Bernard Quaritch

active London, 1847 - 1899

LC name authority heading : Bernard Quaritch (Firm)

Buyer and seller of rare books and manuscripts since 1847; founded by Bernard Quaritch, 1819-1899; headquarters in London)

LC name authority rec. n 84093217

Quaritch, Bernard (British bookseller and publisher, 1819-1899)

German

Quaritch, Bernard Alexander Christian (1819–1899), bookseller and publisher, was born on 23 April 1819 at Worbis, a village in Thuringia, Germany. He was the eldest of five children of Karl Gottfried Bernhard Quaritsch (1795–1828), a man probably of Croatian extraction who was a fusilier in the Prussian army and a veteran of Waterloo, latterly an officer of justice at Worbis and Heiligenstadt, and his wife, Eleanore Henriette Amalie, née Rhan (1795–1875), the daughter of a Nordhausen merchant. Karl is said to have squandered his wife's fortune; he died at Heiligenstadt when Bernard was nine, and in 1831 the widow returned to Nordhausen, where Bernard completed his Gymnasium education, learning Greek, Latin, and French.

From the age of fifteen to nineteen Quaritch served an apprenticeship with a local bookseller, Koehne, and in 1839 set off for Berlin. There he found work at the publishing firm of Klemann, and in the bookshop of Adrien Oehmigke, mastering various bibliographical manuals, and acquainting himself with the English book world from literary and trade periodicals. Early in 1842 he moved to London, where he persuaded Henry George Bohn, the leading bookseller–publisher of his day, to hire him as cataloguer and general assistant. In 1844–5 he put in a year's stint with Théophile Barrois at Paris, crossing paths with the legendary bibliographer Jacques-Charles Brunet, but returned to London and Bohn for two final years of employment. In April 1847, announcing his ambition to be ‘the first bookseller in Europe’ (Quaritch), he set up on his own, with a capital of just £70 saved from his earnings, and an income eked out with piece-work for Marx and Engels as correspondent for their Neue Rheinische Zeitung—an improbable assignment, but one through which he briefly explored English politics, meeting Richard Cobden, Joseph Hume, and the rising bibliophile statesman W. E. Gladstone.

From 16 Castle Street, Leicester Square, London, Quaritch issued his first catalogue—a two-page, three-column ‘Cheap book circular’—in October 1847. His first season's sales amounted to no more than £168 10s., rising to £766 10s. in 1848, but hard work and tenacity rewarded him, and by 1855 his turnover was up nearly tenfold. His early specialities included literature, theology, law, mathematics, natural history and geography, music, fine arts, and architecture, from the outset distinguished by the linguistic scope of his stock. Catalogues 25 and 26, for instance (1851), listed books in no fewer than twenty-seven tongues, with particular emphasis on the oriental, which few English booksellers of the day could assess, let alone catalogue.

Most of Quaritch's early stock was, and remained, usefully ‘learned’—second-hand scholarly books at moderate prices—but the pursuit of fine, rare, and costly materials, for which he became famous, began in the mid-1850s, through connections with private collectors like Alexander, Lord Lindsay, later twenty-fifth earl of Crawford, who initially patronized him for the range of his academic wares. For Lindsay he purchased, in the 1858 Daly sale, a Gutenberg Bible for £595, characteristically exceeding his commission of £525 in his determination to vanquish his rival agents; but Lindsay cheerfully forgave him, and a pattern was established. Over the next forty years Quaritch increasingly dominated the salerooms in London, and often elsewhere, like no other bookseller in history: armed with generous commissions and auction-house credit (which he began to demand, when his non-participation could seriously depress auction results), and counting on rapid turnover, he bought substantially at every major sale from the late 1850s to his death, taking the lion's share of such glamorous dispersals as Perkins (1873), Tite (1874), Didot (1878–9), Sunderland (1881–3), Beckford-Hamilton (1882–4), Syston Park (1884), Osterley Park (1885), Gaisford (1890), Salva-Heredia (1892–3), Ashburnham (1897–8), and William Morris (1898). On several occasions his bids accounted for nearly half the results, though it must be remembered that he sometimes shared purchases with colleagues like Morgand and Techener of Paris and F. S. Ellis of London, and participated, like most of his contemporaries, in post-sale ‘settlements’. Commissions from a host of institutions and private collectors also swelled his figures, but in bidding for stock he set individual price records again and again, famously paying £3900 for the Gutenberg Bible in the Syston Park sale (breaking the single-lot benchmark which had stood since 1812) and £4950, four days later, for a 1459 Mainz psalter printed on vellum. By then he had earned his nickname in the press, the Napoleon of Booksellers—although he himself, perhaps with a thought for his father, held Bonaparte ‘in horror and contempt’ for ‘his extreme selfishness and his cruelty’ and ‘possess[ed] no books or objects concerning him’ (letter to Miss Kett of Bedford, 28 Jan 1893, priv. coll.).

Quaritch's ever-expanding inventory was housed in London, successively, in shops at 61 Great Russell Street (a false start in 1847), 16 Castle Street (1847–60, retained until 1909 as a warehouse), and 15 Piccadilly (1860–1907, premises reaching back to Vine Street). Although visitors were many and welcome, especially in Piccadilly, the principal method of distribution was by posted catalogues, and for these Quaritch soon became known all over the world. The earliest broadsheets gave way to octavo pamphlets (disguised between 1855 and 1864 as a low-postal-rate periodical, The Museum), then plump miscellaneous and specialist catalogues, and finally the massive ‘General catalogues’ of 1874 (with supplement, 1877), 1880, and 1887–8 (with index and supplements, 1892–7). The double-decker of 1874–7 contained 44,324 entries, representing about 200,000 volumes, while the 1880 catalogue ran to 2395 pages, measured over 6 inches thick, and weighed nearly 10 pounds—deliberately surpassing in bulk the 5 inch ‘guinea pig’ of Quaritch's old master Bohn (1841), and even Bohn's ‘enlarged’ catalogue of 1847–67, upon which Quaritch himself had once laboured. The final ‘General catalogue’, long esteemed as a bibliographical reference, extends to seventeen grand volumes, but of course the books listed in such compendia were not always available: the point of Quaritch's enterprise was to set guideline prices for standard copies of antiquarian and out-of-print books, appropriate to his policy in re-purchasing them, and to his customers' expectations.

Side by side with his more than 400 numbered and unnumbered catalogues (1848–86), Quaritch issued between 1867 and 1899 nearly 200 ‘rough lists’, aimed at clearing new purchases—often from recent named auctions—rapidly; he also revived the practice of marketing directly at auction himself, by trade sales at home and abroad of rare books and general stock, including his own publications, and remainders with new ‘Quaritch’ imprints. The last involved him in 1879 in a dispute with the United States customs authorities, whom he addressed in an aggressively autobiographical essay, A Letter to General Starring (1880); America did not back down, but Quaritch's trade-sale venues at one time spanned the globe from Australasia to Japan, Shanghai to Singapore to Calcutta, Amoy (Xiamen), and Rangoon, Cape Town to Leipzig, Dublin to Valparaíso.

As a publisher and distributor of books and periodicals, and agent for learned societies, Quaritch at first followed his forte in orientalia, with grammars and dictionaries in Turkish, Arabic, Persian, and Chinese. From 1854 onwards he concentrated almost exclusively on unpopular but meritorious scholarly works, preferring to buy titles outright from their authors, who would have been hard put to find an alternative; and although his manner in negotiating was peremptory, he took genuine interest in the projects he backed, and regarded ‘his’ writers as feathers in his own cap. He encouraged bibliographers like Charles Sayle, F. C. Bigmore, and C. W. H. Wyman (who prefaced their Bibliography of Printing (1880) with a portrait of Quaritch), J. G. Gray, and H. Buxton Forman, and sponsored W. C. Hazlitt's multi-volume Collections and Notes on English popular literature, as well as the standard Works of William Blake, edited by E. J. Ellis and W. B. Yeats (3 vols., 1893), translations by his friends Sir Richard Burton (The Lusiads, 1880–81) and Gladstone's cousin Lord Lyttelton (Translations from the Greek, 1861), and numerous facsimiles and reprints. His most celebrated publication was Edward FitzGerald's Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam, the first four editions of which (1859, 1868, 1872, and 1879) name Quaritch as publisher, although FitzGerald himself paid for the printing of the earlier two. The history of the rediscovery of the poem in a Castle Street remainder tray, and its subsequent celebrity, is well known, but the later, unedifying struggle over copyright between Quaritch and FitzGerald's estate casts Quaritch himself in a harsh light. His dispute with William Morris, however, whose Kelmscott Press books he contracted to subsidize and distribute in 1890, found him, if anything, the abused party.

In later life Quaritch was as proud of his clientele as his stock, boasting personal acquaintance with Disraeli and Gladstone, John Ruskin, William Morris, Edward FitzGerald, Sir Richard Burton, Sir Henry Irving, and Ellen Terry, as well as most of the noble and wealthy British collectors of the day. Although he never visited America, he represented and corresponded extensively with New York's James Lenox (falling out with him over a conflict at auction with Lord Crawford) and New England's briefly meteoric William Gibbons Medlicott (1816–1883), whose cause he adopted with uncustomary fervour in 1866. Institutional librarians at home and abroad flocked to his saleroom banner, notably Bodley's E. W. B. Nicolson, Cambridge University's Henry Bradshaw, Harvard's Justin Windsor, and George Bullen and Edward Maunde Thompson of the British Museum, whose agent Quaritch became on the retirement of F. S. Ellis in 1885; while from Athens John Gennadius showered Quaritch with commissions (1885–91), and, in New Zealand, Alexander H. Turnbull began his intensive collecting career with offers and parcels from Quaritch. Literary and press recognition, which Quaritch relished and courted, came in periodical notices, interviews, episodes in Richard Jefferies' Amaryllis at the Fair (1887) and C. J. Wills's three-decker novel of 1891, John Squire's Secret, and in recollections by A. C. Swinburne, W. C. Hazlitt, and Oliver Wendell Holmes. Many books and booklets bear Quaritch's own name as compiler or author, but most were largely ghost-written, like the useful Dictionary of Book-Collectors (1892) and various tracts and ‘opuscula’ of the Sette of Odd Volumes, a dining-club he co-founded in 1878.

Bernard Quaritch married, in 1863 or 1864, Charlotte (Helen) Rimes (1831/2–1899), with whom he had three children: Charlotte, Gertrude Annie, and Bernard Alfred (1871–1913), who succeeded his father as head of the bookselling firm. Quaritch died of bronchial pneumonia at his home, 34 Belsize Grove, London, on 17 December 1899, in his eighty-first year; he was buried in Highgate cemetery. Physically and mentally he was a powerful man, short but wiry and barrel-chested, irrepressibly forthright, and given to bluff sardonic humour, but convivial and loyal, with a streak of unabashed sentimentality towards friends, and a patriotic devotion to his adopted country. His influence upon the international book trade in his fifty-year career can hardly be overestimated, and he was perhaps the last individual bookseller to unite under one roof major stocks of scholarly and rare works in virtually all fields of knowledge and imagination. In that achievement he was ably seconded by an intelligent staff, long led by the mercurial, multilingual, and polymath Irishman Michael Kerney (c.1832–1901), who joined Quaritch in 1857 and spent forty years as his chief assistant, ‘literary adviser’, and éminence grise. In later years Kerney was joined by Frederic S. Ferguson (1878–1967), the bibliographer whose speciality of early English literature helped to ensure Quaritch's pre-eminence in that field, and Edmund H. Dring (1864–1928), who, with his son Edmund (1906–1990), directed the firm in the century after Quaritch's death, and between them served it for 113 years. The shop moved from Piccadilly to 11 Grafton Street in 1907, and ‘Bernard Quaritch’ became a private limited company in 1917, remaining in the Quaritch family until 1971. Under new proprietorship, and after one more removal—to Lower John Street, Golden Square, in 1970—it continued into the twenty-first century.

Arthur Freeman

Sources

C. Q. Wrentmore, foreword, in A catalogue of books and manuscripts issued to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the firm, Bernard Quaritch Ltd (1947), v–xvii · A. Brauer, ‘Bernard Quaritch 125 Jahre’, Börsenblatt für den Deutschen Buchhandel (27 Feb 1973), A64–A67 · A. Brauer, ‘Der bedeutendste Antiquariatsbuchhändler des 19. Jahrhunderts und seine Familie’, Archiv für Sippenforschung, 52 (1973), 262–85 · B. Quaritch, Bernard Quaritch's letter to General Starring (1880) · N. Barker, Bibliotheca Lindesiana (1978) · N. Barker, ‘Bernard Quaritch’, Book Collector (1997), 3–34 [special number for the 150th anniversary of Bernard Quaritch] · F. Herrmann, Sotheby's: portrait of an auction house (1980) · A. Freeman and J. I. Freeman, Anatomy of an auction (1990) · A. Freeman, ‘Bernard Quaritch and “My Omar”: the struggle for FitzGerald Rubáiyát’, Book Collector (1997), 60–75 [special number for the 150th anniversay of Bernard Quaritch] · N. Kelvin, ‘Bernard Quaritch and William Morris’, Book Collector (1997), 118–33 [special number for the 150th anniversay of Bernard Quaritch] · E. M. Dring, ‘Michael Kerney’, Book Collector (1997), 160–66 [special number for the 150th anniversary of Bernard Quaritch] · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1900) · obit. [B. A. Quaritch — son]

Archives

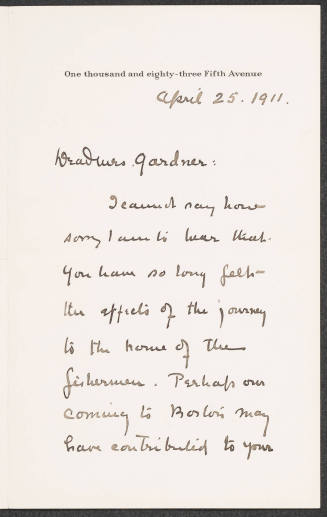

Bernard Quaritch Ltd, London, company archives · Bodl. Oxf., corresp. and papers :: Auckland Public Library, letters to Sir George Grey · BL, corresp. with W. E. Gladstone, Add. MSS 44389–44524, passim · Bodl. Oxf., bills and letters to Sir Thomas Phillipps · NHM, letters to members of the Sowerby family · University of Toronto, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, corresp. with Lord Amherst of Hackney

Likenesses

photograph, c.1849, repro. in Barker, ‘Bernard Quaritch’ · J. Mayall, photograph, c.1880, repro. in A catalogue of books and manuscripts, Bernard Quaritch Ltd · photograph, 1899, repro. in A catalogue of books and manuscripts, Bernard Quaritch Ltd · J. Brown, engraving (after photograph by J. Mayall), BM; repro. in Barker, ‘Bernard Quaritch’ · J. Brown, stipple, BM · oils (after photograph by J. Mayall), Bernard Quaritch Ltd, London · photograph, Bernard Quaritch Ltd, London [see illus.]

Wealth at death

£38,782 4s.: probate, 23 Feb 1900, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Arthur Freeman, ‘Quaritch, Bernard Alexander Christian (1819–1899)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22943, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Bernard Alexander Christian Quaritch (1819–1899): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22943

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated7/26/24

Southwater, England, 1675 - 1736, London

founded Edinburgh, 1795