Percival Lowell

Boston, 1855 - 1916, Flagstaff, Arizona

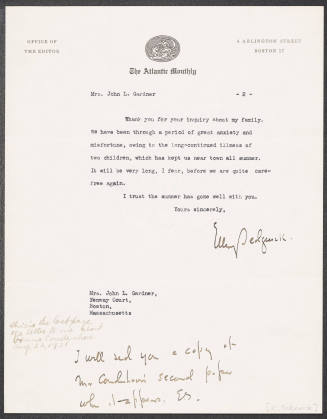

Lowell graduated from Harvard in 1876 with distinction in mathematics. He then took the customary grand tour of Europe, though he traveled farther than most--all the way to Syria. He then returned to Boston and settled down to work in the office of his grandfather, John Amory Lowell, handling finances for cotton mills and for a time serving as executive head of a large cotton mill. Shrewd investments soon freed Lowell from the daily tedium of business. Lowell traveled to the Far East several times and was so well received that he was appointed foreign secretary and counselor for a special Korean diplomatic mission to the United States in 1883 (Korea could not afford to carry out the task). He wrote articles for the Atlantic Monthly and four books about the region, one of which (The Soul of the Far East [1888]) may have helped persuade Lafcadio Hearn to go to Japan.

Lowell was deeply interested in astronomy; his Harvard commencement speech had been on the nebular hypothesis, explaining the origin of the solar system, and he sometimes took a telescope on his travels. One story has Lowell learning in 1893, while returning from Japan, that the eyesight of the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, observer of "canali" on Mars, was failing. Lowell, his eyesight the keenest a leading ophthalmologist had ever examined, now supposedly decided that it was his manifest destiny to continue Schiaparelli's work. (Schiaparelli's eyesight was deteriorating, but he may not have realized it; neither, consequently, would Lowell have known about the deterioration until years later.)

In 1894 Lowell established an observatory at Flagstaff in the Arizona Territory and began searching for signs of intelligent life on Mars. In 1895 he published his controversial hypothesis in a series of articles in the Atlantic Monthly and in the book Mars. From visible changes, including changes in the polar cap and seasonal changes in the tint of dark areas, Lowell concluded that Mars had both an atmosphere and water and thus could support life. Seemingly there were signs of actual inhabitants: an apparent irrigation system of straight canals (visible to Lowell and some others but not to all observers) radiating from central points. For Lowell it was enough that the theory might be true, but professional scientists envisioned alternative explanations and returned a verdict of "not proven." Furthermore, scientists were expected to observe first and theorize secondly, if at all. William Wallace Campbell at the Lick Observatory objected that "Mr. Lowell went direct from the lecture hall to his observatory, and how well his observations established his pre-observational views is told in his book."

Scientists generally responded negatively to Lowell's work, but many readers responded enthusiastically to his entertaining and informative prose. For example, he described Mars as "a great red star that rises at sunset through the haze about the eastern horizon, and then, mounting higher with the deepening night, blazes forth against the dark background of space with a splendor that outshines Sirius and rivals the giant Jupiter himself." Lowell was a poet turned physicist applying his New England intellectual heritage to science. Emphasizing that something was possible rather than that it was not proved, legitimizing inferences, and intelligently anticipating new developments, he replaced sane but unsensational astronomy with more imaginative thought. Furthermore, Lowell had taken the popular side of the most popular question afloat. Tenantless globes would be an affront to the sense of the rational in creation, while the discovery of intelligent life on other planets would increase reverence for the Creator. There would also be enlightening social results because cooperation was seemingly a distinctive feature of life on Mars, where the civilization did not have wars. Mars and its inhabitants had perhaps developed earlier and thus further than had humans on earth, in accord with Darwinian theory. Mars revealed the future of the earth, with an advanced science and technology and also an ebbing of life-sustaining resources.

Lowell's purported observation of canals on Mars is now thoroughly discredited. Partly the product of a psychological inclination to connect minute details too small to be separately and distinctly defined, it is also an instance of preconception influencing observation. In his obituary of Lowell, the Princeton astronomer Henry Norris Russell warned that "if the observer knows in advance what to expect . . . his judgment of the facts before his eyes will be warped by this knowledge, no matter how faithfully he may try to clear his mind of all prejudice. The preconceived opinion unconsciously, whether he will or not, influences the very report of his senses."

Nervous exhaustion slowed Lowell's pace for several years, but by 1901 he was back observing. He also gave two series of popular lectures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in 1902 on the solar system and in 1909 on the evolution of worlds, and a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute in 1906 on Mars as the abode of life. All three series were published in book form, and the 1906 lectures also appeared in the Century Magazine. Lowell married Constance Savage Keith, a long-time Boston neighbor, in 1908; they had no children.

To explain the origin of the solar system, Lowell in his 1908 Mars as the Abode of Life chose Pierre-Simon Laplace's older nebular hypothesis (in which rings of gas shed by the contracting sun condensed to form planets) over its new rival, the Chamberlin-Moulton hypothesis (in which the solar system was formed by a collision between a small nebula and the periphery of a large nebula). Eliot Blackwelder, professor of geology at the University of Wisconsin (where Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin had been president), characterized Lowell's book as fancy foisted upon a trusting public. Misbranding intellectual products was as immoral as misbranding manufactured products, and "censure can hardly be too severe upon a man who so unscrupulously deceives the educated public, merely in order to gain a certain notoriety and a brief, but undeserved, credence for his pet theories." The quarrel escalated in an entertaining if unseemly manner, with Forest Ray Moulton calling Lowell "that mysterious 'watcher of the stars' whose scientific theories, like Poe [Edgar Allan Poe]'s vision of the raven, 'have taken shape at midnight.' "

In his 1902 lectures on the solar system, Lowell had casually predicted the existence and eventual detection of another planet. He began searching for it in 1905, directing assistants at Flagstaff to take sets of photographs, each set of the same region of the sky but at different times, and then to compare photographs within each set, looking for objects that had changed position over time. Stars show no such movement, but a planet does, as do comets and asteroids, which Lowell Observatory astronomers found in abundance. But no new planet was detected. In 1908 Lowell plunged vigorously into mathematical calculations of the position of a trans-Neptunian planet from perturbations in Uranus's motion, and followed up with a systematic photographic search of regions of the sky suggested by his several solutions to the mathematical problem. But his death in Flagstaff (at the observatory) preceded success.

Lowell left more than $1 million in trust for the observatory to ensure continuation of his work, but his widow instituted litigation that dragged on for more than a decade. Planning for an expensive new photographic telescope and for another search for Planet X began in 1927, the search itself began in 1929, and by March 1930 the planet was found. Continuing the tradition of naming planets for Roman gods, Vesto M. Slipher, the director of the observatory, chose the name Pluto, god of the regions of darkness, and , Percival Lowell's superposed initials, for the planetary symbol. The remarkable resemblance between Pluto's orbit and Lowell's prediction probably is a coincidence, since Pluto's mass is now known to be too small to have caused the perturbations in Uranus's orbit used by Lowell to calculate Pluto's position.

Little of Lowell's scientific work has survived history's cruel critique. Yet his scientific bequest--the distinguished and continuing efforts of many astronomers at the Lowell Observatory, which he founded and funded--is as formidable as his family heritage.

Bibliography

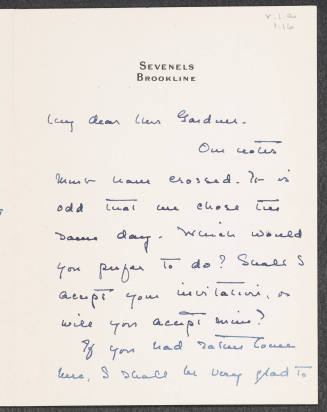

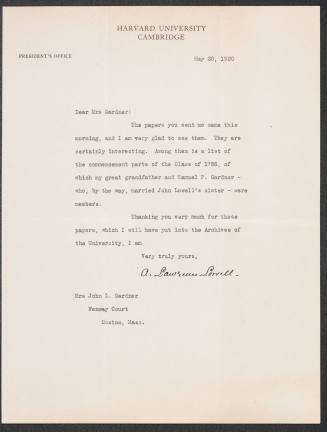

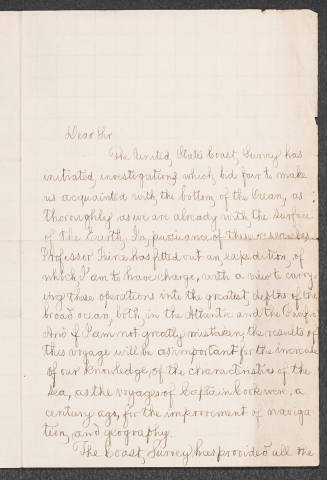

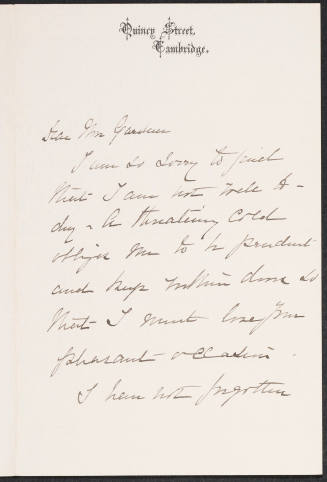

Documentary material on Lowell's scientific life, including correspondence, drafts and texts of articles, and newspaper clippings, is preserved at the Lowell Observatory. The letters are available in a microfilm edition, The Early Correspondence of the Lowell Observatory 1894-1916 (1973). Lowell's books not mentioned in the text are Chosön, the Land of the Morning Calm: A Sketch of Korea (1886); Noto: An Unexplored Corner of Japan (1891); Occult Japan; or, The Way of the Gods: An Esoteric Study of Japanese Personality and Possession (1894); The Solar System: Six Lectures at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in December, 1902 (1903); Mars and Its Canals (1906); and The Evolution of Worlds (1909). His scientific reports appeared primarily in publications of his observatory: Annals of the Lowell Observatory, Lowell Observatory Bulletins, and Memoirs of the Lowell Observatory. A biography, with many excerpts from Lowell's writings but little insight into his character, was compiled by his brother, A. Lawrence Lowell, Biography of Percival Lowell (1935). Quotations from his letters, chosen by his long-time secretary to display his personality and varying moods, are presented in Louise Leonard, Percival Lowell: An Afterglow (1921). A thorough command of archival material at the Lowell Observatory is evident in the excellent depictions of Lowell's work by William Graves Hoyt, Lowell and Mars (1976) and Planets X and Pluto (1980). The crucial role of the Harvard College Observatory in the founding of the Lowell Observatory, revealed in the correspondence in the Harvard University Archives, is detailed by David Strauss, "Percival Lowell, W. H. Pickering and the Founding of the Lowell Observatory," Annals of Science 51 (Jan.-Feb. 1994): 37-58. A sketch of his life appears in Ferris Greenslet, The Lowells and Their Seven Worlds (1946).

On the debate over life on Mars, see Michael J. Crowe, The Extraterrestrial Life Debate 1750-1900: The Idea of Plurality of Worlds from Kant to Lowell (1986), in particular chapter 10. Lowell's observations of Mars are examined in chapter 5 of Norriss S. Hetherington, Science and Objectivity: Episodes in the History of Astronomy (1988). Other aspects of Lowell's work are examined in Hetherington, "Lowell's Theory of Life on Mars," Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflet 501 (Mar. 1971): 1-8; and "Percival Lowell: Professional Scientist or Interloper?" Journal of the History of Ideas 42 (1981): 159-61. Related topics are discussed in George E. Webb, "The Planet Mars and Science in Victorian America," Journal of American Culture 3 (1980): 573-80, and in Hetherington, "Amateur versus Professional: The British Astronomical Association and the Controversy over Canals on Mars," Journal of the British Astronomical Association 86 (1976): 303-8. On Lowell's study of East Asia, see David Strauss, "The 'Far East' in the American Mind, 1883-1894: Percival Lowell's Decisive Impact," Journal of American-East Asian Relations 2 (Fall 1993): 217-41.

Citation:

Norriss S. Hetherington. "Lowell, Percival";

http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-01024.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Jun 13 2014 11:08:38 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Portland, Maine, 1838 - 1925, Salem, Massachusetts

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1819 - 1891, Cambridge, Massachusetts

New York, 1872 - 1960, Washington, D.C.

New York, 1862 - 1933, Poughkeepsie, New York

Brookline, Massachusetts, 1874 - 1925, Brookline, Massachusetts

Francestown, New Hampshire, 1825 - 1896, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Boston, 1822 - 1907, Arlington, Massachusetts

Boston, 1841 - 1935, Washington, D.C.