Edward Everett Hale

Boston, 1822 - 1909, Roxbury

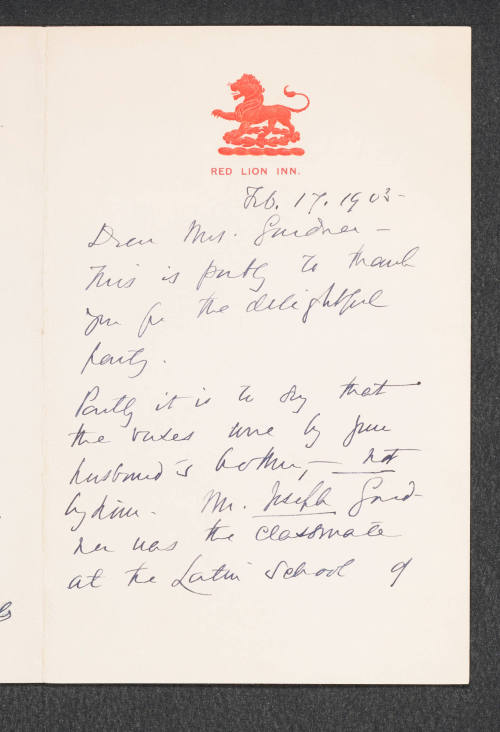

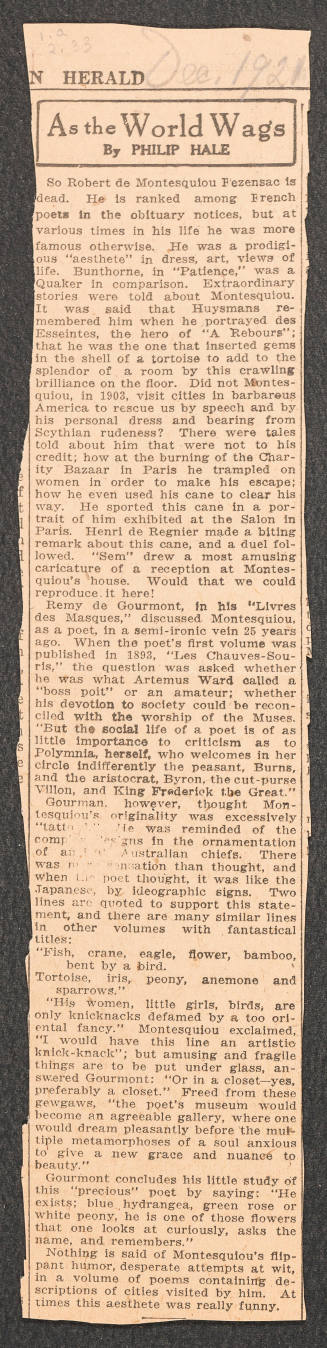

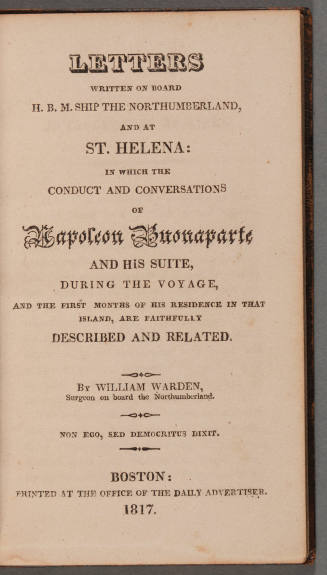

After teaching Latin at the Boston Latin School for two years, Hale gained invaluable journalistic experience working as a legislative reporter on Boston's first daily paper, the Daily Advertiser, which his father owned and edited from 1814 to 1854.

Meanwhile, through private study, Hale also prepared for the ministry and was licensed to preach in 1842. He spent the next four years as a substitute preacher until he felt he was ready to be ordained. In 1846 he became a minister to the Congregationalist Church of the Unity in Worcester, Massachusetts.

During those years as a substitute preacher Hale embarked on a career as a writer of stories and, later, novels and essays, which he pursued throughout his long life, and which brought him to national prominence. Unable to sell his first stories, Hale contributed them to the Boston Miscellany, which his brother Nathan edited. His first printed story, the somewhat allegorical "A Tale of a Salamander," was published in January 1842 and was the first of some 100 stories Hale published during the next fifty-five years.

But Hale's interests extended beyond mere storytelling, for he felt his writings should have some didactic purpose. Further, since he was raised in the privileged Brahmin world of antebellum Boston and was personally acquainted with eminent figures such as Henry Clay and Daniel Webster as well as Ralph Waldo Emerson, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Julia Ward Howe, Hale developed an active social conscience. He thus used his journalistic skills to publicly oppose slavery as early as 1845 in his pamphlet A Tract for the Day: How to Conquer Texas before Texas Conquers Us, in which he advocated Texas's admission to the Union as a free state. He later expanded the theme in 1854 in his book Kanzas [sic] and Nebraska (incidentally, the earliest book written on Kansas), in which he proposed mass emigration from the northern states into Kansas as a means of ensuring its becoming a free state.

In 1852 Hale, the outspoken abolitionist, married Emily Baldwin Perkins of Hartford, Connecticut, the niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Henry Ward Beecher and the granddaughter of Lyman Beecher. They had eight children.

After serving ten years in the ministry in Worcester, in 1856 Hale left to accept the post of pastor of the South Congregational Church in Boston, a position he held until his resignation in 1899. During this long tenure Hale's reputation as a writer grew, and he became what William Dean Howells described as "an artist in his ethics and a moralist in his art."

With the September 1859 Atlantic Monthly publication of his first successful and important story, "My Double and How He Undid Me," Hale received national acclaim. This humorous tale of an overworked clergyman who hires a slow-witted lookalike to fill in for him at tedious meetings was widely anthologized. The minister's plan of having the double make only one of four all-purpose clichéd responses when spoken to, such as "I agree, in general, with my friend on the other side of the room," eventually backfires on the cleric. Among Hale's stories, this work represents one of his dominant types of tales, the humorous anecdote; the other type is the serious fable, although as his biographer John R. Adams pointedly observed, "This distinction is only moderately helpful since most of his humorous tales develop a serious purpose." Straddling this line is a class of his sociological fables that take the form of utopian fantasies, such as his novella Sybaris (1869) and "The Brick Moon" (1869), a proto-science fiction story that presents the earliest fictive account of an artificial earth satellite.

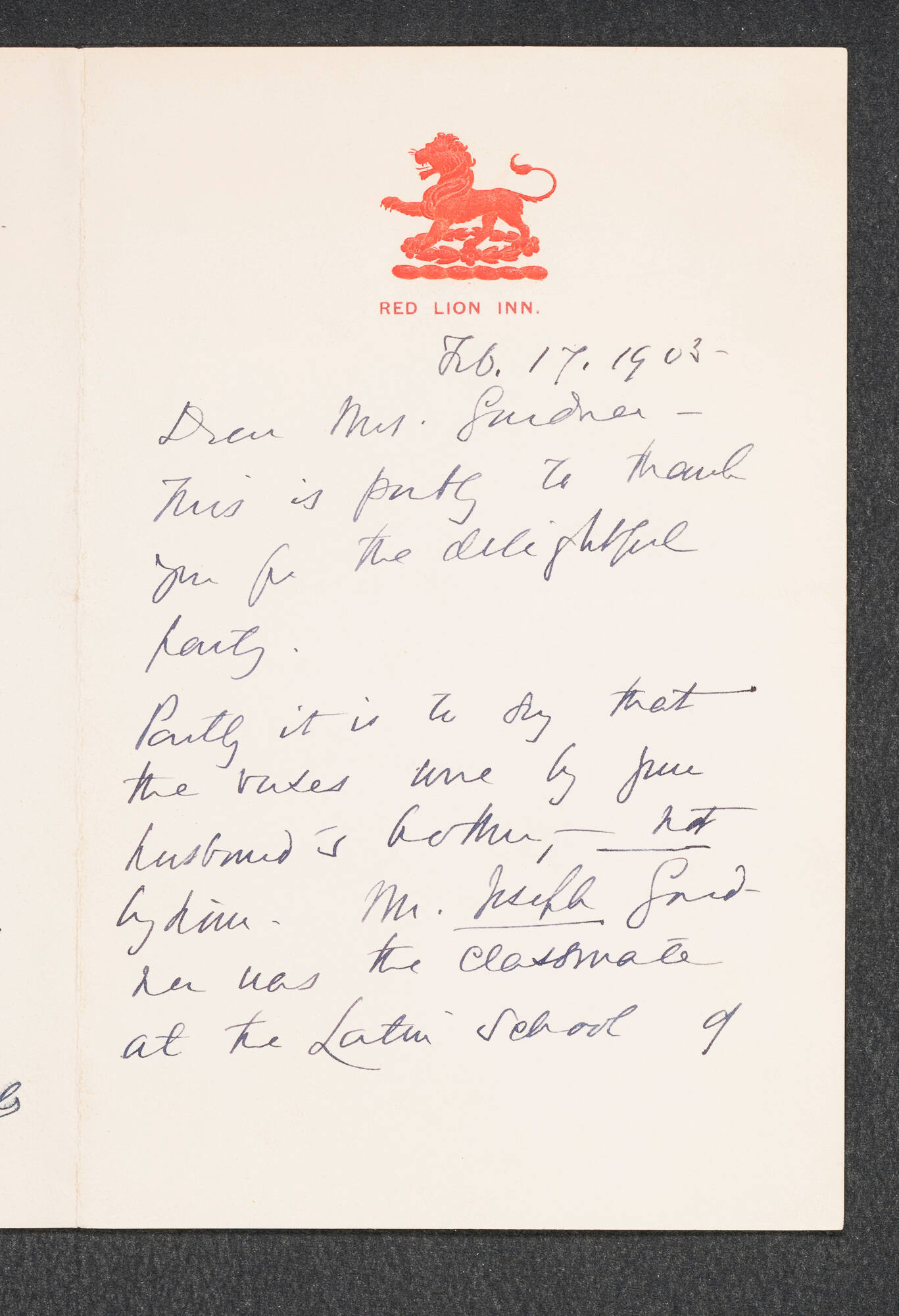

Perhaps the most serious of Hale's purposeful stories is "The Man without a Country" (1863). Although written during the Civil War to rally support for the Union generally, and specifically to influence the Ohio electorate to vote against the Peace Democratic candidate for governor, Clement L. Vallandigham, "The Man without a Country" was not published in the Atlantic Monthly until December 1863, too late to influence the Ohio election (in which Vallandigham was, at any rate, defeated). Yet this story made a far greater impact than its author could have imagined, for it became a minor American classic and is the story for which Hale is best known. "The Man without a Country" is the tale of the traitor Philip Nolan, who upon conviction said in court that he wished, "I may never hear of the United States again!" His punishment was lifelong banishment from the United States in the form of confinement at sea on a series of some twenty naval vessels over the course of fifty-six years.

This work created so strong a sentiment that even twenty-two years later it was hailed in Century magazine as "the best sermon on patriotism ever written" and as having done "much, and will do more, to foster the idea of national unity." Furthermore, at Hale's death the story was described in the Nation as "probably the most popular short story written in America." Still, there was also a minority view by the turn of the century that the story was "the primer of jingoism."

In the years following the Civil War Hale's national prominence and liberal theological views led him to help establish the Unitarian Church of America. An indication of the inclusiveness of Hale's Christian belief and his distance from the more fundamentalist views of the day is evident in an essay Hale wrote in 1886: "For myself, I can attend the service of the Roman Church with pleasure and profit. If I find myself in a Catholic town in Europe, where there is no Protestant Church, I always go to worship with the Catholics."

Another aspect of Hale's increasingly popular public career is best encapsulated in remarks he made in 1871 in his Alpha Delta Phi address: "Noblesse oblige, our privilege compels us; we professional men must serve the world . . . as those who deal with infinite values, and confer benefits as freely and nobly as nature." This theme of promoting good works through social action is embodied in many of his books, especially Ten Times One Is Ten (1871), and several of his eighteen novels, as well as in a number of his stories published in the magazine he founded in 1869, Old and New. The premise of Ten Times One Is Ten is that doing good for others can create a positive chain reaction: if the one helped goes on to help ten others, and then those ten each help yet another ten, the expansion of goodness would be geometrical, resulting in what Hale called a "Happy World!"

Hale's "athletic morality" was not lost on one Harvard junior who first met with Hale in the 1870s. In fact Theodore Roosevelt became one of Hale's enthusiastic supporters and, as president, described Hale as "one of the most revered men in or out of the ministry in all the United States." Hale's association with Roosevelt and his successor, William Howard Taft (whose inauguration Hale attended), spanned a century of the American presidency, for as a young man Hale had been the guest of Dolley Madison and also John Quincy Adams in their homes.

With advanced age many accolades came to Hale. So highly esteemed had he become that for a civic ceremony to welcome the new century, before a crowd gathered on the Boston Common, he was asked to read the Nineteenth Psalm at midnight on 31 December 1900 from the balcony of the Massachusetts State House. After retiring from his chuch post in 1899, Hale was nationally honored in 1903 by being unanimously elected chaplain of the U.S. Senate, a position he held into the last year of his life. In 1904 he was among the first ten writers elected to membership in the newly established Academy of Arts and Letters. At his death in Boston Hale was effusively eulogized. The Review of Reviews, for example, described him as "a more truly national personage, in his knowledge and sympathies, than were any of the other New England thinkers and leaders" (July 1909, p. 79).

Although Hale's popularity as a writer has long faded, his work provides, as John R. Adams observed, "a mirror of his period. . . . He is more significant as an educator and as a journalist than as a creative writer." Indeed, while best remembered as the author of "The Man without a Country," his reform-minded advocacy of a variety of issues, from the abolition of slavery and improved race relations to religious tolerance, public education reform (to include half-year schooling and the abolition of grades and examinations), and even government regulation of monopolies and expanded public ownership, is most notable. Edward Everett Hale may well be viewed, to use Theodore Roosevelt's words, as "an American of whose life all good Americans are proud."

Bibliography

The principal collection of Hale's papers is in the New York State Library in Albany. Other major collections of his papers and letters are at the Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif.; the Massachusetts Historical Society; the Library of Congress; the Houghton Library at Harvard; the American Antiquarian Society; the John Hay Library at Brown University; the Princeton University Library; the University of Rochester; and the Beinecke Library at Yale. In addition to Hale's own autobiography, Memories of a Hundred Years (1902; rev. and enl., 1904), two reliable biographies exist: The Life and Letters of Edward Everett Hale (1917), by his son Edward Everett Hale, Jr., and Jean Holloway, Edward Everett Hale: A Biography (1956). Holloway also compiled the definitive checklist of Hale's writings in three installments in the Bulletin of Bibliography 21 (May-Aug. 1954, Sept.-Dec. 1954, and Jan.-Apr. 1955). John R. Adams's critical assessment of Hale's life and career, Edward Everett Hale (1977), is highly estimable. Other useful accounts include William Sloane Kennedy, "Edward Everett Hale," Century, Jan. 1885, pp. 338-43. Obituaries are in the New York Times, 11 June 1909; Nation, 17 June 1909; and Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings 43 (1910): 4-16.

Francis J. Bosha

Back to the top

Citation:

Francis J. Bosha. "Hale, Edward Everett";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00682.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:13:38 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Edward Everett Hale, (born April 3, 1822, Boston, Mass., U.S.—died June 10, 1909, Roxbury, Mass.), American clergyman and author best remembered for his short story “The Man Without a Country.”

A grandnephew of the Revolutionary hero Nathan Hale and a nephew of Edward Everett, the orator, Hale trained on his father’s newspaper, the Boston Daily Advertiser, and turned early to writing. For 70 years newspaper articles, historical essays, short stories, pamphlets, sermons, and novels poured from his pen in such journals as the North American Review, The Atlantic Monthly, and Christian Examiner. From 1870 to 1875 he published and edited the Unitarian journal Old and New. “My Double and How He Undid Me” (1859) established the vein of realistic fantasy that was Hale’s forte and introduced a group of loosely related characters figuring in If, Yes, and Perhaps (1868), The Ingham Papers (1869), Sybaris and Other Homes (1869), His Level Best (1872), and other collections. “The Man Without a Country,” which appeared first in The Atlantic Monthly in 1863, was written to inspire greater patriotism during the Civil War. East and West (1892) and In His Name (1873) were his most popular novels.

Hale’s ministry, which began in 1846, was characterized by his forceful personality, organizing genius, and liberal theology, which placed him in the vanguard of the Social Gospel movement. Many of his 150 books and pamphlets were tracts for such causes as the education of blacks, workmen’s housing, and world peace. A moralistic novel, Ten Times One Is Ten (1871), inspired the organization of several young people’s groups. The reminiscent writings of his later years are rich and colourful: A New England Boyhood (1893), James Russell Lowell and His Friends (1899), and Memories of a Hundred Years (1902). His Works, in 10 volumes, appeared in 1898–1900. In 1903 he was named chaplain of the United States Senate. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-Everett-Hale accessed 10/19/2017

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Bethel, Missouri, 1854 - 1926, Rumford Falls, Maine

American, active 1813 - 1929

Paris, 1861 - 1930, New York

Chelsea, Massachusetts, 1852 - 1935, Yonkers, New York

Chilvers Coton, Warwickshire, 1819 - 1880, London

American, 1899 - 1969

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Hanover, New Hampshire, 1810 - 1888, Boston