Edward Charles Pickering

Boston, 1846 - 1919, Cambridge, Massachusetts

After spending two years teaching mathematics at his alma mater, Pickering was appointed assistant professor of physics at the newly founded Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1867. There, he established the first physics laboratory in the United States that was specifically designed for student instruction. He later compiled and published the experiments that he devised for his students in Elements of Physical Manipulation (1873-1876), the first American laboratory manual of physics. In 1874 he married Lizzie Sparks, the daughter of Jared Sparks, a noted historian and former Harvard president; they had no children.

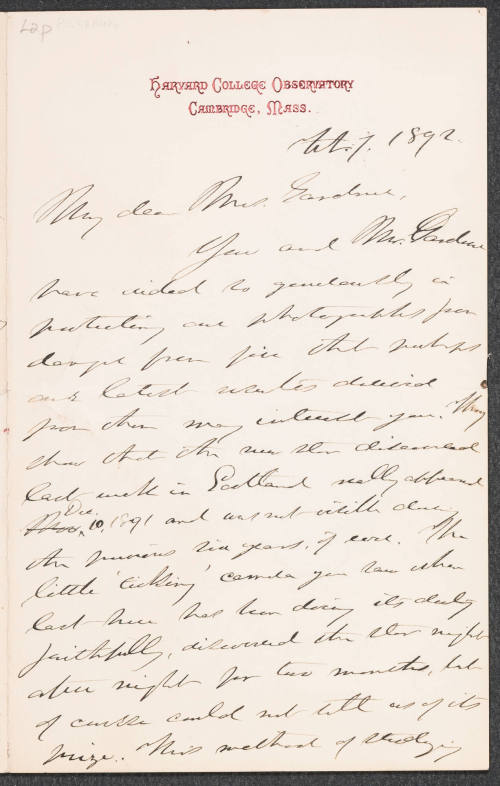

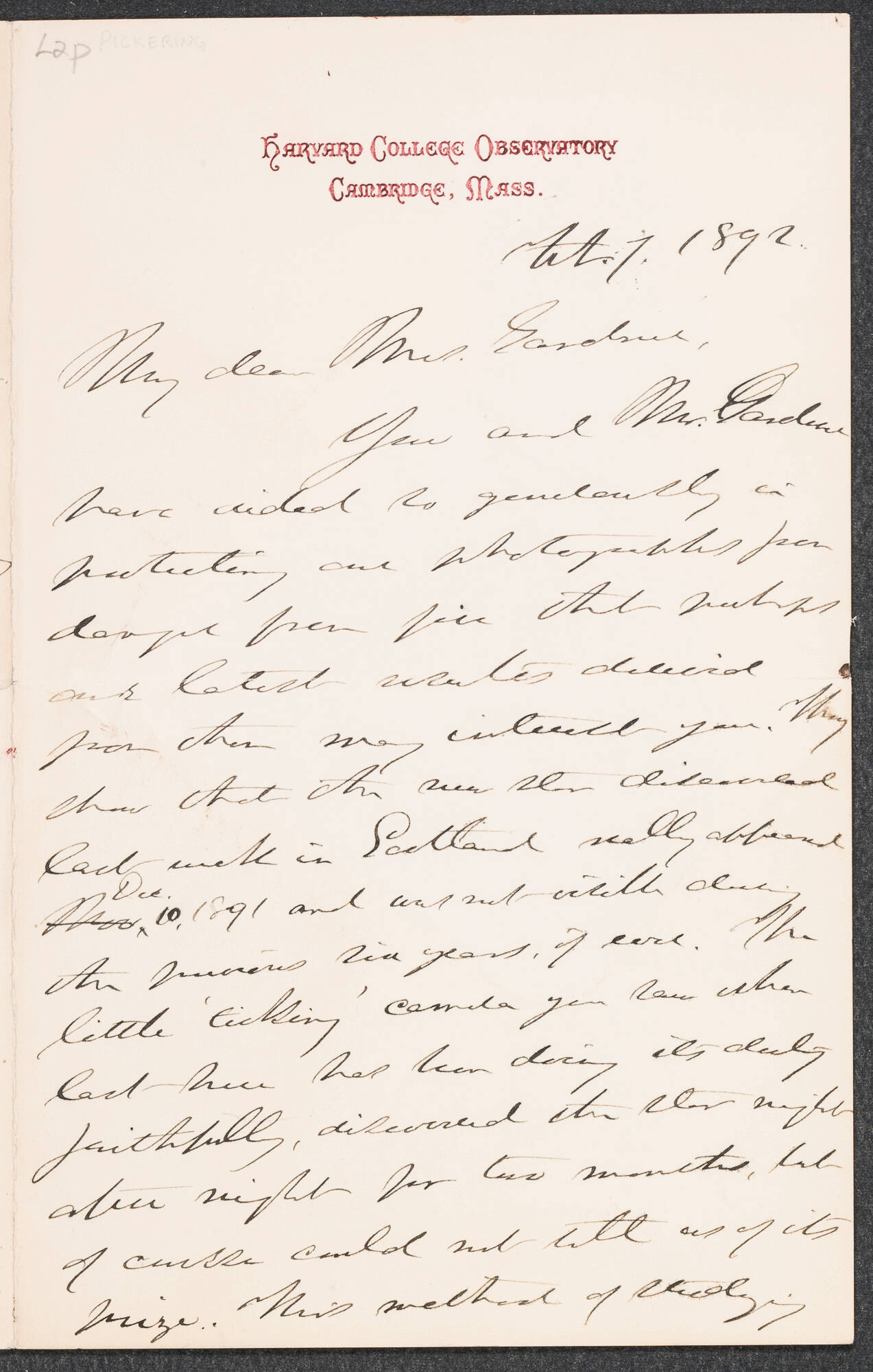

In 1877 Pickering became director of the Harvard College Observatory, a position that he held until his death. From the beginning of his directorship, Pickering decided to devote the observatory's research program to the new field of astrophysics rather than to the classical astronomy of position and motion.

In order to measure the magnitudes of the stars, Pickering (working in close cooperation with George B. Clark) invented a new class of photometers. With one of these, a 4-inch meridian photometer, he measured the brightnesses of about 60,000 stars of ninth magnitude or brighter between 1882 and 1902. This work culminated in the publication of Revised Harvard Photometry (1908), which remained the standard reference until photographic methods largely supplanted visual ones.

From as early as 1883 Pickering expressed a desire to use photography to chart the heavens. The creation of an International Astrographic Congress in 1887 to cooperate in a joint photographic map, however, drew his plan to a temporary halt. Becoming frustrated by the slow progress of the participating observatories, he decided to produce his own map. Using photographic doublets, a type of telescopic camera, of 2.5-inch aperture, he issued a Photographic Map of the Entire Sky on fifty-five glass plates in 1903. This was the first such map ever published. From 1885 on he routinely photographed a large portion of the visible sky on every clear night, which resulted in a collection of some 300,000 glass plates that became known as the Harvard Photographic Library. This photographic history of the heavens was not duplicated anywhere else and has been heavily relied on by astronomers throughout the world.

Spectroscopy, the analysis of the chemical composition and physical condition of stars, was another of Pickering's early interests. Research in this area intensified greatly in 1886 because of the establishment of the Henry Draper Fund, named for the pioneering astrophysicist Henry Draper. Under the terms of this fund, Draper's wife, Mary Anna Palmer Draper, supplied Pickering with money to photograph and classify stellar spectra and to publish the results in a catalog as a memorial to her late husband. In the first Henry Draper Memorial publication, The Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra (1890), more than 10,000 stars were assigned spectral classes by Williamina P. Fleming, curator of astronomical photographs at Harvard.

Pickering's establishment of a southern hemisphere observatory in Arequipa, Peru, in 1891 and Mrs. Mary Anna Draper's continuing financial support allowed Pickering to extend his work to the South Celestial Pole. As a result, he was able to complete the first pole-to-pole spectroscopic study of the heavens ever undertaken by a single institution.

These spectroscopic investigations culminated in the publication of The Henry Draper Catalogue (1918-1924), in which nearly a quarter-million stellar spectra were measured by astronomer Annie Jump Cannon and placed into one of twelve main spectral classes in a system that had first been devised by Fleming. The Fleming-Cannon system--usually referred to inaccurately as the Draper classification system--was adopted for worldwide use in 1913 at the Bonn meeting of the International Union for Cooperation in Solar Research.

Pickering made two other important contributions to the field of stellar spectroscopy. In 1886 he discovered a series of spectral lines in a star, which he thought represented hydrogen under some unknown conditions of temperature or pressure; later, Danish physicist Niels Bohr showed them to be actually due to ionized helium. In 1889 he discovered the first spectroscopic binary--a double star that can be detected as such only by the periodic doubling of its spectral lines.

Pickering was elected president of the American Astronomical Society in 1905, a position to which he was annually reelected until his death. During this period, he hoped to secure a multimillion-dollar fund from which he could distribute grants to both American and international astronomers to support their research. In a separate effort, he hoped to secure funds to establish an internationally administered 84-inch telescope in the southern hemisphere. For neither plan, however, did he succeed at winning support.

In his later years, one of Pickering's chief interests was in the field of photographic photometry. In 1907 he announced plans to determine the photographic magnitudes of a sequence of stars near the North Celestial Pole, which would serve as a standard system of stellar photographic magnitudes. The work, which was carried out by Henrietta Swan Leavitt and published as The North Polar Sequence (1917), provided a system that, like the Fleming-Cannon classification system, was adopted for worldwide use by the Solar Union.

After forty-two years as Harvard College Observatory director, Pickering died in Cambridge. There was virtually no astronomer active during this period who did not benefit from his keen interest and generous assistance. Through his own research and that of his staff, he helped to establish the science of astrophysics and to propel Harvard into a position of world leadership in that area.

Bibliography

Pickering's papers--sixty-eight linear feet of personal and official correspondence, notebooks, and scrapbooks--are in the Harvard University Archives. An extensive listing of his writings is appended to Solon I. Bailey, "Biographical Memoir of Edward Charles Pickering," National Academy of Sciences, Biographical Memoirs 15 (1934): 169-78. For general histories of the Harvard Observatory, see Bailey, The History and Work of Harvard Observatory, 1839 to 1927 (1931); Bessie Zaban Jones and Lyle Gifford Boyd, The Harvard College Observatory: The First Four Directorships, 1839-1919 (1971); and Howard Plotkin, "Harvard College Observatory's Boyden Station in Peru: Origin and Formative Years, 1879-1898," Mundialización de la ciencia y cultura nacional. Actas del Congreso Internacional "Ciencia, descubrimiento y mundo colonial" (1993). For more specific treatments of Pickering, see Plotkin, "Edward C. Pickering," Journal for the History of Astronomy 21 (1990): 47-58; Plotkin, "Edward C. Pickering, the Henry Draper Memorial, and the Beginnings of Astrophysics in America," Annals of Science 35 (1978): 365-77; Dorrit Hoffleit, "The Evolution of the Henry Draper Memorial," Vistas in Astronomy 34 (1991): 107-62; and Plotkin, "Edward C. Pickering and the Endowment of Scientific Research in America, 1877-1918," Isis 69 (1978): 44-57.

Howard Plotkin

Back to the top

Citation:

Howard Plotkin. "Pickering, Edward Charles";

http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-01309.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 12:34:33 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Boston, 1855 - 1916, Flagstaff, Arizona

Salem, Massachusetts, 1745 - 1829, Salem, Massachusetts

active London, 1858 - 1878

Boston, 1842 - 1921, Boston

Black Bourton, England, 1768 - 1849, Edgeworthstown, Ireland

Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, 1863 - 1938, New York, New York