1 (1990), pp. 39–58

R. Offner: Bernardo Daddi: His Shop and Following, ed. M. Boskovits (Florence, 1991)

A. Padoa Rizzo: ‘Bernardo di Stefano Rosselli, il “Polittico Rucellai” e il “Polittico di San Pancresio” di Bernardo Daddi’, Stud. Stor. A., iv (1993), pp. 211–22

E. Neri Lusanna: ‘Daddi, Bernardo (o di Daddo)’, Enciclopedia dell rte medievale, v (1994), pp. 605–9 [extensive bibliog.]

Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300–1450 (exh. cat., ed. L. B. Kanter; New York, Met., 1994), pp. 177–84

L. Bellosi: ‘Problemi di pitture fiorentine intorno alla metà del trecento’ Atti del covegno in memorie di F. Arcangeli e C. Volpe: Bologna, 1995

D. Finiello Zervas, ed.: Orsanmichele a Firenze, 2 vols (Modena, 1996), pp. 79–98 [extensive bibliog.]

J. Cannon: ‘Viewing Two Paintings by Bernardo Daddi’, Brit. A. J., ii/2 (Winter 2000–01), pp. 68–70

R. Offner: The Fourteenth Century. Bernardo Daddi and his Circle, ed. M. Boskovits (Florence, 2001)

M. Ciatti: La Croce di Bernardo Daddi del Museo Poldi Pezzoli: Ricerche e conservazione (Florence, 2005)

Enrica Neri Lusanna

Grove Art online

Accessed 3/17/14 E. Reluga

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Albino, Italy, about 1525 - 1578

near Treviso, about 1459 - 1517, Conegliano or Venice

Florence, about 1456 - 1536, Florence

Venice, about 1460 - about 1526, Venice

Siena, 1447 - 1500, Siena

Venice, about 1430-1435 - before 1495, Ascoli Piceno

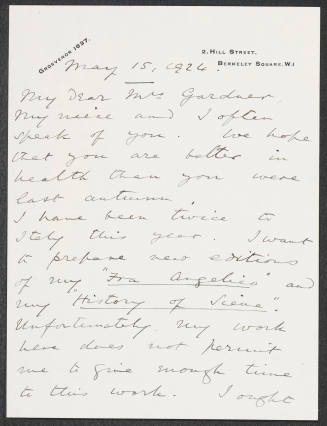

Lavenham, United Kingdom, 1864 - 1951, Fiesole, Italy