Charles Eliot Norton

Cambridge, 1827 - 1908, Cambridge

Date born: 1827

Place Born: Cambridge, MA

Date died: 1908

Place died: Cambridge, MA

First Professor of Fine Arts, Harvard University; influential mentor for a generation of art historians. Norton was born to a wealthy Boston family with strong intellectual interests. His father, Andrews Norton (1786-1853), was a Unitarian theologian and professor of sacred literature at Harvard. He attended Harvard University, graduating with an A. B. in 1846. After college he toured India and Europe, particularly England between 1849-51. With his various attempts at business a failure, he returned to Europe in 1855, remaining there until1857. In Switzerland, Norton met John Ruskin (q.v.), the art critic and historian whose writings deeply affected him. Norton returned to focus on writing and literature. He edited the North American Review between 1864-68 and co-founded The Nation in 1865. His articles at this time demonstrated both a knowledge in art history and archaeology as well as literature. In 1859 he published his Notes of Study and Travel in Italy largely an art-historical travelogue of that country. In 1862 he married Susan Ridley Sedgwick. The Nortons made a trip to Europe in 1868, stopping in England, where his interests in architectural history and enthusiasm for Britain heightened, and then Italy in 1869 before finally settling in Dresden in 1871. In 1872, his wife died in childbirth and a shattered Norton wended his way back to the United States (via England). His cousin, Harvard University President Charles W. Eliot (1834-1926) appointed Norton to be the first lecturer of Fine Arts at Harvard in 1873. On years of even date, he delivered a weekly lecture on Dante; on years of odd date, on the Italian medieval church. A dynamic lecturer though little interested in scholarship, Norton influenced some of the greatest American art historians of the next generation as well as advised the Boston collector Isabella Steward Gardner. He organized an 1874 exhibition devoted to the work of J. M. W. Turner. Classical interests always high with Norton, he founded the Archaeological Institute of America, whose first local society was in Boston, in 1879. A short while later he founded the American Academy in Rome. In 1880, he issued his Historical Studies of Church Building in the Middle Ages. Norton employed a moral interpretation of art history, fuelled by a romantic vision of the middle ages and a disillusion with late-19th century industrialism. His most popular course at Harvard was "The History of the Fine Arts as Connected with Literature." His collected Harvard lectures, published in 1891 as History of Ancient Art, belie the debt to Ruskin's Oxford lectures on beauty as a source for moral uprightness. Norton was the literary executor for Ruskin as well as Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881). As a man of letters, Norton maintained a correspondence with many of the later 19th-century authors, including Charles Dickens, Matthew Arnold, Charles Darwin, Robert Browning and Ralph Waldo Emerson. His cottage in Ashfield in the Massachusetts Berkshires as well as Shady Hill, his home in Cambridge (Massachusetts) were the meeting place for many intellectuals and discussions. In 1898 he retired from Harvard. At Ruskin's death in 1900, Norton became his literary executor. A Charles Eliot Norton Professorship of Poetry (a distinguished visiting professorship in the Faculty of Arts) at Harvard was established in 1925. Norton never supervised a doctoral dissertation, wary of the professionalization of the discipline. Harvard-trained art historians influenced by his teaching included Bernard Berenson (q.v.), Edward Forbes (q.v.), Paul J. Sachs (q.v.), and Rathfon Post (q.v.) among many others. His son, Richard Norton (q.v.), was an archaeologist and art historian as well.

Methodologically, Norton followed a connoisseurship mode of art history, prevalent among the Italo-Anglo and art historians, eschewing German methods of art as a historical phenomenon. Like many English-speaking art scholars, he was deeply affected by the writings of Ruskin (q.v.) whom he knew personally from his trips to England, and whose writing he promoted in America. Norton's lectures and writing focused on Italian art and civilization, paralleling the aesthetics of Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites, which linked esthetic purity to social reform. In Church Building in the Middle Ages he suggested that spiritual values, such as those embodied in the middle ages, led to the creation of fine art while materialism, such as that of his own age, poisoned it. Democracy, he mused may be incompatible with a "healthy culture." His Ruskin-sentimentalist views did not prevent him from championing modern technology, especially the mass reproduction of art. Unashamedly subjective, his influence rests largely on the scholars he encouraged rather than his own writings.

Home Country: United States

Sources: Bazin, Germain. Histoire de l'histoire de l'art; de Vasari à nos jours. Paris: Albin Michel, 1986, p. 540; Calder, William M. "Charles Eliot Norton." Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology. Nancy Thomson de Grummond, ed. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996, vol. 2, p. 812; Vanderbilt, Kermit. Charles Eliot Norton: Apostle of Culture in a Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1959; Turner, James. The Liberal Education of Charles Eliot Norton. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999; Norton, Sara, and Howe, Mark Antony DeWolfe, eds. Letters of Charles Eliot Norton, with Biographical Comment by his Daughter. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913; [obituary] "Dr. C. Eliot Norton Dies in Cambridge." New York Times October 21, 1908, p. 1.

Bibliography: Letters of Charles Eliot Norton. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913; List of the Principal Books Relating to the Life and Works of Michel Angelo. Cambridge, MA: Press of J. Wilson and Son, 1879; and Ruskin, John. The Correspondence of John Ruskin and Charles Eliot Norton. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987; and Ruskin, John. Letters of John Ruskin to Charles Eliot Norton. 2 vols. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1905; [exhibition curated], Ruskin, John. Notes on Drawings. Cambridge: University Press, John Wilson and son, 1879; Historical Studies of Church-building in the Middle Ages: Venice, Siena, Florence. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1880; Notes of Travel and Study in Italy. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company 1859; Brown, Harry Fletcher, and Wiggin, William Harrison, eds. History of Ancient Art. Boston: A. Mudge & Son, 1891. (Dictionary of Art Historians)

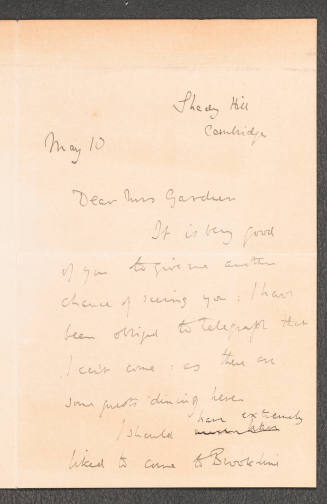

Norton, Charles Eliot (16 Nov. 1827-21 Oct. 1908), scholar and critic, was born at "Shady Hill," his family's estate in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His parents were Andrews Norton, biblical scholar and man of letters, and Catharine Eliot, daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant. Charles grew up in an academic household frequented by George Ticknor (his uncle), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and others of the literary elite of patrician Boston. The intellectual bent developed in this childhood grew more decided at Harvard College, where his closest friend was Francis J. Child, later famed for "Child's Ballads."

Upon graduation in 1846 Norton apprenticed himself in the East India trade. Mercantile duties by no means precluded other interests. He helped a new friend, Francis Parkman, prepare The California and Oregon Trail (1849) for the press. In 1847 appeared the first of Norton's own numerous publications, an article on Coleridge in the North American Review (followed in 1848 by one on William Tyndale and in 1849 by another on the Mound Builders: the miscellany was to be characteristic). In these years he also set up a night school for Irish immigrants, possibly the first such school in the United States.

In 1849 Norton sailed as supercargo to Madras and Calcutta. Fascinated by India, he sought out both British colonial officials and Indian leaders--an early sign of two of Norton's most consequential qualities, omnivorous curiosity and a capacity for friendship with diverse individuals. Commercial duties completed, he traveled across the subcontinent by boat and palanquin to investigate Indian culture and imperial rule. Confrontation with India sharpened Norton's budding sense of cultural evolution as well as his commitment to American republicanism. From Bombay Norton sailed for Europe, visiting Alexandria, Smyrna, and Corfu en route.

His arrival in Venice in March 1850 marked an epoch in his life. The richness of European culture, appreciated before at second hand, overwhelmed him on direct experience. Norton crisscrossed Italy, France, Britain, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria by train, coach, boat, mule, and on foot, settling for weeks at a time in London, Paris, and Florence. He gained entry through his privileged connections to salons, clubs, ateliers, and private collections, dining with Scottish peers, English scientists, French painters, Swiss peasants, American expatriates. The friendships Norton formed initiated the network of British acquaintance that shaped his career, while the linguistic skills he solidified enabled his later scholarship.

He returned home in January 1851. A miscellany of philanthropic and literary activity filled his hours outside the countinghouse: teaching in the night school and, for several months, French at Harvard; writing and lecturing about his Indian experiences; erecting model tenements for the poor; editing two hymn books; and elaborating his conservative reformism in the anonymous Considerations on Some Recent Social Theories (1853). Summers in Newport, Rhode Island, in the 1850s expanded his circle to include many New York artists who summered there. Their acquaintance sharpened Norton's already lively appreciation of painting and drawing. During these years he developed the two friendships that were to matter most: those with George William Curtis (first encountered in Paris in 1850) and James Russell Lowell.

By 1853 Boston's India trade was rapidly declining, but not so rapidly as Norton's interest in it. Andrews Norton's death in that year left Charles in charge of the family's considerable wealth but uncertain of his own future. His literary and artistic bent (extending even to an appreciative review of Leaves of Grass in 1855) was obvious; what career it might lead to was not. Moreover, Norton's health, never sturdy, was growing shakier. The doctors advised Europe. In October Norton sailed, with his mother and two unmarried sisters.

For a sick man, Norton ingested Europe with a healthy appetite. A three-week tramp across Sicily by mule and foot with Lowell and an English friend in the spring of 1856 suggests at least one stretch of considerable vitality. But in general Norton's frenetic pace of 1850 settled down into long stays in a few cities--London, Paris, Florence, Venice, and, for a total of eight months, Rome--varied by shorter visits elsewhere. He looked at paintings and buildings with as much fascination as before but with a cooler, more practiced eye. He began seriously to translate Dante. His acquaintanceship from 1850 expanded into a broader and firmer network of lasting transatlantic friends, most of them artists and writers: the Brownings, Arthur Clough (first befriended in Boston), Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Elizabeth Gaskell, John Simon, William Morris, and, ultimately the closest, Edward and Georgiana Burne-Jones and John Ruskin. When Norton returned to Shady Hill in August 1857, he had not entirely recovered his health, but he had moved closer to a literary career.

Over the next few years, this vocation gained sharper focus. For the new Atlantic Monthly he wrote frequent articles and reviews, including the first American account of the discovery of the Roman catacombs and in 1859 his meticulously literal partial translation of Dante's Vita Nuova (privately printed later that year as a book). In the same year Norton published Notes of Travel and Study in Italy, which became a respected companion for the cultivated English or American tourist.

Meanwhile his personal life was assuming its mature form. Election to the Saturday Club in 1860 signaled his elevation into Boston's literary establishment and deepened into permanent friendships his acquaintance with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809-1894), and Samuel G. Ward. In May 1862 Norton brought home to Shady Hill a wife, Susan Ridley Sedgwick, the orphaned daughter of Theodore Sedgwick (1811-1859) and great-niece of the novelist Catharine M. Sedgwick. They had six children. In 1864 the Nortons took up what was to be a lifelong summer residence in Ashfield, a small town in western Massachusetts. Ashfield symbolized for Norton the honest life, simple manners, broad prosperity, and homogeneous population that he attributed to the early republic--qualities the loss of which, he came to believe, endangered republican democracy in America.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, Norton added occasional Union propaganda to his literary output. Early in 1863 he became editor of the New England Loyal Publication Society, which supplied newspapers with pro-Union boilerplate. In October 1863 Norton also took over, with his friend Lowell, the editorship of the North American Review. Lowell supplied prestige and frequent articles; Norton did the bulk of the editorial work and wrote some sixteen articles and many shorter reviews over the next four years. Two of the articles, "Religious Liberty" (1867) and "The Church and Religion" (1868), expressed Norton's growing heterodoxy. He enlivened the staid North American, publishing the first articles of writers such as Henry Brooks Adams and Henry James, Jr.

Norton used the Review, and the Loyal Publication Society to promote national and liberal principles. To infuse these more widely into American politics, in 1865 he helped Edwin L. Godkin to found the weekly Nation in New York. For the next three years Norton served the Nation as de facto chief editorial consultant and fund raiser, as well as writer of over twenty-five articles and reviews. He still found time to complete his translation of the Vita Nuova (1867). But Norton's health began again to crumble. Sheer pressure of work could explain the decline, but his letters also suggest restlessness with journalism, though no clear idea of another career.

In 1868 he resigned his editorship of the Review, left the Nation to Godkin, and in July sailed with wife, mother, sisters, and children to England. Most of the first year abroad was spent in England with old friends and new. Notable among the latter were Leslie Stephen, Dickens, Mill, Darwin, G. H. Lewes, and George Eliot. Many hours were passed with Ruskin, whose views on art powerfully influenced Norton. In May 1869 the Nortons left England, passing the summer near Vevey, Switzerland, then heading for Italy in October. For the next year and a half they rented palazzi in Florence, Siena, and Venice, finally settling in Dresden in September 1871.

During this nomadic interlude Norton introduced the Rubaiyat to American readers, sent home a first-hand account of the Vatican Council, and assailed England's class-ridden social order. He so despaired of the extremes of wealth and poverty in Europe that he welcomed the Paris Commune as helping to destroy a hopeless social order, to make way for the slow and painful evolution of a better; he cheered Italian unification as a small step in this evolution. News from home of political corruption soured his hope that the Civil War had regenerated the republican ideals of the American Revolution; and for the United States, too, he more and more pitched his hopes in the distant future. But for the most part Norton devoted himself to the study of medieval and Renaissance art and literature, burrowing in Italian archives and spending day after day in galleries. The translator of the Vita Nuova grew into a scholar of literature, the amateur of painting into an expert art historian. In this work Norton seemed to have no particular vocational aim in view, though he did toy with the idea of returning to Harvard--an institution, he thought, that could contribute a little to resisting the American slide from republican ideals into plutocracy. Meanwhile, his drift away from Christianity had in 1869 eventuated in agnosticism. He now found in art and in the slow progress of humanity the spiritual ideals and consolation once provided by religion.

This worldview was put to the test in February 1872, when Susan Norton died after childbirth. Shattered, Charles left Dresden and led his household gradually back to Paris for the summer, thence to London, where he passed a grim winter, spending his time chiefly with Ruskin, Leslie Stephen, and, surprisingly, Thomas Carlyle, forming a close friendship with the old man. The family returned to Shady Hill in May 1873.

Charles W. Eliot, the new president of Harvard and Norton's first cousin, invited him to join the faculty. Mostly to distract himself from the loss of his wife, Norton agreed. He began as an annual lecturer in the fall of 1874 and the next year became the first professor of art history in the United States. In teaching, Norton brought his faith in art to bear on his anxieties about the future of republican democracy. Exposure to great art and literature, Norton believed, built character and infused high ideals: an antidote for the creeping materialism and self-seeking that infected the leadership classes of the United States. His lectures mixed intellectual history and connoisseurship with denunciations of contemporary degeneracy. A slight man with a voice that students often had to strain to hear, Norton nonetheless attracted them in droves, liberally dispensing easy grades in order to do so.

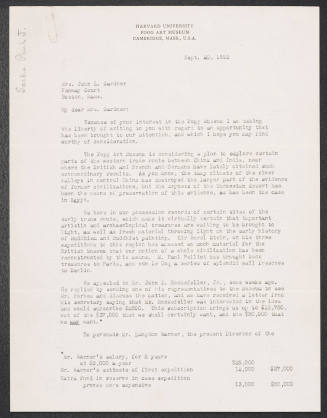

He also carried his message outside Harvard College, reviewing scores of books on art and literature for the Nation and offering public lectures on subjects ranging from medieval architecture to Dante. He organized exhibitions (notably one in 1874 devoted to J. M. W. Turner, for whose work Norton was the great American advocate) and promoted mass reproduction of art. He popularized poetry through editions of individual poets and a widely reprinted newspaper column. He edited the Heart of Oak books (1894-1895), a series of anthologies for young readers. He advised American collectors of European art, most famously Isabella Stewart Gardner (the Gardner Museum in Boston ultimately resulting). Because of his close ties with Britain, he was perhaps the single most significant personal link between American and British intellectual life, introducing books and people from one side of the Atlantic to the other.

By the late 1880s Norton had become the most prominent cultural critic in the United States, though ill health from time to time stemmed his prodigious output. He urged improvement of aesthetic taste, education, and intellectual life, performing for Americans something like the function of Matthew Arnold in England. As in his teaching, Norton insisted that the fate of the republic depended on its moral tone; and he joined with his friend and Ashfield neighbor George W. Curtis in the campaign for civil service reform.

Though Norton's scholarship was rarely of enduring quality, he nevertheless had far-reaching influence on academic knowledge. His Historical Studies of Church-Building in the Middle Ages: Venice, Siena, Florence (1880) helped to found medieval studies in the United States. In 1879 Norton founded the Archaeological Institute of America, which became the major professional society for archaeologists in the United States; and through it for the next decade he was the chief organizer of American archaeology, establishing in 1882 the American School of Classical Studies at Athens and (overcoming his own classicist bias) underwriting the early work of Adolph Bandelier in the American Southwest. In the late 1870s Norton took over from Lowell the teaching of Dante at Harvard and in 1880 organized the Dante Society of America. Through his teaching, the Dante Society, and his critical writings, he established academic Dante studies in this country. His own prose translation of the Divina Commedia (1891-1892) was long standard. In later years he turned his attention to English and American poets. "The Text of Donne's Poems," published in 1896 in [Harvard] Studies and Notes in Philology and Literature, was seminal in modern Donne scholarship. Ambivalent about the professionalization of scholarship, Norton never directed a doctoral dissertation. But among students who felt his hand powerfully were the art historian Bernard Berenson, the critics George E. Woodberry and Irving Babbitt, the Dante scholar Charles H. Grandgent, and Arthur R. Marsh, the first professor of comparative literature in the United States.

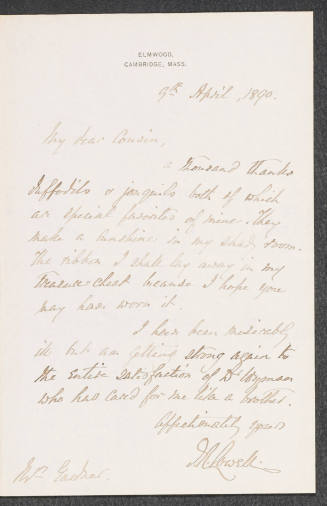

As his older friends died, their families often asked Norton to edit their literary remains. These editions, despite adherence to the conventions of Victorian editing, were standard resources for a long time; a few still are. Norton edited the Philosophical Discussions of Chauncey Wright in 1878 and the Emerson-Carlyle correspondence in 1883. After James A. Froude's intimate revelations of Carlyle, the latter's angry relatives turned to Norton; there resulted three volumes of Carlyle's letters (1886, 1887, 1888) and an edition of his Reminiscences (1887). Norton later published Two Notebooks of Carlyle (1898). He also edited letters (1893), lectures (1891), and poems (1895) of Lowell; the poems (1893) and Dante translations (1893) of Thomas W. Parsons; Orations and Addresses of Curtis (1894); Emerson's letters to Samuel G. Ward (1899); and Ruskin's letters to Norton himself (1904).

Norton retired from Harvard in 1898, characteristically provoking a national storm by using his last lecture to denounce the Spanish-American War as the knell for American republican ideals. For the next few years he sustained an active schedule of publication, including a revision of his Divine Comedy (1902). He died at Shady Hill.

Bibliography

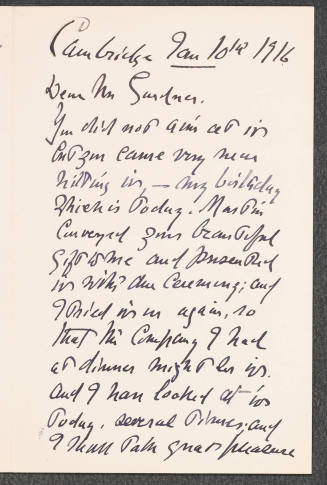

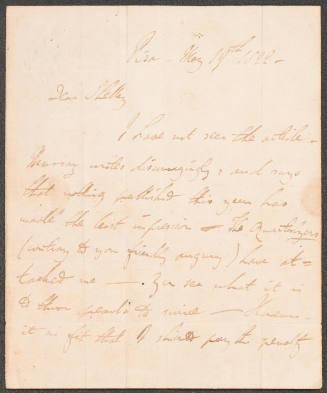

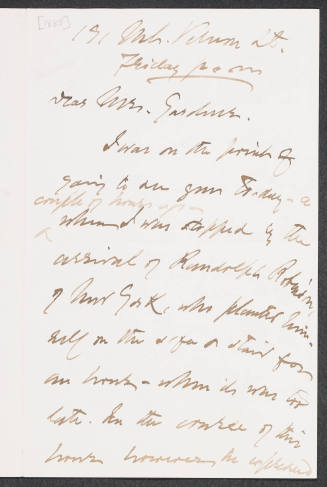

The Charles Eliot Norton Papers are in the Houghton Library, Harvard University. There is much correspondence in other collections at the Houghton, in the Harvard University Archives, and in some hundred other repositories in the United States and Europe. Published correspondence appears in Sara Norton and M. A. DeWolfe Howe, Letters of Charles Eliot Norton with Biographical Comment (2 vols., 1913), and John Lewis Bradley and Ian Ousby, eds., The Correspondence of John Ruskin and Charles Eliot Norton (1987). The standard biography is by James Turner, The Liberal Education of Charles Eliot Norton (1999). See also Kermit Vanderbilt, Charles Eliot Norton: Apostle of Culture in a Democracy (1959), and--for a briefer assessment--Martin Green, The Problem of Boston: Some Readings in Cultural History (1966).

James Turner

Back to the top

Citation:

James Turner. "Norton, Charles Eliot";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-01212.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 12:28:38 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated10/26/24

Cincinnati, Ohio, 1853 - 1935, London

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1819 - 1891, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

New York, 1878 - 1965, Cambridge, Massachusetts