Image Not Available

for Juliana Horatia Ewing

Juliana Horatia Ewing

Ecclesfield, England, 1841 - 1885, Bath, England

Biography:

Ewing [née Gatty], Juliana Horatia (1841–1885), children's writer, was born in the vicarage at Ecclesfield, near Sheffield, on 3 August 1841, the second of eight children of Alfred Gatty (1813–1903), Church of England clergyman, and his wife, Margaret Gatty, née Scott (1809–1873). Educated primarily by her mother, Juliana (Julie) was the leader in the children's botanical, theatrical, and literary activities, and their chief story-teller. She was known as Aunt Judy not only to her family but to the readers of her mother's works: Aunt Judy's Tales (1859), Aunt Judy's Letters (1862), and Aunt Judy's Magazine (1866–82). In the parish as well as the vicarage, she and her three sisters were as good as curates—better, because unpaid—but she was enthusiastic in this work, and was responsible for establishing the Ecclesfield village library. Her first stories appeared in Charlotte Yonge's Monthly Packet, and in book form in 1862 (Melchior's Dream and other Tales). Apart from one youthful Gothic tale, she concentrated her professionalism and perfectionism on children's stories and verse, eventually making an eighteen-volume SPCK series. Most of her work appeared first in Aunt Judy's Magazine. After their mother's death, she and her sister Horatia assumed the editorship, but after two years her sister continued as sole editor.

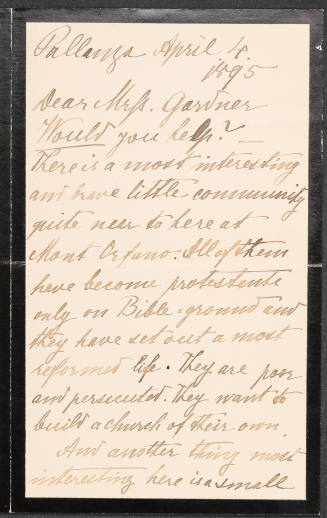

In 1866, Juliana Gatty renewed acquaintance with Major Alexander (Rex) Ewing (1830–1895) of the army pay department. His church connections, talents, and tastes suited a family where books, music, and animals were abundant, but his financial prospects were poor, and she was deemed too delicate for army life. Despite initial discouragement, they married with the Gattys' blessing on 1 June 1867, and embarked within days for Canada. They spent two years in Fredericton, New Brunswick, as the colony adjusted to its new status as part of the Canadian confederation. Juliana Ewing's reassuring letters home are full of lively details and sketches; she and her husband were a happy couple, sharing many interests. They studied with John Medley, the bishop, and were stalwarts of the cathedral, where her husband played the organ and composed hymns. Juliana Ewing continued to contribute to Aunt Judy's Magazine, concluding Mrs. Overtheway's Remembrances (1866–8; 1869) from Canada, and sending the first of a series of Old-Fashioned Fairy-Tales (1869–76; 1882), in emulation of the oral folk-tale. Only when they were ordered home did her homesickness become evident, and their return to Ecclesfield, accompanied by a rescued dog and innumerable botanical specimens, was a triumphal occasion.

Alexander Ewing was posted next to Aldershot, where they lived very happily until 1877, although Ethel Smyth's impressions of Juliana at this time are not entirely sympathetic. Her admiration for military life grew, although it was never wholly uncritical; ‘Jackanapes’ (1869; 1883) celebrated military honour in the face of a civilian standard of judgement she thought increasingly material and commercial. ‘The Story of a Short Life’ (1882; 1885) similarly presented a military ethos as a source of great strength and goodness. In addition to short stories, the Aldershot years saw three longer works: A Flat-Iron for a Farthing (1870–71; 1872), Six to Sixteen (1872; 1875), and Jan of the Windmill (1872–3; 1876). The second of these, a novel about an orphan girl growing up, Rudyard Kipling claimed to have known almost by heart. It drew upon her husband's knowledge of India, and her own early memories of her Ecclesfield home.

Juliana Ewing's Anglican faith and practice were a source of great strength to her; unlike her mother, she felt no need to preach it explicitly, though the values of service, self-denial, and generosity are frequent themes in such stories as ‘The Brownies’ (1865), ‘Lob-Lie-by-the-Fire’ (1874), and ‘Madam Liberality’ (1873). The Baden-Powells borrowed the idea of the brownies for the younger branch of the Girl Guides; in the person of Madam Liberality her family recognized Julie herself.

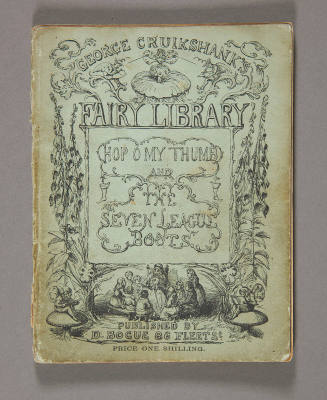

After Aldershot, the Ewings entered an unsettled period, living briefly near Manchester and York, before Alexander Ewing was posted to Malta in 1879. Despite ill health, Juliana planned to follow in the autumn, but got no further than Paris before breaking down. She returned to England, where she stayed with relatives and friends, hoping for better health. William Jenner diagnosed neuralgia of the spine; she continued to be unable to travel, and frequently exhausted herself with work. Her husband was posted to Ceylon in 1881, and his remittances to his wife were often insufficient. Disappointed that she made so little from her books, she almost took Ruskin's advice to declare herself independent of a commercial publisher, but she gave Daddy Darwin's Dovecote (1881; 1884) to Bell as usual. In an attempt to reach a broader audience, she republished poems in illustrated shilling books. Herself a talented visual artist, she habitually took great pains in discussions with her illustrators, among them George Cruikshank and Randolph Caldecott.

Alexander Ewing returned in 1883, and they settled outside Taunton in Somerset, where Juliana Ewing established a garden and wrote Mary's Meadow (1883–4; 1886) and letters on gardening for Aunt Judy. Her ‘neuralgia’ (probably cancer) grew worse; she went to Bath, underwent two operations, and died there on 13 May 1885. Her grave in the Trull churchyard, near Taunton, where she was buried on 16 May, was so heaped with flowers from admirers that no soil was visible. Realistic and rarely over-sentimental, her books were greatly admired by E. Nesbit, and they retain their attraction for the reader who appreciates humour, country life, happy but interesting families, and a sensibility distinctly but not dismally Victorian.

Susan Drain

Sources H. K. F. Eden, Juliana Horatia Ewing and her books (1885) · C. Maxwell, Mrs Gatty and Mrs Ewing (1949) · Canada home: Juliana Horatia Ewing's Fredericton letters, 1867–1869, ed. M. H. Blom and T. E. Blom (1983) · G. Avery, Mrs Ewing (1961) · M. Laski, Mrs Ewing, Mrs Molesworth, and Mrs Hodgson Burnett (1950) · C. Mills, ‘Choosing a way of life: Eight cousins and Six to sixteen’, Children's Literature Association Quarterly, 14/2 (1989), 71–5 · D. E. Hall, ‘We and the world: Juliana Horatia Ewing and Victorian colonialism for children’, Children's Literature Association Quarterly, 16/2 (1991), 51–5 · J. Plotz, ‘A Victorian comfort book: Juliana Ewing's The story of a short life’, ed. J. H. McGarran, Romanticism and children's literature in nineteenth-century England (1991), 168–89 · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1885)

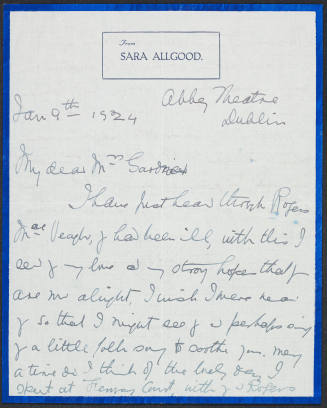

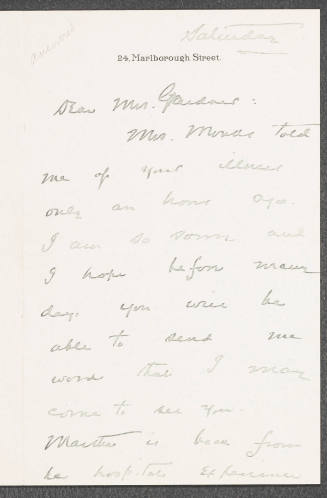

Archives Sheff. Arch., corresp., diaries, commonplace book, and MSS :: U. Reading L., letters to George Bell & Sons Ltd, publishers

Likenesses F. Hollyer, photograph, National Museum of Photograph, Film and Television, Bradford, Royal Photographic Society collection [see illus.] · F. Largs, photograph, repro. in Eden, Juliana Horatia Ewing · photograph, repro. in Maxwell, Mrs Gatty and Mrs Ewing

Wealth at death £3015 0s. 10d.: probate, 21 Sept 1885, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Susan Drain, ‘Ewing , Juliana Horatia (1841–1885)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/9019, accessed 27 Oct 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Chester, England, 1846 - 1886, Saint Augustine, Florida

Weimar, 1849 - 1922, Trebschen

Northamptonshire, 1851 - 1924, Oxford

Lancaster, Ohio, 1852 - 1925, Boston