Denman Waldo Ross

Cincinnati, Ohio, 1853 - 1935, London

LC Heading: Ross, Denman Waldo, 1853-1935

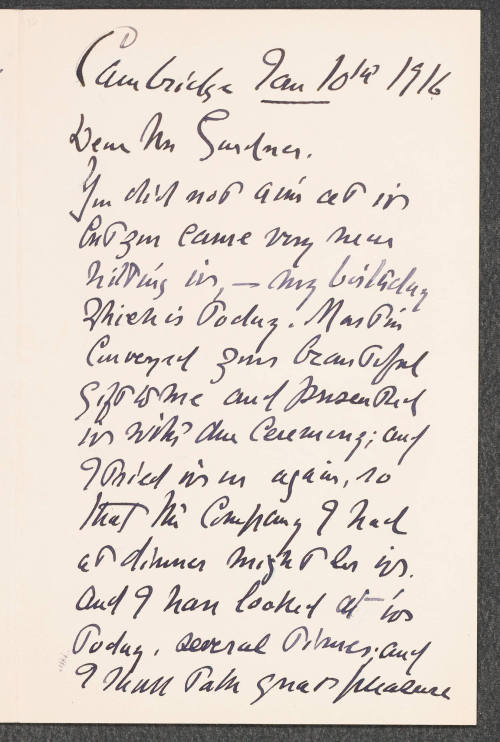

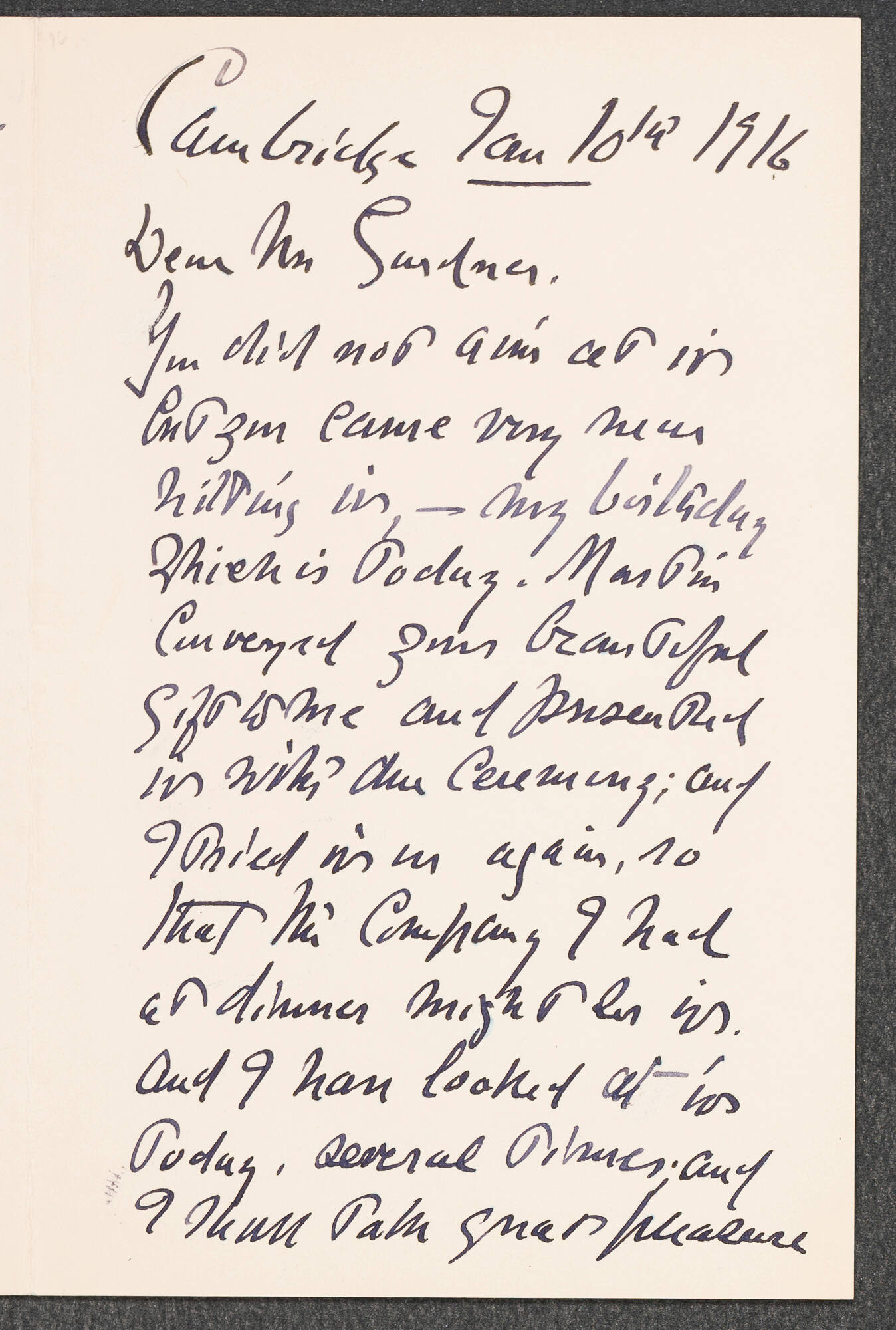

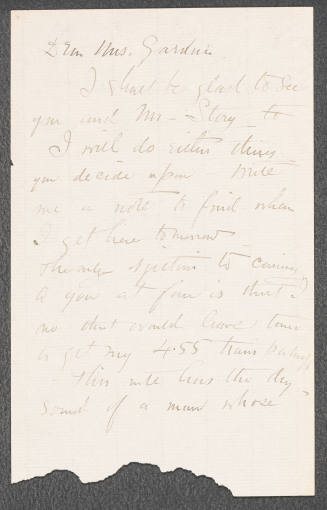

Ross, Denman Waldo (10 Jan. 1853-12 Sept. 1935), art collector and design theorist, was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, the son of John Ludlow Ross, a merchant, and Frances Walker Waldo. Through his mother's family Ross maintained strong ties with the Boston area, and the family moved to Cambridge permanently upon Ross's entry to Harvard in 1871. Graduating with highest honors in history in 1875, he returned for further study and in 1880 earned one of the earliest doctorates awarded by the Harvard history department. Under the tutelage of Henry Adams and others, Ross was trained in "scientific history," a methodology that emphasized objectivity and universal principles; he would carry this training over into his later work in design. Ross wrote a number of articles in the early 1880s, and his dissertation was published in 1883 as The Early History of Land-Holding among the Germans. In 1885 he was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

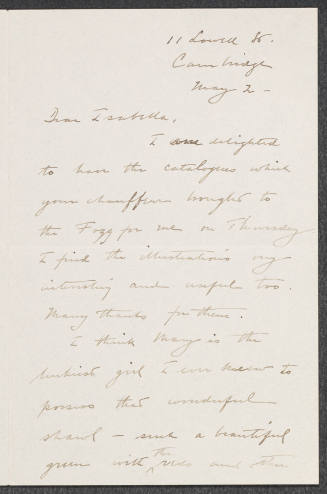

While at Harvard Ross also attended Charles Eliot Norton's lectures and became an admirer of John Ruskin's work. In the mid-1880s Ross's attention turned from history and more directly to the arts. Real estate investments provided an independent income that allowed him to travel extensively and collect art objects throughout his life. He studied informally in Italy with the painter H. R. Newman and in 1887 attended the Académie Julian in Paris. Back in Boston he became an active member of both the Boston Society of Architects and the Boston Architectural Club. He also began to lend and donate to various museums many of the objects he collected on his travels, believing that original works of art had to be viewed in order to increase appreciation of them: of the 16,000 objects he collected over his lifetime, he gave 11,000 to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (for which he became a trustee in 1895), 1,500 to the Fogg Art Museum (including the Ross Study Series--a collection of materials intended for pedagogical use that included drawings, photographs, quotations, and works of art), and a collection of textiles to Teachers College, Columbia University. He collected textiles, ironwork, ceramics, and sculpture as well as paintings; and he established significant collections of non-European art, particularly Asian, Indian, and South American. He had little interest in the historical, cultural, or chronological significance of an object, focusing instead upon its formal characteristics.

Ross's activities as a collector coincided with his interest in design theory. He became critical of much contemporary work and sought to improve it:

In the years between 1890-1900 I became interested in the idea of Design. I had been travelling in Europe and studying pictures, the pictures which were produced during the Renaissance by the great masters, the masters who were very much disregarded and forgotten by the impressionist painters. Slowly I began to lose my interest in impressionist work. It seemed to me so superficial when compared with the work of the old masters. I felt that in [the] unprecedented activity of the impressionists the craft of painting had been forgotten and with it the love of order and intelligent appreciation of beauty. (Ross papers)

To restore "order" to painting, Ross developed his "Theory of Pure Design" in which he applied to art the scientific methodology he had used as a historian. He abstracted the universal principles of harmony, balance, and rhythm and focused attention upon the elements of design: the dot, line, outline, and color. He first articulated his theory in the article "Design as a Science" (Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences [1901]) and elaborated upon it in A Theory of Pure Design (1907). His work in color theory (addressed most fully in The Painter's Palette [1919]) was particularly respected by contemporaries. Although his work relied on abstraction, Ross also retained the Ruskinian notion that art should express an idea. Ross had no interest in abstract form as an end in itself and insisted that Pure Design remain a preliminary exercise to the goal of representational art. In On Drawing and Painting (1912) he specifically criticized the work of the postimpressionists and futurists. By grounding design in scientific methods, in investigations in the physio-psychological perception of form, and in geometry, Ross hoped to provide an objective basis for teaching design independent of stylistic preference. Further, he believed that exercises in order would improve the moral and civic life of students.

Ross began to teach in the department of architecture at Harvard in 1899; in 1909 his classes were moved to the department of fine arts, where they remained until his death. In conjunction, from 1899 to 1914 (with the exception of 1907) he also taught a summer course that was open to professionals--art educators, artists and artisans, curators, and architects--from across the continent. "The influence which he exerted indirectly as well as directly through his teaching is incalculable" (Obituary by E. Forbes, Bulletin of the Fogg Art Museum, Nov. 1935). Ross continued to travel, teach, and collect through the 1920s, refining his theories by keeping abreast of Hardesty Maratta and Jay Hambidge's work in dynamic symmetry. A bachelor, he died while traveling in London.

Ross's collecting and design theories contributed to the development of formalist aesthetics in the United States. He maintained a warm friendship with Bernard Berenson throughout his life; Roger Fry, deeply impressed with Ross's work, cited him in his 1909 "Essay on Aesthetics." Yet Ross's development of a pedagogical method of design--which led to friendships with art educators Arthur Dow and Henry Bailey--suggests a wider sphere of significance and influence. His emphasis on objectivity and universal principles colored not only art education in the classroom but also architecture, museum development, and art historical scholarship in the early twentieth century. His Theory of Pure Design in many ways grounded the more philosophical work of his Harvard colleagues George Santayana and Hugo Münsterberg. Despite Ross's reliance on science for objectivity and his emphasis on process in design, his commitment to transcendent ideas led John Dewey's colleague Albert C. Barnes to criticize his methods in 1925. But as Charles Hopkinson later suggested in an obituary, "his teaching was extremely valuable, for it came at a time when there was little or no idea (in this part of the world, at least) of discovering what might be described as 'terms of Art' and of formulating these terms in an orderly way so that an artist might have an instrument and a language in which to describe nature and his ideas of beauty" (Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences [1937]). In many ways Ross's work provided a bridge between Ruskinian moralism and Dewey's pragmatism in American aesthetic thought.

Bibliography

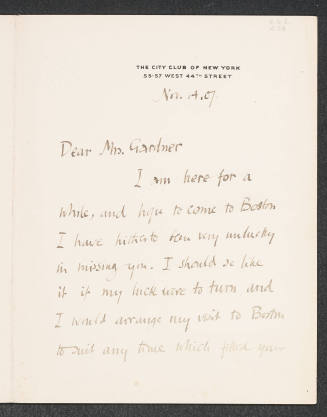

The bulk of Ross's papers is located in the Harvard University Art Museum Archives; a large collection of his drawings and sketches is held by the Prints and Drawings Department of the Fogg Art Museum; a collection of letters is in the Houghton Library, Harvard University. Articles by Ross include "The Arts and Crafts: A Diagnosis," Handicraft 1 (Jan. 1903): 229-43. Theodore Sizer (a student of Ross's) wrote the entry in the Dictionary of American Biography, which provides a detailed bibliography. For Ross's role in formalist aesthetics, see Mary Ann Stankiewicz, "Form, Truth, and Emotion: Transatlantic Influences on Formalist Aesthetics," Journal of Art & Design Education 7, no. 1 (1988): 81-95, and Marianne Martin, "Some American Contributions to Early Twentieth-Century Abstraction," Arts Magazine, June 1980, pp. 158-65. For Ross's contributions to the MFA see Walter M. Whitehill, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: A Centennial History (2 vols., 1970), and Carol Troyen and Pamela S. Tabbaa, The Great Boston Collectors: Paintings from the Museum of Fine Arts (1984). For an explication of the Theory of Pure Design, see Marie A. Frank, "The Theory of Pure Design and American Architectural Education in the Early Twentieth Century" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Virginia, 1996).

Marie Frank

Back to the top

Citation:

Marie Frank. "Ross, Denman Waldo";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00756.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 10:52:19 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated2/19/25

Cleveland, 1880 - 1974, Westport, Massachusetts

Boston, 1849 - 1921, Dublin, New Hampshire

Worcester, Massachusetts, 1889 - 1945, New York, New York

Beverly, Massachusetts, 1851 - 1930, Beverly, Massachusetts

Victoria, Australia, 1882 - 1961, New York