Benchley Robert Charles

Worcester, Massachusetts, 1889 - 1945, New York, New York

After receiving his diploma in 1913 (officially as a member of the class of 1912), Benchley edited a Curtis Publishing house organ and worked as a "welfare secretary" for a paper mill company. In June 1914 he married Gertrude Darling, whom he had announced he would marry when he was in the third grade. They soon moved to New York City, then to suburban Scarsdale. They had two sons. Benchley's first published humor appeared in 1914 in Vanity Fair. He worked in social service for the East Side House and the Urban League but by 1916 was a reporter for the New York Tribune. He then served as associate editor of the Tribune Sunday magazine (and was fired in May 1917 when the magazine was discontinued).

Over the next two years Benchley held a succession of jobs in New York City and Washington, D.C., as a critic and publicity agent for: Vanity Fair, Broadway producer William A. Brady, the U.S. Aircraft Board, the New York Tribune Graphic (a new Sunday rotogravure section), and the Liberty Loan. In 1919 he was appointed managing editor of Vanity Fair but resigned in protest in 1920 (along with Robert E. Sherwood) when Dorothy Parker was fired by the magazine for criticisms of Billie Burke (Mrs. Florenz Ziegfeld) and other show people. Resolving to live by freelance writing, he and Parker then memorably shared a tiny office and supposedly the cable address "Parkbench." The cable address was apocryphal--but indicative of the place that both would occupy in legends of New York in the 1920s.

Benchley then began a New York World column, "Books and Other Things," which ran through 1921, and served as drama critic for the humor magazine Life from 1920 to 1929. His first collection of humor, Of All Things, appeared in 1921. Benchley was among the Algonquin Round Table wits from 1919 into the 1930s. "The Vicious Circle" included Parker, Sherwood, Harold Ross, Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Marc Connelly, Harpo Marx, Edna Ferber, and Russel Crouse. Many were New Yorker contributors after 1925.

Benchley wrote for Ross's New Yorker beginning in December 1925 and contributed "The Wayward Press" column under the pseudonym "Guy Fawkes." He served as the new magazine's drama critic from 1929 to 1940 and helped establish its tone of humorous urbanity. The bemused yet serious protest at the ironies of modern life that was at the center of Benchley's appeal is well illustrated in the following New Yorker comment: "I would like to protest the killing by a taxicab . . . of Wesley Hill, the angel Gabriel of "The Green Pastures" [Connelly's Pulitzer Prize-winning play based on black religion]. There was really no sense in that, Lord, and you know it as well as I do" (20 Dec. 1930).

Benchley's association with Hollywood filmmaking grew out of humorous monologues that continued the tradition of his college humor. "The Treasurer's Report" of 1922 (which he eventually delivered on Broadway as a part of the third Music Box Revue) was filmed in 1928 and appeared as a book in 1930. Also among his forty-eight film shorts were The Sex Life of the Polyp (1928) and How to Sleep, which received an Academy Award as best short film of 1935. In these and in much of his writing his persona was that of the decent, middle-class American--whom he characterized as the "poor boob"--born into comfort yet facing a trying modern world.

By 1938 Benchley's evolving media career had him commuting from coast to coast. He also worked as a radio emcee beginning in 1938 with the highly popular Old Gold program and cut back on his writing for the New Yorker. He considered himself retired from writing by 1943. His last film was made for the U.S. Navy in 1945. He died in New York City of a cerebral hemorrhage and was buried in Nantucket, where he had spent many happy summers.

Bibliography

Robert Benchley's papers are in the Mugar Memorial Library at Boston University. Additional material is housed in the Billy Rose Theatre Collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center. Biographies of Benchley are his son Nathaniel Benchley's Robert Benchley (1955), which includes a useful foreword by Robert Sherwood, and Babette Rosmond's Robert Benchley, His Life and Good Times (1970). Norris W. Yates, Robert Benchley (1968), examines his career as writer and humorist. Both the New Yorker obituary (1 Dec. 1945) and James Thurber's New York Times Book Review article (18 Sept. 1949) help to explain the continuing appeal of Benchley's life and writing. The Benchley Roundup, a Selection by Nathaniel Benchley of His Favorites, comp. Nathaniel Benchley (1954), and The Best of Robert Benchley (1983) are accessible compilations from earlier collections of his work. The "Reel" Benchley: Robert Benchley at His Hilarious Best in Pictures (1950) is a collection of six scripts of his film shorts. Chips off the Old Benchley, comp. Gertrude Benchley (1949), and Benchley Lost and Found: 39 Prodigal Pieces (1970) include previously uncollected material.

Frederic Svoboda

Citation:

Frederic Svoboda. "Benchley, Robert";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00105.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:29:25 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Calais, Maine, 1860 - 1952, Waverly, Masachusetts

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1819 - 1891, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Paris, 1874 - 1965, Nice, France

Albany, New York, 1811 - 1882, Boston

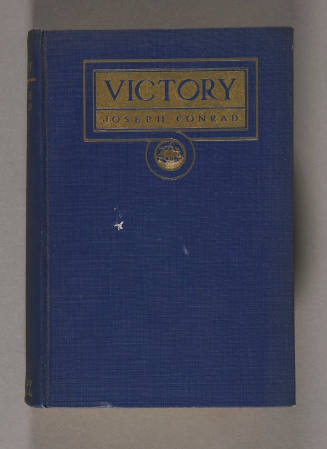

Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1857 - 1924, Bishopsbourne, England

Florence, 1849 - 1912, Asolo