Kenyon Cox

Warren, Ohio, 1856 - 1919, New York

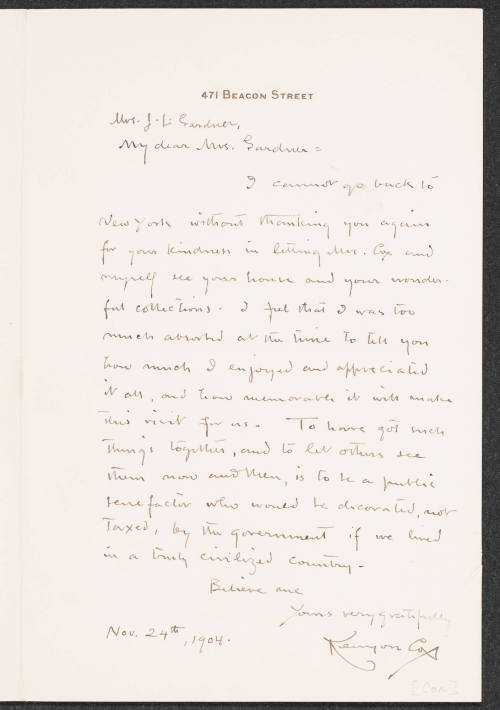

Cox returned to Ohio before he moved to New York City in the fall of 1883, determined to succeed in the nation's art capital. He immediately secured work as an illustrator for magazines, a common occupation among artists. Both dependable and talented, he pleased publishers and succeeded in making a modest name for himself among fellow artists, his illustrations appearing in influential magazines such as Century, Scribner's, and Harper's. He also instructed in life drawing, chiefly women's classes, at the Art Students League from 1884 to 1909; taught anatomy, some men's life drawing, and instructed individual painting students; and in 1885 wrote exhibition reviews for the New York Evening Post, some of which were reprinted in the Nation. He always expressed his views bluntly and was easier to respect than to like. His acerbic reviews antagonized a good many fellow painters, whose works he considered inferior. Cox quit writing these reviews in 1886 after receiving an important commission to make a series of figurative illustrations from grisaille paintings for a special edition of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's poem The Blessed Damozel. Although this work brought him considerable critical acclaim, he declined to illustrate other books because he wanted to focus on easel figure painting.

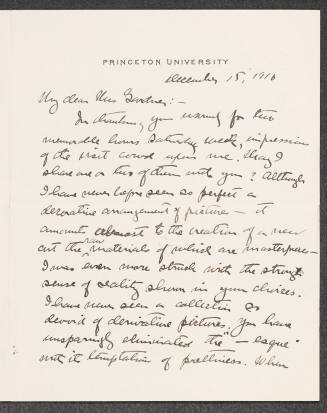

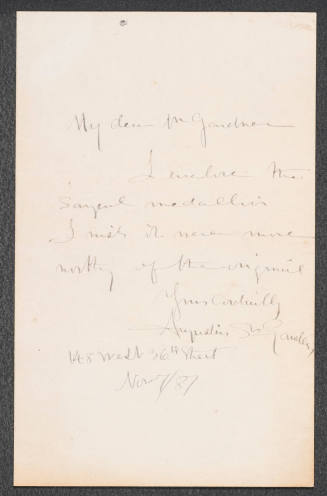

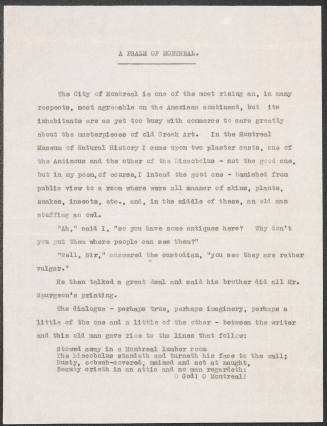

Cox did not think so, but he was an excellent landscapist and also produced quality portraits of friends, family, and fellow artists. His first love, however, was figure painting rooted in classical modes, whose unifying ideals he hoped to update for a modern society. In the mid-1880s he produced several large allegorical paintings in the tradition of European salons; these works gained him a reputation for breadth of thought and ability to paint but not a living. He continued to rely on illustration, teaching, and writing for a basic income. Cox wrote with great clarity and conciseness, whether in analyzing complex ideas and figures from art history or in surveying contemporary art writing, as in his book review essays for the Nation. By the end of the century he was a well-known cultural spokesman in genteel circles. The magazines that used his illustrations also published his criticism. Cox was always concerned with ideas and emotions in painting as well as its forms. He was a powerful spokesman for those aspects of painting and appreciation that both expanded the individual observer's mind and unified society while at the same time enhancing the artist's special vision. He was also a familiar figure in the affairs, and as a juryman, of art organizations such as the National Academy of Design and the Society of American Artists. He exhibited works at all the major exhibitions in the East and abroad in 1889 at the Paris Universal Exposition, where he received a bronze medal.

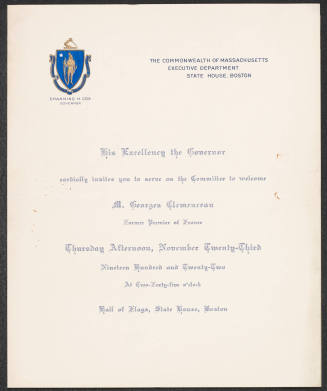

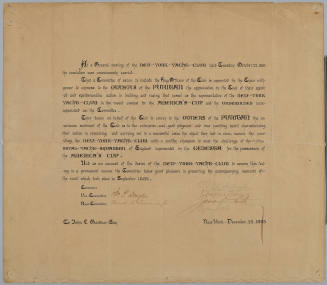

His ideas and artistic abilities, especially at figure paintings, made Cox important in the mural movement from the mid-1890s to the First World War. This period witnessed a flowering of arts, crafts, and architecture based on Italian Renaissance models. Architects received many commissions for public buildings, apartment houses, offices, and private dwellings suitable for mural decoration. This muralism encompassed several subjects and approaches: historical scenes, current events, abstract depiction of social forces, and classicism modeled on the Renaissance. Cox became a leader in this last approach, using a style of painting that attempted to make lofty ideals readily accessible to all kinds of viewers through easily read symbols, such as idealized female figures. Cox created large mural commissions for numerous buildings, including the Walker Art Gallery at Bowdoin College (1894), the Library of Congress (1896), and the state capitols of Minnesota (1904), Iowa (1906), and Wisconsin (1912-1915). He also produced designs for stained glass, statuary, and external stone decorations, such as those for the University Club in New York City and the Boston Public Library. He also produced classical designs for magazine covers, diplomas, and other documents as well as the back of the $100 federal reserve bank note of 1914.

Cox's reputation as a traditionalist made him a logical foe of the emerging trend toward modernism. Intensely devoted to art as thoughtful personal expression and as unifying cultural force, he could not be moderate about work he thought was purely personal or idiosyncratic, as most modernism seemed to be to him. His acerbic reviews of the historic Armory Show of 1913, and other widely read criticism, separated him from the coming generation, though he believed that his artistic and cultural ideals would triumph in the long run.

Cox had married Louise Howland King, whom he had instructed at the Art Students League, in 1892; the couple had two sons and a daughter. Although he may have been formidable in his public roles, Cox was an affectionate husband and father. He could even be whimsical as when he made special drawings of mythical animals to accompany nonsense verse for his children, published as Mixed Beasts (1904). The family spent most summers after the late 1890s in the artist colony in Cornish, New Hampshire. Mural commissions ceased with the coming of the world war in 1914, and Cox spent his last years in poor health and some emotional depression over modernism, which he could not understand or accept but whose momentary triumph he sensed. He died of tuberculosis at his apartment in New York City.

Bibliography

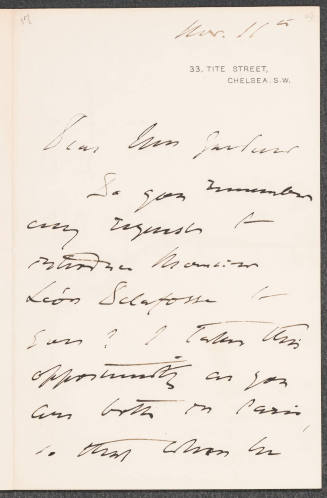

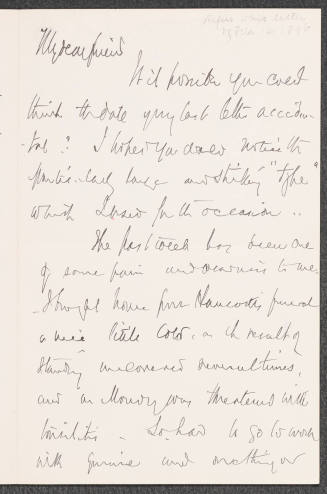

In the 1950s Cox's son, Allyn, who became a noted decorator, gathered his father's papers and disposed of his residual paintings and drawings. The papers formed the Kenyon Cox Collection at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. Material relating to Cox's mural commissions appears in several other collections, such as the Cass Gilbert Papers at the New-York Historical Society and the respective capitol commission records at the Minnesota Historical Society and the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Some other letters are in the holdings of the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and other collections. The Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York City is the chief repository of his residual drawings and designs. His paintings are in several major museums. Allyn Cox bequeathed other easel works, sketchbooks, and drawings to numerous regional museums. Cox's own major writings, though not his exhibition or book reviews, are collected in Old Masters and New (1905); Painters and Sculptors (1907); The Classic Point of View (1911), an elegant summary of his ideas; Artist and Public (1914); and Concerning Painting (1917). He is the subject of several works by H. Wayne Morgan: Keepers of Culture: The Art-Thought of Kenyon Cox, Royal Cortissoz and Frank Jewett Mather, Jr. (1989); two volumes of letters, An American Art Student in Paris: The Letters of Kenyon Cox 1877-1882 (1986) and An Artist of the American Renaissance: The Letters of Kenyon Cox 1883-1919 (1995); and a full biography, Kenyon Cox, 1856-1919: A Life in American Art (1994).

H. Wayne Morgan

Citation:

H. Wayne Morgan. "Cox, Kenyon";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00184.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:09:58 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Deep River, Connecticut, 1868 - 1953, Princeton, New Jersey

Dublin, 1848 - 1907, Cornish, New Hampshire

Rugby, England, 1887 - 1915, Skyros, Greece

Manchester, New Hampshire, 1879 - 1968, West Harwich, Massachusetts

Florence, 1856 - 1925, London