Ellery Sedgwick

New York, 1872 - 1960, Washington, D.C.

In 1900 Sedgwick moved to Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, a national circulation leader, as editor. Here, from 1900 to 1906 Sedgwick began to develop his reputation as a discerning editor with an eye for wit, erudition, and humor. He published Stephen Crane, H. L. Mencken, and the feminist satirist Marietta Holley, as well as Sewell Ford, novelist and short-story writer; Samuel Merwin, a writer of popular fiction; and Frank R. Stockton, known for his 1882 short story "The Lady or the Tiger?"

Under Sedgwick the magazine (renamed Leslie's Monthly in 1904, the American Illustrated Magazine in 1905, and later that year, the American) offered distinguished coverage of public affairs. Although Leslie's was not really a muckraker like so many of its contemporaries, historian Louis Filler cites Sedgwick's significant impact on government legislation through his prominent publicizing of railroad safety violations in Leslie's pages in 1903.

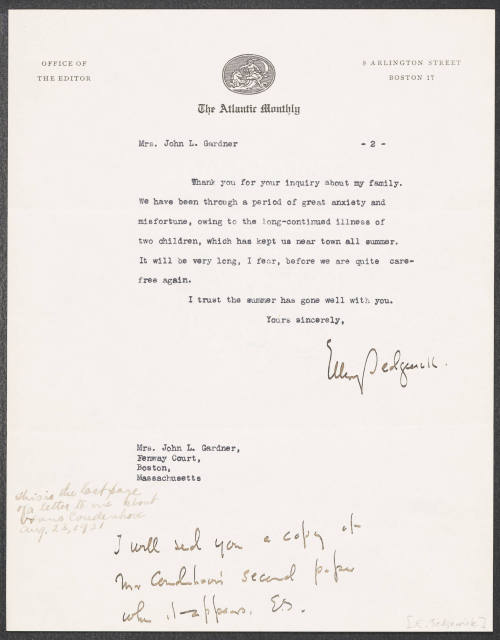

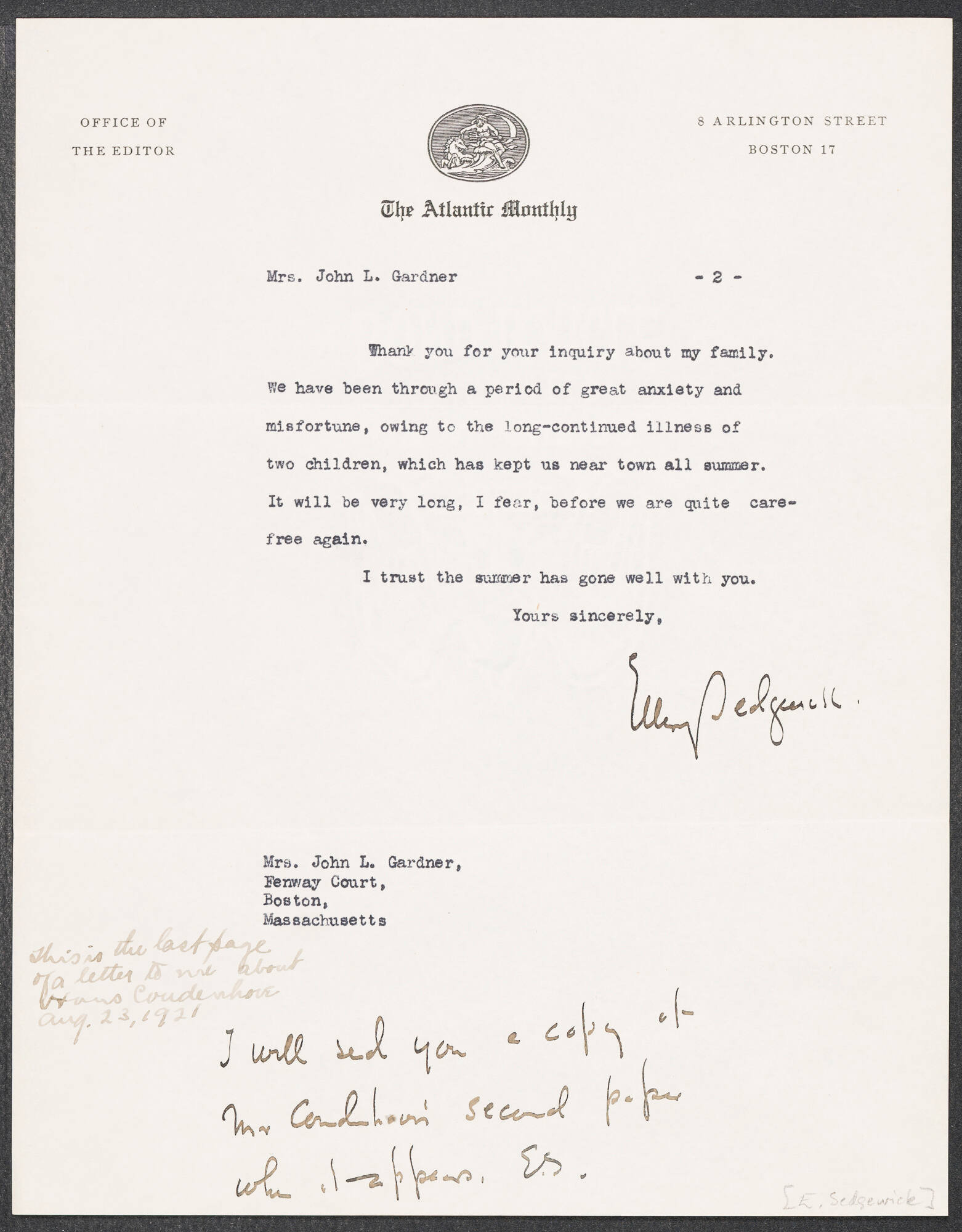

The following year Sedgwick married Mabel Cabot; they had four children. He also worked as editor of Appleton's Booklovers Magazine, and after leaving the American in 1906 he was employed a year at McClure's Magazine, a muckraking leader, and then briefly as a book editor for D. Appleton and Company. After 1909 his chief focus was the Atlantic Monthly; he also edited briefly at Living Age (1919) and House Beautiful (1922).

Sedgwick bought the nationally prominent but down-on-its-luck Atlantic in 1908 for $50,000. With only about 10,000 subscribers and annually running about $5,000 in the red, the Atlantic needed fresh ideas and innovation. It got just this from Sedgwick, who found in the magazine the most absorbing challenge of his career. By 1921 his efforts, which included adding substantial political, economic, and social coverage, had attracted a modern generation of readers surpassing 100,000. In 1922 the New York Times Book Review stated, "There is no use arguing the question--the Atlantic Monthly is not the staid magazine that refreshed our grandfathers. It has grown lively during recent years."

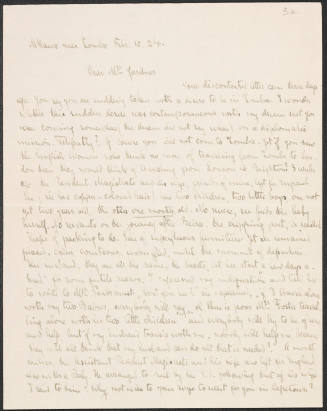

Sedgwick gently masterminded the Atlantic's shift from its emphasis on belles lettres to more hard-hitting coverage of contemporary affairs. According to Frederick Lewis Allen, who worked with Sedgwick, the editor "resolved that the Atlantic should face the whole of life, its riddles, its adventures; the critical questions of the day, the problems of the human heart; and that no subject should be taboo if only it were discussed with urbanity." This editorial courage extended to religious topics, a noteworthy stance during the era of the sensational John Scopes "monkey trial," in which religious fundamentalists attempted to quash the teaching of evolution. Sedgwick's many wellsprings of story ideas for the Atlantic included his daily perusal of newspapers such as the New York Times and the Times of London as well as his extensive correspondence and conversations with intellectuals, writers, and public officials. For advice on important editorial matters he also relied on a close circle of friends including Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter; international financier Thomas S. Lamont; Newton D. Baker, President Woodrow Wilson's secretary of war; and journalist Walter Lippmann.

Occasionally Sedgwick exercised vigorous editorial leadership on the day's most controversial issues. For instance, in 1927 he published articles that directly addressed the issue of the public's prejudice against presidential candidate Alfred E. Smith's Roman Catholicism. Under Sedgwick the Atlantic published other distinctive, influential pieces on contemporary social and political issues. These include Frankfurter's essay on the Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti case (Mar. 1927) and Rear Admiral William S. Sims's sharp critique of the politics of navy promotions (Sept. 1935).

Sedgwick also preserved the Atlantic's tradition of publishing strong literary fiction and poetry, making it the first American commercial magazine to publish an Ernest Hemingway short story ("Fifty Grand," July 1927).

Sedgwick also published writers such as H. G. Wells, Gertrude Stein, Jessamyn West, Eudora Welty, Louis Auchincloss, Randolph Bourne, and Robert Frost (although he once rejected some of Frost's verse with a note that stated, "We are sorry but at the moment the Atlantic has no place for vigorous verse"). Although some of Amy Lowell's poetry appeared in the Atlantic, the 1912-1925 correspondence between Sedgwick and the poet shows that the editor sometimes did not fully fathom the meaning or value of Lowell's work. As Ellery Sedgwick III observed, the editor was an "aesthetic conservative," while Lowell was the opposite.

In 1939 Sedgwick sold the Atlantic for a handsome profit; he maintained that he was not stepping down because of his split with his staff over his controversial support of General Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War. Thereafter he wrote book reviews and reminiscences. The Happy Profession, his 1946 autobiography, is a revealing account of his years at the Atlantic. For example, he wrote that "it has never occurred to me to change the colophon of the Atlantic to a distaff, and I have taken conscious pains that a preponderance of its contributors should be masculine." He added, "My friend [Edward] Bok [editor of Ladies' Home Journal] pointed out that I was sinning against the light of the cashbox, but I took comfort in the monthly comment of the historian, William Roscoe Thayer, who invariably commented: 'I see the men are still ahead in this month's Atlantic.' "

After Mabel Cabot Sedgwick died in 1937, Sedgwick married Isabel Marjorie Russell in 1939. They had no children. He spent his last years on a large estate in Beverly, Massachusetts, and he often lived in Washington, D.C., during the winters. He died in Washington.

Bibliography

Sedgwick's papers are at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. Information on Sedgwick can be found in Frederick Lewis Allen, "Sedgwick and the Atlantic," Outlook and Independent, 26 Dec. 1928, pp. 1406-8, 1417; Edward E. Chielens, ed., American Literary Magazines: The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (1986); Don E. Fehrenbacher, "Lincoln's Lost Love Letters," American Heritage 32 (1981): 70-80; Louis Filler, Crusaders for American Liberalism (1939); Gerald Gross, ed., Editors on Editing (1962); H. L. Mencken, Letters of H. L. Mencken, ed. Guy J. Forgue (1981); Ellery Sedgwick, ed., Atlantic Harvest: Memoirs of the "Atlantic" (1947); Ellery Sedgwick [III], The "Atlantic Monthly," 1857-1909: Yankee Humanism at High Tide and Ebb (1994); Ellery Sedgwick III, " 'Fireworks': Amy Lowell and the Atlantic Monthly," New England Quarterly 51 (Dec. 1978): 489-508; Ellery Sedgwick III, "HLM, Ellery Sedgwick, and the First World War," Menckeniana: A Quarterly Review 68 (Winter 1978): 1-4; and Henry L. Shattuck, "Ellery Sedgwick," Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings 1957-60, pp. 72, 395-96. Obituaries are in the New York Times and the Boston Globe, both 22 Apr. 1960, and the Atlantic, June 1960.

Nancy L. Roberts

Back to the top

Citation:

Nancy L. Roberts. "Sedgwick, Ellery";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01480.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:03:27 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1836 - 1907, Boston

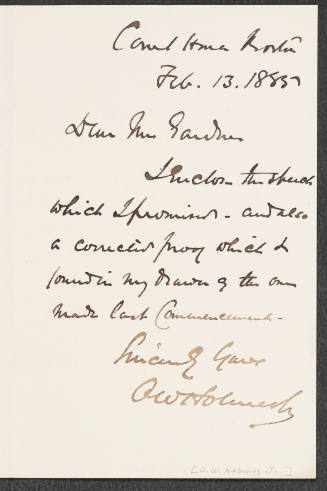

Cambridge, 1827 - 1908, Cambridge

Boston, 1841 - 1935, Washington, D.C.

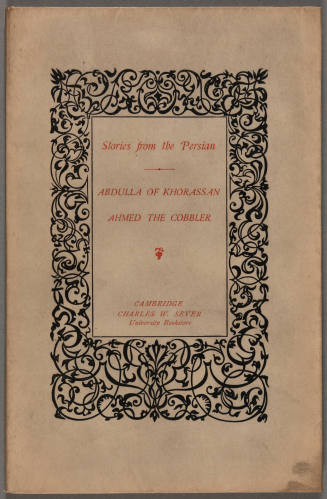

Brighton, Massachusetts, 1839 - 1915, Boston

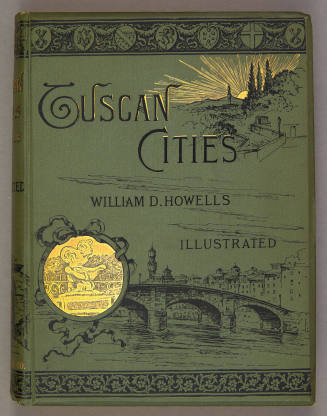

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

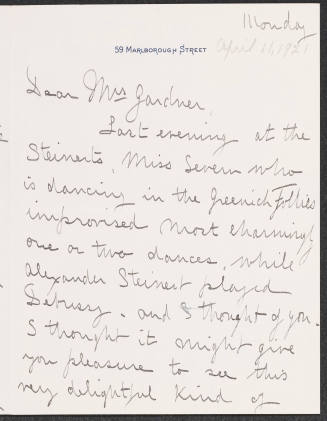

active Lenox, Massachusetts, 1869 - 1962, Boston