Herbert Allen Giles

Oxford, 1845 - 1935, Cambridge

LC Heading: Giles, Herbert Allen, 1845-1935

Biography:

Giles, Herbert Allen (1845–1935), Sinologist, was born at Oxford on 8 December 1845, the fourth son of the editor and translator John Allen Giles (1808–1884), and his wife, Anna Sarah Dickinson (d. 1896). He was educated at Charterhouse, and in 1867 joined the China consular service as a student interpreter. He made steady progress through the service, reaching the level of vice-consul at Pagoda island in 1880 and at Shanghai in 1883. He was appointed consul at Tamsui (Danshui) in 1886 and at Ningpo (Ningbo) in 1891. He left China late in 1892, formally resigning from the consular service in October 1893.

Giles was twice married: first, in 1870, to Catherine Maria (d. 1882), daughter of Thomas Harold Fenn, of Nayland, Suffolk; second, in 1883, to Elise Williamina (d. 1921), daughter of the biblical scholar Alfred Edersheim. With his first wife he had six sons and three daughters, and with his second wife one daughter. One son, Lionel, also became a distinguished Sinologist and was keeper of the department of oriental printed books and manuscripts at the British Museum.

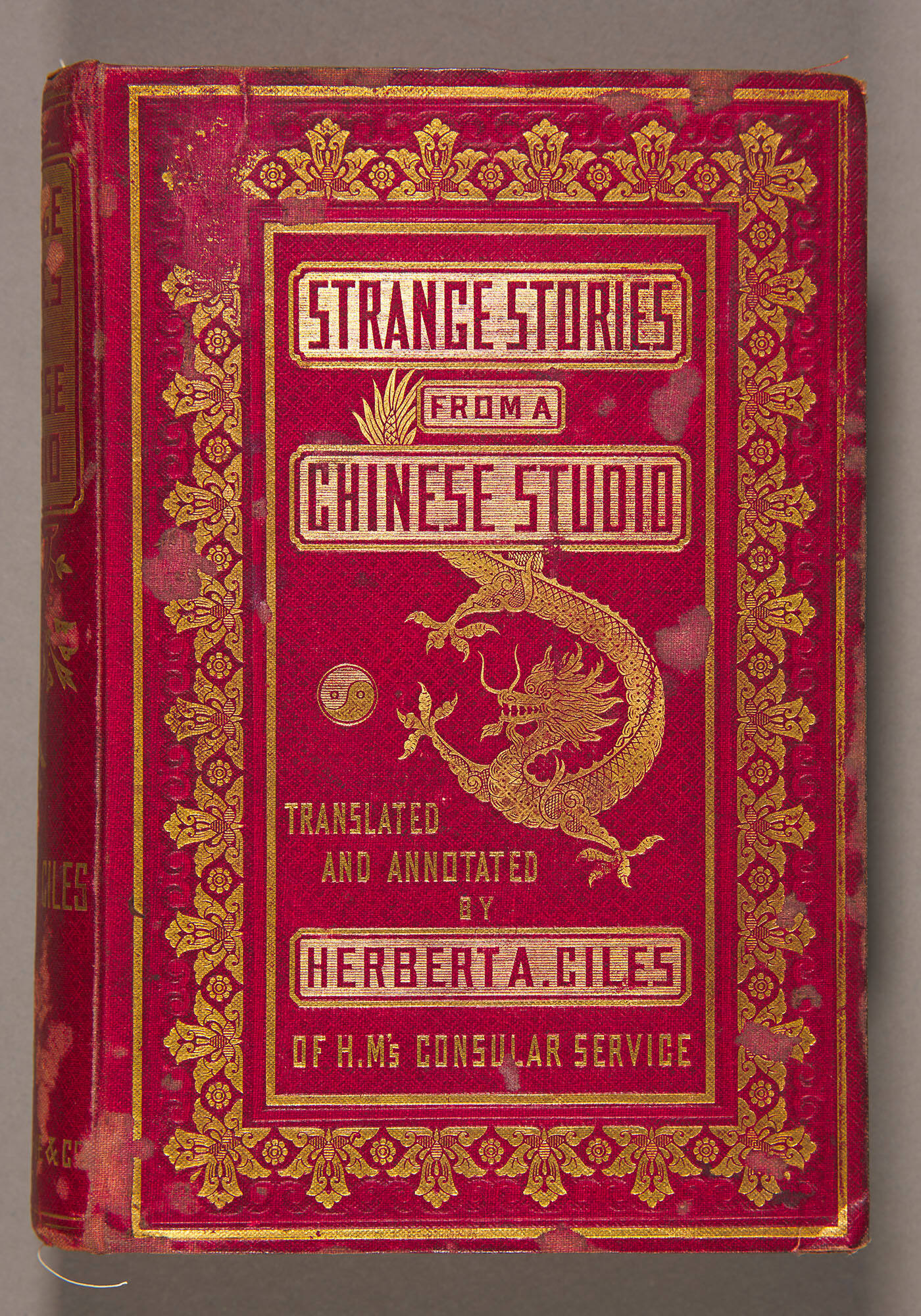

Giles began to write on Chinese history, language, and literature in the early 1870s, and within a few years had completed a Mandarin phrase book, a language guide in the Swatow dialect, further guides to Mandarin, and a large number of translations and historical and descriptive works on China. By the end of the 1870s he had published more than a dozen works on Chinese subjects. In 1874 he began work on a Chinese–English dictionary, which was finally published in 1892, and on which rested most of his subsequent reputation. Building on the work of Sir Thomas Wade, the transliteration system Giles set out in his dictionary became accepted as standard. The ‘Wade–Giles’ system was abolished for external use by China only in 1979 and until the early 1990s was still used by many Western institutions.

Following his return from China, Giles lived in Aberdeen until 1897 when he replaced Wade as professor of Chinese at Cambridge. Contemporaries differed in their views of Giles's success as a professor. There was little student interest in Chinese studies at Cambridge, and it has been suggested that Giles's personality—‘naturally combative’—alienated many, and limited the support he received from colleagues or the university (Marshall, 524–5).

Giles's clearest contribution to Chinese studies was his ability through his writings to ‘humanize’ China for a Western audience. His clear and flowing style and his understanding of China meant, said one contemporary, that he was ‘able to breathe life’ into his subjects (Shang-Ling Fu, 85), and his translations were praised for capturing the spirit of the original works. Yet he was also criticized for what even his supporters admitted was his lack of attention to small details. This remained a major criticism of Giles, perhaps put most harshly by E. G. Pulleybank, who said that Giles's work ‘suffers very much from the disease of amateurism, a fundamental lack of serious scholarly discipline’ (Pulleybank, 3). Despite this, Giles was a highly significant Sinologist, both for the long-lasting impact of his transliteration work and for the fundamental part he played in kindling interest in Chinese studies in the West. In an eightieth birthday tribute, a colleague said that Giles's ‘most notable work has been that of making the study of Chinese language and literature easier for students ... We are all his debtors’ (Ferguson, 2).

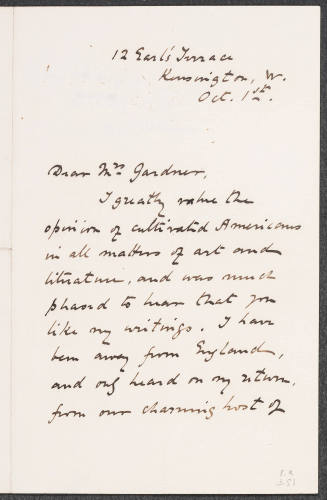

Giles was punctual and methodical, and regarded as an excellent conversationalist, yet his most remembered characteristic was always his readiness to enter into an argument, leading one writer to call him a ‘fanatical type ... always furiously taking sides no matter right or wrong’ (Moule, 577). Between the 1870s and the 1920s Giles published nearly sixty works on China. He received honorary degrees from the universities of Aberdeen (1897) and Oxford (1924), was awarded the order of Jiahe by the Chinese government and the gold medal of the Royal Asiatic Society, and twice awarded the prix St Julien by the French Academy. He resigned from his professorship in 1932 and died at his home, 10 Selwyn Gardens, Cambridge, on 13 February 1935.

Janette Ryan

Sources A. C. Moule, ‘Herbert Allen Giles’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1935), 577–9 · The Times (14 Feb 1935), 7 · WWW · Shang-Ling Fu, ‘One generation of Chinese studies at Cambridge’, The Chinese Social and Political Science Review, 15 (1931–2), 78–91 · P. R. Marshall, ‘H. A. Giles and E. H. Parker: Clio's English servants in late nineteenth-century China’, The Historian, 46 (1983–4), 520–38 · E. G. Pulleybank, Chinese history and world history (1955) · D. E. Pollard, ‘H. A. Giles and his translations’, Renditions: a Chinese-English Translation Magazine, 40 (autumn 1993) · Cambridge Review (22 Feb 1935) · J. C. Ferguson, ‘Dr Giles at 80’, China Journal of Science and Arts, 4/1 (1926) · FO List (1903), 123 · A. J. Arberry, British orientalists (1943), 46 · B. Hook, ed., The Cambridge encyclopedia of China, 2nd edn (1991), 337 · I. L. Legeza, Guide to transliterated Chinese in the modern Peking dialect, 1, 2 (1968), 17

Archives CUL, unpublished typescript and MSS

Likenesses photograph, repro. in Ferguson, ‘Dr Giles at 80’

Wealth at death £23,614 12s. 8d.: probate, 1 April 1935, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

Janette Ryan, ‘Giles, Herbert Allen (1845–1935)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/33401, accessed 2 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Fockbury, England, 1859 - 1936, Cambridge, England

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1870 - 1927

Crowthorne, 1862 - 1925, Cambridge, England