Bram Stoker

Dublin, 1847 - 1912, London

Despite his childhood infirmity, Stoker grew into a tall, handsome young man with a striking red beard and brown hair. He had a gift for oratory, an interest in acting, and was a champion athlete at Trinity College, Dublin, from which he graduated with a degree in science (1871) and a master's degree in pure mathematics (1874). Later, in 1890, he was called to the bar as a member of the Inner Temple, London, but never practised.

Stoker followed his father to Dublin Castle as a civil service clerk. Bored and restless, he volunteered as unpaid drama critic for the Daily Mail, and thus met Henry Irving, the first actor to be knighted. When Irving leased the Lyceum Theatre in London in 1878, Stoker joined him as business manager and remained by his side for twenty-seven years. Together they made the Lyceum the cultural heart of London.

An innovative administrator, Stoker was the first to number seats, to promote advance reservations, and to advertise an entire season rather than one play at a time. He supervised a staff of 128 employees, handled all Irving's correspondence, and organized the American and provincial tours. The Lyceum, the first company to tour with their own costumes and sets, made eight trips to the United States between 1883 and 1904.

Stoker had always wanted to be a literary man. His first prose, a novella entitled ‘The Primrose Path’, was published in The Shamrock in 1875. His first book, The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879), was written to codify the bureaucracy he was leaving. Before settling in London, on 4 December 1878 he married Florence Anne Lemon Balcombe (1858–1935), a Dublin beauty and the daughter of Lieutenant-Colonel James Balcombe of the 43rd regiment, who was also being courted by Oscar Wilde. They had one son, Noel, born in 1879. Despite long hours working for Irving, Stoker found the time between 1881 and 1895 to publish a book of fairy-tales called Under the Sunset (1882), a travel narrative entitled A Glimpse of America (1886), and three adventure-romance novels: The Snake's Pass (1891), The Watter's Mou (1895), and The Shoulder of Shasta (1895).

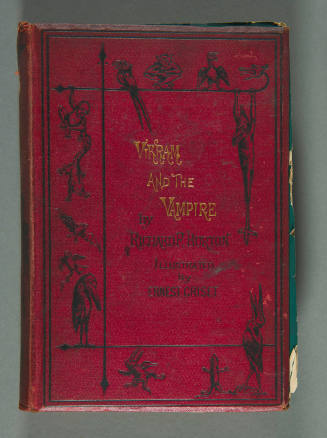

In 1890 Stoker began to make notes for a Gothic adventure story about Englishmen who safeguard their country by tracking down and killing a foreign invader, a Hungarian vampire. Complex and highly symbolic, the plot illustrated his fears about a world approaching a new century, about the unspeakable things which could happen to ordinary people, and about male insecurity and the dangers of subservience to another person. More Irish than Transylvanian, Count Dracula embodies the Celtic phenomenon known as ‘shape shifting’, the ability to become anything—a wolf, bat, rat, or swirling mist. Stoker was familiar with Irish folklore and with the early prose vampires: John Polidori's The Vampyre (1819), after a fragment by Lord Byron; Charles Robert Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer (1820); and James Malcolm Rymer's Varney the Vampyre (1847), a penny dreadful chronicling the adventures of an eighteenth-century aristocratic bloodsucker. Also influential was Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White (1860), a sensation novel employing Gothic elements, and, like Dracula, written in an epistolary form.

The major precursor of Dracula, as shown in the short story ‘Dracula's Guest’, which originally began the novel, was Carmilla (1872), a vampire-lesbian novel written by (Joseph) Sheridan Le Fanu, a fellow Irishman. Stoker's knowledge of eastern Europe was garnered from library research and conversations with his brother George, a medical officer who had served in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–8. During a holiday in Whitby, Stoker drafted the scene in which the count arrives in the fishing village on a ghost ship, and during other holidays at Cruden Bay in Aberdeenshire he walked daily to the ruined Slains Castle, considered the inspiration for Dracula's castle.

In his research Stoker had read about Vlad IV of Wallachia (1431–1476), known as Vlad Dracula or Vlad the Impaler, a tyrant who reputedly feasted al fresco amid rows of impaled bodies. The count takes his name from this historical figure but Henry Irving was the model for the vampire's physical characteristics and mesmerizing personality, in particular the desire to control. Stoker also wanted to create a dark, sinister role to swell the actor's repertory of villains, from Mathias to Macbeth to Mephistopheles. Dracula was a homage to Irving; however, Irving refused the part and the dramatic version was never performed in Stoker's lifetime. Originally titled The Un-Dead, the novel became Dracula shortly before publication in 1897. Favourably compared with Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights, and Edgar Allan Poe's The Fall of the House of Usher, it was considered weird and powerful, one of the best in the supernatural line, but no one examined its sexually unsettling themes until the 1970s. Dracula went through eleven editions during Stoker's lifetime, bringing in annual royalties but never the wealth he craved.

In 1931 Universal Pictures in Hollywood dressed Bela Lugosi in a white tie and opera cape for the film which spawned some 500 films worldwide. Where Stoker pictured a smelly, bloated predator hunted down in an epic adventure, film-makers saw a romantic-erotic myth. Through the years Count Dracula, the most filmed character in history after Sherlock Holmes, has grown younger, sensitive, and more handsome. Once film-makers had emphasized the connection between blood and sex, the Stokerian vampire achieved icon status.

Stoker wrote ten more books, including the supernatural novels The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), inspired by the Egyptian adventures of Oscar Wilde's father, which is credited with starting the mummy cult in films; The Lady of the Shroud (1909), one of whose characters is Lady Teuta, a make-believe vampire; and The Lair of the White Worm (1911), featuring Lady Arabella, a giant, primordial worm, made into a film in 1988 by Ken Russell in his fantasy style. But there is no character with the sustaining power of Count Dracula, or of Renfield, the zoophagous patient who eats flies and spiders, or of Dr Van Helsing, the heavily accented psychic detective.

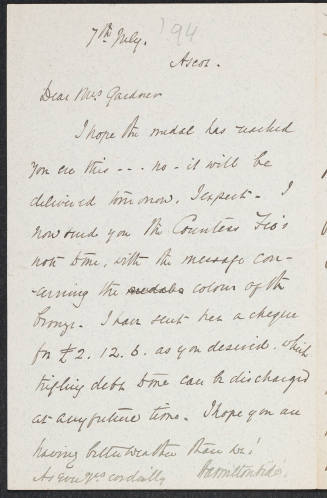

The Lyceum went into receivership in 1902 and Stoker never worked again in the theatre. His Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving (1906) forms a glowing two-volume tribute to his beloved friend. Following Irving's death in 1905, Stoker suffered a series of strokes and died from kidney failure on 20 April 1912 at his London home, 26 St George's Square, Pimlico; he was survived by his wife. His alleged syphilis has never been proven. He was cremated at Golders Green crematorium in Middlesex.

Each generation creates anew a liberating vampire, while scholars return to Stoker's novel hoping to learn more about the xenophobic and homophobic Victorians. A vampire in evening dress has usurped the red devil with pitchfork and pointed tail as the most popular symbol of evil. As writers, Stoker, Maturin, and Le Fanu constitute the Irish-Gothic triumvirate. The novel's enduring fascination stems also from Stoker's ambiguous ending. It is often assumed that Dracula was staked—so deeply imprinted is this violent film scene—rather than dying from multiple knife wounds. The power of the novel's ending inheres in the reader's ultimate uncertainty as to the permanence of Dracula's end.

Barbara Belford

Sources

B. Belford, Bram Stoker: a biography of the author of ‘Dracula’ (1996) · B. Stoker, Personal reminiscences of Henry Irving, 2 vols. (1906) · The essential Dracula, ed. L. Wolf (1993) · L. Irving, Henry Irving: the actor and his world [1951] · C. Frayling, Vampyres: Lord Byron to Count Dracula (1991) · P. Haining and P. Tremayne, The un-dead (1997) · D. Glover, Vampires, mummies, and liberals: Bram Stoker and the politics of popular fiction (1996) · DNB · d. cert.

Archives

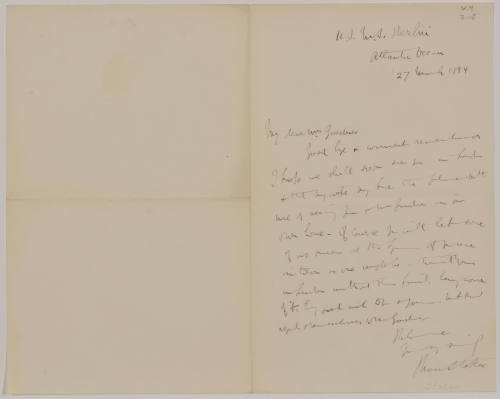

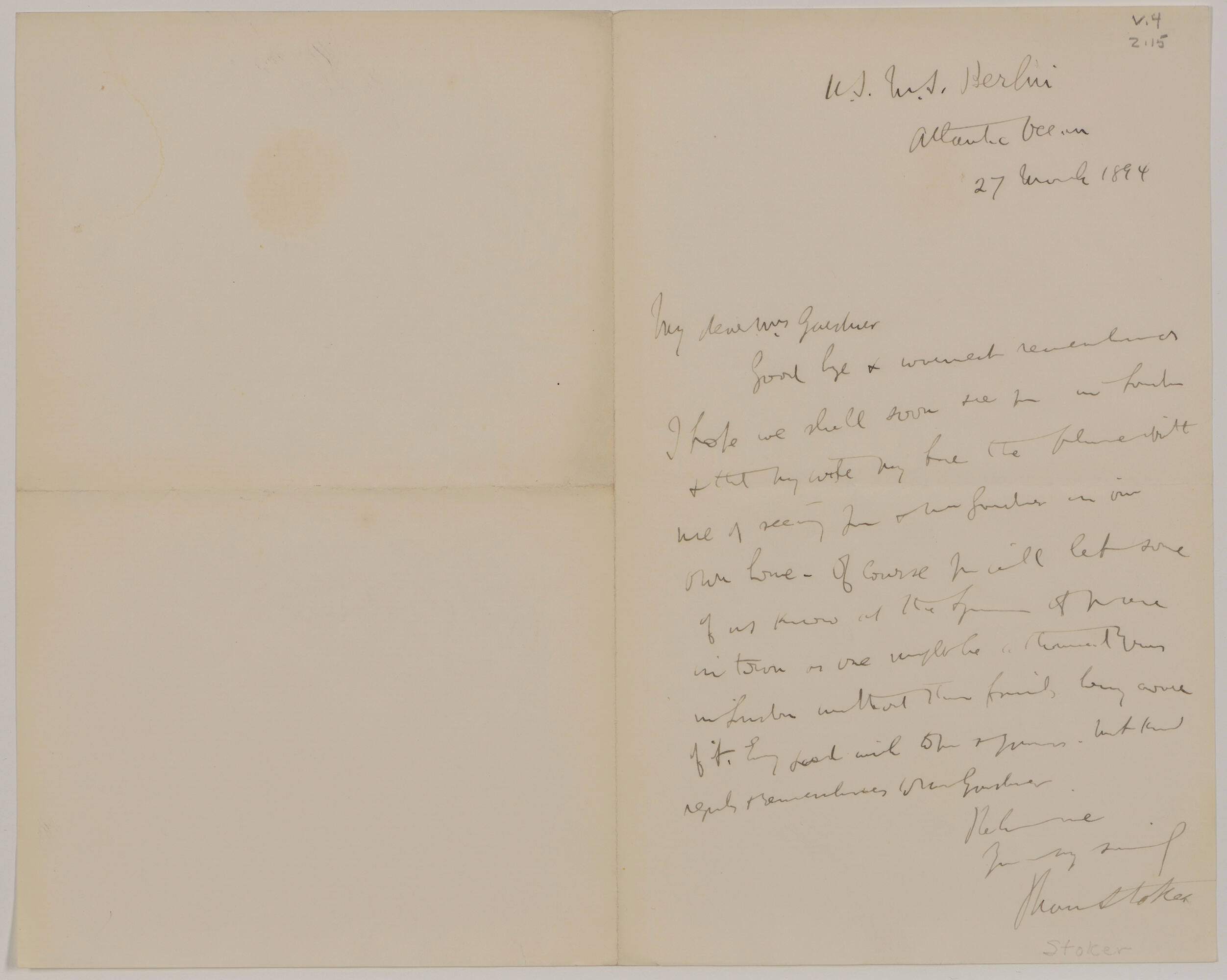

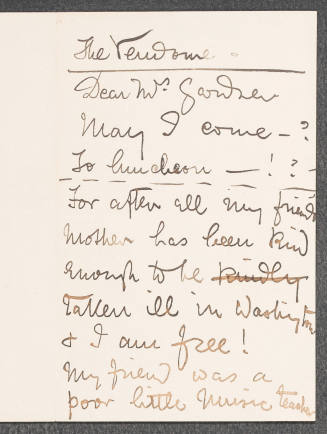

BL, letters · Bodl. Oxf., letters · NL Scot., letters · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., corresp. and literary MSS :: BL, Society of Authors archive · Ellen Terry Memorial Museum, Smallhythe, Kent, letters to Ellen Terry

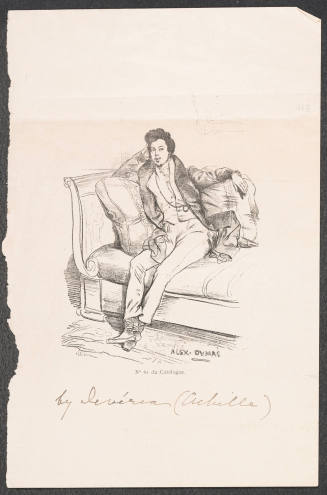

Likenesses

W. & D. Downey, photograph, 1906, NPG [see illus.] · G. Anderson, wall painting, 1911 (modelled for the panel William II building the Tower of London), Royal Exchange, London

Wealth at death

£5269 12s. 7d.: resworn probate, 15 May 1912, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Barbara Belford, ‘Stoker, Abraham (1847–1912)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38012, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Abraham Stoker (1847–1912): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38012

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Speldhurst, England, 1864 - 1950, Zurich Switzerland

Calcutta India, 1776 - 1847, London

Walsall, England, 1859 - 1927, Northampton, England

Villers-Cotterêts, France, 1802 - 1870, Dieppe, France

Keinton Mandeville, England, 1838 - 1905, Bradford, England

Paris, 1826 - 1906, London

Pierrepont, New York, 1859 - 1950, White Plains, New York

Torquay, Devon, England, 1821 - 1890, Trieste, Italy