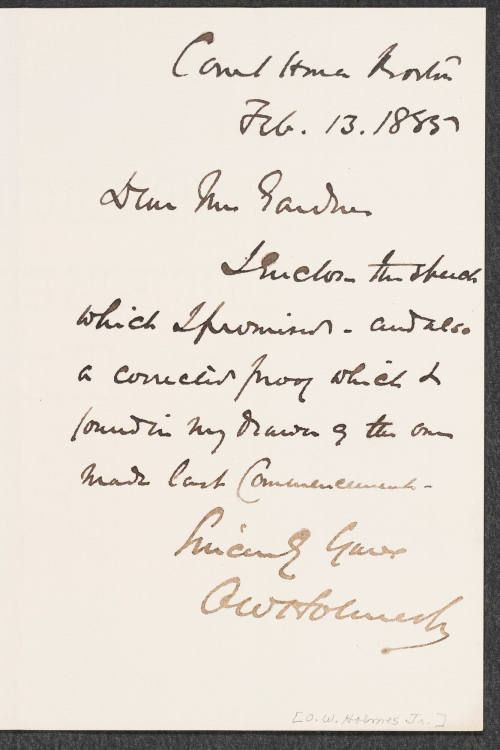

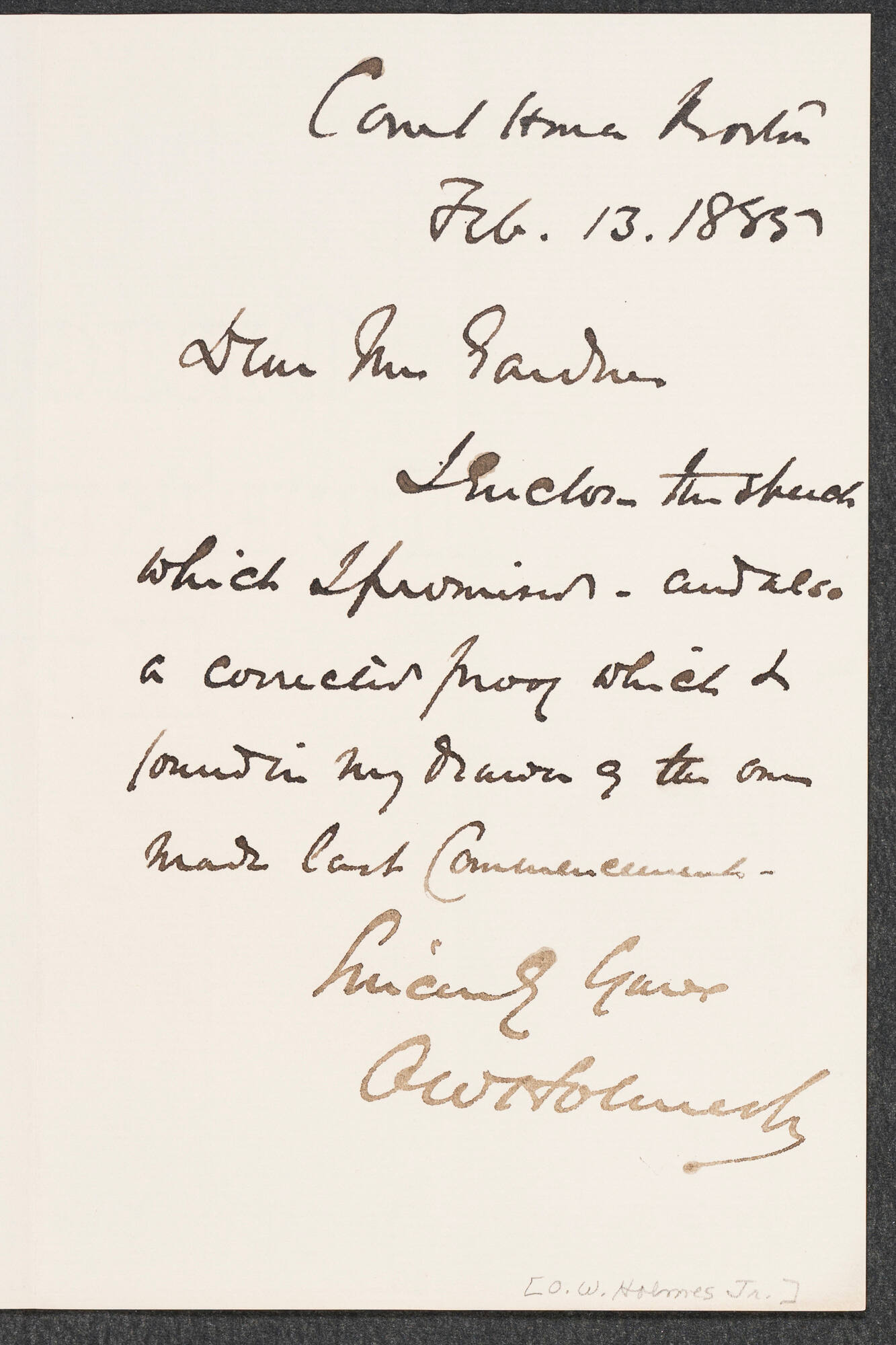

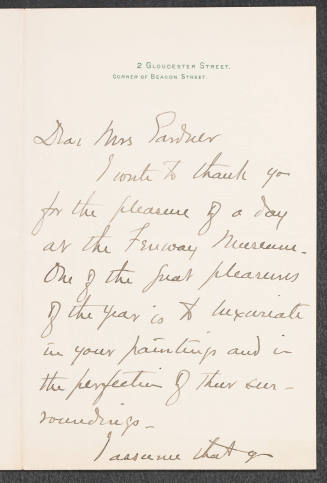

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Boston, 1841 - 1935, Washington, D.C.

In undergraduate essays, Holmes announced the need for a "rational" explanation of duty, a sort of scientific substitute for religion that he sought in an evolutionary account of both history and philosophy. Duty, he came to believe, was a moral instinct that was the highest expression of human evolution.

The other great influence on Holmes's youth was a revival of chivalry then sweeping over the United States and Great Britain, partly inspired by the writings of Alfred, Lord Tennyson and Sir Walter Scott. Like many of his contemporaries and with his mother's encouragement, Holmes absorbed courtly ideals and conduct. Chivalry was the code of duty for which he sought, and ultimately believed he had found, scientific justification.

Holmes's Evolutionist Philosophy

After the outbreak of the Civil War in the spring of 1861, Holmes enlisted in the Massachusetts militia, eventually obtaining a commission as a lieutenant. He served for two years in the Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and fought at Ball's Bluff, the Peninsula campaign, and Antietam. In those first two years he was promoted to captain, was wounded three times, twice nearly fatally, and suffered from dysentery. Exhausted, he completed the third and final year of his enlistment, in the winter of 1863-1864, as aide to General Horatio G. Wright and then to General John Sedgwick of the Sixth Corps. In the relative leisure of winter quarters, Holmes turned to philosophical writing, developing from his combat experience a purely materialist evolutionism. History was shaped by the perpetual conflict of rival nations and races, he believed. Laws were written and governments established by the victors.

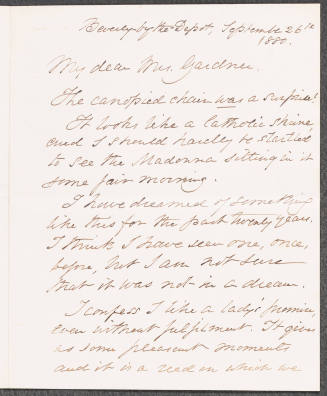

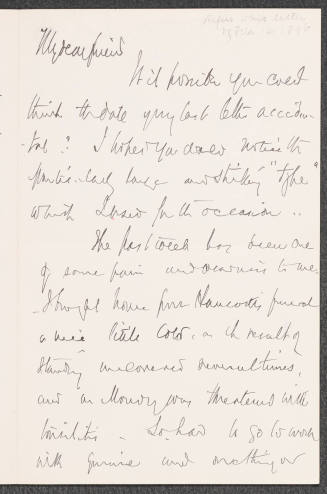

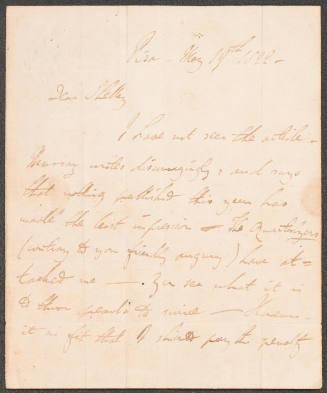

Holmes attended Harvard Law School (1864-1866) and, after receiving his degree in the summer of 1866, traveled to Great Britain and the Continent. He made a number of lasting friendships in Great Britain. One of the most important to him was with Leslie Stephen, who reinforced Holmes's commitment to an evolutionist philosophy, which they both believed would provide a scientific, materialist basis for the code of duty. Holmes returned to London whenever he could and kept up an energetic and extensive correspondence with British friends between visits. Many of these letters, published after his death, have become classics, helping to make Holmes a major figure in the history of American letters and thought.

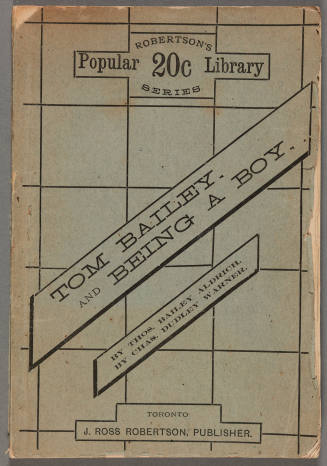

On his return to Boston, Holmes entered a law clerkship and was admitted to the bar in 1867. He then briefly gave up practice and attempted a career as an independent scholar and man of letters, editing the twelfth edition of Chancellor (of New York Courts) James Kent's Commentaries on American Law (1873) and writing dozens of brief articles and reviews for the newly formed American Law Review and occasional poetry for newspapers.

In 1872 Holmes married a childhood friend, Fanny Dixwell; they had no children. Unable to maintain a separate household on his meager earnings as a scholar, he abandoned scholarly pursuits and joined a Boston law firm that became Shattuck, Holmes, and Munroe with a busy commercial and admiralty practice. Fanny Holmes became seriously ill with rheumatic fever shortly after their marriage, and Wendell Holmes devoted himself to her and to his law practice for several years.

Holmes gradually returned to scholarly work in his spare hours, and in 1877, with "Primitive Notions in Modern Law" (American Law Review), he began a series of essays in which he attempted a systematic analysis of the whole of the common law--the judge-made law of Great Britain that in American courts still generally governed disputes between individuals. He completed the series somewhat hastily, gave them as the Lowell Lectures in November-December 1880, and published them as a book, The Common Law, in 1881, a few days before his fortieth birthday.

The Common Law (1881)

The Common Law, although hastily written and sometimes careless in its scholarship, is filled with novel insights and vivid imagery. Holmes's break with the a priori reasoning of the past is announced in the famous opening sentence: "The life of the law has not been logic, but experience." Despite its flaws, The Common Law has been called the greatest work of American legal scholarship. The central insight is that rules of behavior are not the fundamental data of law. Rather, law must be understood as a set of choices, often for unstated reasons, between possible outcomes.

In his earlier work, Holmes had labored unsuccessfully, like his predecessors, to untangle the dense mass of rules established by courts and legislature. In his first scholarly writings he had not been able to make a persuasive case for order or logic in this tangle of rules. In 1880, however, he had hit upon a new organizing principle. In cases of private law--suits for damages--judges decided which of the two parties would bear the burden of an injury. Holmes saw that the judge often found it easier to decide between the parties than to give a clear explanation or rule. The judge's written opinion, purportedly applying a rule, was often no more than a rationalization to explain the decision arrived at on other, sometimes unconscious, grounds. Instead of searching for preexisting principles of natural right or duty, therefore, Holmes turned his attention to the decisions of judges in particular circumstances. He argued that one could generalize from past decisions to predict the future behavior of judges. These empirical generalizations from the data of judicial behavior could be stated as rules or principles of law: "a legal duty so called is nothing but a prediction that if a man does or omits certain things he will be made to suffer in this or that way by judgment of the Court. . . . A man who cares nothing for an ethical rule . . . is likely nevertheless to care a good deal to avoid being made to pay money, and will want to keep out of jail if he can" ("The Path of the Law"). Holmes believed that, even when they contradicted a judge's self-justifying explanation, generalizations based on judges' behavior were the true principles of law and the basis on which the study of law could be made a science. Applying his new method, Holmes thought he had discovered a general organizing principle: modern judges would impose liability on a defendant when his or her conduct resulted in harm that an ordinary person would have foreseen. The injury and not the breach of a rule of conduct was the judge's central motive. Judges usually imposed liability on the blameworthy party, who in the modern world was the one who had caused foreseeable harm without adequate justification and who accordingly was felt to be responsible for the damage.

In The Common Law, Holmes traces the evolution of this principle of liability through the history of the law. Law, he argues, began as a substitute for private vengeance, as a means of controlling blood feuds. It then evolved into the instrument of a more highly civilized and complex moral system, in which punishment was imposed for moral culpability. As law continued to evolve in the nineteenth century, it was tending toward reliance on a single "external standard" that restricted personal liberty only to the extent necessary to prevent foreseeable harms. This evolution was driven by Malthusian forces. Only decisions that had contributed to the survival of the race would be preserved. It followed that law concerned itself solely with material aims and that law would continue to evolve until it was a fully self-conscious instrument of social purpose. The principles of a liberal, utilitarian policy of individual liberty and economic efficiency that Holmes found to be the often unstated motive of judicial opinions presumably had been favored by natural selection. Holmes's book itself, he plainly believed, was an important step in the evolution of the law toward self-awareness.

Although this theory of evolution through race and class struggle in which Holmes believed is now discredited, his turn toward the motives and actions of judges and away from formalistic rules of law marked an epoch that continues. Holmes's new methodology had a profound influence. He was considered one of the founders of sociological jurisprudence in Great Britain and the United States, of the school of legal realism that succeeded it, and still more recently of studies of law employing the tools of economics and rational choice analysis.

Appointment to the Supreme Court of Massachusetts

After The Common Law appeared, Holmes gave up his commercial practice and in the fall of 1882 taught for a few months at Harvard Law School. In December of that year he accepted appointment to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts and promptly resigned his professorship. He served on the state's highest court for twenty years, becoming chief justice in 1899.

Holmes wrote more than 1,400 opinions for the Massachusetts court, and in them he relentlessly worked through the thesis of The Common Law, thereby writing his theory into the law of Massachusetts. An incompetent doctor and an abortionist could each be tried for murder, he wrote for the court, because a person of ordinary foresight performing medical services would have known that the treatments provided, even if well intentioned, were likely to kill. Holmes's opinions, despite their harsh tone, influenced courts throughout the English-speaking world.

In the early years of his service on the Massachusetts court Holmes tried to avoid writing opinions in constitutional cases, with which he had had little experience as lawyer or scholar. When obliged to state a view, he usually expressed deference to the legislature, except when a statute had stripped away a person's right to a fair hearing. He based this deference on the English constitutional principle that the legislature was omnipotent, a principle he thought had been modified in the United States only to the extent that written constitutions contained clear limitations on legislative authority. This was the reasoning of Thomas Cooley's famous treatise Constitutional Limitations (1868), but it would have been a natural enough conclusion from Holmes's own approach to jurisprudence.

In 1894 Holmes made a major addition to his system of ideas with an article, "Privilege, Malice, and Intent," published in the Harvard Law Review. Here the focus is on libel and slander cases that had come before Holmes, in which liability was based, at least in part, on the defendant's state of mind--actual malice--rather than an objective or "external" standard of foreseeable harm. In these cases, which seemed to contradict his central thesis, Holmes argued that the rule of law was still based on prudent social policy. In certain cases a defendant might be privileged to do even foreseeable harm, however. Such a "privilege," like that accorded to a person for truthful speech, Holmes argued, afforded foreseeable benefits that would outweigh the foreseeable harm that it caused. Judges accordingly did not impose liability for harms caused by expressions of honest opinion. But a privilege would be withdrawn when used for the very purpose of causing harm, malicious motives presumably tilting the balance and making harms more likely than benefits. In 1896 he applied his revised theory in a dissenting opinion in Vegehlan v. Guntner, in which he argued that a privilege should be extended to trade unions to organize and picket peacefully, so long as these activities were carried on without malice, even though injury to their employer could be expected. (Somewhat confusingly, however, he justified the workers' privilege to picket on grounds of fairness, a similar privilege having been extended to employers; Holmes said that, on economic policy grounds, trade unions in themselves were not desirable.) Holmes's views on labor disputes were gradually adopted by his Massachusetts court and the U.S. Supreme Court, and they eventually were written into statute law in both the United States and Great Britain. His views on privilege generally proved to be more controversial but influenced the development of constitutional law, as we shall see.

Thoughts on Duty

In his early years as a judge, Holmes began to deliver public addresses modeled on Emerson's, in which he presented in carefully chiseled images his personal philosophy. Collected into a slim volume (Speeches, 1891-1913), these have become classics of the art and are frequently quoted. They provided Holmes the chance to answer the question of his youth: the sense of duty that had led him and so many others to risk their lives and thus seemed contrary to the instinct for survival was itself founded on an instinct, one of individual self-sacrifice in the interest of group survival, and hence was a part of the evolving natural order. The instinct at the root of duty defined the gentleman and was most strongly expressed in a relatively small number of men, officers in the endless war for control of scarce natural resources, men whose self-sacrificing determination would decide the survival of a race, class, or nation. These views were expressed most forcefully in his Memorial Day addresses, commemorating the Civil War, in 1884 and 1895. In later addresses he made the point that judges were expected to be gentlemen, scientist-scholars, like Holmes himself, trying to gauge how the conflicts of social forces would turn out, securing the future growth of civilization even at the expense of their own class interests.

In Holmes's earlier writings he had seemed to say that judges for the most part served as unconscious creatures of the dominant group from which they were drawn and their decisions would survive only to the extent they served the survival interests of the class from which they were drawn. Now a judge himself, Holmes said that judges were called upon by duty to sacrifice even their own class when this was required by a fair decision between contending parties. Their duty was to the human race itself. Having undergone a profound shift, Holmes's philosophy now seemed to be based more on a faith in the ultimate purposes of cosmic evolution than on the data of history; many commentators have remarked on the apparent contradiction between his early theories and his later work as a judge.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Beverly, Massachusetts, 1851 - 1930, Beverly, Massachusetts

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1809 - 1894, Boston

Horsham, 1792 - 1822, near Viareggio

Brighton, Massachusetts, 1839 - 1915, Boston

Preston, England, 1868 - 1936, London

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Cadiz, Ohio, 1846 - 1933, Royal Oak, Michigan

Cambridge, 1827 - 1908, Cambridge