Pablo Casals

El Vendrell, Catalonia, Spain, 1876 - 1973, San Juan

Upon graduating, Casals went to Madrid with a recommendation from Isaac Albéniz to meet the Count of Morphy, a noted arts patron. Morphy secured Casals a pension from Queen María Cristina, whom Casals often visited. Morphy tutored Casals for two years, helping to finish his general education. Casals also studied chamber music with Jesús de Monasterio at the Royal Conservatory in Madrid. He pursued further musical study at Brussels Conservatory at Morphy's urging but the additional training proved unnecessary. Casals and his family then moved to Paris, but he found launching a career there impossible with his family in tow. He returned to Barcelona in early 1896 and became a cello teacher at the Municipal School of Music and first cellist in the Gran Teatro del Liceu. By 1897 he was touring in Spain with a chamber ensemble and as a soloist.

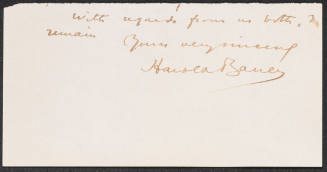

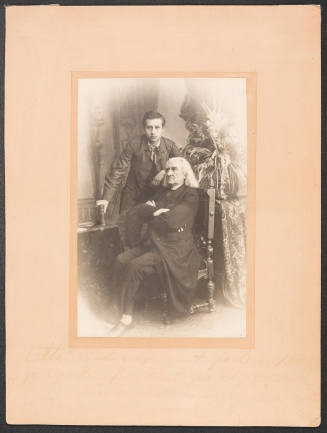

In May 1899 Casals moved to Paris alone, playing with the noted Lamoureux Orchestra and making his London debut. His extensive touring began in 1900. One of his first partners was pianist Harold Bauer, with whom he played often. For ten months in 1901-1902, Casals toured North America with other musicians. A serious injury to his left hand in San Francisco ended the tour for Casals, but by age thirty he had performed throughout Europe, Russia, and the Americas, often playing 150 to 200 concerts per year. He played at the White House for President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904. In 1906 he began playing in a trio with violinist Jacques Thibaud and pianist Alfred Cortot, forming a celebrated piano trio that performed together off and on until 1933. Casals often resided in Paris between 1906 and 1910, maintaining a relationship with Portuguese cellist Guilhermina Suggia (the couple lived together but never married).

Casals's relationship with Suggia ended in 1913, and in 1914 he married American soprano Susan Scott Metcalfe; they had no children. They were separated in 1928 and divorced in 1957. Like many European artists, Casals lived and toured in the United States during World War I. In 1919 he assisted Cortot in founding the École Normale de Musique in Paris and gave summer master classes there for a number of years.

After World War I Casals did not wish to continue such extensive touring and settled in Barcelona. In 1919 he founded the Orquestra Pau Casals, the first orchestra he conducted on a regular basis. The orchestra played seasons in the fall and spring until the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and reached out to the lower classes through the Workingmen's Concert Association, which grew to 300,000 members. During these years Casals continued touring in the United States, England, and elsewhere, using his earnings to support the orchestra. Late in the 1930s Casals made most of his important recordings as a cellist, especially those of J. S. Bach's Suites for Unaccompanied Cello (1936-1939) and Antonín Dvoák's Cello Concerto in B Minor (1939), recorded with the Czech Philharmonic conducted by George Szell.

Casals continued to live in Catalonia throughout the 1930s and during the Spanish Civil War but still toured. He shared his father's Republican political beliefs and was forced into exile at the end of the war. He became active in refugee relief efforts and spent World War II in Prades, a village in French Catalonia. His life became difficult after the German occupation of the town in late 1942. After France was freed, Casals performed numerous concerts in England and France, but by the end of 1946 he was disillusioned by the world's acceptance of the Franco government in Spain and withdrew from public performance. He was openly hostile toward musicians who had appeared to collaborate with fascist governments, most notably Cortot. Casals retired to Prades, where he began to compose again and teach cello. His companion in Prades was Franchisca Capdevila, a close friend and confidante for many years, who lived with Casals from 1928 until her death in 1955.

Casals's return to the concert stage was largely the work of violinist Alexander Schneider. Unable to lure Casals to the United States for concerts, he took the advice of Casals's lifelong friend, pianist Mieczyslaw Horszowski, and planned a Bach Festival in 1950 that brought many musicians to Prades. The festival included a chamber orchestra that Casals directed, many chamber music performances, and solo concerts by Casals. The early Prades Festivals were subsidized heavily by Columbia Records, which released many discs of the performances. The Prades Festivals helped reestablish Casals's position in the musical world. Although his greatest years as a cellist were behind him, his best work as a conductor was just beginning. Many performances that he directed were recorded, and sometimes they were filmed.

The last period in Casals's life began when an eighteen-year-old Puerto Rican cellist, Marta Montañez, arrived in Prades to study in late 1954. She rapidly moved from favorite student to secretary. After traveling together in Europe in the summer of 1955, in December Casals and Montañez sailed for Puerto Rico. Casals visited the family of his mother, a native Puerto Rican, and found the island a worthy substitute for his native Catalonia. Before he left Puerto Rico in March 1956, the first Festival Casals had been planned there for April 1957, again with the help of Schneider. Casals moved to Puerto Rico in 1957 and lived there the rest of his life. He suffered a heart attack on the eve of the first festival but fully recovered. Casals married Marta Montañez in 1957; they had no children. There is little doubt that the domestic happiness this brought Casals kept him a productive musician into extreme old age.

Casals spent the last sixteen years of his life working on the festivals he helped create and teaching a regular schedule of master classes. The Festival Casals in San Juan took place each spring and the Prades Festival each summer. Beginning in the early 1950s he taught in August at the Zermatt Summer Academy in Switzerland, and after 1960 he taught at the Marlboro Music Festival in Vermont in July. Eventually Marlboro replaced Prades on Casals's schedule; a number of his later recordings were made as a chamber musician and conductor at Marlboro.

Casals's reputation as a humanitarian stems from his refugee relief efforts in the years around World War II and his work for peace in the last two decades of his life. In 1958 he signed a letter with Albert Schweitzer that called for an end to atomic weapons testing, and later that year he participated in a United Nations Day concert broadcast throughout the world. In 1958 he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, and in November 1961 he performed in a highly publicized, televised concert at the John F. Kennedy White House. Beginning in 1960 he conducted his oratorio, El Pessebre (The manger), in a crusade for peace, leading the work thirty-three times in a number of countries before his death. He spent more time in Puerto Rico after 1966 but took part in dozens of performances after his ninetieth birthday, including his third concert at the United Nations in 1971 and his last visit to Israel in September 1973. Casals died in San Juan.

Casals's influence as a musician and teacher was monumental. He redefined cello technique, freeing players from unnecessarily confining practices in the right and left hands. He was among the first successful touring solo cellists, helping codify the cello's solo repertory and especially championing Bach's Suites for Unaccompanied Cello. He taught many important cellists and influenced most players of the instrument. He had an important career as a conductor in Spain before World War II and throughout the world late in his life. Although Casals was a fine pianist and fertile composer, few of his compositions were published during his lifetime. His musical taste as a performer and composer was profoundly conservative, but because of the integrity that he brought to his music making he transcended the conflict between traditional musical sounds and the avant-garde. A man of deep principles, Casals had many devoted friends both in and out of music, but his relationships were sometimes strained by his inability to compromise significantly. Few musicians have had the same impact as a humanitarian and spokesman for peace.

Bibliography

Collections of Casals's papers are at the Fundació Pau Casals in San Salvador, Spain, and in the personal possession of his widow, Marta Casals Istomin. Some of Casals's published interviews include J. Ma. Corredor, Conversations avec Casals (1955), later published in English as Conversations with Casals (1956); and Albert E. Kahn, Joys and Sorrows: His Own Story (1970), also published as Joys and Sorrows: Reflections (1974). Both of these works provide useful pictures of the musician, but Casals controlled the selection of material to be included. A major biography is H. L. Kirk, Pablo Casals (1974), written in the last years of Casals's life with his cooperation. Although mostly laudatory, the book nevertheless touches on most aspects of Casals's life, including those he hesitated to discuss in interviews. Other useful biographies include the brief but extensively illustrated Bernard Taper, Cellist in Exile: A Portrait of Pablo Casals (1962), and Robert Baldock, Pablo Casals (1992), a detailed and evenhanded study that provides a list of Casals's recordings available on compact disc. Enric Casals, Pau Casals: dades biogràfiques inèdites, cartes íntimes I records viscuts (1979), provides an intimate portrait written by his brother, who used unedited sources, letters, and descriptions of his relationships with many important musicians. An interesting photographic essay concerning Casals's music making and domestic life in the mid-1960s is Vytas Valaitis, Casals (1966), which includes text by Theodore Strongin. Casals's musical thoughts and personality are the subject of David Blum, Casals and the Art of Interpretation (1977), a study intended for the musically literate. Obituaries are in the New York Times, 24 Oct. 1973, and Time, 5 Nov. 1973.

Paul R. Laird

Citation:

Paul R. Laird. "Casals, Pablo";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-02133.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 13:24:26 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Florence, 1878 - 1959, New Rochelle, NY

New Malden, Kingston-upon-Thames, England, 1873 - 1951, Miami, Florida

Kharkov, Ukraine, 1863 - 1945, New York