Larz Anderson

Paris, 1866 - 1937, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia

After graduation, Anderson and a friend celebrated with a trip around the world. On his return to the United States, in the winter of 1889-1890 he worked briefly in the office of a New York East India trader before entering Harvard Law School. He had barely completed his first year there when one of his father's friends, Robert Todd Lincoln, the American minister to the Court of St. James, requested that young Anderson come to London and take the post of second secretary of the U.S. legation. As second secretary, Anderson assisted with the daily business of the legation. Handsome and impeccably mannered, he also was required to attend a dizzying array of social events and to mingle regularly with England's governing class and literati.

After Democrat Grover Cleveland became president in 1893, he named former secretary of state Thomas F. Bayard as the first U.S. ambassador to Great Britain and kept Anderson on as second secretary of the American embassy. A year later Anderson was posted to Rome as first secretary under Ambassador Wayne MacVeagh. In addition to his administrative and social functions, Anderson sought to bolster MacVeagh's effort to maintain good relations with Italy after a spate of lynchings of Italians in the state of Louisiana. In 1896, after a mob killed three Italians awaiting trial for murder in Holmesville, Louisiana, Anderson took part in delicate negotiations that led to the payment of a $6,000 indemnity to the Italian government. Following MacVeagh's resignation in early 1897, Anderson acted as chargé d'affaires at the American embassy for more than two months until the arrival of the new ambassador. Anderson then left immediately for home to marry Isabel Weld Perkins, who had inherited a fortune of $17 million from her maternal grandfather, William Fletcher Weld, a shipping magnate. The couple had no children.

In the spring of 1898 Anderson volunteered for service in the Spanish-American War. He turned down an army commission as major, which he believed inappropriate for one without prior military experience, and accepted the lower rank of captain. He was also made assistant adjutant general and ultimately acting adjutant general on the staff of General George W. Davis, commander of the Second Division of the Second Army Corps at Fort Alger, Virginia. After three months of intense training under difficult conditions, Anderson was demobilized when the war ended.

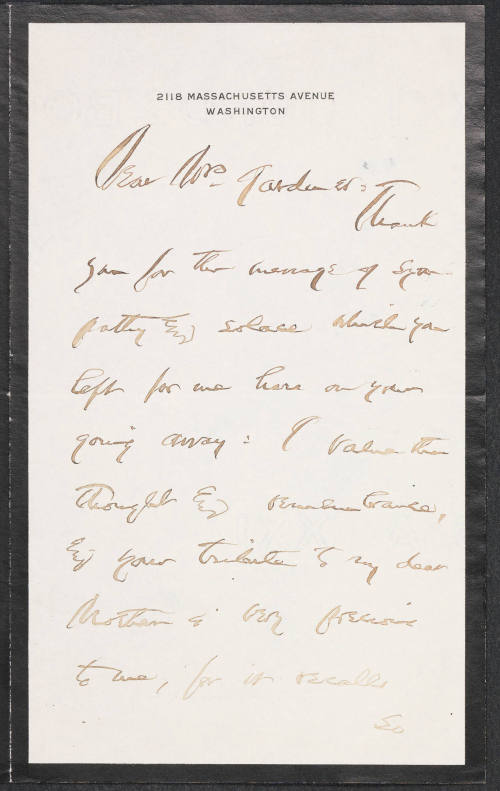

Anderson and his wife spent most of the rest of their lives traveling the world, attending the charity balls and formal dinners of high society in Boston and Washington, and hosting many events themselves at "Weld," their Brookline, Massachusetts, country house, where they summered, and at the Florentine villa they built at 2118 Massachusetts Avenue in the nation's capital, where they often spent their winters. In their travels they collected much valuable art for their homes and flora for their extensive gardens.

Anderson, who had contributed financially to the successful presidential campaign of William Howard Taft in 1908, commenced a brief return to the world of diplomacy in 1910. He and his wife accompanied Secretary of War Jacob McGavock Dickinson and General Clarence Edwards on an official tour of the Philippines that also took in China and Japan. In 1911 Taft offered Anderson a return to the foreign service as ambassador to Germany. Out of a personal disdain for German militarism and authoritarianism, Anderson turned down the post in Berlin and instead replaced Charles Page Bryan as minister to Belgium. In Brussels he utilized some of the many international contacts he had made over the years to convince the Belgian State Railways to end discrimination against American crude oil in violation of a Belgian-American tariff agreement.

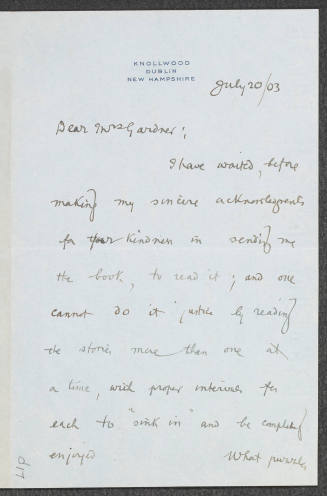

In the fall of 1912 Taft appointed Anderson ambassador to Japan. However, Taft's defeat by Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the presidential election caused Anderson's stay in Tokyo to end after only three months. Upon the change of administration, Anderson resigned and returned to his life of leisure, which was interrupted in 1914 by the coming of World War I. He soon immersed himself in relief activities in Washington and Boston. He served as honorary chairman of the New England Belgian Relief Committee and was a member and officer of the National Belgian Relief Committee, the New England Italian Relief Committee, and the Red Cross Council of the District of Columbia. His wife was even more heavily involved with relief chores, working in the Red Cross canteen in France and in hospitals on the Belgian and French fronts in 1917. The Anderson home in Washington became the Belgian mission in the United States, housed French officers, and was often given over for use by the Red Cross and the Belgian relief effort.

Beyond diplomacy and their energetic participation in the social scene, the Andersons were best known for their philanthropy. Phillips Exeter, Harvard, and Boston University were regular recipients of Anderson donations. Their largest single gift was a contribution of $200,000 to Harvard for the construction of the Nicholas Longworth Anderson Bridge connecting the university's Cambridge campus with its playing fields across the Charles River in Boston. The Andersons' Washington home ultimately became the headquarters of the national Society of the Cincinnati, and Weld, which garaged the Andersons' thirty-one cars (dating back to 1898), became an auto museum.

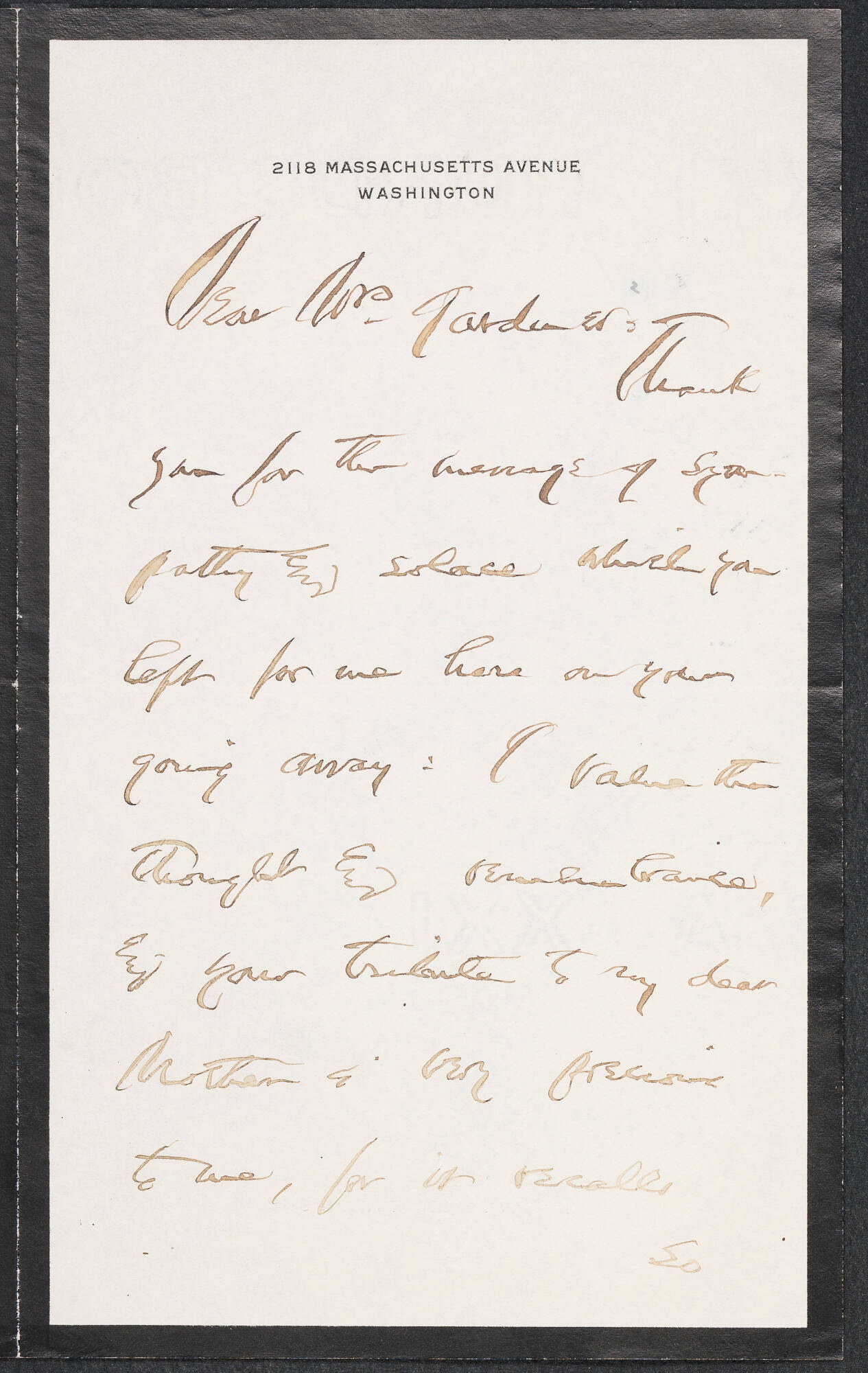

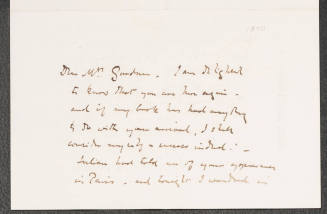

Anderson's personal papers, edited by his wife (an accomplished author of travel books and works for children) and published in 1940 as Larz Anderson: Letters and Journals of a Diplomat, are a chronicle of a bygone age of aristocratic pomp and diplomatic civility. Pleasant descriptions of balls, receptions, and hobnobbing with royalty in Europe and Japan take up most of the volume's pages. References to diplomatic intrigue and high politics are scarce. Though not a major figure of his generation, Anderson was charming, efficient, patriotic, and generous. His contemporary William Cameron Forbes characterized Anderson as "the finished and polished product of what was best in our civilization." Anderson died in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia.

Bibliography

In addition to Anderson's published letters and journals, short autobiographical articles can be found in the periodic Reports of the Harvard class of 1888. Anderson's communications with the State Department from Belgium are in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1912 (1919). The Quinquennial File in the Harvard University Archives has newspaper clippings on Anderson's life and career. Edgar Erskine Hume, Captain Larz Anderson, Minister to Belgium and Ambassador to Japan, 1866-1937 (1938), is a memoir reprinted by the Society of the Cincinnati of Virginia from its Minutes of 1937. Obituaries are in the Boston Herald and the New York Times, both 14 Apr. 1937.

Richard H. Gentile

Citation:

Richard H. Gentile. "Anderson, Larz";

http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00862.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:18:15 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Phoenixville, Pennsylvania, 1837 - 1934, Chicago

Rouen, France, 1869 - 1941, Le Cannet, France

Cincinnati, 1857 - 1930, Washington, D.C.

Fortress Monroe, Virginia, 1872 - 1948, Boston

Swanmore, England, 1869 - 1944, Toronto

at sea off the Cape of Good Hope, 1848 - 1914, London