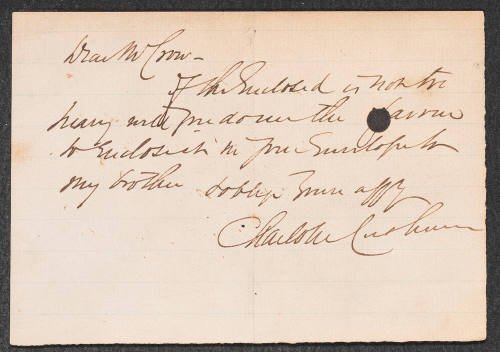

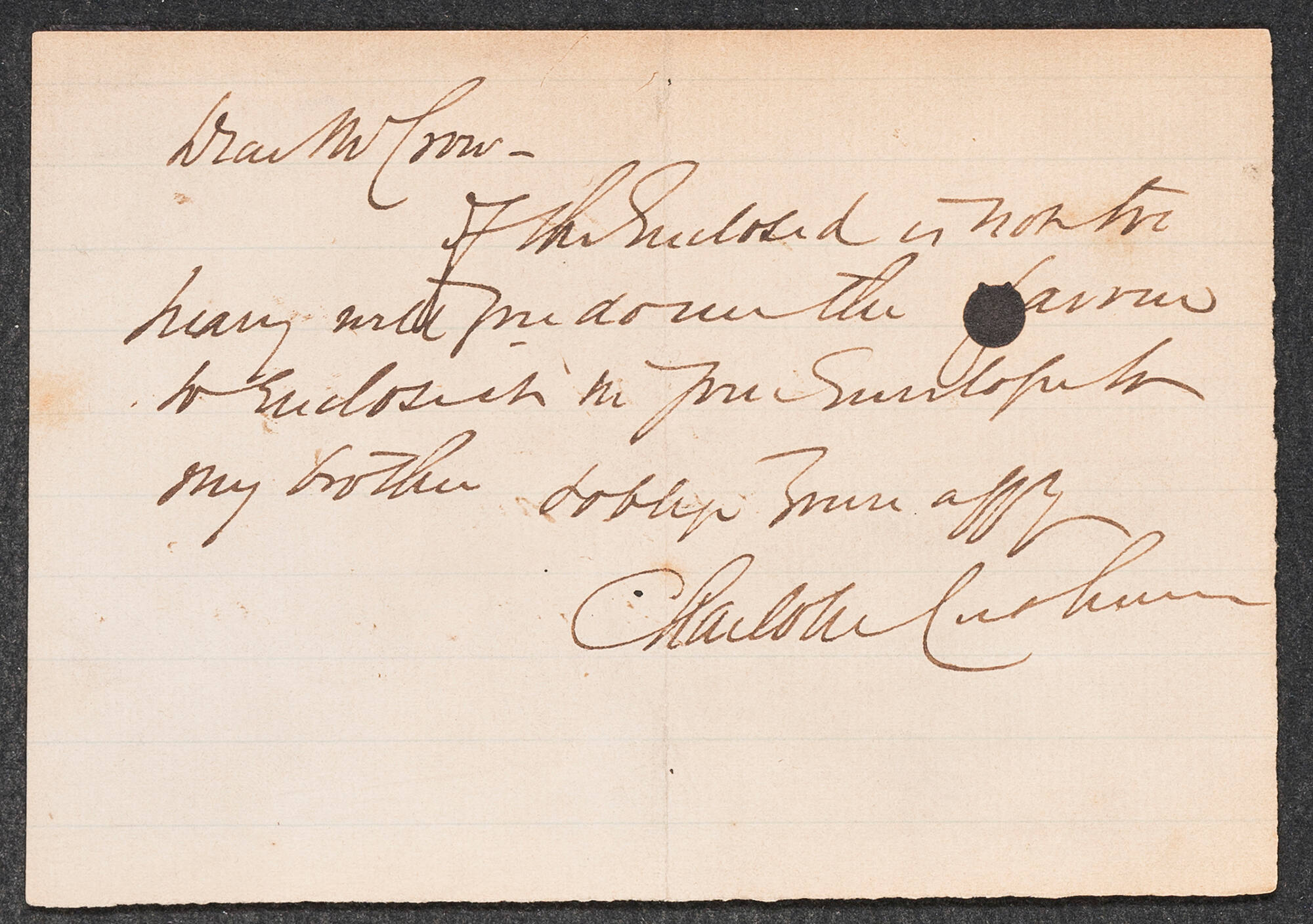

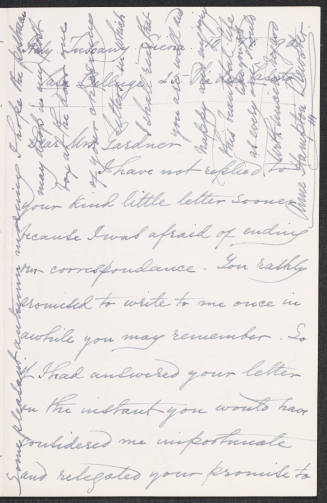

Charlotte Cushman

Boston, 1816 - 1876, Boston

Her education continued in 1829 when she joined the Second Church (Unitarian), where Ralph Waldo Emerson preached his gospel of self-reliance: "The good man reveres himself, reveres his conscience, and would rather suffer any calamity than lower himself in his own esteem." As a member of the church choir, she also learned that with proper training her contralto voice might be her best hope for financial independence.

By 1835, the singing lessons that she had paid for herself resulted in her Boston operatic debut as the Countess Almaviva in Mozart's Marriage of Figaro. The next day the Boston Atlas declared that Cushman had held the stage with "grace and dignity."

Through her singing teacher, she obtained an apprentice position at the St. Charles Theatre in New Orleans. On 1 December 1835, however, her nervous debut there as the Countess Almaviva ended in a fiasco. The next morning, the Bee's newspaper critic declared that, given her incredibly shrill top tones, he would as soon "hear a peacock attempting the carols of a nightingale" as listen to Cushman's "squalling caricature of singing."

Throughout the spring of 1836, as Cushman attempted other operatic roles, the Bee critic did give her one hope. If she confined herself to straight acting parts, she might perform "with success." With that thought in mind, she sought the advice of a fellow performer. "You're a born actress," James Barton told her, "go on the stage." Under his guidance, her acting debut on 23 April 1836 as Lady Macbeth--clutching a pair of daggers, her eyes blazing with obsessed ambition, her chin set firmly to her bloody task--set off a frenzy of cheers.

Two weeks later, when the New Orleans theater season ended, she sailed north to brave the stricter judgments of New York. Borrowing money to buy her costumes, she opened at the Bowery Theatre as Lady Macbeth, transfixing her audience "with the horror of her infernal purpose." Her triumph, however, was short-lived. Nine days later flames roared through the Bowery Theatre, destroying all her costumes. Her contract was cancelled.

Unbowed, Cushman found a better chance to prove her abilities when she played Romeo at New York's National Theatre in 1837. "With a little more fire in the impassioned scenes," the New York Courier would have found her "faultless."

Within weeks she appeared in a role well suited to her broad range of talents. As Meg Merrilies in Sir Walter Scott's Guy Mannering, costumed in rags and clutching a staff in her bony fingers, she was a bent, hollow-eyed crone. Madly screeching or crooning a weird lullaby, she electrified the audience. At the curtain, the actor who had played opposite her rushed to her. "When I turned and saw you," he cried, "a cold chill ran all over me."

As a "walking lady" she was back in New York at the Park Theatre in the fall of 1837, playing chambermaids, old women, tragic queens, comic ladies, and young men. With her "histrionic advantages," the New Yorker critic predicted, Cushman could well become "a general favorite." He sincerely doubted, however, that any audience would praise her appearance. Plain-faced in the extreme--her jaw too prominent, her mouth too wide, her nose too flat--Cushman's future success, in his opinion, must depend on the rich voice and the keen intelligence that shone within her tall, boyish appearance.

At the Park she proved her worth so effectively that she was soon playing Cordelia to the King Lear of America's reigning male star, Edwin Forrest. From there she progressed to star parts in her own right: Lady Macbeth, Nancy Sykes in Oliver Twist, and Romeo.

After three years at the Park, as her confidence strengthened, she asked a veteran English actor what chance she might have in London, the pinnacle of the theater arts. William Chapman's reply was direct: with her "extraordinary gifts," she must go to London and let her talents be known.

Toward realizing that dream, she signed on as "leading lady" at the National Theatre in Philadelphia in August 1842. That position brought her acclaim--her name carried high on the daily playbills--and much more than the $20 per week she had received at the Park. It also brought her an even more taxing routine: in an average week, she played five or six different roles. On 1 September, she was Ellen Rivers in The Patriarch; on the second she was Gabrielle in Tom Noddy's Secret; three nights later she was Nancy in Oliver Twist; on the seventh she was Beatrice in Much Ado about Nothing; and on the eighth she played Smike in Nicholas Nickleby.

Though that year-long routine often left her exhausted, it gave her a chance to play opposite stars whose famous names shed luster upon her own. William Macready, London's reigning tragedian, wrote in his journal, "The Miss Cushman who acted Lady Macbeth interested me much. She has to learn her art, but she showed mind and sympathy with me" (23 Oct. 1843). By the next morning, Cushman was again voicing her great, secret dream. "I mean to go to England as soon as I can. Macready says I ought to act on an English stage and I will."

That day came on 26 October 1844 when she set sail from New York. Safely arrived in London, she mailed letters of application to the major theater managers and then accepted the most attractive offer--from J. M. Maddox at the Princess Theatre. For her London debut on 14 February 1845, she chose Fazio, by Henry Milman. Throughout the early scenes in the play, the other actors seemed wholly indifferent to her as Bianca; the small audience sat cold and silent. The story unfolded to reveal Fazio's illicit affair with Aldabella and his embezzlement of another man's money. When Bianca cried out in anger, "Fazio, thou hast seen Aldabella!" Cushman sensed a sudden excitement out front. Fazio was forced to stand trial for all his misdeeds. Bianca pled passionately for his life, and hearing the sentence of death, she threw herself at his feet and implored his forgiveness. A storm of applause burst from the audience.

Next morning a knock on her door brought all the London papers and a grateful note from Maddox: her success had been "splendid." To the Herald, she had proved herself "a great artist." To the Sun, she was "the greatest of actresses." Not since the debut of Edmund Kean in 1814, it continued, had there been such a debut on "the boards of an English theatre."

After her run at the Princess, Cushman's tour through the provinces brought further acclaim. Only in Edinburgh did she encounter surprise. Her Romeo, while "splendidly acted," left many in her audience strangely disturbed: how could an honorable actress display herself so questionably, playing a man?

In spite of such doubts, by August 1849 Cushman's English career had brought her financial and artistic acclaim and a devoted circle of society friends, among them Jane and Thomas Carlyle. On that note, she sailed for the United States, savoring the chance to enjoy the fruits of her English victory. At home in Boston, when she entered a theater box to watch James H. Hackett as Falstaff, she had hardly taken her seat when a buzz began filtering through the audience. Faces turned up and peered at her, and happy shouts broke out when the theatergoers recognized her: "Three cheers for Charlotte Cushman! Hurray for our Charlotte!"

That initial appearance in 1849 touched off a regal progress through Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. As "one of America's intellectual jewels" (Spirit of the Times), she had come home to great crowds of admirers, who flocked now to see her as Queen Katherine in Shakespeare's Henry VIII, a role in which London critics had compared her favorably to the great Sarah Siddons. That homecoming also brought her a host of new friends: Henry W. Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Julia Ward Howe, and Fanny Kemble.

By 1852, rich and content from her labors, Cushman returned to London, the better to enjoy her wealth in a social routine that included friendships with many of London's intellectual and artistic elite. From there she moved to Rome and opened a lavish house on the Via Gregoriana that she made a social center for expatriate English and Americans, including Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, William Wetmore Story and his wife, and Cushman's American protégées, the young sculptors Harriet Hosmer and Emma Stebbins.

By 1854, however, she was restless for work. Back in London, the Illustrated London News spoke for the crowds that flocked to her nightly performances. "We welcome most heartily this reappearance of Miss Cushman, with powers evidently not diminished, but, as it strikes us, increased."

Lengthy "retirements" followed by eager returns to the stage--performing with top stars like Forrest, Macready, and Edwin Booth--in the United States and England spelled the remaining routine of her acting career. Although eager for rest in Rome and later in her "Villa Cushman" in Newport, Rhode Island, she soon yearned for the stage. After each "irrevocable retirement," her passion for her work would bring her back again.

But by 1874, Cushman had played out her energies. When she opened a brief run at Edwin Booth's Theatre in New York, the papers were happy to note no decline in "her awe-inspiring presence." Her final farewell in New York took place at Booth's on the night of 7 November 1874, when, after her sleepwalking scene in Macbeth, the curtain slowly descended, and the cheering audience leaped to their feet.

Joining her at the footlights, William Cullen Bryant read her a long testimonial. "You have taken a queenly rank in your profession. You have interpreted through the eye and ear to the sympathies of vast assemblages of men and women the words of the greatest dramatic writers." With that, Bryant settled a laurel wreath on her head, a symbol, he said, "of the regal state in your profession to which you have risen and so illustriously hold."

Fighting back tears, Cushman opened her arms and bowed low. Facing the audience, she delivered her life's manifesto. "I found life sadly real and intensely earnest, and in ignorance of other ways to study, I resolved to take therefrom my text and my watchword. To be thoroughly in earnest, intensely in earnest in all my thoughts and in all my actions, whether in my profession or out of it, became my one single idea. And I honestly believe therein lies the secret of my success in life."

In private, Cushman had long entertained a personal conviction no less intense. Traditional society might think as it pleased, but for the abiding ties of the heart she had always, from her earliest friendship with Rosalie Sully, the daughter of Philadelphia painter Thomas Sully, enjoyed romantic attachments with kindred spirits of her own sex. Edinburgh could chide her for playing Romeo and Hamlet, but she would calmly reply that in such "breeches parts" she felt completely at ease. As her career steadily progressed, she enjoyed similar friendships with the English actress Matilda Hays and the American sculptor Emma Stebbins. When breast cancer and pneumonia at last overcame her, she was in Boston in the supportive care of Stebbins, her special companion for twenty years.

After her burial in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, the nation's major newspapers summed up her life. According to the New York Tribune, "The greatness of Charlotte Cushman was that of an exceptional because grand and striking personality." To the New York Times, her fame would be "as enduring as any conqueror's." According to Scribner's magazine, Cushman's art had surpassed that of her most eminent contemporaries, George Eliot, George Sand, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. "They do not stand as high in their respective professions as she stands on the stage."

Through her art and her shrewd investments, she left an estate worth nearly a million dollars. On 21 May 1925, a bust of Charlotte Cushman was unveiled at New York's Hall of Fame for Great Americans. She was the first native-born actress to triumph both in the United States and in Great Britain, and she was at that time the only actress accorded such acclaim.

Bibliography

Major collections of Charlotte Cushman primary sources (letters, playbills, playscripts, scrapbooks of clippings, costumes, photographs, etc.) can be found at the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress, the Harvard University Theatre Collection, the Yale University Theatre Collection, and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. Less extensive collections are available at the New York Public Library, the Boston Public Library, Radcliffe College Library in Cambridge, the Players Club in New York, and the library of the University of Texas in Austin. The major published treatments of Cushman are Emma Stebbins, Charlotte Cushman: Her Letters and Memories of Her Life (1878); Clara Erskine Clement, Charlotte Cushman (1882); W. T. Price, A Life of Charlotte Cushman (1894); Cornelia Carr, Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories (1912); Joseph Leach, Bright Particular Star: The Life and Times of Charlotte Cushman (1970); and Dolly Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer: American Sculptor 1830-1908 (1991). Obituaries are in the New York Times, the New York Herald, and the Boston Advertiser.

Joseph Leach

Back to the top

Citation:

Joseph Leach. "Cushman, Charlotte Saunders";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00266.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:14:37 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Watertown, Massachusetts, 1830 - 1908, Watertown, Massachusetts

Philadelphia, 1819 - 1892, Siena, Italy

near London, 1836 - 1911, Concord, Massachusetts

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1835 - 1894, Appledore Island, Isle of Shoals, Maine

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Krakow, Poland, 1840 - 1909, Newport, California

Bethel, Missouri, 1854 - 1926, Rumford Falls, Maine