Henry G. Bohn

London, 1796 - 1884, London

Biography:

Bohn, Henry George (1796–1884), translator and publisher, was born on 4 January 1796 and baptized in London on 7 February, the first of four sons of John Henry Martin Bohn (c.1757–1843), of Münster, Westphalia, Germany, and Elizabeth Watt, niece of James Watt, inventor of the steam engine; one of his brothers was the bookseller James Bohn. Bohn was educated at George III's expense, his father being the court bookseller. When he left school he joined his father's second-hand bookselling business. After a disagreement with him, he spent a short but successful period working in the City, before being persuaded to return to the family business. At an early age Bohn was entrusted by his father with the purchase of rare books. He travelled to the chief continental centres of the book trade and was one of the few bidders at a book fair at Leipzig on the day of the battle of Waterloo. While working for his father, he began his career as a translator, largely of German authors, although he was also fluent in French. His translations of Schiller and Humboldt afterwards appeared in his Foreign Classics series. He also gained experience of antiquarian books by cataloguing his father's acquisitions and by compiling a list of the library of Samuel Parr, which his father and J. Mawman published in 1827. Later, he assisted William Beckford and the duke of Hamilton in the acquisition of their libraries, being employed by the latter to compile a handlist of his collection.

Bohn, however, began to perceive that there was little hope of a partnership, and so, with the experience in his father's business behind him and a starting capital of £2000, he set up his own firm at 4 York Street, Covent Garden, London, in 1831, subsequently expanding to take over the neighbouring two houses. In the same year he married Elizabeth Lamb Simpkin (c.1802–1890), only child of the bookseller William Simpkin. They had three sons and one daughter.

His father let Bohn have some remainders at cost price and enabled him to buy stock on the continent before he started up on his own. In 1841, after ten further years of quiet progress, he astounded the book world with his guinea catalogue, so called because of its price. It cost Bohn upwards of £2000 to make and was famous not only for its size—it contained over 23,000 articles and, with a list of remainders 152 pages long, was the largest of its day—but also for its descriptions of the works for sale. It became a collector's item in its own right and made Bohn's reputation as a second-hand bookseller.

In 1843 Bohn's father died and his brother James went bankrupt. Family tensions developed, and, possibly unaware that his father had left instructions that his book stock was to be divided and sold at different auction houses, Bohn sought to dispose of the stock himself. His brothers disputed his right to do so and brought an injunction against him. The matter was resolved and James put back on his feet with the help of his brother John and three investors.

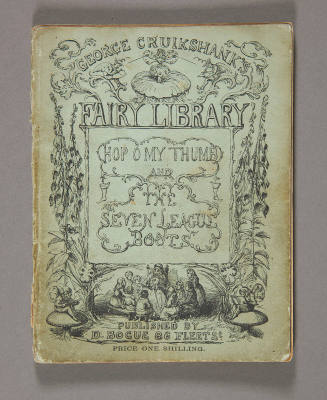

Shortly after this, Bohn turned to the remainder trade, reissuing dependable and instructive works in cheap formats. The stimulus for this was a dispute with David Bogue of Fleet Street who had published in his European Library series a life of Lorenzo de' Medici containing illustrations for which Bohn owned the copyright. Bohn brought an injunction against Bogue, and started a cheaper, rival series, his Standard Library. When Bogue went out of business, Bohn added the European Library to his own series. The Standard Library was soon followed by the Scientific and the Antiquarian (1847), Classical (1848), Illustrated (1849), Shilling (1850), Ecclesiastical (1851), Philological (1852), and British Classics (1853) series, together with further Collegiate, Historical, and Uniform series—over 600 volumes in all. The libraries represented one of the boldest and most successful experiments in publishing serious works at low prices—initially the Standard Library retailed at 3s. 6d. per volume, while later additions were priced at 5s. The libraries were successful largely because of Bohn's personal commitment to the project. He was a practical and shrewd man in business, an energetic worker, and tireless promoter of his libraries. He wrote, edited, translated, and indexed works he believed would enhance the series and selected the best of his remaindered copyrights for the purpose. The Gentleman's Magazine commented that these cheap editions ‘established the habit in middle-class life, of purchasing books instead of obtaining them from a library’ (GM, 5th ser., 257, 1884, 413), and Ralph Waldo Emerson said that Bohn had done ‘as much for literature as railroads have done for internal intercourse’ (Mumby, 400).

Bohn sold many of his works overseas and was all too aware of the problems of international copyright. On one occasion, Bohn's publication of Washington Irving's work, to which John Murray claimed the British rights, brought into public debate the issue of the protection of American copyright in Britain. His strong feelings on the issue led Bohn to publish a report of a public meeting held on 1 July 1851 on the question and he later claimed that he had been ‘a main instigator and abettor in overthrowing American and other foreign pretences of copyright in this country’ (Bohn, 6). Bohn was also an advocate of free trade in books and in 1852 campaigned as a member of the booksellers' committee against restrictions on their sale. The free traders won their point by the majority of a single vote and the Booksellers' Association was disbanded. Eight years later he objected to the abolition of paper duty, believing it would not lead to the fall of paper prices but to increased foreign competition in the manufacture and export of books to the colonial market. This time the political tide was against him and the paper duty was abolished.

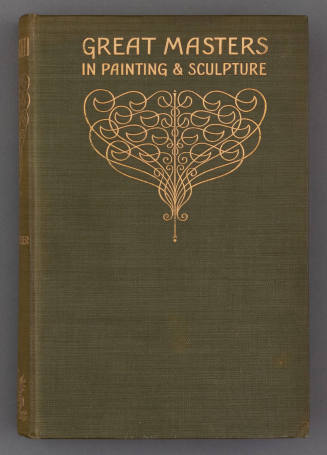

When it became evident that his sons did not wish to follow him into the business, Bohn decided to retire and sell his various enterprises. In 1864 he sold the stock, copyrights, and stereotypes of the libraries and some other works to Bell and Daldy for £40,000 and they moved into his York Street premises. They continued to publish the libraries, adding their own series including the Reference (1875), Novel (1876), Artists (1877), Economics (1881), Select (1888), and Sports and Games (1891) libraries. In 1921 the last new title was added to Bohn libraries. In January 1875 Bohn sold the remainder of his publishing business to Chatto and Windus for about £20,000.

Bohn withheld two favourite works from this deal: his Dictionary of Quotations (1867), into which he introduced a few verses from his own manuscript poems, and George Gordon's Pinetum (1875), to which he added an index and a list of plates from three earlier nineteenth-century botanical works. His friendship with the author encouraged him in his own enthusiasm for gardening at his home at North End House, Twickenham, Middlesex, which he had bought in 1850. His remarkable collection of conifers, rare shrubs, and roses was displayed in annual entertainments attended by Charles Dickens, George Cruikshank, and others, and his plants frequently figured in illustrated gardening journals.

After the sale of his publishing business Bohn catalogued his general second-hand stock which he kept in several Covent Garden warehouses, and secured temporary premises at his father's former business address in Henrietta Street. His contribution to bibliography resides largely in his enlargement and revision of W. T. Lowndes's Bibliographer's Manual (1864) carried out between 1857 and 1858, which is based on the knowledge he had gained through his acquisitions. The auction of Bohn's collection in 1872 contained many rare and valuable books including some volumes from the library of Horace Walpole. It raised above £13,500.

Many of Bohn's original works testify to his practical involvement in the projects he endorsed. For instance, he published a working plan to create a catalogue of the library of the British Museum, and played an important role in the Great Exhibition in 1851 and in the subsequent Crystal Palace Company. He also wrote for the Philobiblon Society on the progress of printing and contributed a Biography and Bibliography of Shakespeare (1864), drawing on his revised edition of Lowndes. Through his participation and regular attendance at meetings and debates, he played a valuable part in the life of the societies of which he was a member. These included the Society of Antiquaries, and the Royal Horticultural, Linnean, and the Royal Geographical societies.

One of the works Bohn contributed to his libraries was a guide to the collection of pottery, which grew out of his own interest in and knowledge of the subject. He had begun collecting seriously in the mid-1830s, accumulating a historical collection of rare and curious examples of pottery including some fifty pieces of so-called Lowestoft porcelain and earthenware, some bought from descendants of workers. Between 1875 and 1878 he sold this collection together with his china, porcelain, and ivories, raising nearly £25,000. After the sale, and with more room in his house, he turned his mind to pictures and in his eighties he compiled a catalogue raisonné. He revised the proof just before his death and his daughter, Elizabeth Munton, finalized the catalogue. Speculating on the size of her father's collections his daughter estimated he ‘must have bought about a dozen [pictures or virtu] a month for 50 consecutive years’ (The Times, 1 April 1885). The final part of his art collection was sold in March 1885 raising about a further £20,000. Bohn died on 22 August 1884 at his home, North End House.

Alexis Weedon

(“Bohn, Henry George (1796–1884),” Alexis Weedon in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, eee online ed., ed. Lawrence Goldman, Oxford: OUP, 2004, accessed September 2015. www.oxforddnb.com)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

British, 1864 - 1912

active London, 1800 - 1870

founded Edinburgh, 1795

Schleinitz, present day Unterkaka, 1816 - 1895, Leipzig