George Grey Barnard

Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, 1863 - 1938, New York, New York

Upon his arrival in Paris in 1883 Barnard enrolled in the atelier of the academic sculptor Pierre-Jules Cavelier at the École des Beaux-Arts. He became a central figure in a group of American artists that consisted of sculptors George E. Bissell, Frederick MacMonnies, and Lorado Taft, and painter William Dodge. In 1886 Barnard met Alfred Corning Clark, an heir to the Singer Manufacturing Company fortunes, who immediately offered Barnard financial support. Barnard moved into spacious new quarters and withdrew from the École. A scholar of Norwegian mythology and a patron of the arts and opera, Clark bought or otherwise commissioned Barnard's first important work, Boy (1884) and Brotherly Love (1886-1887), both marble, and Norwegian Stove, a large porcelain relief begun in 1886 that illustrates the Nordic legend of the Creation. The most significant Clark purchase was Je sens deux hommes en moi, or The Two Natures of Man (1888-1894), a heroic marble group representing two nude male figures. Inspired by a line from Victor Hugo, the statue, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, allegorizes the popular fin de siècle theme of the conflicted soul. The Two Natures was exhibited and enthusiastically reviewed at the salon of the Champs de Mars in Paris in 1894. Admirers of Barnard's work, including the sculptor Auguste Rodin, compared him to the young Michelangelo.

Against the advice of Clark and his artist friends, who thought that the United States provided no creative freedom, Barnard returned to the United States in the summer of 1894 to wed Edna Monroe, the daughter of Lewis B. Monroe, the dean of the School of Oratory at Boston University. They settled in Washington Heights in upper Manhattan, where Barnard maintained a studio; the couple occasionally summered at the Monroe estate in Dublin, New Hampshire, the site of an art colony. They had three children. Barnard continued to work on small private commissions and on several large figurative pieces conceived in Paris, including The Hewer (1895-1902, marble), and The God Pan (1895-1898), which was originally intended for a fountain in New York's Central Park and is now owned by Columbia University. Barnard won a medal for The Two Natures at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo and for The God Pan at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. But a series of misunderstandings among Barnard, governing committees, and architectural supervisors denied him important public commissions. The quarrels isolated Barnard from his prospering Beaux-Arts colleagues, and the great success that Barnard had expected upon his return to the United States never materialized.

Around the turn of the century Barnard made the acquaintance of a loose-knit group of liberal writers, editors, academics, and performance artists. Through the Monroes, Barnard met dramatist-poet Percy W. MacKaye, who became his most lasting friend. Barnard also maintained longtime friendships with journalist Ida M. Tarbell, editor Albert Shaw, and editor-diplomat Walter H. Page. In the hopes of inspiring a patriotic ode to the United States, Isadora Duncan danced before Barnard in 1908. They hoped to produce a figurative tableau entitled "I See America Dancing."

The first of two large commissions that revived Barnard's career came in 1902. He was asked to create two large marble groups made up of nude figures to flank the staircase of the newly erected Capitol of Pennsylvania at Harrisburg. Separated into Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law and The Burden of Life: The Broken Law, the two groups dramatize the virtues of labor over special interest capitalism and celebrate progressive political views in the context of the Last Judgement. Work on the commission began in 1903 at Moret-sur-Loing near Fontainebleau, France, but the project was suspended in 1906, when charges of corruption encumbered Barnard's $300,000 portion of the building contract. Even though Barnard defaulted on specifications, a volunteer committee of receivers arose to handle Barnard's financial obligations and saw the project to completion. The works were first publicly displayed at the Paris Salon in 1910, where they were admired by Theodore Roosevelt. Once in place, they were dedicated at the Pennsylvania state capitol on 4 October 1911, which was officially declared "Barnard Day."

In 1911 Cincinnati philanthropist Charles P. Taft, brother of President William Howard Taft, commissioned Barnard to execute a statue of Abraham Lincoln. Completed in 1916, the statue was erected in Cincinnati in March 1917. The thirteen-foot-high bronze, which portrays Lincoln as a stooped, disheveled figure attired in wrinkled, ill-fitting clothes, was widely criticized for defaming America's greatest hero. Its detractors also noted that the uncouth, beardless Lincoln resembled a laborer more than a world-renowned statesman. When Charles Taft decided in 1917 to send duplicates of the statue to London's Parliament Square and to riot-torn Petrograd, Russia, a national outcry, led by Lincoln's son Robert Todd Lincoln, demanded that Woodrow Wilson's administration stop the shipment. The Russian project was suspended almost immediately; in 1919 the Lincoln statue designated for London was diverted to Manchester, England, while a duplicate of a more dignified Lincoln statue, previously made for the city of Chicago by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, was erected on the London site. A third copy of Barnard's Lincoln was privately commissioned in 1922 for Louisville, Kentucky.

Barnard's later years were consumed by speculative schemes that in their service to the broad theme of world peace combined sculpture with grandiose theatrical settings. His most extravagant plan envisioned the transformation of the northern end of Manhattan into a giant sculpture park akin to the Athenian Acropolis. As a starting point, Barnard completed work in 1933 on a plaster version of The Rainbow Arch. Like the Harrisburg stair groups, the arch divides sets of nude figures, representing refugees, into "good" and "bad" communities, each singly revealing the effects of peace and war. A journalist noted that when describing his concept, Barnard spoke with a "burst of lofty madness and consecration" (Pickering, Arts and Decoration, pp. 34-35).

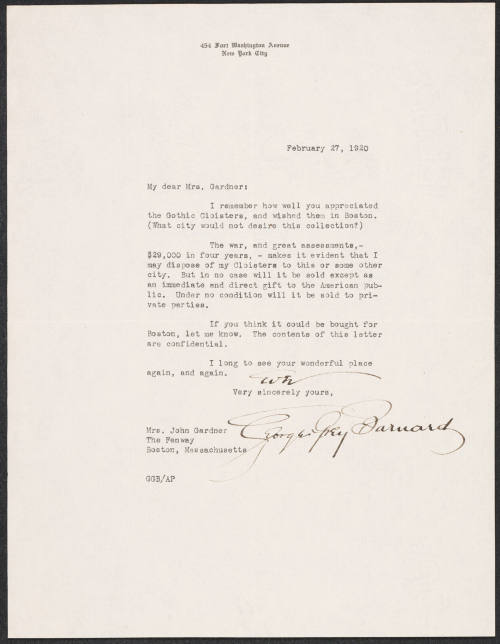

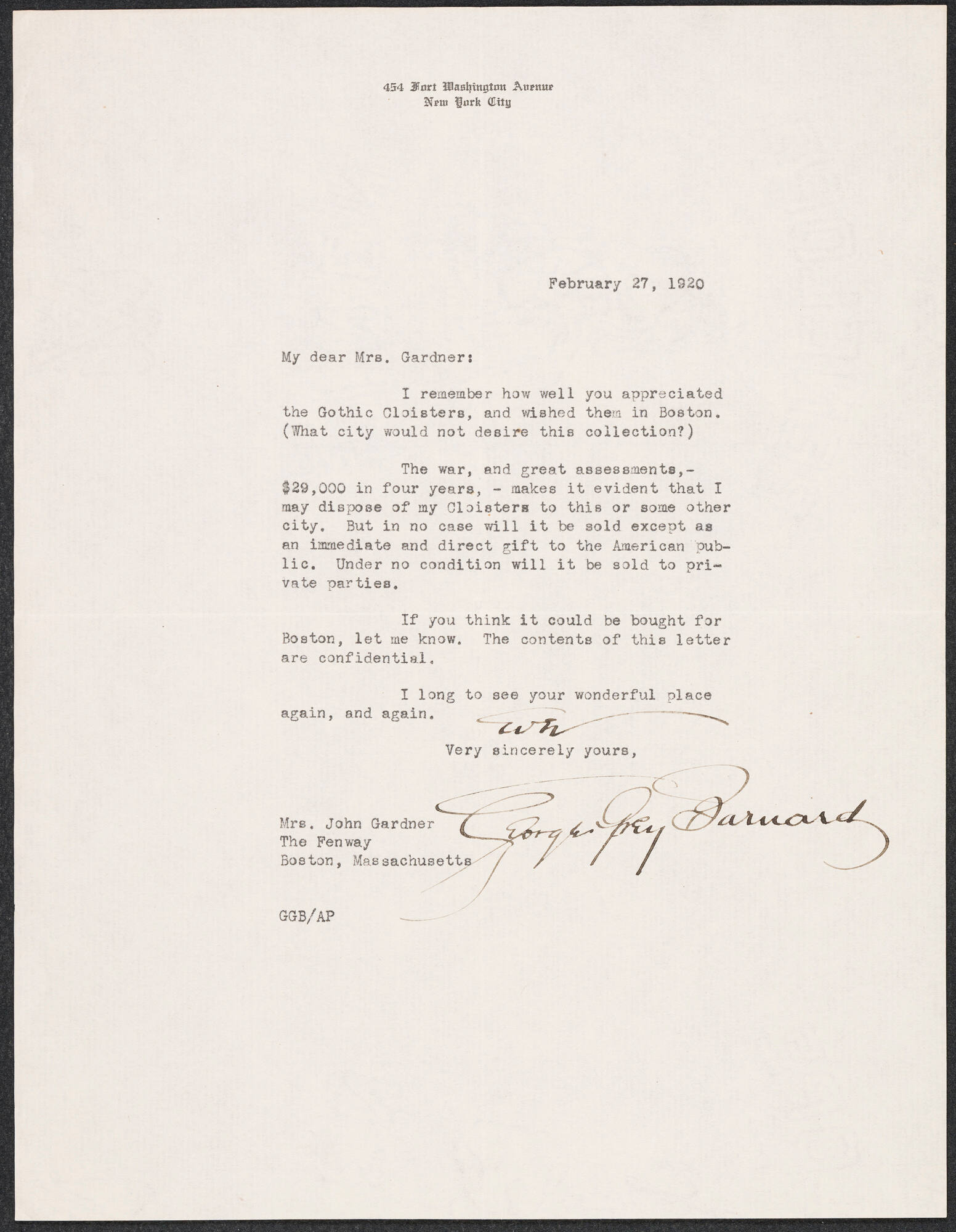

Barnard was also renowned as a collector of medieval art. While waiting out the Harrisburg fiasco in Moret, he began gathering and selling fragments of French Romanesque and Gothic monasteries, well in advance of the popular reappraisal of medieval art. The core pieces of Barnard's personal collection, including the cloisters of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, were installed in a brick structure known as the Cloisters, built next to Barnard's Washington Heights residence. The building was opened to the public in 1914 to benefit widows and orphans of French sculptors. In 1925 the contents were purchased by John D. Rockefeller and were deeded to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The treasures were then reassembled in the Cloisters Museum in Fort Tryon Park. Barnard thereupon began building and stocking a second museum, the Abbaye, whose contents eventually passed into the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Barnard had a powerful hold over many of his acquaintances. Marion MacKaye remembered the reaction of those who one evening heard him describe his discovery of a wax imprint of Michelangelo's thumb in the Sistine Chapel: Barnard's listeners were convinced that "he could be anything, make cities, anything; he is such a powerful, marvelous creator" (quoted in Ege). Despite his magnetic presence, Barnard's sculpture, with few exceptions, presents a cold and somewhat mechanical interpretation of the human form. In a time when the passionate creations of Rodin best summarized modern sensibilities, Barnard remained essentially a neoclassicist and a moralist. He died in New York City.

Bibliography

Barnard's papers are at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Bellefonte Historical Society in Bellefonte, Penn., the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg, and the Kankakee County Historical Society, Ill. The largest single collection of Barnard's work is at the George Grey Barnard Museum at the Kankakee County Historical Society.

For biographical information, see W. A. Coffin, "George Grey Barnard," Century Magazine 53 (1897): 877-82; Katherine Roof, "George Grey Barnard: The Spirit of the New World in Sculpture," Craftsman 15 (1908): 270-80; A. B. Thaw, "George Grey Barnard, Sculptor," World's Work 5 (1902-1903): 2837-53; and W. M. Van der Weyde, "Dramas in Stone: The Art of George Grey Barnard," Mentor 11 (Mar. 1923): 19-34. For evaluations of Barnard's work, see the following articles by Harold E. Dickson: "Barnard's Sculptures for the Pennsylvania Capitol," Art Quarterly 22, no. 2 (Summer 1959): 126-47; "Origin of the Cloisters," Art Quarterly 28, no. 4 (1965): 252-75; "The Other Orphan," American Art Journal 1 (Fall 1969): 109-15; "Log of a Masterpiece," Art Journal 20 (Spring 1961): 139-43; "George Grey Barnard's Controversial Lincoln," Art Journal 27 (Fall 1967): 8-15; and "Barnard and Norway," Art Bulletin 44 (Mar. 1962): 55-59. See also Ruth Pickering, "American Sculptor--George Grey Barnard," Arts and Decoration 42, no. 1 (Nov. 1934): 34-35, and Arvia M. Ege, The Power of the Impossible: The Life Story of Percy and Marion MacKaye (1992).

Frederick C. Moffatt

Citation:

Frederick C. Moffatt. "Barnard, George Grey";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00048.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:24:45 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

N.Y. collector; see catalog in library.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

1767 - 1818, Stowe, England

Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1890 - 1957, Big Sur, California

San Francisco, California, 1887 - 1981, Stamford, Connecticut

New York, 1876 - 1965, Dublin, New Hampshire

Exeter, New Hampshire, 1850 - 1931, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Paris, 1861 - 1930, New York