Jacob Tonson

English, 1656 - 1736

Biography:

Tonson, Jacob, the elder (1655/6–1736), bookseller, was born in London, the second son of Jacob Tonson (1620–1668), a barber surgeon, and his wife, Elizabeth Walbancke (b. 1631), whose brother was the bookseller Matthew Walbancke; Kathleen Lynch claims that he was baptized at St Andrew's, Holborn, on 12 November 1655. Little is known about Jacob's youth, but his later ease with Latin suggests he was given a good classical education. In 1668 his elder brother Richard (1653–c.1700) was apprenticed to the Walbancke firm, and on 6 June 1670 Jacob was apprenticed to the stationer Thomas Basset. Richard Tonson set up his own publishing firm in 1676, and Jacob did the same when he completed his apprenticeship on 7 January 1678. For some time, the brothers published books jointly, and in partnerships with other publishers. Jacob's first publication on his own was an undistinguished, anonymous fictional piece, God's Revenge Against the Abominable Sin of Adultery (1678).

Early publishing success

Tonson, however, quickly moved to more important books when in 1679 he began publishing the works of John Dryden, soon becoming his exclusive publisher; Absalom and Achitophel (1681) was Tonson's first widely celebrated publication. He began to buy up the rights to Dryden's earlier works during the 1680s, and he also began publishing a wide range of the most important writers of the age, including Aphra Behn and the earl of Rochester. During these years Tonson also learned the power of publicity, and he was one of the first booksellers to advertise in the newspapers. This combination of shrewd business practices and first-rate literature soon made Tonsons the most prestigious place for authors to be published. By collecting and reprinting the works of authors like Dryden, he helped turn them into accepted modern classics.

Dryden and Tonson collaborated on a highly significant series of anthologies and compilations of translations. The first was Ovid's Epistles (1680), with translations by seventeen different hands; owing to Dryden's literary intelligence and Tonson's business sense, the book had far greater success than translations usually did, going through numerous editions. Between 1683 and 1686 (the year in which he became a liveryman of the Stationers' Company) Tonson and Dryden produced a five-volume set of Plutarch's Lives, which employed forty-two translators; it too sold very well, and went into later editions. In the mid-1680s about half Tonson's list consisted of translations; he and Dryden were creating a public taste for such work. Even more important, however, were the anthologies or miscellanies that the two devised. The first, Miscellany Poems, included Dryden's ‘MacFlecknoe’ as well as work by many other contemporary poets. The book's success led to sequels, and it is no exaggeration to say that Tonson created the modern anthology as a genre, one which also whetted the public's appetite for other works by the poets included. One such poet was Alexander Pope, whose first publication came in Tonson's sixth miscellany (1709); Tonson's anthologies guaranteed the poet, especially the young poet, a much wider audience than he might otherwise have been able to find.

Milton

Another major author associated with Tonson was John Milton. Tonson read Milton's Paradise Lost when it was originally published in 1667. When Milton died in 1674, Tonson was still apprenticed to Basset, and he once spent his weekly free day—Sunday—going to the recently deceased poet's house in the hope of buying some books from his library. In 1683 Tonson purchased half the rights to the poem, and acquired the other half in 1690. Paradise Lost had had moderate success before Tonson, some 3000 copies having been printed, but it by no means occupied the place it does today in the canon of English literature. Tonson was highly instrumental in creating and nurturing an audience and an appreciation for the poem and for Milton, keeping the poet's reputation alive in a period dominated by a very different literary taste.

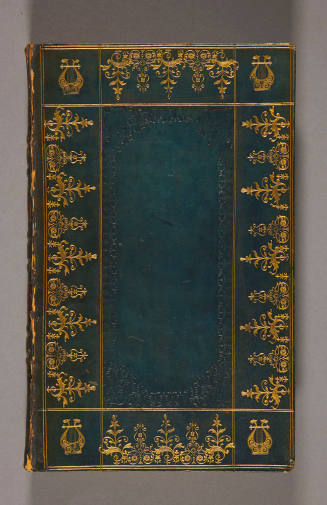

Tonson bought not only the rights to the poem but the first edition's corrected manuscript as well, indicating that he saw Paradise Lost as having serious, lasting literary value. He did not print the poem, however, until 1688—perhaps because the political atmosphere before that date would not have favoured the work of a puritan revolutionary poet. Tonson approached the 1688 edition with great care: he was careful about the text itself, consulting the three previous printings as well as Milton's manuscript, and making some important emendations. The book was printed, by subscription, in a large folio, with careful and attractive typography. Tonson also paid for illustrations by John Baptist Medina, which, together with the sumptuous look of the book, made a possibly daunting poem more immediately interesting and approachable. As a frontispiece, Tonson printed an engraving of Milton, with six lines by Dryden below it, designed to claim Milton as the great English poet, transcending his puritan times and deserving celebration by the new aesthetic and political regime. Tonson remained closely involved with Milton's works for the rest of his life, and in the famous Kneller portrait he is depicted holding the folio edition of Paradise Lost. He was protective not only of his copyright but of the quality of Milton's text, and he bitterly criticized an edition put out in the 1730s for its mangling of the poem. Much later in life, when he was asked what poet had made the most money for him, he replied, ‘Milton’. There is no doubt that Tonson valued Milton for the money he could make, but it is also clear that he was committed to Milton's literary excellence, which he had perceived early on. Tonson's enthusiasm led him to continue to promote Milton, whom he printed in a variety of editions over the years. His edition of 1695 included scholarly annotations by Patrick Hume, effectively declaring Milton a permanent classic. It is not too much to say that Milton's literary reputation was in large part nurtured and ensured by Tonson's efforts.

Translating the classics

After the revolution of 1688 Tonson's political sympathies turned increasingly whiggish, while his most famous living author, the Catholic and pro-Stuart Dryden, fell out of political favour. None the less, their relationship remained strong in the 1690s, though Dryden at least once complained of Tonson's stinginess. He sent Tonson a triplet that served as a threat of the sort of satire he could write if Tonson did not agree to his demands; the lines provide an interesting caricature portrait:

With leering look, bull faced and freckled fair

With frowsy pores poisoning the ambient air,

With two left leggs, and Judas coloured hair.

(Poems of John Dryden, 1766)

‘Two left leggs’ refers to Tonson's odd manner of walking; he had experienced trouble with his feet since his childhood. Later satirists used the image as well, referring to Tonson's shop as under the sign of two left feet. None the less, for all their occasional quarrelling, Dryden and Tonson remained on good terms.

Dryden continued to do translation work for Tonson. The translation of Juvenal and Persius (1693) ushered in the notion of translation as a kind of modernization, of making the translated author, as Dryden put it, ‘speak that kind of English, which he wou'd have spoken had he liv'd in England, and Written to this Age’ (The Satires of Decimus Junius Juvenalis, lii). Translation as imitation came to dominate English verse for the next couple of generations; the Persius and Juvenal volume again sold very well, with several succeeding editions. But the most important project Tonson and Dryden undertook was a translation of all of Virgil, first mentioned in 1694. Tonson paid Dryden £200 in advance, a very significant sum, and set about publicizing the work in advance. Using the experience of the Milton volume of 1688, Tonson found over 500 subscribers for the book, which appeared in June 1697 as one of the most eagerly awaited books of the season. The book is one of Tonson's finest achievements in terms of typography, layout, and illustrations (over 100 of them); Dryden added an essay on Virgil, and Joseph Addison contributed a brief introduction to each section. King William was one of the many looking forward to the book, and hinted that he would look favourably on its being dedicated to him, a suggestion that Dryden, naturally, found intolerable. But Tonson cleverly worked around the issue: he had some of his workmen alter the illustrations slightly so that Virgil's Aeneas resembled William. Tonson's main profits from the book came with later, cheaper reprints, but his gain in prestige as the country's finest publisher of literary works was beyond valuation.

The Kit-Cat Club

After Dryden's death in 1700 Tonson printed many editions and collections of his works; as with Milton, Dryden's work was a matter of financial profit as well as something to be guarded and promoted for its high literary value. Tonson never abandoned Dryden, despite the political gulf that widened between them. Having become closely involved with the leading whigs during the 1680s, Tonson was a founding member of the Kit-Cat Club, which included virtually all the most powerful whig politicians from 1688 to 1710. An anonymous satire from 1704 calls Tonson the founder of the club, and it quickly became the best-known of the exclusive men's clubs, with much gossip circulating about its members and their doings. Tonson was evidently an enthusiastic and well-liked host, and was nicknamed Bocaj (Jacob backwards) in poems about the club. By 1703 the group had grown too large for Christopher Cat's tavern, and soon thereafter Tonson used the members' dues to build a special clubroom at his residence in Barn Elms, Surrey. Tonson commissioned Sir Godfrey Kneller to paint portraits of forty-eight of the Kit-Cats—including the dukes of Newcastle and Somerset, the earls of Dorset and Essex, and others including Cornwallis and Godolphin—as well as Tonson himself. The club included writers as well, such as Congreve, Addison, and Steele.

Robert Walpole once referred to the Kit-Cats as the men who had saved the kingdom, meaning that they had played a central role in establishing the Hanoverian succession. Tonson himself was never directly involved in politics, but he seems to have been respected by the other members, and it is possible that he at least gathered some intelligence for the group when he went to the continent to purchase paper and other printing necessities. Vanbrugh believed that Tonson secretly went to Hanover in 1703 to carry some messages, and he may have spied on Matthew Prior in France in 1714 when Prior was negotiating between the tory administration and the exiled Stuarts. If the latter is true, there was evidently no ill will between the two men, as Tonson went on to publish a luxurious edition of Prior's poems in 1718. But the exact extent of Tonson's involvement in any espionage remains, not surprisingly, uncertain. In any case, whatever political activity he involved himself in never got in the way of his continuing dedication to his publishing.

Tonson continued to publish plays including the most popular play of the period, Addison's Cato (1713), for whose copyright he paid Addison the then astronomical sum of £107. Tonson spearheaded the Kit-Cats' efforts to fund the building of the new Queen's Theatre in Haymarket, London, as well as other projects, including one to encourage the production of better-quality plays. But the Kit-Cats, despite their cultural endeavours, became increasingly a group dedicated to party politics, and there were purges of anyone in any way connected with the tories. Their strong solidarity, with Tonson as host and organizer, produced some of the whigs' greatest triumphs, such as the Act of Settlement with the Regency (1701), which established the legal basis for the Hanoverian succession, and the Act of Union with Scotland (1707). When George I took the throne in 1714, he rewarded the club members generously; but without the binding pressure of being in opposition the group began to weaken, meeting less and less regularly. When Tonson made an extended trip to France in 1718–20, the club evaporated altogether.

Later publications

Among Tonson's major publications during the Kit-Cat years is his great folio edition, in Latin, of the works of Julius Caesar; some nine years in the making, it finally appeared in 1712. No English publisher had ever produced so lavish a book before, with its careful scholarship (the texts were edited by Samuel Clarke), its numerous maps, and its eighty-seven engravings done in superb detail by Dutch artists. The book was dedicated to the duke of Marlborough, and had as its frontispiece Kneller's portrait of Marlborough. Again, this was published by subscription, and in this case Tonson arranged to have each subscriber's coat of arms printed on each double-plate page. He employed John Watts as printer for this edition, and the two worked together on several classical texts over the succeeding decade. In 1713, for instance, Tonson published editions of Lucretius, Terence, Justin, Salust, Pompey, and Aesop, and in 1714 an edition of the Greek New Testament. In the following years he put out editions of Ovid, Catullus, Horace, and Lucan, among many others. His greatest achievement in these years was a sumptuous English edition of Ovid's Metamorphoses which, as in the early years of the Dryden partnership, employed a set of different translators. Tonson reprinted many of his existing Ovid translations (including some by Dryden), but he also employed Samuel Garth to find new translators and to oversee the project. Alexander Pope satirized the project in his ‘Sandys' Ghost’ (1717), referring to George Sandys, the Elizabethan translator of Ovid. Pope finds comedy in the idea of Tonson and Garth beating a drum for volunteer translators:

I hear the beat of Jacob's Drums,

Poor Ovid finds no Quarter!

(Minor Poems, 172)

When the troops of volunteers are finally lined up, Tonson goes out to review them:

Now, Tonson, list thy Forces all,

Review them, and tell Noses;

For to poor Ovid shall befal

A strange Metamorphosis.

A Metamorphosis more strange

Than all his Books can vapour;

‘To what, (quoth 'Squire) shall Ovid change?’

Quoth Sandys: To Waste-Paper.

(Minor Poems, 174)

The edition appeared in 1717, dedicated to Princess Caroline, with a Kneller portrait of her as frontispiece, in quarto format with numerous illustrations; a nice marketing touch was having each of the fifteen books of the Metamorphoses dedicated to a different noblewoman. The edition proved highly successful despite Pope's sneers (Pope himself being engaged in the translation of Homer that was to make his own fortune); indeed, Tonson's Ovid was reprinted as late as the nineteenth century.

Establishing the Tonson dynasty

About 1700 Tonson's nephew Jacob Tonson the younger (1682–1735) began working for him. The younger Jacob was born in London, the son of Tonson's brother Richard, and over the ensuing fifteen years the younger Jacob increasingly came to run the daily affairs of the Tonson business, until the elder Jacob retired about 1718, with his trip to France in 1718–20 effectively easing him out of it. The younger Jacob had demonstrated energy and ability almost the equal of his uncle's: one of his most important achievements was the purchase of over 100 titles owned by Henry Herringman in 1707, a lot that included three plays by Shakespeare. The elder Jacob had also been actively trying to purchase Shakespeare copyrights, though the details of the sales—and indeed whether some vendors actually owned the copyrights at all—remain unclear.

The elder Jacob Tonson looked on Shakespeare's works as he had Milton's and Dryden's, both as being works of great literary and national value, and as being generators of profit for his firm. He hired Nicholas Rowe, the dramatist, to edit an edition of Shakespeare, which appeared in 1709. Rowe was a responsible editor, if not the most scholarly one, and many of his textual emendations and stage directions remain accepted today. Moreover, his biographical essay was designed to interest the general reader in Shakespeare, and both it and the edition were highly successful in popularizing the plays. The edition was reprinted many times in the coming years.

The younger Jacob Tonson, however, thought the market for Shakespeare insufficiently tapped, and in 1721 he approached Alexander Pope to put together a new edition. The elder Tonson was also enthusiastic about the idea, and he acquired a copy of the First Folio (1623) to help Pope deliver an edition with greater textual integrity than ever before. The Pope edition came out in 1723 (volumes 1–5) and 1725 (volume 6). But Pope, brilliant poet though he was, proved disastrous as an editor: he frequently made ‘improvements’ in Shakespeare's verse, going as far as dropping entire scenes and soliloquies that he felt violated the plays' unity. Lewis Theobald, an inferior poet but a superior scholar, published an attack on the Pope edition in 1726, entitled ‘Shakespeare restored’; Pope was enraged by Theobald's presumption, and set about making him the central figure in his dark satire The Dunciad. This left the Tonsons to choose which side they ought to be backing, and to their credit they joined several other publishers in producing Theobald's new edition (1733). In this, however, they were merely facing up to reality, for the Copyright Act of 1709 dictated that their own rights to Shakespeare expired in 1731.

Jacob Tonson the elder, before leaving for his trip to France, signed over all his copyrights—a list that included some twenty-three authors—to his nephew, for £2597 16s. 8d. The younger Tonson hoped he would be heir to his uncle's fortune, even conferring with his uncle's long-time servant about how best to stay on the old man's good side (the servant recommended gifts of food). When the uncle returned in 1720 he gave his Barn Elms estate to his nephew, moving to a new estate, The Hazels, in Ledbury in 1722, where he entertained many of his old Kit-Cat associates. Pope visited him at The Hazels, once inviting his friend the earl of Oxford along, promising him that he would find old Tonson fascinating, ‘the perfect Image & Likeness of Bayle's Dictionary [that is, a virtual encyclopedia]; so full of Matter, Secret History, & Wit & Spirit’ (Correspondence, 176). During these years Tonson the elder also speculated in the stock market, his canny business sense helping him again: he sold out his shares in the doomed South Sea project before the crash, making a profit on a scheme that ruined many others. The younger Jacob Tonson's hopes for his inheritance came to nothing, for he predeceased his uncle, at Barn Elms on 25 November 1735, leaving a fortune of £100,000. His uncle died soon after, on 18 March 1736, at The Vineyard, an estate between Gloucester and Ledbury; his fortune was reported as much less, £40,000, though it certainly was much greater than that. Tonson the elder was buried at St Mary-le-Strand, London, on 1 April 1736.

With his wife, Mary Hoole, the younger Jacob had two sons, Jacob Tonson (1714–1767) and Richard Tonson (1717–1772), and they inherited the business. Of the two, Jacob was by far the more engaged in publishing. He carried on his father's and great-uncle's enthusiasm for Shakespeare, hiring William Warburton for his important edition of 1747, and publishing Samuel Johnson's of 1765. Johnson spoke warmly of him, and there are anecdotes of his helping indigent authors such as Henry Fielding with their debts. The firm also produced editions of authors from the old list, such as Milton and Congreve. But the two brothers never had any major impact on publishing, and seemed content to maintain the reputation gained by the preceding generations. Jacob Tonson died on 31 March 1767, in London; he had no children. His brother Richard, who had little to do with the publishing business, was elected MP for Wallingford in 1747, and for New Windsor in 1768. He lived near Windsor, building a special room for the display of Kneller's Kit-Cat portraits. He died on 9 October 1772, also leaving no children. The Tonson copyrights passed on to the Rivington publishing firm. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, letters of administration of the goods of Jacob Tonson were left unadministered by his brother and were granted in 1775 to William Baker, MP for Hertfordshire; he too failed to administer and they were granted to Joseph Rogers in 1823.

The Tonson house made significant contributions both to publishing and to English literature. In particular, the elder Jacob Tonson's concern with textual integrity in authors such as Milton and Shakespeare marked his house as one concerned with high-quality publishing defined in the broadest possible way; the typography and layout in his greatest works—such as the Dryden Virgil or the edition of Julius Caesar—set new and distinguished standards. Combining such values with excellent business sense made the Tonson company highly profitable for the better part of three generations.

Raymond N. MacKenzie

(Raymond N. MacKenzie, ‘Tonson, Jacob, the elder (1655/6–1736)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/27540, accessed 23 Dec 2015])

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Southwater, England, 1675 - 1736, London