Frank Jewett Mather, Jr.

Deep River, Connecticut, 1868 - 1953, Princeton, New Jersey

Date born: 1868

Place Born: Deep River, CT

Date died: 1953

Place died: Princeton, NJ

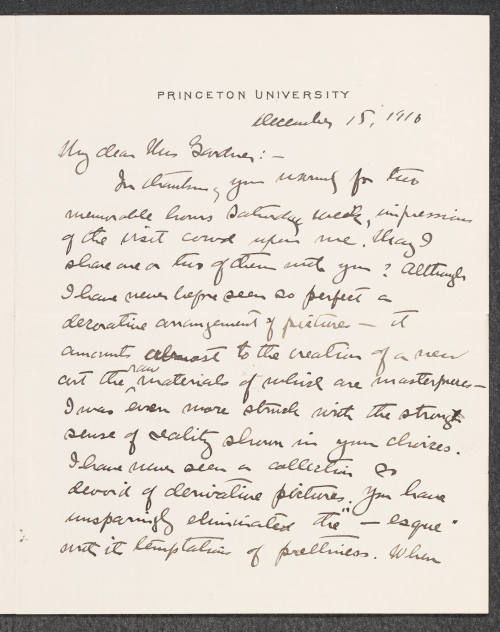

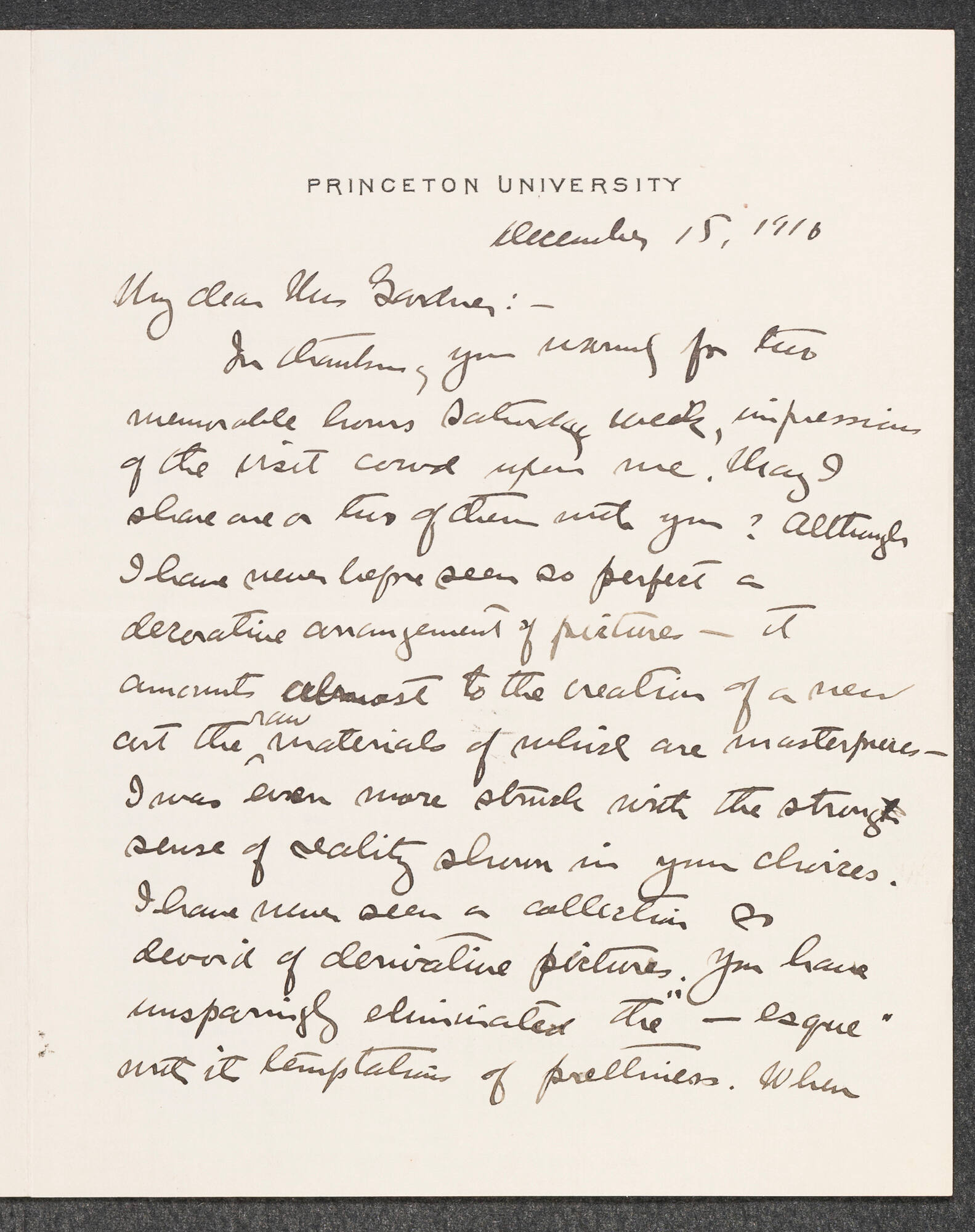

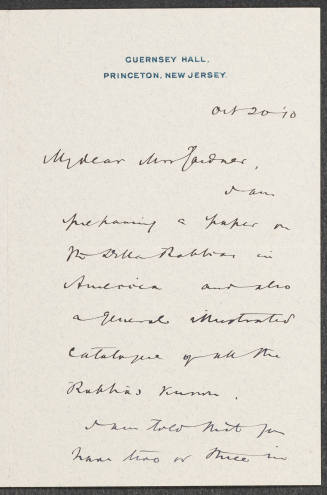

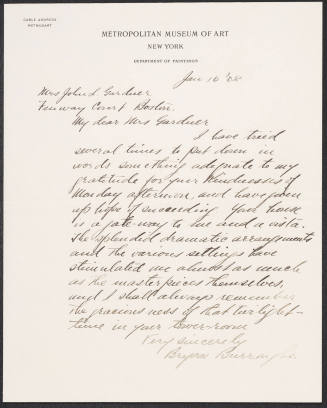

Second professor of the Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University, 1910-1933 and its first "modernist" (i.e., post-classicist). Mather was the son of Frank Jewett Mather, Sr. (1835-1929), a lawyer, and Caroline Arms Graves (Mather). After graduating in 1889 from Williams College, Williamstown, MA, Mather entered Johns Hopkins University where he completed his Ph.D. in 1892 in English philology and literature. That same year he traveled to Berlin to study art (specifically Italian painting) returning in 1893 to teach Anglo-Saxon and Romance languages at Williams. He mad a second trip to Europe, 1897-1898, studying at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes in Paris. In 1900 he spent a year in Paris returning in 1901 to accept a job as an assistant editor of the Nation and then as the editorials writer for the New York Evening Post. He spent part of 1903 in Spain where the painting of Velasquez particularly impressed him. In 1904 he began art criticism for the Post and assuming the American editor duties of the Burlington Magazine. He married Ellen Suydam Mills in 1905. Mather contracted typhoid fever the following year and, as part of the recovery, moved to Italy. He worked as a freelance journalist there covering among other events the Messina earthquake of 1908. Mather met the English-speaking expatriate community in there, including the art historians Bernard Berenson and Allan Marquand, founder (and major benefactor) of Princeton's the Department of Art and Archeology. Marquand, who was traveling in Italy at the time, invited Mather to teach art history at Princeton, which Mather did beginning in 1910. Mather became the first Marquand Professor of Art and Archaeology, once again writing art criticism for the Post. Mather's first book was the 1912 Homer Martin: Poet in Landscape on the relatively minor painter Homer Dodge Martin. His second, The Collectors, featured an early profile of Berenson. Mather recognized the Armory Show in 1913 to be the epoch event it was: his review of it in the Independent won him an honorary degree from Williams College the same year. His collected criticism and essays appeared as the book Estimates in Art in 1916. Mather continued to write scholarly articles on art until the United States entered World War I, when he served as an ensign in the naval reserve. In 1920 Mather joined the Smithsonian Art Commission, a group charged with advising the national art collections and assumed the editorship of Art in America. His survey of likenesses of the poet Dante, Portraits of Dante, appeared in 1921. In 1922, Mather was chosen to direct the Museum of Historic Art (now the Princeton University Museum of Art). He used the university's endowments and his own funds to build the core of the European and American painting collection In 1923 he issued his History of Italian Painting, a standard especially among the general reading public. When Marquand died in 1924, Mather took over editing of Marquand's books on the Robbia artists (published in 1928). That was followed by two books in 1927, one authored with fellow Princeton art Professor Charles Rufus Morey and the musicologist William James Henderson (1855-1937), The American Spirit in Art for The Pageant of America series, and Modern Painting, a curious book that valued the classical-tradition in painting of the nineteenth-century but little of the twentieth. He particularly disparaged German Expressionist painting. In 1931 Mather updated his Estimates collection with pieces on Albert Pinkham Ryder, Thomas Eakins, and Winslow Homer. He was among the first to rank these Americans higher than the Society painters (e.g., John Singer Sargent) which were contemporarily valued. A book on The Isaac Master was published in 1932. He retired emeritus from Princeton in 1933, retaining the directorship of the art museum. Mather wrote a treatise on esthetics, Concerning Beauty in 1935. Venetian Painters appeared in 1936. Western European Painting of the Renaissance in 1939. Mather attempted vainly to re-enlist in the navy for World War II (he was over seventy). In 1946 he retired from the Museum, donating his collection of prints and drawings to the collection. He was succeeded by Ernest DeWald. Mather retired to his Bucks County farm, known as "Three Brooks." He died in a Princeton hospital at age 85. His papers are housed at Princeton University.

Like many independently wealthy self-educated art historians of the early twentieth century, Mather was highly opinioned and at times quixotic. His art histories are seldom consulted today; his art criticism, however, was both influential in his own time and enduring. His criticism written in the Atlantic Monthly reached a wide audience. In 1963 the professional society for art historians, the College Art Association, named an annual award for American criticism in his honor. Mather's criticism seldom pandered to the crowd or even to museum practice. He ranks among the top builders of early academic art collections among American universities. As a museum director, he was against "period rooms" in museums, the practice of placing objects together in a total environmental consistent with the period in which the objects were produced. He criticized the 1924 American Wing opening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York for pandering to the "antiquarian sentimentality" as well as the larger size modern museums. Distinctly pro-French (or anti-German), perhaps because of the World War, he once wrote in a book introduction, "I shudder when I think what a German or a Germanized American scholar would have made of the subject . . .".

Home Country: United States

Sources: Wilson, Edmund. "Mr. Morey and the Mithraic Bull." in The Triple Thinkers: Twelve Essays on Literary Subjects: 8-12. Revised edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1948, pp. 3-14 (amusing sketch of Mather); [museum opinion] Tomkins, Calvin. Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1970, p. 201; Turner, A. Richard. "Mather, Frank Jewett." American National Biography; Lavin, Marilyn Aronberg. The Eye of the Tiger: the Founding and Development of the Department of Art and Archaeology, 1883-1923, Princeton University. Princeton, NJ: Department of Art and Archaeology and The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1983; Marquis, Alice Goldfarb. Alfred H. Barr, Jr.: Missionary for the Modern. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1989, p. 25; Morgan, H. Wayne. Keepers of Culture: The Art-Thought of Kenyon Cox, Royal Cortissoz and Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989, pp. 105-149; "Frank Jewett Mather Papers." Manuscripts Division Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library, http://libweb.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/mather/; [obituary:] "Dr. F. J. Mather, Jr., Art Scholar, Dead." New York Times November 12, 1953, p. 31.

Bibliography: [dissertation:] The Conditional Sentence in Anglo-Saxon. Johns Hopkins University, 1892; The Collectors: being Cases Mostly under the Ninth and Tenth Commandments. New York: H. Holt and Company, 1912; [review of Amory Show] "Newest Tendencies in Art." Independent (New York) March 6, 1913: 504-512; Estimates in Art. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1916; [anti-German remark] "Foreward." Clapp, Frederick M. Jacopo Carucci da Pontormo, his Life and Work. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1916, p. xi; edited, Art in America 10 ( Jan. 1920-); The Portraits of Dante Compared with the Measurement of his Skull and Reclassified. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1921; co-edited, Art Studies: Medieval, Renaissance and Modern1 (1923) - v. 8 (1931); A History of Italian Painting. New York: H. Holt and Company, 1923; and Morey, Charles Rufus, and Henderson, William James. The American Spirit in Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1927; Modern Painting: a Study of Tendencies. New York: H. Holt and Company, 1927; "Art and Authenticity." Atlantic Monthly 143 March 1929: 310-320; "Smaller and Better Museums: a Commentary and a Suggestion." Atlantic Monthly 144 ( December 1929): 768-773; Concerning Beauty. Princeton: Louis Clark Vanuxem Foundation/Princeton University Press, 1935; Venetian Painters. New York: H. Holt and Company, 1936; Western European Painting of the Renaissance. New York: Henry Holt, 1939.

https://dictionaryofarthistorians.org/matherf.htm accessed 10/20/2017

Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr. (6 July 1868-11 Nov. 1953), writer, art collector, and museum director, was born in Deep River, Connecticut, the son of Frank Jewett Mather, a lawyer, and Caroline Arms Graves. An 1889 graduate of Williams College, Mather received his Ph.D. in English philology and literature from Johns Hopkins University in 1892. As an undergraduate he had caught the chronic virus of art collecting, and by 1892 he had begun his studies of Italian painting. After a year of study in Berlin Mather returned to Williams to teach Anglo-Saxon and Romance languages from 1893 to 1900, taking a year off for study in Paris.

In 1901 Mather temporarily changed careers to become a journalist, in retrospect a happy move in that it allowed him to develop a prose style qualitatively rare among his peers. He served as assistant editor of the Nation, as editorial writer with the New York Evening Post, and as art critic for the latter paper in 1904-1906 and again in 1910-1911. That his interest in scholarship remained firm is suggested by his service as American editor of London's Burlington Magazine, in 1904-1906.

In the fall of 1903 Mather wrote his fiancée from Madrid that the Spanish painter Velasquez "trusted his eye, and he trusted life," a characterization as apt for Mather's own critical writing in these years. In 1905 he married Ellen Suydam Mills, with whom he had two children.

In 1906, in the wake of Mather having experienced serious illness, the Mather family moved to Italy. There Mather freelanced, becoming one of the first correspondents to cover the devastating Messina earthquake of 1908. It was probably in Italy that he met Allan Marquand, founder of the Department of Art and Archeology at Princeton University. Appealing to Mather's unabated interest in Italian art and his former enjoyment of academics, Marquand persuaded Mather to accept appointment at Princeton in 1910 as the first Marquand Professor of Art and Archaeology.

In 1912 Mather published two books that demonstrated his range as a thinker and a writer: Homer Martin, Poet in Landscape, an art historical study of the painter Homer Dodge Martin, and The Collectors, a collection of short stories, one of which contains a sketch of his friend Bernard Berenson. In March 1913 Mather published a brilliant review of the Armory Show in the Independent. Recognized as a distinguished commentator on culture, he was given an honorary degree by Williams College later that year.

Beyond a prolific production of scholarly articles on problems in European and American art, Mather wrote a number of books intended for the general reader, of which the History of Italian Painting (1923, 1938) is the best known, having served tourists and students alike for a quarter century. In 1927 he published Modern Painting, a book marked by both an essentially nineteenth-century respect for the classical tradition and an unease with what he saw as unbridled excesses of the modern imagination. Venetian Painters followed in 1936, and Western European Painting of the Renaissance in 1939.

In addition to broad surveys, Mather wrote specialized monographs (Portraits of Dante, 1921; The Isaac Master, 1932), a drama (Ulysses in Ithaca, 1926), a work on aesthetics (Concerning Beauty, 1935), and two sets of collected critical essays (Estimates in Art, 1916 and 1931). This last volume grew out of work on "The American Spirit in Art," a 1927 volume he co-authored with Charles Rufus Morey and William James Henderson in the series The Pageant of America. The 1931 Estimates arguably contains Mather's most prescient and enduring critical judgments, in elevating Albert Pinkham Ryder, Thomas Eakins, and Winslow Homer above the easier visions of John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler.

Although this production attests to the contemplative side of Mather, he was by temperament an activist. Late in life he recalled his service as an ensign in the naval reserve in World War I as among the most interesting years of his life. From there he went on to build a schooner, the Four Winds, and in World War II he tried unsuccessfully, at over age seventy, to re-enlist in the navy!

Indeed, Mather's career took an activist turn when in 1920 he began twenty-seven years of service on the Smithsonian Art Commission, a distinguished panel that advised on the development and disposition of the nation's art collections. Given Mather's decades of collecting (everything from first editions of Herman Melville to Japanese sword guards), Princeton turned to him in 1922 to direct its art museum, a post he held until 1946, thirteen years beyond his designation as professor emeritus. He established the core of the museum's holdings through institutional purchase and generous personal donations, primarily in old master European and American paintings and drawings. Always outspoken and no friend of the protocols of academic decorum, the tenure of "the Skipper" as director seems never to have been viewed as becalmed by his colleagues.

Mather's last working decades saw him in residence at his Bucks County farm, "Three Brooks," where he enjoyed, as he put it, "the mixed blessing of alfalfa, goats, and Japanese beetles." There he led the active and contemplative life, re-reading Cicero and reading Gide for the first time when not tending the goats.

Today, Mather's contributions seem to vary in importance. He was the dean of American art critics, highly influential in both artistic and literary circles, and the leading prize for art criticism in America today (awarded by the College Art Association) bears his name. On the other hand, his art historical writing is largely dated in both fact and judgment, though highly interesting as a document of the earlier years of art history in America. His role as a collector in the history of the American university and college museum is secure. At his death his qualities as a teacher, combining great breadth with memorable language, were recalled by former students, who referred to him as "a wise and humane spirit," and "a mind with range and velocity."

When asked in his last year if there were one more book he would like to write, he replied "The Memoirs of an Unplanned Life." Mather died in Princeton, New Jersey.

Bibliography

"A Private Life," a biography written by Mather's father, is at the Archives of Princeton University, as is correspondence between Mather and many other notable literary and artistic figures. Important documents are also at the Princeton University Department of Art and Archaeology Archives and the Archives of American Art in New York City. See also Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, The Eye of the Tiger: The Founding and Development of the Department of Art and Archaeology, 1883-1923, Princeton University (1983), and H. Wayne Morgan, Keepers of Culture: The Art-Thought of Kenyon Cox, Royal Cortissoz and Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. (1989). An obituary is in the New York Herald Tribune, 12 Nov. 1953.

A. Richard Turner

Back to the top

Citation:

A. Richard Turner. "Mather, Frank Jewett, Jr.";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00557.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Aug 05 2013 16:52:12 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Hyde Park, Massachusetts, 1869 - 1934, New York

Brooklyn, New York, 1848 - 1936, South Dennis, Massachusetts

Quakertown, Pennsylvania, 1852 - 1926, New York

Florence, 1856 - 1925, London