Image Not Available

for Harry Johnston

Harry Johnston

London, 1858 - 1927, near Worksop, England

Johnston, Sir Henry Hamilton [Harry] (1858–1927), explorer and colonial administrator, was born in London on 12 June 1858, the eldest of twelve children of John Brookes Johnston, secretary of the Royal Exchange Assurance Company, and his second wife, Esther Laetitia, daughter of Robert Hamilton, merchant. His parents belonged to the Catholic Apostolic (Irvingite) Church, and they educated their children very largely from home, and in an unusually intelligent and liberal way. At the age of ten Johnston had a year away from school to develop his precocious talents, drawing and painting at the Lambeth School of Art and studying animals and birds at the London Zoological Gardens. From 1870 to 1875 he attended the Stockwell grammar school and in 1876 studied French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese at evening classes at King's College, London. In the same year he entered the Royal Academy Schools to study painting. He made long painting expeditions, to Spain in 1876 and France in 1878, and in 1879–80 spent eight months in Tunis, painting and contributing illustrated articles to The Globe and The Graphic. He reported on the preparations for a French take-over of the country and visited eastern Algeria to observe the build-up of French military forces along the frontier. He later claimed that it was in Tunis, in 1880, that he resolved to devote himself to the extension of the British empire in Africa.

In 1882–3 Johnston accompanied a geographical and sporting expedition to Angola, serving as artist, naturalist, and Portuguese interpreter. The party travelled slowly from Mossamedes to the upper Cunene, where Johnston left it, making his own way to the Congo estuary. There he was befriended by H. M. Stanley, who was then establishing the Congo Independent State for Leopold II of the Belgians. With Stanley's help, Johnston ascended the river as far as Bolobo, and spent some weeks collecting plants, birds, and insects, and vocabularies of the local Bantu languages. Back in England, he published an attractively written and illustrated account of his journey, which established his reputation as an African explorer and led to his appointment by the Royal Society to conduct an expedition to study the flora and fauna of Mount Kilimanjaro in 1884.

Preparations for the Kilimanjaro expedition brought Johnston into contact with officials of the Foreign Office, whom he alerted to the commercially exclusive treaties being negotiated by Stanley with the chiefs of the Lower Congo, and also to the purchase of slaves, ostensibly to free them, for road building, porterage, and military service. At Zanzibar, Johnston was welcomed by the powerful consul-general, John Kirk, who made what arrangements were possible for his safety in the interior. However, it was to the Foreign Office rather than to Kirk that Johnston, a few weeks after his arrival, sent an absurdly optimistic proposal to turn his naturalist's camp near Moshi into the nucleus of a British colony of agricultural settlers to be chosen by himself, who would not need any government, nor by implication any defence, for many years to come. Arriving in London just at the moment when Germany was unveiling far-reaching colonial claims in Africa, Johnston's proposal was approved by the colonial committee of the cabinet, and was stopped only by the personal intervention of Gladstone. On his return to England, however, ‘Kilimanjaro Johnston’ was lionized and rewarded with the offer of a double vice-consulship in the recently gazetted British Protectorate of the Oil Rivers, in the south-east of modern Nigeria, and in the adjacent German protectorate of the Cameroons.

Johnston spent two and a half years in west Africa, during which he travelled widely in the hinterland of Old Calabar and the Cross River explaining the implications of British protection to peoples of whom most had no previous contact with the outside world. During the intervals between these journeys he studied the current partition of Africa and speculated about the interior frontiers which were still to be drawn. He embodied his thoughts in a series of dispatches, well illustrated by maps, which attracted the attention of Lord Salisbury, who, on Johnston's return to England, invited him to Hatfield, and kept him in London for almost a year as an informal adviser. Johnston's publication of The River Congo (1884) and The Kilimanjaro Expedition (1885) confirmed his reputation as an authority on Africa.

In 1888 and 1889 Salisbury was revising his policy on African partition in the light of his desire to retain control of Egypt, and therefore to encourage France in her west African ambitions, while increasing British claims in the east and the south. The new direction was epitomized in Johnston's slogan ‘From the Cape to Cairo’, and his own role in it was as consul in Mozambique, a post from which it was secretly intended that he should organize and direct the making of treaties with African chiefs in the region between Mozambique and Angola, where the Portuguese were known to be preparing to make treaties themselves. The main problem was that Salisbury depended for his parliamentary majority on the support of Liberal Unionists who opposed expenditure on imperial expansion. The plan became suddenly more viable when Johnston, on the eve of his departure, happened to meet Cecil Rhodes, who immediately offered to pay the expenses of Johnston's treaty making, if the areas so acquired could be assigned to the sphere of his British South Africa Company. The arrangement was sanctioned by Salisbury for the area that was to become Northern Rhodesia, but, in the area which was to become Nyasaland, where British missionaries were already established, he insisted on retaining control.

From July 1889 until March 1890 Johnston was engaged in this treaty making, travelling up the Zambezi and the Shire to Lake Nyasa and on to Lake Tanganyika, while a locally engaged assistant, Alfred Sharpe, took a more westerly route towards Katanga and Lake Mweru. In May Johnston was in Kimberley for consultations with Rhodes. He then returned to England for almost a year, while Salisbury negotiated boundary agreements with Germany and Portugal, and while arrangements were made for the administration of the newly acquired territories. In February 1891 Johnston was appointed commissioner and consul-general for the territories under British influence to the north of the Zambezi, while the British South Africa Company agreed to contribute £10,000 a year for three years towards the cost of administration. With this subsidy he recruited an armed force of seventy Sikhs from the Punjab and eighty Zanzibaris from the east coast, with whom he sailed up the Zambezi in July 1891 to begin the occupation of 400,000 square miles of central Africa, populated by some 2–3 million people.

Given such meagre resources, Johnston had to concentrate his efforts on the imperial protectorate rather than the company's sphere, and within that on a small area in the Shire highlands between Blantyre and Zomba, where a Church of Scotland mission had been operating since 1875, and where a small number of European planters were already established. Northwards, around and beyond Lake Nyasa, Yao and Ngoni, Bemba and Swahili were raiding weaker peoples for ivory and slaves, and building up their own strength in imported firearms. Johnston's early attempts to control the Yao round the southern shore of Lake Nyasa resulted in the loss of one of his two military officers and one fifth of his armed force, and put his finances so far into deficit that he had to go to Rhodes for more money. At last, in 1894, the new Liberal government of Lord Rosebery rescued him with a grant-in-aid, and the effective occupation of the northern two-thirds of the protectorate could begin. In 1895 Johnston visited India to recruit more soldiers, and during the next eighteen months he took a personal lead in deploying his troops in one district after another of the centre and the north, marching in the middle of the column under a white umbrella that was never lowered. Operations culminated in the destruction of the Swahili settlements in the far north which had defied all attempts at peaceful incorporation.

The Treasury grant led to the separation of the protectorate from the company's sphere and the end of personal relations between Johnston and Rhodes. It enabled Johnston to develop the idea of a system of ‘protectorate government’, based on the education of the black man rather than his economic exploitation by the white. Traditional societies should be disturbed as little as possible. Modernization would develop around the centres of colonial government, to which progressively minded Africans could move to join the modern economy. His ideas aroused much interest in England, but unfortunately he was unable to realize them in Nyasaland. The telegram from Salisbury congratulating him on his military victories and on the appointment as KCB found Johnston prostrate with his third attack of blackwater fever. It was clear that he would have to take extensive sick leave, and seek his next post outside the tropics.

Aged thirty-seven, and the youngest member of any of the orders of knighthood, Johnston seemed set to climb yet higher, but it was not to be. After waiting for more than a year, he accepted the consulate-general at Tunis and used it as a retreat from which to pursue his literary and scientific interests. At last, in 1899, there came the tempting offer to go for two years as special commissioner to Uganda, to establish civilian administration there after seven years of disastrous and very expensive military rule. It seemed a chance to climb back on to the ladder of high preferment, and his performance, though eccentric, was highly successful. Eight months out of eighteen were spent on the march, as much in the cause of science as of good government. At Entebbe, as earlier at Zomba, government house was overrun with wildlife, from snakes to crested cranes, from monkeys to a baby elephant. Johnston had the vision of a fertile country of peasant farmers, capable of producing tax revenues necessary to support a light form of colonial overrule as soon as the completion of the Uganda Railway should give them the means of exporting their produce. He concluded an agreement with the ruling chiefs of Buganda which made them privileged allies of the British, thereby enabling him to halve the military expenditure incurred by his predecessors. At the end of his tour of duty, Johnston got a GCMG, and his book The Uganda Protectorate was published in 1901, following British Central Africa in 1897, but he got no further offers of employment under the crown.

For Johnston, during his middle years, nothing seemed to go right. In 1896 he had married the Hon. Winifred Mary Irby, daughter of Florance George Henry Irby, fifth Baron Boston, and stepdaughter of Percy Anderson, head of the Africa department of the Foreign Office. In 1902 she was delivered prematurely of twin boys, who both died within hours; there were no more children. In 1903 and in 1906 he stood unsuccessfully for parliament—his small stature and rather high-pitched, squeaky voice made him a poor platform speaker. From 1904 until 1909 he was associated with two companies interested in the development of Liberia, both of which failed.

In 1906 the Johnstons moved from London to Poling, near Arundel. Here he engaged in ceaseless literary activity, much of it ephemeral. His longest-lasting books were the early ones, describing his own explorations on the Congo and Kilimanjaro. The large works which he published during his official service, on British Central Africa and on the Uganda Protectorate, were too encyclopaedic to be of lasting value, as were his later works on Liberia and King Leopold's Congo, the latter based on the papers of George Grenfell. His History of the Colonisation of Africa by Alien Races (1899) deserves respect as the first attempt at a history of the entire continent and remained without a rival until the 1950s. The best monument to his scholarship, however, was without doubt his Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages (2 vols., 1919–21), which set out the equivalents of some 250 words in 300 languages and dialects, for many of which he had himself collected the primary data. His classificatory analysis and historical interpretation of the evidence, though now outdated, were remarkable for the time. His natural history collections, which he sent to Kew, the British Museum, and the London Zoo, are more difficult to trace in detail, but his name is attached to many species and genera new to science at the time, notably the giraffe-like okapi of the Ituri Forest and the montane variety of the shrub senecio. In 1902 the University of Cambridge awarded him an Honorary Doctorate of Science, principally for his contributions to ornithology.

Johnston was for most of his life a social Darwinist, deeply dyed in racism, who talked about ‘savages’ and wrote comic verses about cannibals. However, his outlook was much changed by a journey to the United States and the Caribbean in 1908–9, when he met many distinguished people of African descent. In The Negro in the New World (1910) and in many of his later publications he stressed the importance of treating individuals as equal, regardless of their race. An agnostic in religion, he praised the work of Christian missionaries, whom he regarded as worthy agents in the evolutionary process. In 1923 he published his Story of my Life. In 1925 he suffered two strokes, which left him partly paralysed. He died on 31 July 1927 at Woodsetts House, near Worksop, and was buried at Poling.

Roland Oliver

Sources

R. Oliver, Sir Harry Johnston and the scramble for Africa (1957) · A. Johnston, The life and letters of Sir Harry Johnston [1929] · Burke, Peerage · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1927) · Gladstone, Diaries

Archives

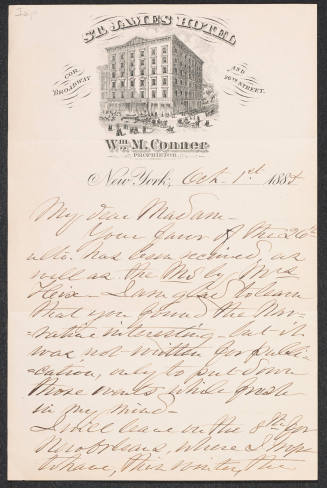

CUL, notes on African languages · National Archives of Zimbabwe, Harare, corresp. and papers · NRA, priv. coll., corresp. and papers · RGS, travel journal · SOAS, papers relating to Bantu language :: BLPES, corresp. with E. D. Morel · Bodl. RH, Cawston MS · Bodl. RH, letters to R. T. Coryndon · Bodl. RH, corresp. with Lord Lugard · Bodl. RH, Rhodes MS · CAC Cam., letters to W. T. Stead · Christ Church Oxf., Salisbury MS · National Archives of Zimbabwe, Harare, British South Africa Company MS · RGS, letters to Sir J. S. Keltie · SOAS, letters to Sir William Mackinnon · TNA: PRO, Foreign Office archives · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Sir Edmund Gosse · U. Newcastle, Robinson L., letters to Frederic Whyte

Likenesses

T. B. Wirgman, pencil drawing, 1894, NPG · H. Pegram, bust, 1904 · H. Furniss, pen-and-ink caricature, NPG · J. Russell & Sons, photograph, NPG [see illus.]

Wealth at death

£8047 7s. 11d.: probate, 5 Oct 1927, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Roland Oliver, ‘Johnston, Sir Henry Hamilton (1858–1927)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/34211, accessed 19 Oct 2017]

Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston (1858–1927): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34211

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, 1818 - 1893, New Orleans, Louisiana

at sea off the Cape of Good Hope, 1848 - 1914, London

Brighton, 1867 - 1962, Kew

Giessen, Hesse-Durmstadt, 1854 - 1925, Sturry Court, Kent