Matthew Stewart Prichard

Somerset, 1865 - 1936, Buckinghamshire

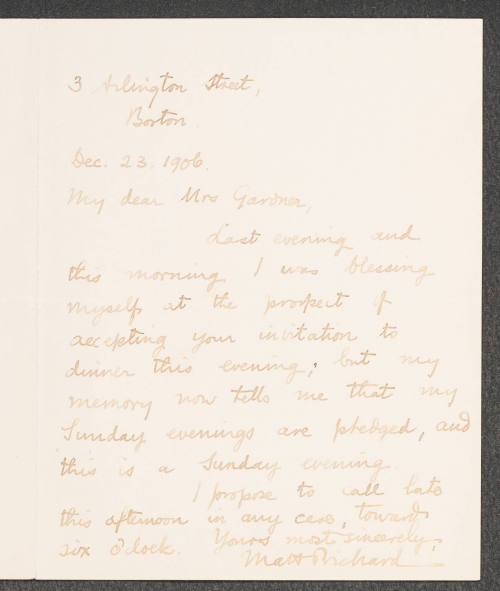

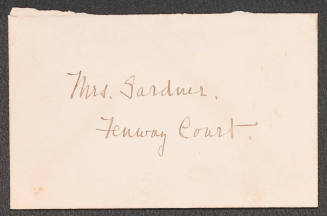

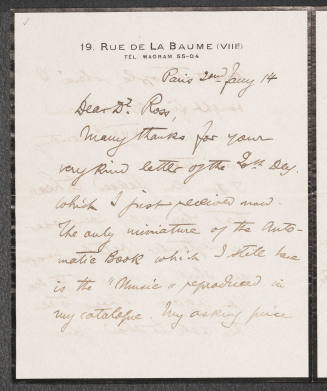

Dismissed in June 1907 because of conflicts among the trustees, Prichard travelled for a year in Italy, where he became fascinated by Byzantine art. Between December 1908 and June 1914 he lived in Paris: this was to be the most creative period of his life. Through Sarah and Michael Stein, he met Henri Matisse early in 1909. The connection which he enthusiastically drew between Matisse's art and the art of the Orient profoundly influenced the artist, who discovered Byzantine art through Prichard. Prichard was also a fervent admirer of Henri Bergson's philosophy, which he used as a basis for his revolutionary system of aesthetics, denying any value to the Western representational image and conventional ideas of beauty, and celebrating instead the power of decoration. This formed the core of the philosophy which ‘the mysterious and mystic Prichard’, as Isabella Stewart Gardner called him (Letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner, 381), taught to a circle of young Frenchmen, notably Georges Duthuit, the art critic (and Matisse's future son-in-law), and to some of his London acquaintances, such as Roger Fry and T. S. Eliot. Fry, who had first met Prichard in Boston in January 1905, had been impressed by his views about museums and oriental art; on 26 January 1911 he described him to Clive Bell as ‘a great friend of the Steins’ and ‘a great Bergsonite’, who would be able to show him ‘a good many things’ in Paris (Letters of Roger Fry, 1.339).

‘Art’, Prichard would say, ‘is formative, not informative’, adding that:

There are certain truths, those which transcend the power of the intellect to grasp, which can only be conveyed by evocation. That is the justification of Byzantine expression or of Matisse's. If the communication is spatial, superficial, something for the intelligence, then spatial terms, the concept, the vision of practical life, suffice for the conveyance, and there is no excuse for an evocative procedure. Reality is one of the truths which exceeds the power of the intelligence to grasp it, but appearance is a simple intellectual fact. (Prichard, notebooks, Paris, Bibliothèque Byzantine, Fonds Thomas Whittemore)

Travelling in Germany in August 1914 Prichard was interned as an English citizen in the prisoner-of-war camp of Ruhleben, where he organized the intellectual life of his fellow prisoners, among whom he ‘was perhaps the most remarkable character’ (Ketchum, 260). Liberated in 1918, he returned to London, worked briefly for the government committee on prisoners, and formed a new circle of disciples at the Gargoyle Club, including David Tennant and John Pope-Hennessy, who was ‘introduced to museology’ and became ‘familiar with Prichard's views’ from these ‘seminars on aesthetics held by him in the mornings, among shattered glasses, in the Gargoyle nightclub before the Red Studio of Matisse’ (Pope-Hennessy, 273–4).

In his last years Prichard's moods became increasingly unpredictable. He played a major, though unofficial, role in the writing and publication of the first and second preliminary reports on the rediscovery of Byzantine mosaics in Hagia Sofia, Constantinople, by the Bostonian Thomas Whittemore, one of his pupils (T. Whittemore, The Mosaics of Haghia Sophia at Istanbul, 1933 and 1936). He died suddenly, on 15 October 1936, of a coronary thrombosis, in his brother's house at Parslow's Hillock, Great Hampden, Buckinghamshire, and was cremated on 19 October. He never married. Prichard was a Socratic character: his writing mostly took the form of letters. Beyond a few early studies on the museum, his main publication, Greek and Byzantine Art (1921), is the text of a conference given at the Taylor Institution, Oxford, in 1919.

Rémi Labrusse

Sources

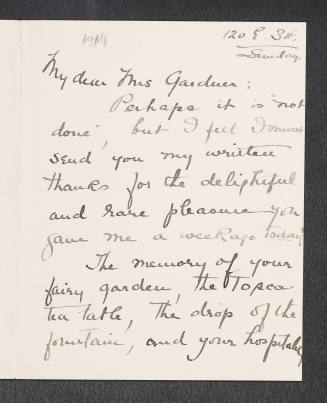

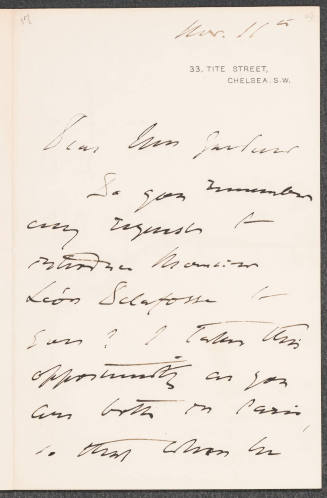

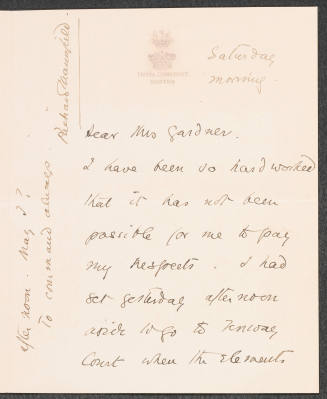

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, Special Collections, Matthew Stewart Prichard MSS · D. Sox, ‘Matt Prichard's story: one bonnet but innumerable bees’, Bachelors of art: Edward Perry Warren and the Lewes House Brotherhood (1991), 165–208 · W. M. Whitehill, ‘Some correspondence of M. S. Prichard and I. Gardner’, Fenway Court (1974), 14–29 [no vol. no.; journal of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum] · M. Luke, David Tennant and the Gargoyle years (1991) · Succession Henri Matisse, Paris, Archives Matisse · Collège de France, Paris, Bibliothèque Byzantine, Fonds Thomas Whittemore · J. D. Ketchum, Ruhleben: a prison camp society (1965) · G. Duthuit, Écrits sur Matisse (1992) · R. Labrusse, ‘La pensée de M. S. Prichard et son influence sur Matisse’, Matisse, Byzance et la notion d'orient, PhD diss., University of Paris I—Sorbonne, 1996, 145–250 · K. E. Haas, ‘Henri Matisse: “a magnificent draughtsman”’, Fenway Court (1985), 36–49 [journal of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum; no vol. no.] · J. W. Pope-Hennessy, Learning to look (1991) · W. M. Whitehill, ‘The battle of the casts’, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: a centennial history, 1 (1970), 172–217 · The letters of T. S. Eliot (1988) · The letters of Bernard Berenson and Isabella Stewart Gardner, 1887–1924, ed. R. van N. Hadley (1987) · Letters of Roger Fry, ed. D. Sutton, 2 vols. (1972) · b. cert. · d. cert. · R. Labrusse, ‘Byzance, un paradigme (Matisse, Prichard)’, Matisse: la condition de l'image (1999), 94–115

Archives

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, Massachusetts, MSS :: Archives Georges Duthuit, Paris · Collège de France, Paris, Bibliothèque Byzantine, Fonds Thomas Whittemore · Succession Henri Matisse, Paris, Archives Matisse

Likenesses

photographs, 1892–1936, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston · photographs, 1892–1936, Succession Henri Matisse, Paris, Archives Matisse · J. B. Potter, drawing, 1905, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston · H. Matisse, engravings, 1914, repro. in M. Duthuit-Matisse and C. Duthuit, Henri Matisse: catalogue raisonné de l'œuvre gravé, 2 vols. (Paris, 1983), nos. 43–4

Wealth at death

£3901 6s. 9d.: administration, 20 Nov 1936, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Rémi Labrusse, ‘Prichard, Matthew Stewart (1865–1936)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/66937, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Matthew Stewart Prichard (1865–1936): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/66937

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1871 - 1950, Washington, DC

Florence, 1856 - 1925, London

Paris, 1879 - 1947, Neuilly-sur-Seine

Garden City, New York, 1861 - 1890, Boston

Berlin, 1861 - 1935, Medfield, Massachusetts

Troy, New York, 1861 - 1933, Boston