Harriet Goodhue Hosmer

Watertown, Massachusetts, 1830 - 1908, Watertown, Massachusetts

found: Sherwood, D. The life of Harriet Hosmer, 1987: CIP t.p. (Harriet Hosmer)

found: NUCMC data from Boston Public Library for Gould, E.P. Papers, ca. 1876-1906 (Hosmer, Harriet Goodhue, 1830-1908)

found: Women's hist. sources, 1979 (Hosmer, Harriet Goodhue; 1830-1908; sculptor, originally of Watertown, Mass.; spent much of life working in Rome)

found: The Freedmen's monument to Abraham Lincoln, 1866: p. 3 (Harriet Hosmer; H.G. Hosmer)

Hosmer, Harriet Goodhue (9 Oct. 1830-21 Feb. 1908), sculptor, was born in Watertown, Massachusetts, the daughter of Hiram Hosmer, a physician, and Sarah Grant. Sarah Hosmer died when her daughter was four years old. Hiram Hosmer raised Harriet, providing her with physical and intellectual training well beyond the limits imposed on most middle-class girls of the time. Hosmer grew up renowned in her community for fearlessness and unconventional behavior, especially in regard to outdoor sports involving riding and shooting.

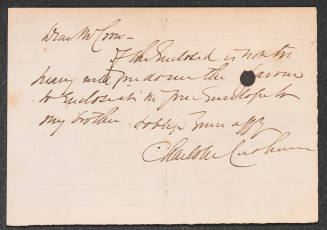

Courage in pursuing her goals and disregard for orthodoxy marked her academic life and her artistic career. When as an aspiring artist in 1850 she desired to obtain a knowledge of anatomy, she determinedly went to live with an old schoolmate and studied at Washington University, St. Louis, having been denied entrance to Boston area medical schools. Back in Watertown, she laboriously carved a bust of Hesper (Watertown Free Public Library), and when she went to Rome in 1852 she used it to persuade the British neoclassical sculptor John Gibson to accept her as a student in his studio. She became a well-known sight around the city, for she wore her hair--and sometimes her skirts--short, rode her own horse wherever and whenever she pleased, and frequently carried pistols or a steel-tipped umbrella for protection. A member of the actress Charlotte Cushman's circle of sophisticated professional women, Hosmer lived a strikingly independent existence.

Early scholars of her work tended to minimize the relationship between her mode of life and the subject matter of her strongest work, such as the life-sized figures of the tragic heroines Beatrice Cenci (1853-1855, St. Louis, Mo., Mercantile Library) and Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra (c. 1857, Hartford, Conn., Wadsworth Atheneum). Instead, thanks in part to pages in Nathaniel Hawthorne's Marble Faun (1860) and Passages from the French and Italian Notebooks (1871), condescending perceptions of Hosmer's spirited personality as "cute" mixed with the era's generally patronizing attitude toward women artists, creating the image of a "tomboy" maker of frivolous or derivative sculpture. Conceits such as the frequently replicated Puck (1856, Washington, D.C., National Museum of American Art) and Will-o'-the-Wisp (n.d., Piermont, N.Y., private collection), brought Hosmer attention from the highest circles of European society and formed the basis of her income. Small and charming, if arch, putti, these conceits must have appeared to be the very embodiment of "women's work" in sculpture. In contrast, the neoclassic Sleeping Faun (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts), exhibited in Dublin in 1865 almost as soon as it left the artist's studio, won instant acclaim for the muscular strength and beauty of the sleeping young man/animal.

Hosmer's recognition in the United States never attained the heights of popularity she reached among the international set in Europe. Derided for using male assistants to carve the marble versions of her clay models--in fact a common practice for all nineteenth-century sculptors of marble--Hosmer fought back in "The Process of Sculpture," published in the Atlantic Monthly (Dec. 1864), but her reputation was at least temporarily tainted. One of the few American sculptors who actually could carve, Hosmer produced a body of work known for its sensitive handling of drapery and anatomy, its clarity of design, and its highly polished yet delicate surfaces. Her moving images of youth are epitomized in her monument to Judith Falconnet in San Andrea delle Fratte, the first commission awarded to an American sculptor in a Roman church. Art historical scholarship on Hosmer during the latter part of the twentieth century has concentrated on iconographic features of her work and on the exemplary aspects of her career in relation to the history of women artists. She is frequently grouped with other American women sculptors who worked in Italy, such as Louisa Lander, Emma Stebbins, and Edmonia Lewis, but the quality of her work, from an artistic and technical standpoint, places Hosmer on a level of her own. She died in Watertown, Massachusetts.

Bibliography

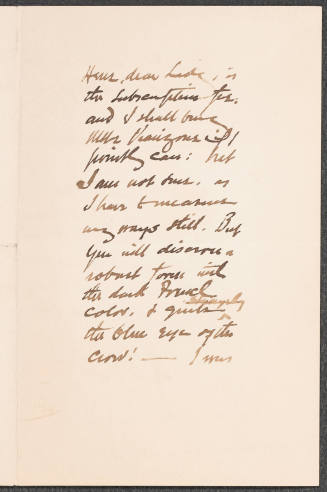

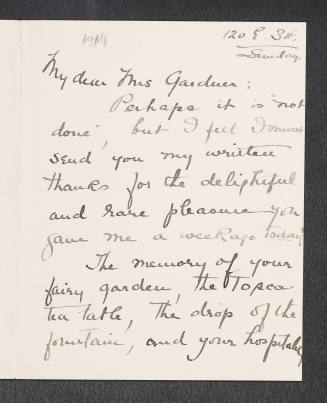

Hosmer's correspondence and reminiscences can be found in Cornelia Carr, ed., Harriet Hosmer: Letters and Memories (1913). An early biographical essay by Ruth Bradford, "The Life and Works of Harriet Hosmer," New England Magazine 77/n.s. 14 (Aug. 1871): 245-46, has been superseded by Dolly Sherwood, Harriet Hosmer: American Sculptor, 1830-1908 (1991). For Hosmer in context, see also Margaret Thorp, The Literary Sculptors (1965), and Joy Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives (1990).

Barbara Groseclose

Back to the top

Citation:

Barbara Groseclose. "Hosmer, Harriet Goodhue";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00425.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:32:51 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Salem, Massachusetts, 1819 - 1895, Vallombrosa, Italy

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1936, New York

Philadelphia, 1819 - 1892, Siena, Italy

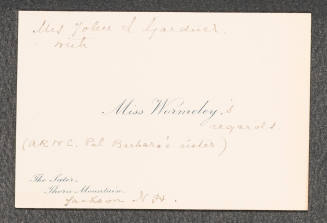

Ipswich, Suffolk, 1830 - 1908, Jackson, New Hampshire

Exeter, New Hampshire, 1850 - 1931, Stockbridge, Massachusetts