George Copeland

Boston, 1882 - 1971, Princeton

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Copeland accessed 6/20/2019

George Copeland (April 3, 1882 – June 16, 1971)[1] was an American classical pianist known primarily for his relationship with the French composer Claude Debussy in the early 20th century and his interpretations of modern Spanish piano works.

Career

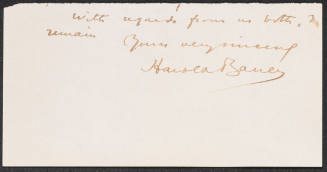

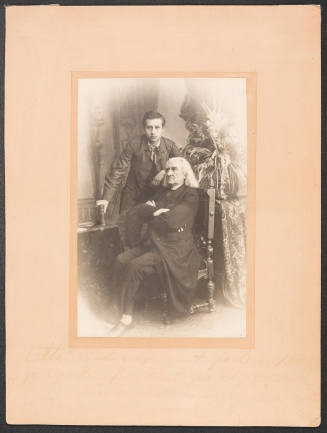

A native of Massachusetts, George A. Copeland Jr. began piano studies as a child with Calixa Lavallée, the composer of "O Canada" and an important early member of the Music Teachers National Association (MTNA).[2] Copeland later worked at the New England Conservatory with Liszt pupil Carl Baermann, then traveled to Europe for studies with Giuseppe Buonamici in Florence and Teresa Carreño in Berlin.[3] Copeland was also coached in Paris by the British pianist Harold Bauer, concentrating on works of Schumann.[4] Early in the 20th century, Copeland fell in love with the works of then-unfamiliar French composer Claude Debussy. On January 15, 1904, Copeland gave one of the earliest-known performance of Debussy's piano works in the United States, playing the Deux Arabesques at Steinert Hall in Boston.[5] Copeland was not the first to perform Debussy in the United States; that honor went to Helen Hopekirk, a Scottish pianist who programmed the Deux Arabesques in Boston in 1902.[6] From 1904 until his final recital in 1964, Copeland played at least one work of Debussy on each of his recitals.

In the early 1900s, John Singer Sargent, a fellow Bostonian, introduced Copeland to Spanish music.[7] Copeland became an Iberian specialist, performing works of Isaac Albéniz, Enrique Granados, Manuel de Falla and others throughout the United States and Europe. In 1909, he introduced three of Albéniz's Iberia suite to the United States, playing "Triana," "Malaga" and "El Albaicin" in Boston.[8]

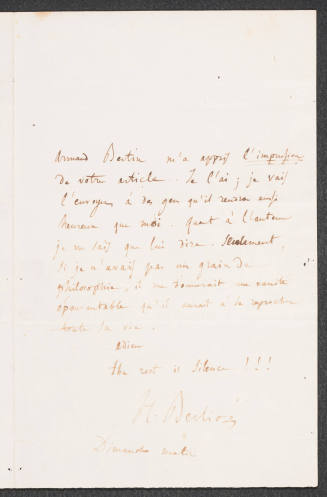

In 1911, he met Debussy in Paris and spent four months studying with the composer, discussing and playing all of Debussy's piano works. This was a turning point in Copeland's life; until his death 60 years later, Copeland would recall his time with Debussy with the greatest affection and reverence, both in print and in conversation with friends. In 1913, Copeland gave the following account of their discussions:[9]

"I have never heard anyone play the piano in my life who understood the tone of every note as you do," remarked Debussy. "Come again tomorrow." This seemed praise indeed and I did go tomorrow. I found him much more genial than on my first visit, and then I went time after time, until finally I was with him about twice a week for three months. I bought new copies of his works, which he marked for me; I played his works and he criticised my work and showed me what to do and how to do it. In the end, he admitted that I played him just as he wanted to be played and represented to the people.

By 1955, Copeland had modified his account to have Debussy say: "I never dreamed that I would hear my music played like that in my lifetime.[10] In this later version, Copeland claimed that their meetings were daily, for four months, including periods of playing as well as long walks in the countryside.

Copeland gave many U.S. premieres of Debussy's works, as well as several world premieres. The most important was the world premiere of numbers X and XI of the Etudes on November 21, 1916, at Aeolian Hall in New York City.[11] The anonymous critic for Musical Courier was not particularly impressed with the Études, writing "These [études], in themselves, are not so absorbing as some of the composer's more familiar pieces, but as played by Mr. Copeland they acquired a delicate tone and glowing imagery that were surpassingly beautiful."[12] Other U.S. premieres of Debussy included the Berceuse héroïque and La Boîte à joujoux. The latter, played on March 24, 1914 at the Copley-Plaza Hotel in Boston, may have been the world premiere of the work.[13]

From 1918 through 1920, Copeland toured the United States with the Isadora Duncan Dancers, the "Isadorables"), a sextet of dancers who were the students and adopted children of dancer Isadora Duncan.[14] Sponsored by the Chickering Piano Company and managed by Loudon Charlton, Copeland and the dancers performed a shared program of dance and piano solos including works of Schubert, Chopin, MacDowell, Debussy, Grovlez, Albeniz, and others.[15] The reviews of Copeland were overwhelmingly positive, though many reviewers were less enthusiastic about the dancers[16] Annoyed at Copeland's success, the girls ordered Loudon Charlton to put Copeland in his place. The program covers were accordingly changed to read in large font "THE ISADORA DUNCAN DANCERS," with Copeland's name appearing in a smaller font beneath. Copeland saw this and refused to go onstage until all of the offending program covers in the audience had been removed.[17] In the spring of 1920, Copeland abruptly broke his contract for unknown reasons and went to Europe. Years later, Copeland told his student Ramon Sender that breaking his contract had fatal consequences for his career and that when he returned to the United States in the 1930s, no reputable manager would touch him.[18]

Living first in Italy, then on the island of Mallorca,where he lived in the village of Genova and had a good relationship with the neighbours becoming the godfather of Juana Maria Navarro, the daughter of one of his better friends. Copeland returned to the United States only periodically, giving Carnegie Hall recitals in 1925, 1928–1931 and 1933.[19] In 1930, he performed in Philadelphia and New York City with the Philadelphia Orchestra led by Leopold Stokowski, offering works of Debussy and De Falla. While living in Europe, he played at the Chopin Festival of Majorca, in Vienna with the Wiener Philharmoniker, at the Salzburg Festival, and in London. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Copeland returned to the United States.

Settling in New York City, he performed there annually at venues including Carnegie Hall, Town Hall and Hunter College, and made regular trips to Washington D.C. and Boston. In 1945, he toured with the soprano Maggie Teyte in an all-Debussy duo recital that included his arrangement of Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune.[20] Copeland played a Golden Jubilee Recital at Carnegie Hall on October 27, 1957, celebrating the 50th anniversary of his New York recital debut. The New York Times reviewer described his performance as "magical," calling Copeland's work "playing that stays in the memory."[21] In the spring of 1958, he suffered a fall at his vacation home in Stonington, Connecticut and broke his shoulder. He was unable to play for several years and believed his career to be over.[22] In 1963, he made a comeback, recording with famed engineer Peter Bartok and concertizing at schools and smaller halls on the East Coast. On May 11, 1964, Copeland performed his final recital at Sprague Memorial Hall, Yale University. Although he spoke in 1966 of a return to the concert stage, he never again performed in public.[23]

Copeland died of bone cancer in the Merwick Unit of Princeton Hospital in Princeton, New Jersey, on June 16, 1971. His cremated remains are held at the Ewing Cemetery in Ewing, New Jersey.[24]

Personal life

Copeland was open about being gay throughout his life. In 1913, he gave an interview to the Cleveland Leader in which he stated "I don’t care what people think of my morals. I never think anything about other people’s morals. Morals have nothing to do with me."[25] He indicated that Oscar Wilde was a favorite author.[26]

Throughout his life, the pianist delighted in exotic jewelry and scents, both considered effeminate in the early 20th century. He wrote in his unpublished memoirs:[27]

I have always had a passion for wearing jewelry, and whilst I know it is considered bad form, forbidding men to wear anything but a tiresome signet ring, I have taken the liberty of defying that convention all my life. Probably it grew out of my father's attitude. He was going to give me a watch on my birthday, and he asked me what kind I wanted. I wanted a wristwatch – they were still a rare novelty in those days. He said I could certainly have the wristwatch if I wanted it, but that I need never darken his door again. Men who wore jewels or wristwatches, or who used perfume, or anything that smelt agreeable, were considered effeminate. I felt if my masculinity or effeminacy were to be judged and decided by the bottle of scent, or the kind of jewel I wore, I had best give up! Jewels are another manifestation of beauty, and certainly perfume smells better than perspiration! I wear jewels because I love to look at them myself, and because I hope they give pleasure to others. They are not unrelated to music, for all music has color – the deep greens of forests, the limpidness of water, the passionate flash of rubies and diamonds.

Copeland's openness about his sexuality allegedly led to problems for composer Aaron Copland. In the 1930s, the pianist preceded the composer on a concert tour in South America. In one country George Copeland was apprehended on a "morals charge" and told never to return. When Aaron Copland arrived for his concerts, the authorities treated him frostily before he explained that he was Copland the composer, not Copeland the pianist.[28]

Around 1936, Copeland met a young German, Horst Frolich, at a restaurant in Barcelona, and they began a relationship that lasted for over thirty years. Frolich returned to the United States with Copeland that year, listing his occupation on the ship manifest as "secretary."[29] According to friends of the pianist, Copeland was adamant about Frolich's position as his partner; if you wanted the socially-desirable pianist to attend your party, Frolich had to be invited.[30] A December, 1942 New York Times social item reporting the guest list of a high-society gathering at the St. Regis in New York included Copeland, the violinist Fritz Kreisler and Frolich. Frolich committed suicide in 1972 after a dispute involving a property he was to inherit from a different lover.[31]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Calais, Maine, 1860 - 1952, Waverly, Masachusetts

Newport, Rhode Island, 1842 - 1901, Phoenix, Arizona

New Malden, Kingston-upon-Thames, England, 1873 - 1951, Miami, Florida

Kharkov, Ukraine, 1863 - 1945, New York

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris