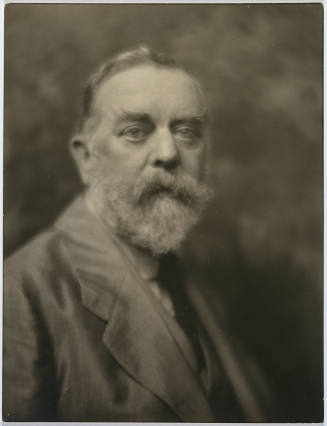

Percy Grainger

Victoria, Australia, 1882 - 1961, New York

By 1895 Grainger's pianistic accomplishments led him to pursue studies at the Hoch Conservatorium in Frankfurt am Main, where he learned from James Kwast and took theory and composition classes with Iwan Knorr. At the Hoch Conservatorium he fell in with several older British students—Cyril Scott, Henry Balfour Gardiner, Roger Quilter—who, with Norman O'Neill, were later dubbed the Frankfurt group. While in Frankfurt, Grainger fell under the spell of Rudyard Kipling, settings of whose verses he worked on between 1898 and 1956, and Walt Whitman, who inspired his Marching Song of Democracy (1901–15) and many aspects of his life philosophy.

From 1901 to 1914 Grainger based his career as a concert pianist and private teacher in London, whence he undertook frequent tours of northern Europe and two lengthy Antipodean visits in the touring party of the Australian contralto Ada Crossley (1903–4, 1908–9). During the first half of his residence in London, when often fulfilling subsidiary musical roles, Grainger depended upon sponsorship by such leading musicians as Hans Richter, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, and Sir Henry Wood. He also benefited from the patronage of such society figures as Sir Edgard and Lady Speyer, through whom he first met Edvard Grieg, and Lilith Lowrey, at whose ‘at homes’ in Chelsea Grainger was a particular favourite. Lowrey was so taken with the golden-haired Grainger that, in return for sexual favours and music lessons, she vigorously helped to promote his performing career. This ‘love-serve-job’, as Grainger termed it, ceased about 1904, when his mother felt it was no longer to his professional advantage. From 1910 onwards Grainger established himself more solidly in the virtuoso recitalist class and as performer of landmark Romantic concertos. He particularly promoted the piano concerto of Grieg, with whom he had studied the work in Norway during the composer's final months. Building on this new regard, Grainger finally relented in allowing his major compositions to be published, through Schott & Co., and in 1912 arranged the first London concert dedicated entirely to his compositions. Many of these early released and well-received works, such as Shepherd's Hey and Molly on the Shore, were based on English folk-songs, some of which Grainger himself had collected and edited in 1905–8. Others, such as Mock Morris and Handel in the Strand, were in a similarly jaunty style but were not direct settings of folk-songs. In 1911 he changed his name to Percy Aldridge Grainger.

With the outbreak of war in 1914 Grainger and his mother moved to New York. He took American citizenship in 1918, while serving in a US army band, and in 1921 settled in White Plains, New York, where he saw out his days. The years 1914–22 constituted the peak of Grainger's musical career. As a pianist he entered into lucrative piano-roll and gramophone recording contracts, and performed as a Steinway artist across the country with leading orchestras and conductors. In his concerts and recordings he played a wide variety of works from Bach to contemporary music, including lesser-known works by Stanford, Cyril Scott, Nathaniel Dett, and David Guion. In 1916 he undertook concerts with the soprano Nellie Melba, a compatriot, in aid of field ambulances, but did not avoid the accusation of his British friends that he was lurking in America to avoid his patriotic duty. Robin Legge, music critic of London's Daily Telegraph, charged Grainger with cowardice, and warned him that ‘England is no place for you after the war I fear’. During the war years his compositions, such as the In a Nutshell suite, the Marching Song of Democracy, and his ‘music to an imaginary ballet’ The Warriors, gained notable premières. His setting of a morris dance tune, Country Gardens, became an instant hit on its publication in 1919. Through dozens of arrangements, it remains his best-known work.

The suicide of his beloved mother in 1922, by leaping from a New York skyscraper, proved a watershed in Grainger's career. He became shy of the more challenging musical platforms and nostalgic for the simple enthusiasms of his youth. During 1922–8 he renewed his folk-song collecting expeditions; his work in Jutland with the Danish ethnologist Evald Tang Kristensen led to the composition of his Danish Folk-Music Suite. He undertook several visits to Europe, where he resuscitated his friendship with Frederick Delius, and to Australia, where he sought solace among his mother's relatives. During his return from one Australian trip, in 1926, he met the Swedish artist Ella Viola Ström-Brandelius (1889–1979), who on 9 August 1928, to the strains of his musical ‘ramble’ To a Nordic Princess, became his wife during one of his Hollywood Bowl appearances.

Although Grainger continued to perform for several decades after his marriage, he did so increasingly in an educational rather than fully professional role, preferring to trade appearances as a concerto soloist for performances of his own or his friends' new works. He relished the chance to perform in high-school auditoria, and during the Second World War saw his career as a solo pianist partially resurrected through numerous concerts at army and air force camps. Between 1919 and 1930 he taught in the summer school of the Chicago Musical College, and during 1937–44 at the National Music Camp, Interlochen. He gave his last official American concert tour in 1948, but continued, despite worsening health from 1952, to give occasional lectures and educational concerts until he was in his late seventies. Grainger died in White Plains Hospital, New York, on 20 February 1961. He was buried alongside his mother in the West Terrace cemetery, Adelaide, on 2 March 1961.

In 1911 Grainger concisely defined his enthusiasms in life as sex, race, athletics, speech, and art. In others' opinions, he was variously avant-garde, eccentric, or merely a poseur in these fields. He early realized the social utility of sex and over five decades enthusiastically practised flagellation with his wife, several earlier lovers, and by himself. ‘He was one of the century's more practised flagellants, equally at home in giving or receiving the lash’, having with the onset of puberty ‘started to associate the whipping with sexual pleasure, consequent upon acts of cruelty to women’ (All-Round Man, 9). Grainger was also obsessed with the idea of incest, considering it the most efficient way of maintaining racial purity.

On matters of race Grainger was an avowed proponent of Anglo-Saxonism and Nordicism, moving from a more racial intent in writings of the 1910s and 1920s to a more openly racist frame of mind in writings of the 1930s and early 1940s. He rejected all effete notions of the artist in favour of a muscular, open-air approach which he himself advertised through carrying of his own suitcases, long hikes, and vigorous on-stage antics. One of his most famed feats was to leap from the stage during the orchestral section of a concerto, run to the back of the hall, and return just in time to catch his next entry as soloist. His fascination with languages—he knew half a dozen to a reasonable level of competence—led to a quest to free the English language of Graeco-Latin contaminations supposedly introduced by the Normans in 1066. The resultant ‘blue-eyed’, or Nordic, English came to prominence from 1926 onwards in his voluminous autobiographical writings and his letters to friends. ‘Education’ became ‘mind-tilth’, ‘music’ became ‘tone-art’, and ‘telephone’ became ‘thor-juice-talker’.

It was, however, in Grainger's fifth field, that of art, that his ideas were most profound. Apart from keen promotion in his essays and musical editions of Nordic music, early music, percussion instruments, and the piano's more robust features, he lived his life in search of ‘free music’, desiring to float through musical space, unimpeded by ‘this absurd goose-stepping’ which he believed bedevilled music. Grainger likened music's contemporary condition to Egyptian bas-reliefs with their regularized shapes, while he yearned for the twists and curves of Greek sculptures. Early examples of Grainger's free experimentation include his Train Music (1900–01) and his Sea-Song (1907). His Random Round (1912–14), inspired by Pacific islander improvisatory practice, experimented with ‘concerted partial improvisation’, while his two ‘free music’ pieces of 1935–7 introduced the first consistently gliding tones in his output, achieved firstly by string quartet and then by a quartet of theremins.

In later life Grainger invented several ‘free music’ machines, with the intention of cutting out the role of the performer as interpreter of the composer's work. Rather, the composer would speak directly to the audience through the machine's exact reproduction of a work's features. The Estey-reed tone-tool (1950–51) was a form of giant harmonica, while the kangaroo-pouch tone-tool (1952) introduced a ‘hills and dales’ form of music which, to Grainger's mind, reflected Hogarth's ‘curve of beauty’. A further machine, the electric-eye tone-tool, incorporated photocells into its design, but remained incomplete at the composer's death.

As a composer Grainger was relatively prolific, producing over 400 works, either original compositions or folk-music settings. He was, however, most comfortable as a miniaturist: few of his works take more than seven or eight minutes to perform. Grainger's style was highly distinctive, almost baroque in its rhythm, with a ‘half-horizontal, half-perpendicular’ chordal sense, and an intertwining of parts owing much to Brahms. He considered himself a musical democrat, in both the way he wrote his music and the way he wanted it performed. In 1955 he professed to ‘like each voice, at all times throughout my music, to enjoy equal importance and prominence’ (Grainger on Music, 375). So, too, he sought through the ‘elastic scoring’ of many of his later compositions to establish simple groupings of instruments which would allow as many players as possible to take an effective part in the musical performance of his music. When asked late in life what his most important and characteristic works were, he listed nine works or collections, all but one of which he had started to compose by his mid-twenties. Among them were some fifty British folk-music settings, the orchestral English Dance (1901–9), and his two ‘Hillsongs’ (1901–7), inspired by a three-day hike in western Argyll (ibid., 374).

Grainger's legacy has been colourful. Among his five professed enthusiasms, his views on race are now considered abhorrent, while his attempts to reform the English language are taken as cranky, if not just bizarre. His sexual gusto has been kept well alive by occasional exposés in the Australian tabloid press, and sometimes linked with his notable athleticism. Late in life Grainger deposited a package with his bank that was to be opened ten years after his death: it held an essay and ‘a large collection of photographs giving full details of his sex life’ in the hope that ‘the world would be broadminded to accept such things without guilt or shame’ (Bird, 245). However, Max Harris in 1983 claimed Grainger as ‘one of the great embarrassments to the residual puritanism of the nation’ (The Unknown Great Australian, 1983, 58).

Within the realm of art, Grainger was a significant influence upon the emergence in the 1960s of a distinctively Australian art music, but more so in concept and theme than in actual style. While his band music, in particular Lincolnshire Posy (1937), was an important milestone in the development of American band repertory, his ‘free music’ experiments were rapidly overtaken by the development of electronic sound synthesis. Perhaps Grainger's most enduring legacy was in the setting of folk-music, where he was a popular model for following generations of British composers. Benjamin Britten, for instance, acknowledged Grainger as his ‘master’ in this regard. In 1934 Grainger established his own museum in the grounds of the University of Melbourne, where most of his papers, compositions, memorabilia, and recordings are housed.

Malcolm Gillies

Sources

J. Bird, Percy Grainger (1976) · K. Dreyfus, Music by Percy Aldridge Grainger (1978) · The farthest north of humanness: letters of Percy Grainger, 1901–14, ed. K. Dreyfus (1985) · W. Mellers, Percy Grainger (1992) · The all-round man: selected letters of Percy Grainger, 1914–61, ed. M. Gillies and D. Pear (1994) · Grainger on music, ed. M. Gillies and B. Clunies Ross (1999) · private information (2004) [family] · autopsy report, White Plains Hospital, New York · M. Gillies and D. Pear, Portrait of Percy Grainger (2002)

Archives

University of Melbourne, Grainger Museum, papers :: NL Scot., letters to D. C. Parker

SOUND

University of Melbourne, Grainger Museum, cylinder recordings, piano rolls, early gramophone recordings

Likenesses

R. Bunny, sketch, c.1902–1904, University of Melbourne, Grainger Museum · J. S. Sargent, chalk drawing, c.1907, University of Melbourne, Grainger Museum · Elliott & Fry, photograph, NPG [see illus.] · G. W. Lambert, double portrait, pencil drawing (with H. Tonks), NPG · J. S. Sargent, portrait, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne · photographs, University of Melbourne, Grainger Museum · photographs, Percy Grainger Library Society, White Plains, New York · photographs, Hult. Arch.

Wealth at death

£2725 6s.—in England: administration with will (limited), 18 Dec 1962, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Malcolm Gillies, ‘Grainger, Percy Aldridge (1882–1961)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/41081, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882–1961): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/41081

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

London, 1854 - 1933, Iford Manor, Westwood, Wiltshire

Bonn, Germany, 1770 - 1827, Vienna

Geisenheim, Germany, 1826 - 1890, Beverly, Massachusetts

Auburndale, Massachusetts, 1863 - 1919, Cedarhurst, New York

Votkinsk, Russia, 7 May 1840 - 6 November 1893, Saint Petersburg