Anne M. H. Brewster

Philadelphia, 1819 - 1892, Siena, Italy

Anne Hampton Brewster was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on October 29, 1818 to Maria Hampton and Francis Enoch Brewster. She had one older brother, Benjamin Harris Brewster, who became an accomplished civil lawyer and served as Attorney General of the United States during Chester A. Arthur’s presidency. Anne’s father abandoned the family in 1834, to live with his mistress and their two sons. He provided minimal support to Anne and her mother, forcing them to rely heavily on Benjamin. As a result, Anne found herself managing her brother’s household. Anne maintained an ambivalent relationship with her brother throughout her life.

In fact, according to author Denise M. Larrabee, Brewster was also ambivalent about her place in the world as a woman, finding it difficult to reconcile her desire for independence and her inclination to write with her own Victorian values. Over the course of her life, however, independence became her predominant desire, one she ultimately achieved through writing.

According to Larrabee, this ambivalence was displayed in her use of a pseudonym, Enna Duval, at the start of her writing career. Between 1845 and 1849, Brewster published at least twenty-two short stories. All her protagonists were women, and the stories shared a common theme: “Marriage brings happiness only if one marries for love, not financial security,” (Larrabee, p. 11). In 1849, she published her first book, a novella titled Spirit Sculpture, and her first poem, “New Year Meditation,” was published in Graham’s Magazine. After the publication of “New Year Meditation,” she was hired by Graham’s as an editor, a post she held until 1851.

It was after Anne’s father died in 1854 that she began her efforts for financial independence in earnest. Maria Hampton Brewster, her mother, died the year before, a tremendous personal loss for Anne. Maria left Anne her entire estate, per an understanding with her husband that stated Maria could dispose of her pre-marriage assets as she saw fit. However, Anne’s father reneged on the agreement, and left his entire estate, including Maria Hampton Brewster’s assets, to his two illegitimate sons. Anne’s brother, Benjamin, eventually convinced his half brothers to share the inheritance. Benjamin, however, retained control of Anne’s share. Completely dissatisfied with this arrangement, Anne took her brother to court. They battled in court for years; Anne eventually lost and Benjamin retained control of her inheritance.

Despite these legal issues, the 1850s proved a successful and exciting decade for Brewster. To begin with, between 1851 and 1857, she published four short stories. Then in 1857, leaving the matter of her lawsuit in the hands of a friend and lawyer, Charles F. Thomas, Brewster traveled to Italy and Switzerland. In Europe, she spent her time reading, writing, and studying French, German, and Italian. She returned to America in August of 1858, settled in Bridgeton, New Jersey, and supported herself by writing and teaching music and French. In 1859, Brewster wrote and published numerous short stories in Harper’s Magazine, The Atlantic Monthly, "Peterson’s Magazine" , Dwight’s Journal of Music and The Knickerbocker. She also published the novel Compensation. By this time, she had more confidence in her writing and abandoned use of her pseudonym. In 1866, she published her second novel, St. Martin’s Summer.

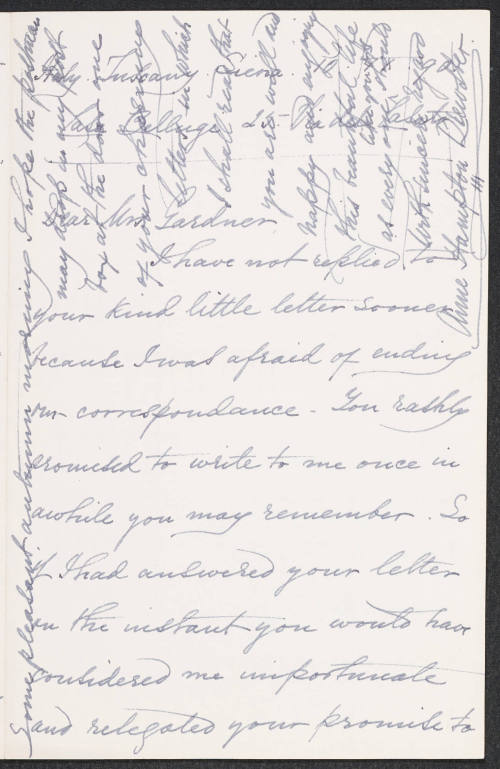

In 1868, Brewster returned to Italy, where she would stay for the rest of her life. To help support herself in Rome, Anne wrote weekly or monthly articles about Italian art, architecture, archaeology, political events and social gossip for American newspapers. Most notably, she wrote for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and Boston Daily Advertiser. Her newspaper articles gained attention, and she became prominent in artistic circles in Rome. She hosted a weekly salon where she entertained other famous writers and musicians of the day, and she developed close relationships with many of them.

Brewster was able to fully support herself in Italy, though she was not without financial worries. Income generated from her inheritance fluctuated from year to year, and in some years she needed to write more to compensate. Then, in the 1880s, she began to lose her newspaper engagements. Journalism in America was changing, and her contributions as well as her writing style were becoming antiquated. Her financial situation forced her to move to Sienna, Italy, where it was significantly less expensive to live. Though she missed Rome, she remained in affordable Sienna, still valuing her independence above all else. While there, she published one last article in the magazine Cosmopolitan, about her life in Sienna. She died in 1892.

Bibliography:

Larrabee, Denise M. Anne Hampton Brewster: 19th Century Author and “Social Outlaw”. Philadelphia: Library Company of Philadelphia, 1992.

For a more detailed description of Anne Hampton Brewster’s life and this collection, Larrabee's entire article is available through Google books at: http://tinyurl.com/23oycvg

http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/pacscl/LCP_LCPBrewster

Brewster, Anne Hampton (29 Oct. 1818-1 Apr. 1892), fiction writer and foreign correspondent, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Francis Enoch Brewster, an attorney, and Maria Hampton. She and her family were middle-class Anglo-American Protestants. Her older brother, Benjamin Harris Brewster, became attorney general of the United States from 1881 to 1885. She was primarily educated by her mother, receiving little formal education.

Despite several suitors, Brewster never married. In 1845 she wrote in her journal, "I am not dependent. I have mind enough & strength to take care of myself. . . . I will never marry for mere convenience." Brewster's attitude toward marriage may have been influenced by her father's abandonment of the family in 1834, when he began living with his mistress, Isabella Anderson, and two illegitimate sons. Anne Brewster and her mother became financially dependent on Benjamin.

Brewster's interest in writing began with poetry, which she wrote freely until 1837, when Benjamin discouraged her. She resumed writing poetry in 1843 with the encouragement of Charlotte Cushman, who managed Philadelphia's Walnut Street Theatre. Brewster regained her confidence as a writer in this supportive relationship and began incorporating verses into short fiction she started publishing in 1845 under the pseudonym "Enna Duval." During her lifetime, she published fifty-two short stories that, like most nineteenth-century American woman's fiction, maintain that marriage for financial security is worse than remaining unmarried. Brewster abhorred economic dependency and believed that all women could develop the Victorian qualities of hard work, morality, and social responsibility in order to find happiness.

In 1848 Brewster converted to Catholicism. In her journal of that year Brewster maintains that "stern, strict duty" is necessary for one's own well-being. Catholicism had a prescribed role for Brewster, which she defines in her first book Spirit Sculpture (1849), a moderately successful novella concerning religious conversion: " . . . our [women's] duty lies in a silent performance of the virtues of self-denial, self-control, and the willing performance of the most disagreeable home duties, that we may thereby show the influence of the blessed faith we profess" (p. 94)." A review in Brownson's Quarterly Review stated that the novella showed "fine taste, very considerable powers, and much facility on the part of the author." But a harsh critic in Baltimore called the book "heresy" and described Brewster as "a young convert with some presumption." That same year, Brewster's first published poem, "New Year Meditation," appeared in Graham's Magazine, where she secured a position as an editor in March 1850. This appointment lasted until May 1851, resulting in numerous published pieces and a $500 yearly salary.

When Maria and Francis Brewster died in 1853 and 1854, respectively, the entire estate was split among Francis's three sons. Benjamin planned to support his sister indefinitely, but she sued him for a portion of the estate in 1856, maintaining that he was a tyrannical alcoholic. The court case and Benjamin's recent marriage, of which Brewster disapproved, prompted her to spend fifteen months in Vevey, Switzerland, and Naples, Italy, beginning in May 1857. On her return to America, she settled in Bridgeton, New Jersey, supporting herself by writing and teaching music and French. Brewster did not win the case but gained control of her rental property and would receive interest on the investments of the family estate that Benjamin controlled. She disapproved of this arrangement, became permanently estranged from Benjamin, yet depended on this variable income for the rest of her life.

Brewster abandoned her pseudonym in 1860 and published her second novel, Compensation; or, Always a Future (1860), which was successful enough to warrant a second edition in 1870. The story, set in Switzerland, is similar to her short fiction, with the addition of discourse on art, music, nature, literature, philosophy, and religion, drawn heavily from the personal journals Brewster had kept during her trip to Europe. Her third and last novel, Saint Martin's Summer (1866), is a narrated travel journal from Switzerland to Naples and explores the superiority of spiritual to physical love. The novel was both praised and criticized for its extensive descriptions.

Brewster's decision to move to Rome in 1868 was fueled not only by a desire to distance herself further from Benjamin, but by the tradition of Italian travel common among American writers and artists in the nineteenth century. With unreliable income from her inheritance, Brewster needed a more profitable vocation than fiction writing and accepted her first newspaper engagements in 1869 with the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin and the Newark Courier. During her first ten years in Rome, Brewster worked relentlessly to establish herself in her profession, becoming one of the earliest female foreign correspondents to the United States. Brewster reported on such significant events as the excavations of the imperial palace on the Palatine and Pius IX's announcement of the doctrines of papal infallibility. She was forbidden to enter the Vatican for three years because of her liberal account of Victor Emmanuel's troops entering Rome in 1870. In her report to the Newark Courier, Brewster described the pontifical police as "severe." She stated that the Romans saw the Italian troops as liberators and welcomed them enthusiastically with cries of "I nostri fratelli" (our brothers). Throughout her nineteen years in journalism she wrote for at least twelve American newspapers, including the Boston Daily Advertiser, the New York World, the Chicago Daily News, and the Cincinnati Commercial. She not only reported on the political, religious, and scientific events in Rome but the cultural ones as well, giving publicity to the artistic, literary, and musical accomplishments of her friends and acquaintances. Her interest in culture resulted in the publication of several articles in Lippincott's Magazine and Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. She was a member of Arcadia, the poetical academy in Rome, and held a weekly salon where she entertained writers, sculptors, painters, and musicians, including Sarah Jane Lippincott, William Wetmore Story, Emma Stebbins, and Franz Liszt. She had a platonic relationship with Philadelphia sculptor Albert E. Harnisch and shared a residence with him from 1871 to 1885.

During the 1880s, income from Brewster's inheritance dropped considerably, and her journalism career declined as newspapers required more concise news items. In 1889 she moved to Siena, Italy, in order to meet her expenses without additional income from writing. Still, she wrote her last article, "Siena's Medieval Festival," while living there and published it in the Cosmopolitan in 1890. She died in Siena, leaving several writing projects unfinished, including a revised collection of her newspaper correspondence from Rome between 1868 and 1878. Brewster believed her newspaper work was "elevating and beneficial--it confers a double benefit on myself and others." This accounts for the unique combination of gentility, self-revelation, and scholarship that endeared Brewster to her audience and made her one of the most popular foreign correspondents of the time.

Bibliography

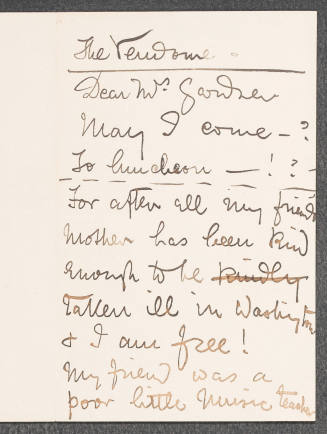

The Anne Hampton Brewster Manuscript Collection belongs to the Library Company of Philadelphia. It contains personal incoming correspondence, journals, commonplace books, copybooks, miscellaneous article drafts, clippings of Brewster's newspaper correspondence, reviews of her novels, and obituaries of friends and family. The Lloyd P. Smith Papers, also at the Library Company, contain outgoing correspondence. See also Estelle Fisher, A Gentle Journalist Abroad: The Papers of Anne Hampton Brewster in the Library Company of Philadelphia (1947); Nathalia Wright, American Novelists in Italy: The Discoverers--Allston to James (1965); and Denise M. Larrabee, Anne Hampton Brewster: Nineteenth-Century Author and "Social Outlaw" (1992).

Denise M. Larrabee

Citation:

Denise M. Larrabee. "Brewster, Anne Hampton";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-03248.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:42:28 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Auburn, Maine, 1876 - 1963

Boston, 1846 - 1924, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England

Steventon, England, 1775 - 1817, Winchester, England