Ralph Adams Cram

Hampton Falls, New Hampshire, 1863 - 1942, Boston

Cram was first of all an architect, forming his first partnership with Charles Francis Wentworth in 1890. This firm was transformed in 1895 into Cram, Wentworth & Goodhue in 1895 with the addition of the gifted young draftsman Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue. Although the two parted company in 1913, much of Cram's finest work was enhanced through Goodhue's talent for ornamental detail as well as the contributions of the gifted craftsmen the two recruited, including the sculptor Lee Lawrie and the stained-glass artist Charles Connick. The firm's name was changed to Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson in 1899 when Frank Ferguson succeeded the deceased Wentworth; at the time of Goodhue's departure, it became Cram and Ferguson. In 1900 Cram married Elizabeth Carrington Read; they had three children.

Although Cram designed several houses in the Boston area during his early career, it soon became clear that ecclesiastical architecture was his true vocation, and that the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Episcopal church, to which he had been converted in 1888 while attending a Midnight Mass in Rome, was to be his primary object of professional and artistic interest. One of his earliest churches, All Saints', Ashmont, in the Boston suburb of Dorchester (1892), demonstrated his penchant for adapting the Medieval English parish church into a contemporary idiom. Later, more ambitious works, such as St. Thomas Episcopal Church on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan (1914) and the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, taken over by Cram in 1911 and never completed, illustrate his appropriation of French Gothic elements as well as the fruits of his collaboration with Goodhue and their circle of artists and craftsmen.

Although his commissions generally followed his theological and liturgical bent, Cram occasionally undertook projects for other denominations such as East Liberty Presbyterian (1931-1935) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the Polish Catholic St. Florian's in Hamtramck (Detroit), Michigan (1925-1928). He also ventured into collegiate architecture on various occasions, most notably in his collaboration with Goodhue on the fortresslike campus of West Point (1903), an eclectic foray at Rice (1909), and a long-term appointment by Woodrow Wilson as supervising architect of Princeton's Gothic revival campus beginning in 1907. All of those buildings are extant.

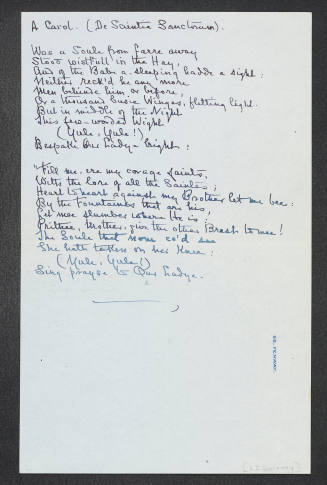

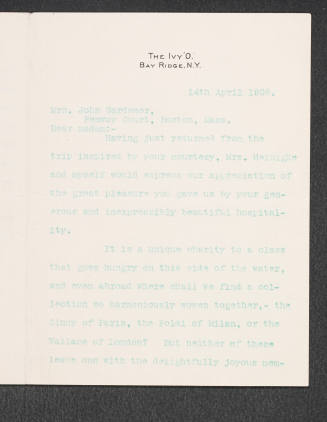

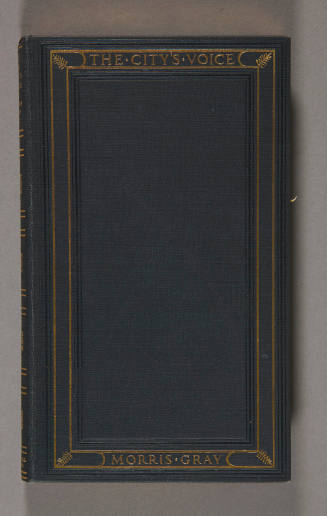

In both thought and action, Cram worked to correlate his architectural practice with a broader scheme of social and cultural transformation based on an ideology of medieval restorationism he developed in nearly countless books and articles. His early writing was more literary than architectural and emerged from the bohemian subculture of fin de siècle Boston. During these years he collaborated with other young and "decadent" literati such as Goodhue, Fred Day, and Louise Imogen Guiney in the production of The Knight Errant (1892), a short-lived periodical.

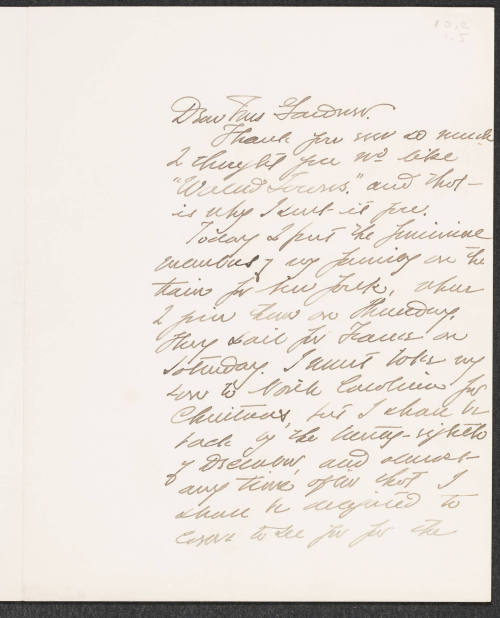

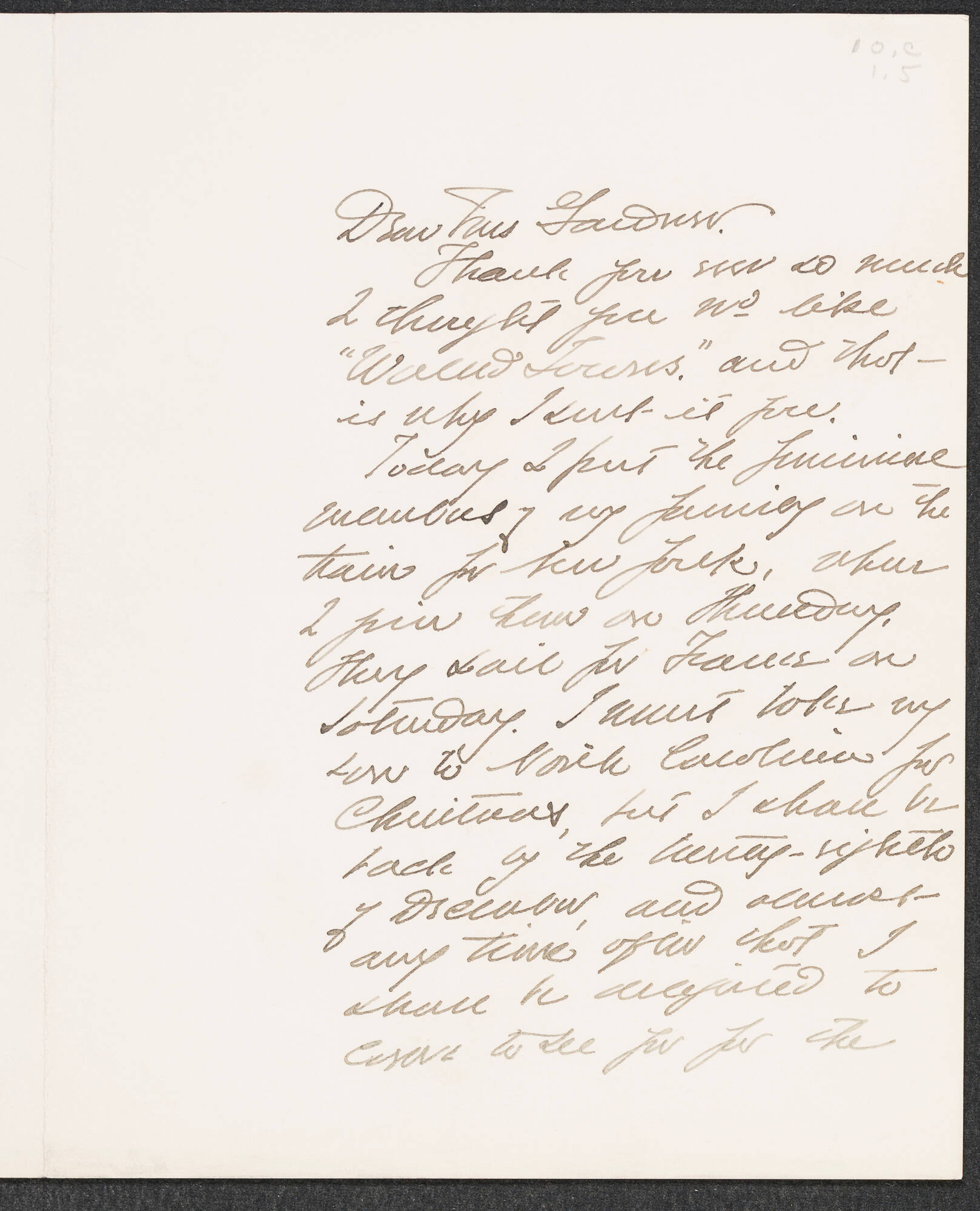

Cram wrote in a variety of genres, including the ghost story Spirits Black and White (1895). In later years he turned to historical and cultural criticism, relentlessly castigating the wrong turnings of Western civilization wrought by the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the French and Industrial Revolutions. In The Gothic Quest (1907), The Substance of Gothic (1917), Walled Towns (1919), and other works, he criticized the linked decline of aesthetics and spirituality in the modern West. He called for a restoration of medievally inspired architecture, such as his own churches, and social institutions based on the principles of hierarchy and interdependence, which he saw in the craft guild and the (Anglo-) Catholic church.

Cram served as chairman of the City Planning Board of Boston from 1914 to 1922, and as head of the Department of Architecture at MIT from 1914 to 1921 despite his lack of the usual academic credentials. He received considerable recognition from contemporaries, appearing on the cover of Time (13 Dec. 1926). In addition he was one of the founders of the influential lay Roman Catholic journal Commonweal (1924) and the Mediaeval Academy of America (1925). He died in Boston and is buried next to his self-designed chapel on the grounds of his estate, "Whitehall," in Sudbury, Massachusetts.

Cram's legacy is problematic. His churches have often been acclaimed as masterpieces of the latter phase of the Gothic revival in the United States, which influenced other religious architects in their concentration on design essentials. Cram himself saw his work as progressive, in the tradition of Henry Hobson Richardson in reaction to the fussiness of Victorian excess. Revivalism of any sort, though, was even during his career overshadowed in both popular taste and elite practice by the forces of modernism represented by native practitioners such as Frank Lloyd Wright and his Prairie School and emigrés such as Walter Gropius of the Bauhaus. The Anglo-Catholic wing of the Episcopal church with which he was affiliated never managed to do more than survive as an option within that tradition, and the costs of building following World War II, together with changes in taste, demographics, and liturgical theology converged against Cram's Gothicism. Elements of his critique of modern civilization were more memorably expressed by Henry Adams, T. S. Eliot, and others, so that little of his published work remains in print or of interest to other than intellectual historians. Almost all of his architectural work has endured, however, and still plays a major role in the cityscape of Manhattan and many other, primarily northeastern, locales. Although hardly triumphant on his own terms, Cram nevertheless left an enduring legacy in the built environment of American religion.

Bibliography

Cram's personal and professional papers, including the records of the firm of Cram and Ferguson, are in the Cram and Goodhue papers at the Boston Public Library. The papers of Cram's long-time partner, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, are in the care of the Avery Library at Columbia University. For a bibliography, see Lamia Doumato, Ralph Adams Cram (1981). Two major studies of Cram are Robert Muccigrosso, American Gothic: The Mind and Art of Ralph Adams Cram (1980), and Douglass Shand-Tucci, Boston Bohemia, 1881-1900 (1995). An extensive study of Cram's architectural work is Ann Miner Daniel, "The Early Architecture of Ralph Adams Cram, 1889-1902" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1978). Illustrations of Cram's architectural work are in Contemporary American Architects: Ralph Adams Cram, Cram and Ferguson (1931) and The Work of Cram and Ferguson Architects (1929). Discussions of Cram include Albert Bush-Brown, "Cram and Gropius: Traditionalism and Progressivism," New England Quarterly 35, no. 1 (1952): 3-22; James F. White, "Theology and Architecture in America: A Study of Three Leaders," in A Miscellany of American Christianity, ed. Stuart C. Henry (1963); Peter W. Williams, "A Mirror for Unitarians: Catholicism and Culture in Nineteenth Century New England Literature" (Ph.D. diss., Yale Univ., 1970); T. J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace (1981); and Richard Guy Wilson, "Ralph Adams Cram: Dreamer of the Medieval," in Medievalism in American Culture, ed. Bernard Rosenthal and Paul E. Szarmach (1989). Also relevant is Richard Oliver, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1983), a biography of Cram's principal collaborator.

Peter W. Williams

Citation:

Peter W. Williams. "Cram, Ralph Adams";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00185.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:10:34 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Pomfret, Connecticut, 1869 - 1924, New York

Neenah, Wisconsin, 1894 - 1984, Bedford, Massachusetts

Boston, 1861 - 1920, Chipping Campden, England

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1871 - 1950, Washington, DC

Boston, 1878 - 1934, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Providence, Rhode Island, 1860 - 1941, Boston