Image Not Available

for James Ballantyne and Co.

James Ballantyne and Co.

active Edinburgh and London,

LC Heading: James Ballantyne and Co.

Biography:

Ballantyne, James (1772–1833), printer and newspaper editor, was born at Kelso, Roxburghshire, Scotland, on 15 January 1772, the eldest child of John Ballantyne (1743–1817), general merchant, and Jean (1745?–1818), daughter of James Barclay, rector of Dalkeith high school, and his wife, Elizabeth. His early education was at Kelso grammar school, where in 1783 he first met Walter Scott, who briefly attended the school while staying at Kelso. From 1785 to 1786 Ballantyne attended Edinburgh University, and subsequently was apprenticed to a Kelso solicitor. He returned to Edinburgh University to complete his legal training, and renewed his acquaintance with Scott (both were members of the Teviotdale Club).

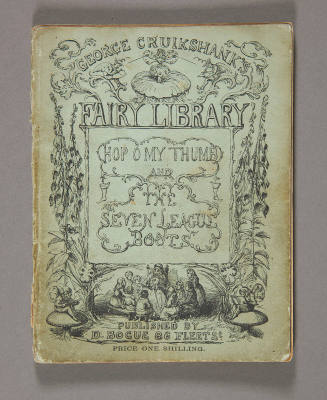

Ballantyne returned to Kelso in 1795 to practise as a lawyer. His first involvement with editing and printing came as a result of being asked in 1796 to be editor of a proposed anti-radical weekly newspaper, the Kelso Mail. The first number of the Mail appeared on 13 April 1797. Ballantyne embraced his new role, travelling to London to make literary and business contacts and to Glasgow to purchase new type. In 1799 Scott proposed that Ballantyne should undertake to print some of his ballads, and twelve copies of a small volume entitled Apology for Tales of Terror were prepared. Scott's recognition of Ballantyne's potential led him to recommend a move to Edinburgh, and to entrust him with the first two volumes of The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, published in 1802 under the Kelso imprint. These books demanded a complex layout and typography, which even at that early stage Ballantyne was able to provide.

In November 1802 Ballantyne moved to Edinburgh, and at Abbey Hill opened a shop with the designation ‘The Border Press’ and equipped with ‘two presses and a proof one’ (Lockhart, Memoirs, 1.378). In 1805 he moved to larger premises, at Paul's Work, and lived nearby, at 10 St John Street. When Scott's The Lay of the Last Minstrel was published to acclaim in January 1805 the quality of the printing was widely acknowledged. A consequent increase in orders meant a need for more capital, and Scott entered into a formal partnership with Ballantyne. The deed of co-partnery of 14 March 1805 noted the mutual advantages to be derived from the agreement and formalized the existing financial arrangement. For the move to Edinburgh Scott had advanced a loan of £500; in order to become an equal but secret partner this became a portion of his investment, with the addition of £1508. Ballantyne's contribution consisted of his property in the printing house, estimated at £2090. For managing the business he was to receive a third of the profits, with the remainder to be divided equally between the partners. Ballantyne became ‘celebrated for his improvements in the art of printing’ (GM, 94). In his negotiations with publishers Scott stipulated that his works were to be printed by James Ballantyne & Co. and that he depended on the printer's attentive eye for detail and careful corrections of his manuscripts and proofs. The connection with Ballantyne became even more important when in 1814 Scott began writing the Waverley novels and strove to keep secret his identity as their author.

The success of the printing company did not mean that it was always conducted in a financially prudent manner, and much of the continued expansion was based on borrowings against Scott's future publications. In 1809 another partnership was formed, to establish a bookseller's business under the care of Ballantyne's younger brother John Ballantyne (1774–1821). James Ballantyne was to receive one fourth of the profits, and works issued by the company were to be printed by his firm. When the resulting dilution of capital funds put the printing business at risk the publishing concern was gradually wound up. In October 1815 Ballantyne's negotiations to marry Christian (d. 1829), daughter of the prosperous Carfrae farmer Robert Hogarth, required his release from partnership in the printing company and any responsibility for its liabilities. Scott became sole owner early in 1816 and Ballantyne was manager at a salary of £400. He married Christian on 1 February 1816. Their son, John Alexander, was born on 29 November 1816, followed by four daughters, one of whom, Mary Scott, died in infancy.

In April 1817, in partnership with Scott and with his brother-in-law George Hogarth, writer to the signet, Ballantyne acquired the Edinburgh Weekly Journal, for which he was to serve as editor and drama critic. His editorials were written in an engaging but prolix style. Their content became the subject of dispute between Scott and Ballantyne during the political unrest of 1819 and 1820. Scott particularly objected to the editorial position criticizing the magistrates' actions in the Peterloo affair. However, when Scott hinted at withdrawing from the journal Ballantyne modified his position. The disagreement did not have a lasting effect on their relationship, and in May 1822 Ballantyne was readmitted as a partner in the printing business; he remained a part-owner with Scott until 1826. When a financial crisis affecting the entire publishing industry resulted in the bankruptcy of Scott's publishers, Archibald Constable & Co., publisher and printer were entangled in a web of mutual obligations and bills. The resulting failure of James Ballantyne & Co. meant that Scott's affairs and those of the printing house were placed in the trust whose debts were eventually paid by Scott's heroic productivity over the final years of his life. Ballantyne reverted to his role as salaried manager of the company. Lockhart attributed the failure to Ballantyne's lack of expertise in financial management and to his excessive personal drawings from the company. This was not, however, Scott's opinion, and his high regard for Ballantyne and for his considerable abilities as a first-rate printer never diminished.

After the financial disaster of 1826 Ballantyne suffered a further blow: the death of his wife, on 17 February 1829. He experienced a severe and prolonged depression. Subsequently he and Scott again quarrelled about politics, this time over Ballantyne's support for the Reform Bill, and although the two continued to communicate about business matters they never resumed their former friendship. Both men were in declining health. Ballantyne, who had always been short and stout, became increasingly corpulent and pompous in later life; in recognition of this Scott called him Aldiborontiphoscophornio. After Scott died, in September 1832, a meeting of his creditors provided Ballantyne with a discharge from his obligation for the printing company's debts. On his sickbed Ballantyne wrote the poignant memorandum of his association with Scott that was later employed by Lockhart in his unfairly critical portrayal. Ballantyne died at his home, in Hill Street, Edinburgh, on 17 January 1833.

Sharon Anne Ragaz, ‘Ballantyne, James (1772–1833)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/1228, accessed 19 Oct 2015]

Person TypeInstitution

Last Updated8/7/24

founded Edinburgh, 1795

Preston, England, 1868 - 1936, London

Black Bourton, England, 1768 - 1849, Edgeworthstown, Ireland

Edinburgh, 1811 - 1890, Aryshire, Scotland

Bishopbriggs, 1818 - 1878, Venice