Image Not Available

for T.J. Cobden-Sanderson

T.J. Cobden-Sanderson

Alnwick, Northumberland, 1840 - 1922, London

LC Heading: Cobden-Sanderson, T. J. (Thomas James), 1840-1922

found: Wikipedia, Sept. 17, 2013 (T.J. Cobden-Sanderson; Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson; b. 2 December 1840, Alnwick, Northumberland, as Thomas James Sanderson, d. 7 September 1922; English artist and bookbinder associated with the Arts and Crafts movement; cofounder of the Doves Press) {http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T._J._Cobden-Sanderson}

Biography:

Sanderson, Thomas James Cobden- (1840–1922), bookbinder and printer, was born Thomas James Sanderson on 2 December 1840 at Alnwick, Northumberland, the only son of James Sanderson (c.1813–1895), a district surveyor of taxes, and his wife, Mary Ann Rutherford How (1800–1891). James Sanderson's career took his family from place to place, and his son was educated in Worcester, Hull, Pocklington, and Rochdale. From 1857 to 1859 he studied at Owens College in Manchester, and in 1860 he went to Trinity College, Cambridge. He lost his Christian belief at Cambridge, and left in 1863 without taking a degree.

To describe Cobden-Sanderson as a bookbinder and printer is to identify him with the things for which he is known, but it gives a false impression of the man. It would be truer to describe him as ‘thinker, bookbinder, and printer’, not because his thoughts were original or profound, but because he lived on such a high intellectual plane. As a young man he read Carlyle, Goethe, Spinoza, Wordsworth, and the pioneering geographer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt; these were lifelong intellectual companions. But he was also anguished and lonely, thinking high thoughts to turn away the pain. He limped through the 1860s, not knowing what to do with his life, suffering long periods of depression, sometimes talking of suicide. German idealism and romantic poetry simply magnified his unhappiness, giving it a heroic dimension.

Towards the end of the decade Sanderson felt stronger and took up the law, practising as a barrister in London from 1871 to 1883. He was involved in making ‘a kind of Code of all the powers, rights, and obligations of the London & North-Western Railway Company’ (Cobden-Sanderson, Cosmic Vision, 114). Shifting this mass of legal details was like mining, he recalled, but at the end there was no gold and his health was broken. He went to Italy to recuperate.

In the 1860s Sanderson had got to know Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, perhaps through his Cambridge friend George Howard, later ninth earl of Carlisle. In April 1881, outside the duomo in Siena, he met Morris's wife, Janey, with Annie and Janie Cobden, daughters of the radical MP Richard Cobden. In the following year, on 5 August, he married Julia Sarah Anne (Annie) Cobden (1853–1926), changing his name to Cobden-Sanderson out of respect for her father. He was forty-one and she was twenty-nine. He wrote later that ‘her active and practical mind gave to my own that feeling for reality which it had long been in want of’ (Cobden-Sanderson, Cosmic Vision, 115). This was a turning point. Nearly a year later he was again with Janey Morris. He was eager to do work with his hands, in the spirit of the arts and crafts movement, and she suggested bookbinding. Two days later he went to the bookbinding workshop of Roger de Coverley, and asked to be taught. This was another turning point.

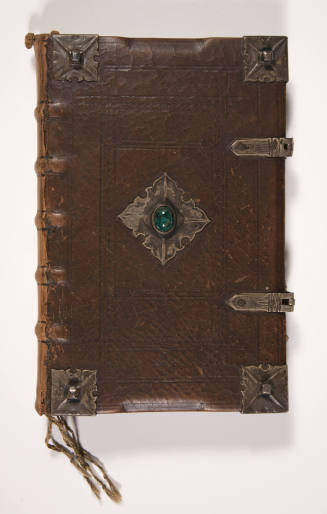

De Coverley's was one of a number of firms in the London bookbinding trade which bound individual books for customers using traditional methods. Cobden-Sanderson spent about six months there and then set up on his own in 1884, working first in Covent Garden and then from home in Hendon and Hampstead. He also bound individual books, but he chose what he bound, which was not the usual practice in the trade. From 1886 onwards he bought books, rebound them, and took them to the bookseller James Bain in Haymarket, where they sold enough to earn him a modest living. (Annie had brought a small inheritance to the marriage.) From the late 1880s many of his bindings were sold to American customers, and the two principal modern collections of bindings designed by Cobden-Sanderson are American: the Strouse Collection at the University of California at Berkeley and that of J. Paul Getty junior.

Cobden-Sanderson thought of bookbinding as the clothing of fine literature, and Shakespeare, the English romantic poets, Tennyson, and Morris were the writers whose works he bound most. The more he admired a work the more sumptuously he bound it. He worked in gold on leather, using simple, mainly floral tools of his own design, and his rich effects brought a kind of springtime to the French and English binding traditions on which he drew. He seemed to have found his métier. He worked as a binder for only about ten years, but he started a tradition of fine binding in Britain which continues to the present day.

Cobden-Sanderson had found his métier late in life, and he had never been strong. By the early 1890s he no longer had the strength for heavy work. In 1893 he took a lease on 15 Upper Mall, Hammersmith, a small house with a garden running down to the Thames, near William Morris's own Kelmscott House. Here he started the Doves Bindery, employing three professional binders and naming it after a nearby pub. At first the bindery worked as he had, binding individual books to his designs, and selling them through Bain. But when he started printing books at the Doves Press in 1900, it began to do more repetitive work, binding whole editions of Doves Press books in plain vellum.

Four years after starting the Doves Bindery, the Cobden-Sandersons moved with their two children, Richard and Stella, from Hampstead to 7 Hammersmith Terrace, a short walk from Upper Mall, and from this date Cobden-Sanderson lived and worked among the houses, wharves, and workshops that lined the river's edge at this point. Other luminaries of the book arts—Morris himself, the process engraver Emery Walker, the calligrapher Edward Johnston—lived near by.

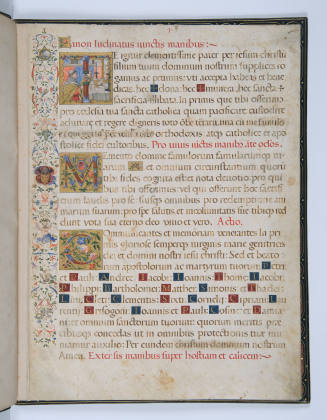

In 1900 Cobden-Sanderson set up the Doves Press at 1 Hammersmith Terrace, in partnership with Emery Walker. This was as distinct from trade printing as his bookbinding had been, a private press on the lines of Morris's Kelmscott Press. He and Walker wanted to print great literature in monumental form, and to see if they could make a book beautiful with type alone. Goethe, Wordsworth, Milton, and Shakespeare were among the chosen authors and, as their masterpiece, the Bible. Some fifty titles were printed between 1900 and 1917. They are similar in layout and they all employ the Doves type, which Walker derived from a fifteenth-century Venetian model. There are no illustrations and no ornaments, apart from some initials drawn by Edward Johnston and Graily Hewitt; just the words printed with care on handmade paper. As with his sumptuous bindings, this austerity expressed Cobden-Sanderson's reverence for the canon of western literature. In the early twentieth century it was a visual model for the reform of typography in Britain, Europe, and America.

In photographs of the 1880s Cobden-Sanderson looks much younger than he was, shrimp-like, unformed, clean-shaven. In those of c.1900, on the other hand, he has a fine beard and moustache and looks his sixty years. He sits the very image of the artist-craftsman in an embroidered sky-blue smock, his normal dress at this time. He had come into his own. It was partly that he had married, but perhaps more that he had picked up his binder's tools. After all the Weltschmerz of his early years, it was little humble things, leather and type, that had shown him what to do. He was now a leader of the arts and crafts movement in England. The course of his life ran more smoothly. And his speculative mind came happily into play around the practical world of printing and binding. He saw the history of the world as a God-filled process of physical and spiritual evolution, and the history of man as its dialectical complement. He felt as though the work of his hands kept time with the movement of the universe. Unfortunately this ‘cosmic vision’, as he called it, was not easy to convey. In lectures he talked persuasively about bookbinding or typography, but as he moved towards his larger theme he became childlike and rhetorical; the words came too easily. When he told his audience that the ideal book was ‘a symbol of the infinitely beautiful in which all things of beauty rest and into which all things of beauty do ultimately merge’, they were not always sure what he meant (Cobden-Sanderson, The Ideal Book, 9). Arts and crafts colleagues admired his work, but did not always understand him.

Towards the end of his life Cobden-Sanderson did one mean-spirited thing in the name of his cosmic vision. He was restless in partnership with Walker at the Doves Press, because he put more into the work of the press than Walker, who had his own business to run. The partnership was dissolved in 1908, but Walker claimed part-ownership of the Doves type. In 1909 Cobden-Sanderson (the older man) signed an agreement whereby the type would be his for life, and would pass to Walker at his death. But he did not trust Walker to use the type in the spirit of his vision. During the war he brought the printing to an end. On many evenings in the autumn and winter of 1916, under cover of darkness, he took the Doves type and threw it into the Thames off Hammersmith Bridge. It was a dedication (he had been reading the book of Leviticus); a symbolic act (giving his work back to the river of life); an old man's act of folly; and a betrayal. In May 1917 he wrote to Walker's lawyers explaining what he had done, and his letter was published in the Times Literary Supplement.

The Doves Press closed down in 1917. At this point the Cobden-Sandersons went to live at 15 Upper Mall, where two binders continued working in a small way until 1921. Cobden-Sanderson died at home on 7 September 1922, and following his cremation at Golders Green on 11 September the urn containing his ashes was placed in the garden wall of 15 Upper Mall. Annie Cobden-Sanderson died in 1926 and her urn was placed with his. Two years later there was a severe flood and the Thames overflowed its banks. It seems that both urns were washed away.

Alan Crawford

Sources The journals of Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson, 1879–1922, 2 vols. (1926) · M. Tidcombe, The Doves Bindery (1991) · M. Tidcombe, The bookbindings of T. J. Cobden-Sanderson (1984) · T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, The ideal book or book beautiful (1900) · T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, Cosmic vision (1922) · W. Ransom, ed., Kelmscott Doves and Ashendene: the private press credos (1952) · J. H. Nash, ed., Cobden-Sanderson and the Doves Press (1929) · T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, Amantium irae: letters to two friends, 1864–1867 (1914) · B. Middleton, ‘English craft bookbinding, 1880–1980’, Private Library, 4/4 (winter 1981), 139–69 · C. Franklin, Emery Walker: some light on his theories of printing and on his relations with William Morris and Cobden-Sanderson (1973) · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1922)

Archives BL, working diary · BL, binding work book · Hunt. L., pattern books · Ransom HRC, photograph album · Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts, corresp. and MSS · U. Cal., Berkeley, Strouse Collection, binding patterns, corresp. and MSS, photographs :: BL, corresp. with S. Cockerell, 52710 · Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, corresp. with G. Howard · Hammersmith and Fulham Archives and Local History Centre, letters to W. Bull

Likenesses W. Crane, sketch, 1881, repro. in W. Crane, An artist's reminiscences (1907), 221 · P. Lombardi, photograph, 1881, NPG · group portrait, photograph, 1881, NPG · photograph, c.1890, U. Cal., Berkeley, Bancroft Library · A. Legros, etching, 1898, repro. in Catalogue raisonné of books printed & published at the Doves Press, 1900–1916 (1916) · photograph, c.1900 (with Emery Walker), repro. in Philobiblon [Vienna], 9 (1932) · photograph, c.1905, V&A · photograph, c.1910, Hammersmith and Fulham Libraries, London · W. Rothenstein, drawing, 1916, repro. in W. Rothenstein, Twenty-four portraits (1920) · W. Rothenstein, engraving, 1916, NPG [see illus.] · group portraits, photographs (with his family), Ransom HRC

Wealth at death £12,988: probate, 30 Oct 1922, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Alan Crawford, ‘Sanderson, Thomas James Cobden- (1840–1922)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/32470, accessed 22 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Blackburn, England, 1838 - 1923, Wimbledon, England

Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1857 - 1924, Bishopsbourne, England

Rochdale, England, 1811 - 1889, Rochdale, England