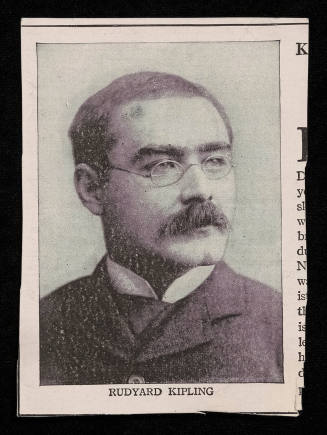

Henry M. Stanley

Denbigh, Wales, 1841 - 1904, London

wikipedia, accessed 8/29/2017

Sir Henry Morton Stanley GCB (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American journalist and explorer who was famous for his exploration of central Africa and his search for missionary and explorer David Livingstone.

Oxford DNB, accessed 8/29/2017

Stanley, Sir Henry Morton (1841–1904), explorer and journalist, was born on 28 January 1841 at Denbigh, where he was baptized as John Rowlands, the illegitimate son of John Rowlands (c.1815–1854), a farmer, and Elizabeth Parry (1822–1886), daughter of Moses Parry (d. 1846), a butcher and grazier. Of his putative father little is known. His mother was to have four more children before she married. Stanley spent most of his early years in the care of his grandfather Moses. Following his grandfather's death in June 1846, he was boarded out in a neighbouring cottage near Denbigh Castle. In February 1847 his mother's family halted the payments for his upkeep, and with no one else being willing or able to support him, he was taken to the workhouse at St Asaph. There he remained until May 1856, subject to the rigours of a poor law education.

Early years

Most of Stanley's schooling took place in the workhouse, where he read the Bible and the religious literature provided. He learned basic geography, arithmetic, and drawing, as well as doing some gardening, tailoring, and woodwork. Yet his memories of the workhouse, as narrated in his posthumously published Autobiography (1909), are overwhelmingly negative. His modern biographers have drawn attention to its more obviously fictional elements, including a dramatic account of his supposed ‘escape’ from the institution after years of abuse. Although the details of this story may be unreliable, its significance for the moulding of Stanley's character and future life is unmistakable. The autobiography gives full rein to the bitterness he felt at his early abandonment to the workhouse system, the remedy of a ‘dull-witted nation’ (p. 11). Stanley's shame about his illegitimacy, and resentment at his treatment as a child, fuelled an intense feeling of isolation, together with an overpowering ambition to prove his worth to the world.

Having left the workhouse in May 1856, aged fifteen, Stanley was employed by his cousin, Moses Owen, as a pupil teacher at the national school in Brynford, where he learned mathematics, Latin, and English grammar. He subsequently worked for Moses' mother, Mary Owen, who kept a farm and inn near Tremeirchion. In August 1858 he travelled to Liverpool, to stay with another aunt, Maria, and her husband Thomas Morris. Unable to secure a hoped-for job as a clerk, he worked as an assistant in a haberdasher's shop and as a butcher's boy. In December 1858 he took a position as a cabin-boy on an American packet ship, the Windermere. Once on board it became clear that he was to be employed as a deck hand, and after a laborious journey of seven weeks he jumped ship at New Orleans. Soon after his arrival he was befriended by a cotton trader named Henry Hope Stanley, for whom he worked for about a year. Henry Hope Stanley, though born in Stockport, had emigrated to the United States in 1836, and had established a substantial trading business along the Mississippi River. He effectively adopted the young John Rowlands, encouraging him to further his education and providing him with a responsible job on his plantation at Arcola. Thereafter, the man who had been baptized John Rowlands adopted the name Henry Stanley as his own, though he seems to have tried out several versions of his middle name (including Morelake and Moreland) before settling on Morton. Although Stanley records in his autobiography that his surrogate father died in Cuba in 1861, Henry Hope Stanley in fact lived until 1878. It seems the two men separated after an argument in 1860, after which the young Stanley was sent by his adopted father to work on a plantation in Arkansas. He did not last long there, however, and spent the next few months working in a trader's store at Cypress Bend.

In July 1861, two months after Arkansas had joined the Confederacy, Stanley volunteered for the ‘Dixie greys’. His motives are not exactly clear; indeed he was later to describe this act as a ‘grave blunder’ (Autobiography, 167). He served for nearly ten months, until the great battle of Shiloh, near the Tennessee River, in April 1862, during which he was taken prisoner. After being held as a prisoner of war at Camp Douglas, near Chicago, for six weeks, he secured his release by enlisting in the United States artillery. It was only through an attack of dysentery, which led to his being discharged, that he avoided fighting against his former allies. After further adventures, including a job on board an oyster schooner in Chesapeake Bay, he obtained work on a sailing ship bound for Britain. He arrived in Liverpool in November 1862, poor and dishevelled, and visited his mother, now married to the father of two of her children, at the village of Glascoed near Abergele. But his mother's reaction was far from welcoming, and (with the help of relatives of Henry Hope Stanley) he returned dejectedly to America. For the next year he was a sailor in the merchant navy, voyaging between Boston and the Mediterranean. He was employed for some time as a lawyer's clerk in New York. In July 1864 he joined the federal navy, entering the civil war for a third time. In December 1864 he saw action off Fort Fisher, North Carolina, during the bombardment of one of the last Confederate strongholds on the Atlantic. In February 1865 he apparently deserted the fleet at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and returned to New York.

Journalism and early travels

It seems that Stanley's first journalistic assignment was in June 1865, in St Louis, when the Missouri Democrat employed him on a freelance basis. He reported on his travels to the Rocky Mountains and California, and then to Colorado, where he took a variety of other jobs. There he teamed up with William Cook, another aspiring journalist, and together with Lewis Noe, a young shipmate who had served with him in the federal navy, they made plans for a journey through Turkey, central Asia and China. Travelling on a fruit ship, they arrived in Smyrna in western Turkey on 28 August 1866. After only two weeks of their journey, the three men found themselves embroiled in a violent encounter with local Turks, resulting in the rape of Noe. Narrowly escaping with his life, Stanley was eventually able to obtain the assistance of the American minister at Constantinople, who secured compensation for their treatment. On his way back to America, Stanley revisited his Welsh birthplace, where he dressed in a naval officer's uniform made up in Constantinople, claiming to be a civil war hero. As well as seeing his mother, Stanley paid a visit to the St Asaph workhouse, where the children were given a special tea in his honour.

Stanley's career as a journalist took a decisive turn in 1867. On his return to America he was taken on as a special correspondent by the Missouri Democrat, covering General Hancock's military expedition against the Cheyenne and the Sioux peoples in Kansas and Nebraska, and the subsequent peace conferences between General Sherman and the Plains Indians. (His dispatches during this period were reprinted in his Early Travels and Adventures in America and Asia, published in 1895.) Stanley's colourful reports established his growing reputation as a newspaper reporter, and having earned a modest sum from his writings, he decided to embark on a more adventurous mission. In December 1867 he persuaded James Gordon Bennett of the New York Herald to give him a commission as its special correspondent on the British expedition to Abyssinia. He left New York almost immediately, arriving in Suez in January 1868. Having joined Sir Robert Napier's forces at Annesley Bay, in the Horn of Africa, he marched with them for two months, witnessing the storming of Tewodros's fortress at Magdala. His sensational dispatches were the first to reach Europe, and he was soon employed on a permanent basis by the Herald. Over the next year, he sent reports on the construction of the Suez Canal, on an anti-Turkish uprising in Crete, and on the revolution against Queen Isabella in Spain. He visited his mother in north Wales in October 1868, and in the following March she accompanied him (with one of her daughters) on a trip to Paris.

How Stanley found Livingstone

The assignment which was to make Stanley famous, the ‘finding’ of David Livingstone, was the outcome of lengthy deliberations. In October 1868 James Gordon Bennett asked Stanley to go out to Africa to interview Livingstone, who had not been heard of for two years. Stanley travelled soon afterwards to Alexandria, and later Aden, where he spent two fruitless months waiting for news of Livingstone, occupying his time by reading and writing, and trying—in vain—to give up smoking. After a period of six months back in Spain, he returned to Paris, where he met Gordon Bennett in the Grand Hotel on 16 October 1869. The story of Gordon Bennett's renewed request to ‘find Livingstone’ was made famous by Stanley in his book How I Found Livingstone (1872). Eager to secure a return on his investment, Bennett instructed Stanley to report on his travels through central Asia to India, before proceeding to Zanzibar; had Livingstone been located in the meantime, it seems that Stanley might even have found himself on a mission to ‘find’ the Dalai Lama. In November 1869 Stanley was in Egypt for the opening of the Suez Canal. He later filed a series of colourful reports on his travels through Egypt, Palestine, Turkey, the Crimea, Georgia, and Persia, reaching Bombay in August 1870. He did not finally arrive in Zanzibar until 6 January 1871.

Hoping for a great scoop, Stanley prepared for his mission to find Livingstone in great secrecy, revealing the true purpose of his expedition only to the American consul. He gathered a well-armed party of nearly 200 men and set off from Bagamoyo on the African coast on 21 March 1871. David Livingstone was rumoured to be based somewhere near Lake Tanganyika, over 600 miles to the west. Although Stanley's route was familiar to Arab traders, within a week his party was encountering difficulties arising from the climate, the terrain, and disease, including malaria, dysentery and smallpox. Within three months he reached the trading post of Tabora (Unyanyembe), where he became embroiled in a war between the local Arabs and Mirambo, chief of the Nyamwezi. At Tabora, he acquired a servant, a young boy named Kalulu, whom he later brought to England. After a further three months he travelled towards the south-west, on the most arduous stage of his journey. Just over a month later (the exact date is uncertain) he was doffing his helmet to Dr Livingstone at Ujiji, on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, greeting him with the famous salutation, ‘Dr. Livingstone, I presume?’ (H. M. Stanley, How I Found Livingstone, 1872, chap. 11). Stanley brought Livingstone much-needed supplies and news, as well as a bottle of champagne which they shared on the day of his arrival. The two men spent four months together, for part of that time travelling on Lake Tanganyika, on remarkably friendly terms. But Livingstone politely refused to return with Stanley, preferring to continue his fruitless quest for the sources of the Nile. They parted at Tabora on 14 March 1872, Stanley reaching Zanzibar less than two months later. Stanley returned to London, by way of the Seychelles and Paris, where he handed over Livingstone's official dispatches to the British embassy. He landed at Dover on 1 August 1872.

On his return to Britain, Stanley found himself in a storm of controversy. ‘I am almost deafened with the hurly burly of strife’, he records in his journal; ‘every mail also brings proofs of English hate’ (H. M. Stanley, journal, 8 Aug 1872; copy at BL). His claims to have found Livingstone were ridiculed, the president of the Royal Geographical Society, Sir Henry Rawlinson, remarking that it must rather have been Livingstone who discovered Stanley. His descriptions of his travels at the geographical section of the British Association in Brighton were reported to have been described as ‘sensational stories’ by Francis Galton. His famous greeting at Ujiji was already being lampooned in the streets of London. And the growing rumours about his birth and parentage, which he attempted to suppress, were seized on by the press. Critics argued that Stanley lacked the credentials of either a gentleman or a scientist, and his claims to represent Livingstone particularly infuriated them. ‘The high-priests of geographical orthodoxy’, as Sidney Low describes them in the Dictionary of National Biography, did not emerge from this squabble with much honour. Equally, it must be acknowledged that Stanley's fiery temper and paranoid frame of mind did little to help his cause. Neither the subsequent reconciliation with the Royal Geographical Society, which awarded him its coveted gold medal, nor even an audience with Queen Victoria—who privately described him as ‘a determined ugly little man, with a strong American twang’—failed to heal the wound which the initial reception had caused. ‘All the actions of my life, and I may say all my thoughts, since 1872’, he wrote long afterwards, ‘have been strongly coloured by the storm of abuse and the wholly unjustifiable reports circulated about me then. So numerous were my enemies that my friends remained dumb’ (Autobiography, 289).

Stanley's book How I Found Livingstone, famously described by Florence Nightingale as ‘the very worst book on the very best subject I ever saw in my life’, was nevertheless a huge success. Shortly before its publication in November 1872, he left England for America, with his servant Kalulu, to undertake the first of many lecture tours. Soon after his return he published My Kalulu, a romantic adventure story for children set in central Africa. He spent much of 1873 reporting first on the civil strife in Spain and then on Wolseley's Asante campaign (where he was joined by several other correspondents, including G. A. Henty and Winwood Reade). On his way home from west Africa in February 1874 he learned of Livingstone's death at Ilala. He acted as one of the pallbearers at Livingstone's funeral in Westminster Abbey on 18 April 1874. Soon afterwards, with Edwin Arnold, editor of the Daily Telegraph, he devised a plan for a major trans-African expedition intended to solve the remaining mysteries of African geography; it was sponsored by the proprietors of the Daily Telegraph and the New York Herald. (Stanley was later to name mountains and lakes after all of his sponsors.) Before his departure, Stanley became secretly engaged to a young American woman, Alice Pike, and she seems to have been the inspiration for the naming of the portable boat he had constructed for the expedition, the Lady Alice. This was one of several unsuccessful liaisons with women before his marriage in 1890.

Trans-African expedition, 1874–1877

In August 1874, Stanley left London for Zanzibar. There he engaged over 300 porters, who were each to carry 60 pounds of goods, arms, and supplies, making it the largest African expedition ever seen. On 12 November the expedition left Zanzibar for the mainland, Stanley being accompanied by three young British volunteers, Francis and Edward Pocock, the sons of a Kentish sailor, and Frederick Barker, a clerk at the Langham Hotel in London (all three of his companions were to die in Africa). At this stage his hopes were concentrated on east Africa, as he aimed to settle conclusively the long-running controversies over its lakes and rivers. Travelling towards Lake Victoria, he soon became involved in violent encounters with local inhabitants which, together with the effects of disease, soon diminished the size of his party. From March 1875 the Lady Alice was used to circumnavigate Lake Victoria, during which Stanley met Mutesa, the powerful ruler of Uganda, whom he claimed to have converted to Christianity (and in so doing encouraged Christian missionaries to follow him into the region). At various places on the lake, notably Bumbiri Island, Stanley's party confronted the local population. Stanley's own reports of his violent ‘chastisement’ of the Bumbiri caused considerable controversy. During 1876 his party travelled on to the fringes of Lake Edward, and then, having met Mirambo, southwards to Lake Tanganyika. From there, they travelled west into the Lualaba basin and, in October 1876, Stanley had his first meeting with Hamid ibn Muhammad, the powerful Arab trader also known as Tippu Tib. After this meeting Stanley finally settled on a plan to follow the course of the Lualaba River to the north. From this point on, his expedition entered uncharted territory, travelling through the dense forests, fighting repeated battles, and negotiating the many perilous rapids on the Lualaba and Congo rivers. On 9 August 1877 what was left of Stanley's expedition reached Boma, having completed one of the most celebrated of all African expeditions of the nineteenth century.

The violence which accompanied Stanley's expedition gave rise to controversy in the British press. His attempts at self-justification for the punishment of the Bumbiri were challenged: ‘He has no concern with justice, no right to administer it; he comes with no sanction, no authority, no jurisdiction—nothing but explosive bullets and a copy of the Daily Telegraph’ (Saturday Review, 16 Feb 1878). His expedition was said by some to amount to exploration by warfare: ‘Exploration under these conditions is, in fact, exploration plus buccaneering, and though the map may be improved and enlarged by the process, the cause of civilisation is not a gainer thereby, but a loser’ (Pall Mall Gazette, 11 Feb 1878). John Kirk, the Zanzibar consul, launched a discreet enquiry in 1878, and concluded in a confidential report that ‘if the story of this expedition were known it would stand in the annals of African discovery unequalled for the reckless use of power that modern weapons placed in his hands over natives who never before heard a gun fired’ (1 May 1878, Foreign Office papers, TNA: PRO). But these misgivings were to be swamped by numerous tributes to Stanley's success in solving the remaining mysteries of African geography. On his return to Paris and London at the end of 1877, leading figures in geographical societies across Europe were lavish in their praise. In February 1878 he addressed the Royal Geographical Society twice, stubbornly defending his record against ‘soft, sentimental, sugar-and-honey, milk-and-water kind of talk’ (PRGS, 22, 1878, 145). His two-volume work Through the Dark Continent, published in June 1878, became another best-seller. Nevertheless, the controversy added to Stanley's disillusionment with the British government, which was lukewarm about his schemes to further the commercial penetration of the Congo region.

Opening up the Congo, 1879–1884

Stanley's association with the New York Herald came to an end in 1878, though not before its proprietor had apparently suggested that his next expedition should be to the north pole. His schemes for African commerce drew the attention of the Belgian king, Leopold II, who was captivated by the prospects of an African empire. Stanley met Leopold for the first time in Brussels on 10 June 1878, and by the end of the year (after a lecture tour in Britain) he had agreed to return to the Congo for five years in the service of the newly formed Comité d'Études du Haut-Congo (soon superseded by the Association Internationale du Congo). In August 1879 Stanley returned to the mouth of the Congo, intending to establish a series of permanent stations on the river. His work over the next five years was less that of an explorer than a road builder, earning him his famous nickname Bula Matari (‘breaker of rocks’). Stanley constructed his first station 110 miles inland on a hill at Vivi, which he likened to the acropolis. Then he supervised the building of a road to the second station at Isangila, 50 miles further north, which was reached in December 1880. In June 1881 he arrived at Stanley Pool, where another station called Leopoldville was established near Kinshassa. In September 1882, having suffered a severe bout of fever, he took leave in Europe, where he learned more of French claims on territory in the Congo basin then being advanced by the explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza. Returning to the Congo, he gained further territory for the association, on the lower Congo, and then travelled to Leopoldville, finding it in a chaotic state. He signed treaties securing large tracts of land around the upper Congo for the association, establishing stations as far as Stanley Falls, 1000 miles from the Atlantic coast, in December 1883. On 10 June 1884, Francis de Winton having succeeded him in his work for Leopold, Stanley began his journey home. Two months later he saw his mother in London for the last time.

Although it did not involve any significant geographical discoveries, Stanley considered his work on the Congo to be among the most important of his life. His book The Congo and the Founding of its Free State (2 vols., 1885) promoted what he called the ‘gospel of enterprise’ (2.377), emphasizing both the commercial potential of the region and the hard labour necessary to exploit it. He revelled in the name Bula Matari, portraying his aim in the Congo as nothing less than the conquest of nature. On his return, however, Stanley found himself a small player in a much larger game of international diplomacy, culminating in the Berlin Congress of 1884–5, at which he acted as an adviser to the American delegation. The establishment of the Congo Free State, a territory of nearly 1 million square miles which Stanley had done much to secure, was one of the most significant events in the history of the so-called ‘scramble for Africa’. Subsequent events were to show that Leopold's ambitions were not quite so philanthropic as Stanley represented them. But he denied to the last any responsibility for the atrocities that were to follow.

Following his return from the Congo in 1884, Stanley delivered addresses on the potential for commerce in central Africa to numerous commercial, anti-slavery, and geographical societies in Britain, hoping to raise funds for a railway along the lower Congo. In April 1885, he quietly visited America to become naturalized as an American citizen, apparently hoping to secure his rights as an author of works published there. In March 1886, after a prolonged illness, he made a continental tour, taking in Nice, Florence, Rome, and Naples. On his return to Britain he went on a cruise around the Scottish isles with Dorothy Tennant (his future wife) and her mother, as guests of the shipping magnate William Mackinnon.

The relief of Emin Pasha, 1886–1890

Shortly before Stanley left for a lecture tour of the United States in November 1886, Mackinnon suggested that he might lead another expedition to relieve Emin Pasha, the beleaguered governor of equatorial Sudan. On receiving a telegram from Mackinnon on 11 December 1886, Stanley interrupted his tour to return to Britain. Eduard Schnitzer, generally known as Emin Pasha, had appealed for help following the Mahdist uprising which engulfed General Gordon in 1885. Mackinnon, chairman of the British India Steam Navigation Company, led a campaign to raise funds for a relief expedition, with the support of various missionary, commercial, and geographical societies, as well as the Egyptian khedive. Although various alternative leaders were considered, including the explorer Joseph Thomson, Stanley was Mackinnon's choice.

From the many applicants to join the expedition, Stanley chose four men trained in the British army (Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot, Lieutenant William Stairs, Captain Robert Nelson, and Sergeant William Bonny), a one-time officer of the Congo state (John Rose Troup), and two gentlemen who donated £1000 each towards the expedition (Arthur Mounteney Jephson and James Jameson). These were subsequently joined by a doctor, Thomas Parke, and by another Congo adventurer, Herbert Ward. The expedition was heavily armed with Remington and Winchester rifles, a large quantity of ammunition, and the recently patented Maxim machine gun. On 21 January 1887 Stanley left London, travelling to Zanzibar by way of Cairo, where he met the khedive. At Zanzibar he negotiated an agreement with Tippu Tib, who was to accompany him round the Cape to the mouth of the Congo River. (This unlikely landing point for the expedition seems to have been chosen at Leopold's insistence, in order to further the interests of the Congo state.) After a difficult journey of a month, during which Stanley met Roger Casement, then in service on the Congo, the large party reached Leopoldville in April 1887. Here Stanley requisitioned three steamers, and the party continued in a flotilla up the Congo until its confluence with the Aruwimi River, where Stanley diverted to the village of Yambuya, to the east, which was reached on 15 June 1887. Here he decided to leave a rearguard, with instructions to wait until further supplies and reinforcements were received from Tippu Tib, while an advance party was to continue in search of Emin.

The advance party of just under 400 men, led by Stanley, set off for Lake Albert on a 450 mile journey of over five months through the Ituri rain forest. Stanley's descriptions of the tortuous passage through the dense forest rank among the most celebrated of all his writings. Ravaged by the effects of disease, hunger, and warfare, his party reached Lake Albert in December 1887. Failing to find Emin (who was at Wadelai), they retreated to Ibwiri, where a camp (known as Fort Bodo) was constructed. On 29 April 1888 Stanley himself finally met Emin Pasha, drinking champagne with him on the shores of Lake Albert, as he had with Livingstone at Ujiji in 1871. Unable to persuade Emin to leave immediately, he decided to return to find his rear column, leaving Jephson with Emin. In August 1888, at Banalya, just 90 miles from Yambuya, he found the rear column in a state of disarray. Barttelot had been shot dead, Troup invalided home, Ward and Jameson (who was himself dying of fever) were in search of further reinforcements, and the entire party had been decimated by disease and violence. The rear column had languished for thirteen months, waiting in vain both for the promised supplies from Tippu Tib and for news of the advance guard.

The rear column began the arduous journey on to Fort Bodo in August 1888, suffering further casualties on the way. On his arrival, in December 1888, Stanley learned that Emin had suffered the combined threat of a mutiny within his forces and renewed hostilities with the Mahdists. Emin's position appeared to be under threat, though he himself privately described Stanley's motives as ‘egoism under the guise of philanthropy’ (Tagebücher, 14 Jan 1889). After much cajoling, Stanley at last persuaded him to leave Equatoria, the party setting out from the shores of Lake Albert on 10 April 1889. They travelled near the Ruwenzori range, the fabled Mountains of the Moon, then through the lakes region, reaching the coast on 4 December 1889. By now, Stanley's relationship with Emin was at a low ebb, and he left Bagamoyo for Zanzibar without his prize. From there Stanley travelled to Cairo, where he spent two months writing his famous account of the expedition, In Darkest Africa (2 vols., 1890). He finally returned to London in April 1890. Honours and awards were showered on him by chambers of commerce and geographical societies throughout Europe, and he was awarded honorary degrees by the universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, and Edinburgh. A reception for him, organized by the Royal Geographical Society at the Albert Hall on 5 May 1890, was attended by 10,000 people, including the prince of Wales. Lecture tours followed, with Stanley speaking throughout Britain and America, where he travelled in a luxurious pullman car named Henry M. Stanley.

Although Stanley was widely acclaimed as a hero on his return to Britain, the Emin Pasha relief expedition was far from a success. From the start, as even Sidney Low's sympathetic portrait in the Dictionary of National Biography records, ‘it was hampered by divided aims and inconsistent purposes’. Others went further in their criticism, Sir William Harcourt describing it as one of those ‘filibustering expeditions in the mixed guise of commerce, religion, geography and imperialism, under which names any and every guise of atrocity is regarded as permissible’ (A. G. Gardiner, Life of Sir William Harcourt, 1923, 2.94). In addition to the ‘relief’ of the unwilling Pasha, Stanley had a number of other objectives, including the enhancement of the authority of both Leopold's Congo state in the west and Mackinnon's newly formed Imperial British East Africa Company in the east. More immediately, he had hoped to obtain Emin's valuable cache of ivory. His imperious manner alienated even the most loyal of his men, and several of the surviving members of the expedition and their relatives publicly contested Stanley's account of their ordeal. The strikingly bitter controversy over the fate of the rear column, especially after the publication of Barttelot's diaries in October 1890, raised questions not only about Stanley's leadership, but also about the wider purposes of the expedition. Leading figures in the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and Aborigines Protection Society charged him with using slaves as porters, and complained that the expedition had in fact opened up new routes for slave traders. These various challenges to Stanley's version of events were gleefully reported in the press, and resulted in numerous attacks, both sober and satirical, such as Henry Fox-Bourne's The other Side of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1891) and Francis Burnand's A New Light Thrown across the Keep it Quite Darkest Africa (1891). While Stanley had many influential supporters, the multiplication of different accounts of the expedition undermined his reputation just at the moment he had hoped it would finally be secured.

Final years, marriage, and death

On 12 July 1890 Stanley was married in Westminster Abbey to the artist Dorothy Tennant (1855–1926) [see under Tennant, Gertrude Barbara Rich], the second daughter of Charles Tennant, a landowner of Cadoxton, Glamorgan. They spent their honeymoon in Hampshire and then Switzerland and northern Italy, and soon after travelled together to the United States where Stanley conducted a lecture tour. In 1891 they left England for another demanding tour of Australia and New Zealand, returning in April 1892. A month later he was re-naturalized as a British citizen. Although there were attempts to persuade him to return to Africa, Stanley, with his wife's encouragement, decided to embark on a parliamentary career as a Liberal Unionist candidate for North Lambeth. Having been defeated in June 1892, he was elected in July 1895, spending the intervening years engaged in writing and at leisure. His five years as a member of parliament were undistinguished, and he frequently complained of the long hours and cumbersome procedures of the House of Commons. In October 1897, having received an invitation to attend the opening of the Bulawayo railway, Stanley travelled to South Africa. After visiting the Victoria Falls, he toured the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Natal, and at Pretoria he met President Kruger, whom he disliked intensely. He published an account of the journey in his book Through South Africa (1898). He was a strong supporter of the i

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Brentwood, England, 1858 - 1908, Sunninghill, England

London, 1858 - 1927, near Worksop, England

at sea off the Cape of Good Hope, 1848 - 1914, London

Torquay, Devon, England, 1821 - 1890, Trieste, Italy

Dexter, 1875 - 1967, Boston

Giessen, Hesse-Durmstadt, 1854 - 1925, Sturry Court, Kent

Edinburgh, 1860 - 1920, Cintra, Portugal