Oliver Wendell Holmes

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1809 - 1894, Boston

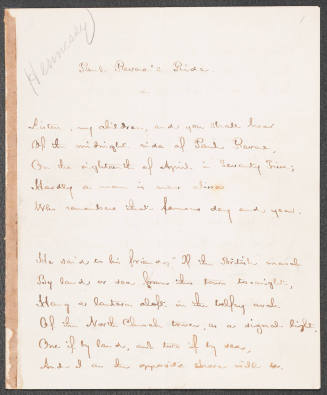

After graduating from Harvard in 1829, Holmes enrolled in the Dane Law School. Within a year, however, he became disenchanted with his studies, having, as he later wrote, "first tasted the intoxicating pleasure of authorship" with the publication of his poems in the Harvard Collegian and also in the Amateur and the New England Galaxy, both short-lived literary periodicals. Holmes won fame at age twenty-one with his hastily written "Old Ironsides," printed first in the Boston Daily Advertiser in 1830. A passionate plea against the planned scrapping of the frigate Constitution, famous from its service in the War of 1812, the poem was reprinted nationwide--even scattered about the capital in handbill form, like an Elizabethan broadside--and saved the antique warship from demolition. Notable also among Holmes's early writings are two essays printed in 1831 and 1832 in New England Magazine, both with the title "The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table," which Holmes would reuse twenty-five years later.

Holmes abandoned law for medicine in 1831, entering Boston Medical College, where he studied under James Jackson. After additional study at Harvard Medical School, Holmes traveled to Paris, then regarded as the world center for medical training. In "Some of My Early Teachers," Holmes wrote about some of his Parisian professors, such as one M. Lisfranc, who was given to "phlebotomizing fits," and especially Pierre Louis, who opposed wholesale reliance on therapeutic bleeding and whom Holmes credited with introducing quantitative methods to medical practice. While living in Paris, Holmes journeyed widely in western Europe, recording witty observations that would later appear in the Life and Letters of Oliver Wendell Holmes. He finally received his medical degree from Harvard in 1836 and entered private practice in Boston.

Although Holmes worked as a doctor for ten years, he became much more important as a medical writer and teacher than as a practicing physician. He won Harvard's Boylston Prize in 1836 for an essay on auscultation and percussion and again in 1837 for essays on the treatment of malaria and neuralgia. Holmes cofounded the Tremont Medical School, where he taught pathology and physiology and later also surgical anatomy. In 1838 he was appointed professor of anatomy at Dartmouth College, a post he held until his marriage to Amelia Lee Jackson in 1840. Amelia, daughter of Massachusetts supreme court justice Charles Jackson, was Holmes's second cousin, and the niece of his mentor James Jackson; the couple would have three children.

Meanwhile, Holmes's first book, Poems, had been published in 1836, and in 1838, at the recommendation of Ralph Waldo Emerson, he had begun to appear on the Boston Lyceum's popular lecture circuit. Although he was limited by his severe asthma from extensive travel, Holmes delivered entertaining and erudite lectures on science and literature that remained in high demand for decades and contributed substantially to both his celebrity and his income.

Holmes made his greatest contribution to medicine in 1843, with the publication of "The Contagiousness of Puerperal Fever" in the New England Quarterly Journal of Medicine and Surgery; the paper was originally delivered as a lecture before the Boston Society for Medical Improvement and was quickly reprinted in pamphlet form. Puerperal (or "childbed") fever was a feared, seemingly unpredictable, and often fatal complication of childbirth. Holmes compiled a "long catalogue of melancholy histories" as anecdotal evidence of the disease's infectiousness and supplemented this with a survey of the medical literature of France, England, and the United States. His case studies provide a vivid picture of the state of mid-nineteenth-century medical care before the advent of modern bacteriology. He denounced as typical, for example, one Dr. Campbell, who infected a newborn girl when he arrived at her mother's bedside directly from the dissection table, where he had conducted a postmortem on another victim of the fever, with the dead child's "pelvic viscera" in his pocket.

Holmes is generally credited with discovering the contagious nature of puerperal fever, though he cited other doctors who understood it as early as 1795. Holmes, however, decisively confronted American members of his own profession with their role in transmitting the illness. His work was corroborated in 1846 by a Hungarian doctor, Ignaz Semmelweiss, who was dismissed from his hospital for challenging established medical practices. Holmes was likewise vilified in pamphlets by two leading Philadelphia obstetricians, Hugh L. Hodge and Charles D. Meigs (published in 1851 and 1853, respectively), in response to which he reprinted his pamphlet with a new introduction in 1855. Eventually Holmes and Semmelweiss would be vindicated by the research of Joseph Lister and Louis Pasteur. Holmes's other medical publications include Homeopathy and Its Kindred Delusions (1842) and Medical Essays, 1842-1882 (1883).

In 1847 Holmes was appointed Parkman Professor of Anatomy and Physiology and dean of Harvard Medical School. His deanship was once marked by controversy, when he supported the admission of a woman and three African Americans to the school, only to accede to the threats and demands of the remainder of their class, thus barring the four students from further study. Although this incident suggests that Holmes held progressive views, albeit none too firmly, he was a lifelong conservative and a strident anti-abolitionist, who changed his opinion only with the outbreak of the Civil War and his elder son's enlistment in the Union army.

Holmes's tenure as dean ended in 1853. In 1871 the school reduced his responsibilities, reappointing him Parkman Professor of Anatomy, a post he held until 1882, at which point he became a professor emeritus, continuing as such until the end of his life. The sound training he had received in his Paris years and his extraordinary gifts as a lecturer sustained Holmes through thirty-five years of teaching. So skilled was Holmes that he was habitually assigned the school's last of five morning lecture slots, when the students were notoriously at their most restless. Salting his descriptive analysis with anecdote, imagery, and humorous wordplay, Holmes charmed his exhausted audience, never failing to earn, in the words of one of his students, "a mighty shout and stamp of applause" (Life and Letters, vol. 1, p. 176).

Not surprisingly, Holmes was also a renowned conversationalist, if somewhat vain, fond of flattery, and given to monopolizing the flow of talk. Along with such friends and fellow luminaries as the naturalist Louis Agassiz and the poet James Russell Lowell, Holmes reigned at the Saturday Club. Holmes's talents for talk at table and at the podium converged in a midlife renewal of his literary career that fulfilled the promise of his youthful efforts and propelled him to sudden success as a popular writer. Lowell made it a condition of accepting the editorship of the Atlantic Monthly in 1857 that Holmes should be secured as a founding contributor. The new magazine, which Holmes also christened, proved to be the ideal forum for his wit.

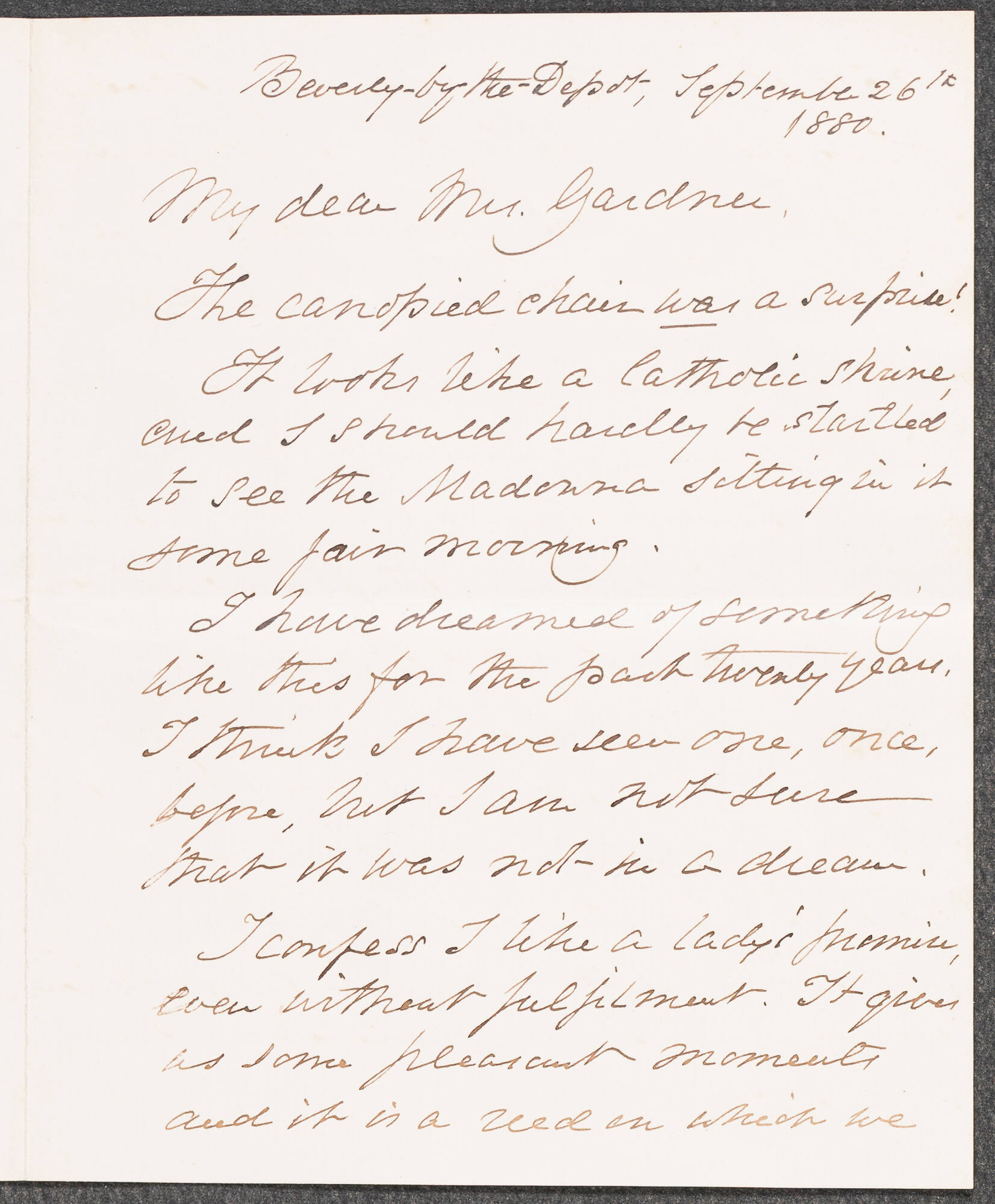

Although Holmes never allowed the original 1830s pieces called "The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table" to be reprinted in his lifetime, he revived the title for a popular series of conversational essays, collected in book form in 1858. Here for the first time Holmes the writer borrowed a favorite device from Holmes the orator, often concluding his display of anecdote, epigram, and chat with an original poem; some of his best verses, including "The Chambered Nautilus," appeared first in this manner. The more austere and contentious "The Professor at the Breakfast Table" series followed in 1859 (collected in 1860), and was in turn followed by "The Poet at the Breakfast Table" (collected in 1872). "Over the Teacups" (collected in 1891) finally concluded the sequence. Most critics have noted a steady decline in quality over the years; The Autocrat at the Breakfast Table remains the best of the collections, and contains Holmes's most characteristic prose.

Holmes's three "medicated" novels--the term was applied by a friend to the first of them--have worn less well (and moreover were not well received in their day). All three are case studies of abnormal psychic or physiological states for which the protagonists are not essentially responsible, and as such the novels can be read as allegorical critiques of the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, one of Holmes's favorite essayistic targets. (Holmes's free-thinking religious opinions, though highly controversial in their day, seemed harmless enough only a few decades later.) The first novel, Elsie Venner (1861), which was originally published as a serial in the Atlantic Monthly in 1859, traces the fate of a girl whose behavior is strangely influenced by a snake bite that her mother suffers prior to her birth. Despite Holmes's stated intent to "test the doctrine of original sin" and "inherited moral responsibility," the book is best remembered for a clear-eyed portrait of the New England aristocracy in its opening chapter, "The Brahmin Caste of New England." The Guardian Angel (1867), which also first appeared as a serial (in 1866), examines its heroine's ancestral psychological inheritance, while A Moral Antipathy (1885) concerns a man who is cured of a mysterious case of "gynophobia" by his encounter with a dominant female.

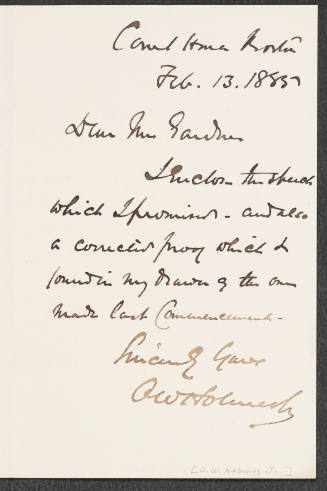

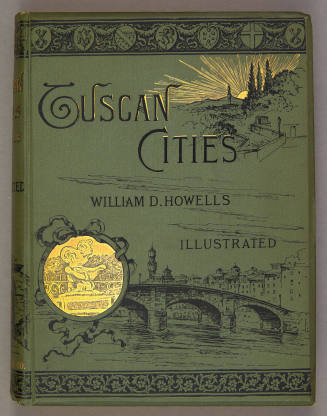

Holmes's many other prose works include two books of essays, Soundings from the Atlantic (1864) and Pages from an Old Volume of Life (1883), both mainly comprising pieces from the Atlantic Monthly; and two biographies, John Lothrop Motley: A Memoir (1879)--a portrait of a dear friend--and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1885), commissioned for the American Men of Letters series. His travel book, Our Hundred Days in Europe (1887), recounts a happy summer Holmes spent in Europe with his daughter, during which he received honorary doctorates at Oxford and Cambridge and revisited places he had known as a student a half century before. In "My Hunt after the Captain," first published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862, Holmes recounts his quest for his namesake son (Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.), who was wounded at the battle of Antietam. Holmes Jr. evidently felt that his father had exploited his ordeal for literary effect, a misunderstanding that contributed to the animosity that colored their relationship. One of Holmes's more idiosyncratic works is The Physiology of Versification (1883), a theoretical treatment of the connection between the laws of prosody and the laws of respiration and pulse.

Holmes's volumes of poetry, other than successively expanded editions of his 1836 Poems, include Songs in Many Keys (1862), Songs of Many Seasons (1875), The Iron Gate, and Other Poems (1880), and Before the Curfew, and Other Poems (1888). Editions of The Complete Poetical Works of Oliver Wendell Holmes appeared during his lifetime in 1887 and 1890. His best-known serious poems include "The Living Temple" (1858) and "The Last Leaf" (1833); his enduring light verse includes "The Height of the Ridiculous" (1830) and "Dorothy Q." "The Deacon's Masterpiece, or 'The Wonderful One-Hoss Shay' " (1858) is a humorous poem on a serious subject, in which the eponymous vehicle collapses all at once--a parable of the breakdown of Calvinism. For many years Boston's unofficial poet laureate, Holmes was also something of a professional Harvardian. A quarter of his 400-odd poems relate to his alma mater, many composed as light after-dinner vers d'occasion.

In his energetic and self-confidant pursuit of multiple careers, Holmes is a representative figure of the nineteenth century--even though Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., seems to have considered his father a dilettante. The effortless social fluency that allowed Holmes so to dominate his peers ultimately confined him, too. His inherent parochialism has limited his intellectual influence and denied much of his published work the grace of transcending its time and place. Holmes finished editing the Riverside edition of his collected works in 1891. He died at his house in Boston three years later.

Bibliography

The Writings of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Riverside Edition (13 vols., 1891-1892), which contains all the works discussed above, remains standard. The edition of The Complete Poetical Works of Oliver Wendell Holmes edited by Horace E. Scudder (1908) omits "Urania," a controversial poem with anti-abolitionist overtones. John T. Moore, Life and Letters of Oliver Wendell Holmes (2 vols., 1896), is a biography incorporating a large amount of Holmes correspondence. Edwin Palmer Hoyt, Improper Bostonian: Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes (1979), is a sympathetic portrait. Liva Baker offers an interesting account of Holmes's ancestry and suggestive speculation about his influence on his son, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., in her Justice from Beacon Hill: The Life and Times of Oliver Wendell Holmes (1991). Miriam Rossiter Small's Oliver Wendell Holmes (1962), in Twayne's Famous American Authors series, suffers from frequent biographical inaccuracies. Clarence P. Oberndorf proposes that Holmes's novels anticipated modern psychology but takes the thesis to often comic extremes in his The Psychiatric Novels of Oliver Wendell Holmes (1903). Also worth consulting are Samuel McChord Crothers, Oliver Wendell Holmes: The Autocrat and His Fellow Boarders (1909), and Mark Anthony DeWolfe Howe, Holmes of the Breakfast Table (1939).

The Editors

Online Resources

Illustrated Poems of Oliver Wendell Holmes

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa;idno=ABX8133

Complete page images from Illustrated Poems of Oliver Wendell Holmes (1885); part of the Cornell/Michigan Making of America project.

Back to the top

Citation:

The Editors. "Holmes, Oliver Wendell";

http://www.anb.org/articles/12/12-01980.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:23:56 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Boston, 1841 - 1935, Washington, D.C.

Boston, 1818 - 1890, Newton, Massachusetts

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1817 - 1881, Boston

Preston, England, 1868 - 1936, London

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1836 - 1907, Boston

Cadiz, Ohio, 1846 - 1933, Royal Oak, Michigan

Dorchester, 1808 - 1896, Marietta