Henry James, Sr.

Albany, New York, 1811 - 1882, Boston

Although his teachers in Albany included the physicist Joseph Henry, James came to regard his formal education as ill conceived and irrelevant. He attended Union College and after five rather mediocre terms was allowed to graduate in 1830. Afterward, in obedience to his father's demands, he made a feint at studying the law but soon abandoned this career and took to drinking and gambling, a pattern followed by some of his younger brothers, one of whom (John Barber James) lost large amounts of money at faro in the 1850s and committed suicide.

At the age of twenty-three James underwent a powerful conversion, joined his parents' Presbyterian church, and entered Princeton Theological Seminary with the aim of becoming a minister. After about two years at this seminary, then staunchly Calvinist, James became convinced that modern Protestant denomination had deviated from gospel purity. He left Princeton and edited Robert Sandeman's Letters on Theron and Aspasio (1757), a fierce attack on the institution of the clergy. He also wrote a pamphlet, The Gospel Good News to Sinners, that sought to correct the errors of his Presbyterian teachers by setting forth a strict construction of sin, regeneration, and justification by faith. In 1840, following the practice of Sandeman's British followers, James was married in a civil ceremony to Mary Robertson Walsh.

Spending his early married years chiefly in New York and Albany, James seems to have devoted his time to private study. His literal approach to Scripture and his essentially Calvinist beliefs were not compatible with the Transcendentalist modes of thought then coming into vogue, and he was soon involved in a major new religious and intellectual crisis, stimulated in part by Ralph Waldo Emerson's 1842 lecture series in New York. Emerson put James in touch with Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller and in other ways introduced him to a wider and less parochial world of thought. James regarded Emerson as the first candid truth-seeker he had known, and Emerson pronounced James "the best apple on the tree."

In the spring of 1843 James tried to articulate his new nonliteral religious ideas in a series of lectures entitled "Inward Reason of Christianity." But he lost his audience and had trouble turning the lectures into a book, and when his health became unsteady, he decided to sell his home in New York and go abroad for a year. In London he became acquainted with Thomas Carlyle and John Sterling. Midway through the year, he was incapacitated by a psychic collapse. He apparently sought treatment at Sudbrook Park, a recently established hydropathic institution just east of London, but the baths and showers did little to alleviate his distress. A lady living in the vicinity, Mrs. Sophia Chichester, advised him that he was undergoing what Emanuel Swedenborg called a vastation--a laying waste, a making void. Convinced that his breakdown was part of a necessarily painful regenerative process, James appropriated some of Swedenborg's ideas in order to reconstruct his earlier Calvinism. He fixed on an allegorical method of biblical interpretation and worked out a universalized conception of the spiritual life.

James's first two children, William James and Henry James (1843-1916), had been born shortly before his trip to England. The last three--Garth Wilkinson, Robertson, and Alice James--were born after his return. Recovering from his breakdown and residing chiefly in New York, James decided to pursue a career as writer, lecturer, and public philosopher. Simultaneously, he was drawn to the thought of Charles Fourier, whose American followers were then starting up numerous communes or "phalansteries." In the fall of 1847 James became associated with the leading Fourierist magazine in America, the Harbinger, to which he contributed articles and reviews on an almost weekly basis. He also translated a French pamphlet, Love in the Phalanstery, which set forth the various alternatives to marriage that Fourier had advocated. Conservative opinion saw this pamphlet as an attack on the family. In the ensuing controversy James expressed views that anticipated the free-love movement of the 1850s: "If society left its subject free to follow the divine afflatus of his passion whithersoever it carried him, we should never hear of such a thing as sexual promiscuity or fornication."

The lectures James delivered in New York City from 1849 to 1851 proved to be the most daring, attention getting, and vigorous of his career. Brought out as books--Moralism and Christianity (1850) and Lectures and Miscellanies (1852)--they show James at his most assertive and outspoken. "Nature and society," he insisted, "should have no power to identify me with a particular potato-patch and a particular family of mankind all my days." Free self-expression, the imminent perfection of society, and the plastic nature of reality were among his major themes.

In 1852 James began to qualify his revolutionary and romantic assertions. Instead of anticipating new and relaxed forms of marriage, he pronounced monogamy a necessary discipline in the life of man. Opposed to the early feminist movement, he declared woman to be an intellectually limited being who humbly served man even as she enabled him to transmute his selfish brutality into more social uses. James's next few books tended to address narrow readerships rather than the cultivated general public. The Church of Christ Not an Ecclesiasticism (1854) insisted that Swedenborg did not intend to found a new denomination. The Nature of Evil (1855), a lengthy rejoinder to a book by Rev. Edward Beecher, developed the idea that man's sense of individual agency was his one great sin. Christianity the Logic of Creation (1857) argued that the Bible was a sort of hieroglyphic of the founding principles of human selfhood.

In 1850 James became an occasional contributor to the New York Tribune. His essays pushing for more liberal divorce laws led to his involvement in a controversial exchange on marriage and free love that saw print under the title Love, Marriage, and Divorce (1853). His contributions often focused on topics of the day--spirit-rapping, alcoholism, theological controversies, and various contemporary scandals and crimes. In 1855 he wrote some hard-hitting editorials supporting the suppression of New York's gambling establishments. He also sent the Tribune a long series of letters on affairs in Switzerland, France, and England. However, Horace Greeley, the Tribune's owner and editor, felt that James was too impractical and paradoxical, and a dispute between the two men brought James's contributions to an end in 1859.

Between 1855 and 1860, James and his family resided in Europe for two extended periods. His chief purpose in going abroad was to provide his children, William in particular, with a better education than seemed available in the United States. The children attended schools in Geneva, London, Paris, Boulogne, and Bonn, had English and French tutors and governesses, and learned French and German. James himself made no significant new contacts and lost touch with political and intellectual currents in the United States. His closest friends and correspondents tended to be former radicals who had settled into lives of comfortable alienation. He became more genial, relaxed, and home loving.

Although James had not been an abolitionist, he strongly supported the Union side when the Civil War broke out. He saw the war as heralding an apocalyptic transformation of human life, and in an 1861 Fourth of July oration that may well be his most widely known work, "The Social Significance of Our Institutions," he contrasted the United States with Europe and celebrated the sentiment of human equality in American history. But equality was less a political than a spiritual concept for James, and at war's end he confided to an old friend, Parke Godwin, that "democracy is the crowning invention of human stupidity."

Moving to Boston in 1864 and then, two years later, to Cambridge, where he bought a house bordering Harvard Yard, James became a sort of brilliant excrescence of Brahmin New England. He belonged to the Saturday Club, frequented and sometimes addressed the Radical Club, spoke to the New England Women's Clubs, and occasionally attended the Examiner Club, which had a strong Unitarian presence. He was an occasional contributor to the Atlantic Monthly, the North American Review, and the Nation. In 1874 a confidential letter of his on marriage and divorce was published in a radical free-love periodical, Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, and he became embroiled in an embarrassing public exchange. Perhaps his most successful productions were his lively reminiscences of Carlyle and Emerson.

James's last three books were Substance and Shadow (1863), The Secret of Swedenborg (1869), and Society the Redeemed Form of Man (1879). In these works James restated and re-argued his fundamental idea, which he called creation--the tortuous process by which absolute spiritual reality replicates itself. In defending his system, James often abused other philosophers, saying of Immanuel Kant: "I for my part do not hesitate to profess my hearty conviction that he was consummately wrong, wrong from top to bottom, wrong through and through, in short all wrong." James's son William is said to have designed a humorous frontispiece for Substance and Shadow that showed a man beating a dead horse. Asked for his opinion of The Secret of Swedenborg, William Dean Howells is supposed to have declared that James "kept it."

Those who knew James were impressed by his intellectual energy, his unrestrained and often intemperate manner, his explosive humor, and his evident self-contradictions. Many objected to his high-handed absolutism; some considered him remarkably humble. Most saw him as both obscure and doctrinaire. He did not force his system on his children, but they absorbed its leading features--the aversion to respectable "moralism," the conviction that mundane or despised things had a deep significance. Perhaps James's greatest achievement was to energize his children's minds, exposing them to a wide range of experience and at the same time persuading them to refuse standard categorizations, allegiances, assessments. Yet if William, Henry, and Alice's relative freedom from the shibboleths and maxims of their time may be attributed to their father, it is also the case that his extraordinary ambiguities led these children to leave certain aspects of their own lives unfaced and unexamined. For good and bad, James was the creative force responsible for one of the most brilliant and productive families in American life. He died in Boston.

Bibliography

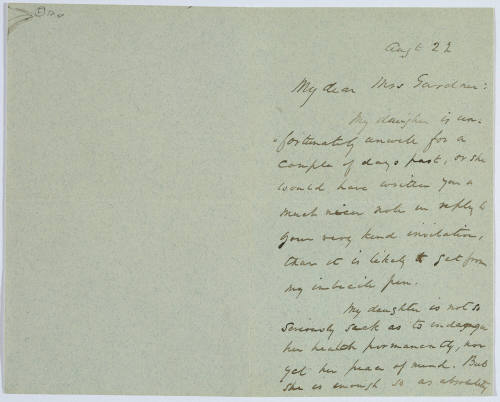

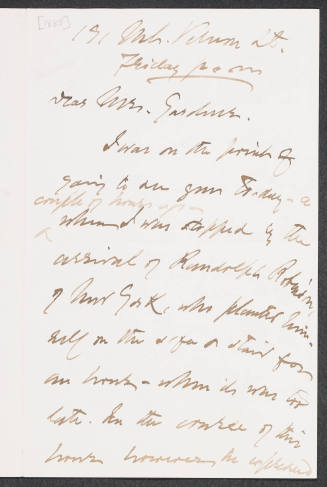

Most of James's papers are in the Houghton Library at Harvard University. There are also holdings at Amherst College, Union College, and Colby College. His heavily marked Swedenborg books are in Newton, Mass., at the Swedenborg School of Religion. The only known copy of The Gospel Good News to Sinners is at the New-York Historical Society. His correspondence with Joseph Henry has been published in The Papers of Joseph Henry, ed. Nathan Reingold (1972-). There are two biographies: Austin Warren, The Elder Henry James (1934), and Alfred Habegger, The Father: A Life of Henry James, Sr. (1994). Jean Strouse, Alice James (1980), and Howard M. Feinstein, Becoming William James (1984), offer helpful biographical interpretations of James in relation to two of his children. Chapter 6 of Henry James, Jr.'s memoir, Notes of a Son and Brothers (1914), gives a vivid evocation of James.

Frederick Harold Young has written a sympathetic interpretation of James's thought in The Philosophy of Henry James (1951). Shorter but well-informed interpretations are in Julia A. Kellogg, Philosophy of Henry James (1883); William James's introduction to his edited volume, The Literary Remains of the Late Henry James (1885); Ralph Barton Perry, The Thought and Character of William James, vol. 1 (1935); and Quentin Anderson, The American Henry James (1957). Raymond H. Deck, Jr., discusses James's relation to Swedenborgian thought in "The 'Vastation' of Henry James, Sr.," Bulletin of Research in the Humanities 83 (Summer 1980): 216-47, and Alfred Habegger treats his relation to Calvinist thought in "Henry James, Sr., in the late 1830s," New England Quarterly 64 (Mar. 1991): 46-81, and his teachings on women and sexuality in Henry James and the "Woman Business" (1989).

Alfred Habegger

Back to the top

Citation:

Alfred Habegger. "James, Henry";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00842.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:41:57 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Florence, 1856 - 1925, London

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1817 - 1881, Boston

Dunbartonshire, Scotland, 1800 - 1859, London

Cambridge, 1827 - 1908, Cambridge