Henry Cabot Lodge

Boston, 1850 - 1924, Boston

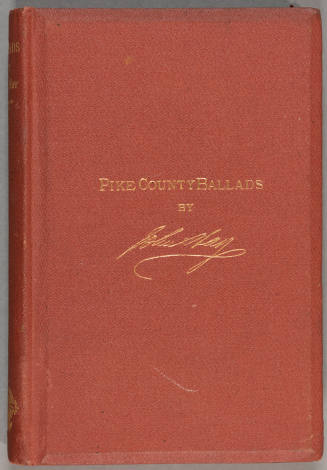

After a year-long honeymoon in Europe, Lodge, at the suggestion of Henry Adams, whose history course was one of the few he had done well in at Harvard, undertook a "historico-literary" career. He enrolled at Harvard Law School and at the same time studied German and Anglo-Saxon in preparation for taking Adams's graduate seminar in medieval history, first offered in 1873. He received his law degree in 1874 and a Ph.D., one of the first granted in history in the United States, in 1876. His dissertation on Anglo-Saxon land law was published in the Adams-edited Anglo-Saxon Law (1876). At the same time he served without pay as assistant editor of the North American Review, of which Adams was editor. In 1877 he began teaching a course in American colonial history at Harvard, and the next year he published the Life and Letters of George Cabot, his great-grandfather. He was soon turning out books and articles at a rapid pace, among them biographies of Alexander Hamilton (1882), Daniel Webster (1883), and George Washington (2 vols., 1889).

Lodge also, again at the suggestion of Henry Adams, became involved in politics. Like many eastern intellectuals, Adams was appalled by the sordid state of national politics in the Ulysses Grant era. He hoped to create a "party of the centre" in order to compel either the Democrats or the Republicans to substitute competitive civil service examinations for the spoils system. Lodge, however, discovering that few practical politicians would consider joining the Independent movement, voted (reluctantly) for the 1876 Republican presidential candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes.

In 1878 Lodge was elected to the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court as a Republican. Two years later he was a delegate to the Republican presidential convention, and in 1883 he managed the successful campaign of George D. Robinson for governor of Massachusetts. In 1884 he was again a delegate to the Republican National Convention, where the leading candidates were President Chester A. Arthur and James G. Blaine, a former secretary of state. Lodge disapproved of Arthur because he was a machine politician and Blaine because he considered him corrupt. When Blaine won the nomination, Lodge "could only rage impotently." Yet in the end he supported Blaine, thereby cementing his own position with Republican politicians but losing the respect of Independents and most of his upper-class Boston friends.

Lodge was a combative person who made enemies easily. When people he respected turned against him, he hid his resentment, but his apparent aloofness only made their anger more intense. "I have grown callous to the abuse & slander which have poured out on me," he recorded in his journal in 1890. Actually he was both deeply hurt and reinforced in his decision to stand by the Republican party. After 1884, when partisan issues were involved, he had something close to a closed mind.

Party loyalty won Lodge nomination to a seat in the House of Representatives in 1884. He was defeated, but two years later he ran again and won. In Congress he was assiduous in attending to the needs of his constituents, in participating in House debates, in working on committees, and in conducting an extensive political correspondence. He followed the Republican line on the protective tariff and most other matters but adopted a middle-of-the road position on the silver issue, favoring bimetallism rather than a single gold standard. He worked hard for the expansion of the civil service system and, being an author, for effective copyright legislation. In 1890 he took the lead in the fight for the Federal Elections (Force) Bill providing for federal supervision of elections in the South. The measure passed the House easily but was filibustered to death by southern senators. Lodge served in the House continuously until 1893, when he was elected to fill the seat of Senator Henry L. Dawes, who had retired.

In the Senate Lodge was basically conservative on domestic issues, but foreign affairs was his major interest. From early on his greatest ambition was to be chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He favored building a modern steel navy and what became known as the "large" policy. "We are dominant in this hemisphere," he boasted in a Senate speech (Cong. Rec. 53:3, pp. 3082-84). While not primarily interested in colonial expansion, he quickly adopted the ideas of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan about the value of sea power in advancing the national interest.

During the 1895 boundary dispute between Venezuela and Great Britain, Lodge supported President Grover Cleveland's threat to intervene, arguing that the British position was "a direct violation of the Monroe Doctrine." He favored the annexation of Hawaii and was an all-out supporter of the Spanish-American War and the annexation of Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Indeed, he would have preferred taking Cuba as well.

During the Progressive Era Lodge went along with most of President Theodore Roosevelt's (1858-1919) domestic initiatives. He did so partly because Roosevelt and he were close friends. But he also believed that moderate changes in government economic policy were necessary to prevent more drastic ones, such as government ownership of public utilities. And although rich by any standard, he had an aristocratic disdain for what were called in that day "robber barons," men, he wrote, who "pay no regard to the laws of the land or the laws and customs of society if the laws are in their way" (Early Memories, p. 217). He opposed, however, the progressives' efforts to make government more responsive to public opinion, such as the direct election of senators and the initiative, referendum, and recall.

Lodge was an enthusiastic supporter of Roosevelt's foreign policy. The maintenance of an "Open Door" policy in China and the construction of a canal across Central America received his hearty approval. In 1903 Roosevelt appointed him to the joint commission that determined the disputed boundary between Canada and Alaska on terms favorable to the United States. But he was mildly alarmed by some of Roosevelt's more radical domestic policies in the last year of his second term and was relieved when Roosevelt decided against seeking a third term.

In the controversies that developed between progressive Republicans and the Old Guard during the administration of William Howard Taft, Lodge tried to steer a middle course. He objected to the progressives' refusal to go along with party decisions, and he considered Taft an inept chief executive. For a time he hoped that Roosevelt would seek the Republican nomination in 1912 in order to preserve party unity. But after Roosevelt, moving further to the left, came out for the recall of state judicial decisions and, having failed to win the Republican nomination, ran on a Progressive party ticket, Lodge voted for Taft.

Lodge had a low opinion of Woodrow Wilson, who won the presidential election, chiefly because he believed that the formerly conservative Wilson had adopted progressive policies to win political favor. But Lodge was away from the capital a good deal during 1913 and early 1914 because of illness and played little part in the debates on the president's New Freedom domestic program. He supported Wilson's request for the repeal of a law exempting American vessels from tolls on ships passing through the Panama Canal, arguing that it was the president's prerogative to determine American foreign policy, and during the early stages of the Mexican revolution he did not object to Wilson's refusal to recognize the government of the dictator Victoriano Huerta. But he soon decided that the Wilson administration's handling of Mexican relations was "incompetent," the president himself alarmingly timid.

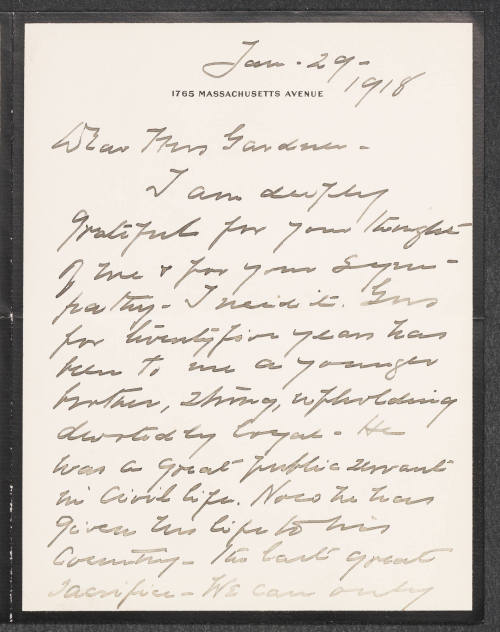

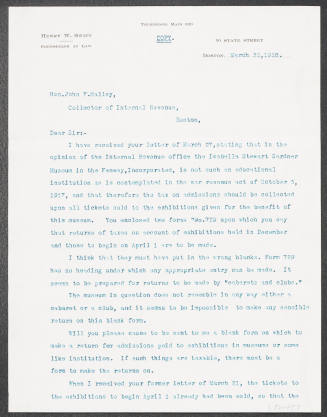

When war broke out in Europe in 1914, Lodge (like Wilson and nearly everyone in the United States) believed that the United States should maintain its neutrality, but he also believed that Germany was the aggressor and that Great Britain and France were fighting for freedom and democracy. In the fall of 1914 Wilson proposed relieving the war-induced shortage of shipping by purchasing German merchant vessels pinned in American ports by fear of Allied warships. Lodge took the lead in opposing the administration's Ship Purchase Bill in the Senate. "I had to sit there like a terrier at the mouth of a trap waiting for . . . the rat to come out," he explained (Lodge to Sturgis Bigelow, 9 Mar. 1915, Lodge papers). He denounced Wilson as pro-German, his argument being that the ships were currently useless to the Germans and that since the Allies would not recognize the transfer of title, war might result if they seized or fired upon the vessels on the high seas. After months of debate, the bill was defeated.

The president's reluctance to strengthen the armed forces further angered Lodge, who by 1915 was convinced that a German victory would threaten American security. So did Wilson's failure to take strong action against Germany after a U-boat sank the British liner Lusitania without warning in May 1915. The president's insistence that both sides were violating America's rights as a neutral and his call for a "peace without victory" in early 1917 appalled Lodge.

When Wilson finally asked Congress to declare war in April 1917, as he put it, to make the world safe for democracy, Lodge praised his decision. He commented privately, however, that if that decision was correct, "everything [Wilson] has done for two years and a half is fundamentally wrong" (to Roosevelt, 23 Apr. 1917, Lodge papers). He also supported most of the administration's war policies. But he favored demanding the unconditional surrender of the Central Powers, and, like all Republican politicians, he resented deeply Wilson's 1918 "Appeal" unsuccessfully asking voters who "have approved of my leadership" to elect Democratic majorities to both houses of Congress.

Lodge approved of many of the terms negotiated by Wilson at the Paris Peace Conference, including the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France and the principle of self-determination in Central Europe. He also had no objection to the creation of some kind of international organization, but he thought the League of Nations as described in the peace treaty that Wilson negotiated "loose, involved, and full of dangers." By this time his dislike of Wilson had turned to hatred. This certainly influenced his attitude toward the league, as did his partisan wish to prevent the Democrats from converting the popular enthusiasm for peace into victory in the 1920 presidential election. But above all he believed that the league charter required sacrifices of national sovereignty that he (and in his opinion the Senate and most citizens) would not support. He insisted that Article X of the covenant, guaranteeing the territorial integrity of all members, usurped the constitutional power of Congress to declare war. "We are asked," Lodge told the Senate, "[to] subject our own will to the will of other nations. . . . That guarantee we must maintain at any cost when our word is once given" (Cong. Rec. 65:3, pp. 4520-28).

When the Versailles Treaty came before the Senate, Lodge, now chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, drafted fourteen "reservations" to the league covenant. Some were designed for purely political purposes, and others were probably unnecessary. By far the most important stated that Article X should not apply "unless in any particular case the Congress . . . shall by act or joint resolution so provide."

A solid majority of the Senate, far more than the one-third needed to prevent ratification of the treaty, was committed to this position. Yet the president, who had suffered a severe stroke while the treaty was before the Senate, refused to accept the Lodge reservations or to make any compromise whatsoever. "Let Lodge compromise," he told Senate minority leader Gilbert Hitchcock. With Wilson adamant and Lodge and most of the Republican senators unwilling to accept the league as it was, the Versailles Treaty was rejected on 19 November 1919, thirty-five ayes to fifty-five nays. A second vote the following March produced a majority (but not the required two-thirds) for the league with Lodge's reservations.

The 1920 election was a sweeping Republican victory, but Lodge's role in the defeat of the League of Nations hurt him badly when he ran for a seventh term in the Senate two years later. He won reelection by a mere 7,000 votes in a total of nearly 900,000. Thereafter the Massachusetts Republican party was dominated by the supporters of Vice President (later President) Calvin Coolidge.

Lodge's last important public service was as a delegate to the Washington Disarmament Conference, the ratification of which he shepherded through the Senate successfully in March 1922. He died in Boston after a prostate operation.

Lodge was in many ways a model legislator. He was fiercely patriotic and devoted to public service. During his long career he spoke out clearly on public issues, worked hard at committee assignments, and attended assiduously to the legitimate requests of his constituents. He scrupulously avoided conflict-of-interest situations, always disposing in advance of stock and other assets that might be affected by legislation under discussion. Both his intelligence and his knowledge of politics were of a high order.

His weaknesses were primarily temperamental. The reaction of his set to his support of Blaine in 1884 seems at this distance to have been unjustified--Blaine for all his faults was a valuable public servant and far more creative than most of the leading men of the period. But the enduring bitterness, the cynicism, and the extreme partisanship that the episode inspired in Lodge are reflections of his haughty and combative nature. He lacked the warmheartedness of his even-more-combative friend Theodore Roosevelt, and this goes far toward explaining why he was so widely unloved.

Bibliography

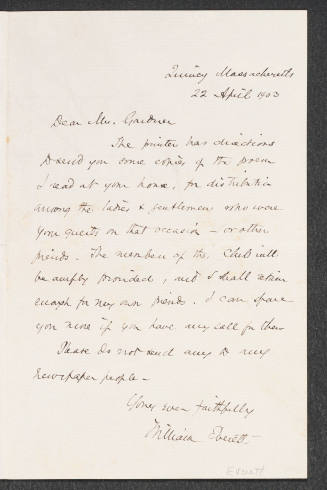

The Lodge papers are in the Massachusetts Historical Society. They contain masses of political and family letters and other material, including Lodge's journals and scrapbooks, and the manuscripts of many of his books and articles. The society also houses the papers of many of Lodge's contemporaries, as does the Library of Congress, where the most useful collection is the Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Lodge's autobiography, Early Memories (1913), is an essential source for his early life and shows Lodge's personality at its best. His The Senate and the League of Nations (1925) is useful but biased. (Lodge insists in it that he had no personal hostility toward Wilson.) Lodge edited Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge (2 vols., 1925), but this work must be used with caution because he altered many of the letters. The most complete biography is John A. Garraty, Henry Cabot Lodge (1953), but the fullest discussion of Lodge's ideas about foreign policy, and the most up-to-date listing of Lodge's published works, is in William C. Widenor, Henry Cabot Lodge and the Search for an American Foreign Policy (1980).

John A. Garraty

Back to the top

Citation:

John A. Garraty. "Lodge, Henry Cabot";

http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00442.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 16:28:18 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Manchester, New Hampshire, 1879 - 1968, West Harwich, Massachusetts

Cincinnati, 1857 - 1930, Washington, D.C.

Blackburn, England, 1838 - 1923, Wimbledon, England

Watertown, Massachusetts, 1839 - 1910, Quincy, Massachusetts

Salem, Indiana, 1838 - 1905, Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire