Image Not Available

for Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Beardsley

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

LC Heading: Beardsley, Aubrey, 1872-1898

Biography:

Beardsley, Aubrey Vincent (1872–1898), illustrator, was born on 21 August 1872 at 12 Buckingham Road, Brighton, Sussex, the son of Vincent Paul Beardsley (c.1840–1909), and his wife, Ellen Agnus (1846–1932), the daughter of Surgeon-Major William Pitt and his wife, Susan.

Childhood

Beardsley's childhood was full of social instability and emotional intensity. His father was listed on the birth certificate as ‘gentleman’ because he had inherited a fortune, but soon after Aubrey was born he lost it. He found a job in London but was unconvincing as a breadwinner, and the Beardsleys lived in lodgings for the next twenty years, fending off poverty. His mother never forgave this fall from grace. She hugged her two children to her, cultivated their genteel talents in music and literature, and presented herself as the victim of a mésalliance. Perhaps the best love which Beardsley received as a child was from his older sister, Mabel.

At the age of seven Beardsley was found to have tuberculosis. This was not necessarily life-threatening, but he was a frail boy, ‘like a delicate little piece of Dresden China’ his mother said (Walker, 75), and there was always concern about his health. From twelve to sixteen he attended Brighton grammar school, where his fees were paid for by a great-aunt and where he made a place for himself as a pale and bookish outsider.

Beardsley left school in December 1888 and obtained a job as a clerk in London. It was a narrow existence: office work during the day, browsing in bookshops in his lunch hour, and browsing again on the way home to the family's lodgings in Pimlico. On Sundays the Beardsleys worshipped at St Barnabas, Pimlico, and sometimes the high-Anglican ritual there was the only note of colour in his week. He read modern French novels, particularly Balzac, and hoped to become a writer. Late in 1889 his tuberculosis erupted, and he bled from the mouth for the first time. About a year later he discovered the work of the painter and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and started to draw seriously, hoping to become an artist.

Early career

Beardsley spent the year 1891 learning about art, going to galleries and exhibitions, and seeking advancement. In June he went to Frederick Leyland's London house, 49 Prince's Gate, with its superb Pre-Raphaelite and old master paintings, and its Peacock Room decorated by J. McNeill Whistler. The Pre-Raphaelites were Beardsley's favourites at this stage, but he was alert to other current tastes: the New English Art Club, the French décadents, Oscar Wilde. And he was certainly ready to learn from Whistler about Japan, and the cult of personality. In July he went to see his then particular hero, Edward Burne-Jones, who praised his work and said he ought to go to art school. As a result, he attended Westminster School of Art in the evenings for about a year.

In January 1892 Beardsley had a visit from (W. H.) Aymer Vallance, a former high-Anglican clergyman who was now talent spotting as an art journalist. Vallance admired Beardsley's work and began to promote him—which was not difficult, because Beardsley had begun to create a public persona for himself, carefully posed, hollow-eyed, and literate. He attracted attention. By the spring of 1892 he had begun to draw in the linear style which would make him famous, though nothing was published at this stage. He would sketch a design in pencil and then work over it in black ink, producing images of the strongest contrast: black, white, and no greys. He seems to have grasped the potential of the new process blocks, which were replacing wood-engravings at this time as a medium for reproducing images alongside letterpress. Process blocks were made, not of wood, but of metal, on to which the image was transferred photographically. Being stronger than woodblocks, they could sustain finer lines without breaking down in the printing press. The thin, isolated black lines which sweep so voluptuously across the white in some of Beardsley's most famous drawings are a tribute to the process block, which no other illustrator of the 1890s exploited quite so tellingly. In May the young man went to Paris and boldly showed his work to Puvis de Chavannes. The president of the Salon du Champ de Mars was impressed, and introduced him to another artist as ‘un jeune artiste anglais qui fait des choses étonnantes’ (Sturgis, 103).

In the autumn the publisher J. M. Dent asked Beardsley to illustrate Malory's Morte d'Arthur in the style of the books beginning to come from William Morris's Kelmscott Press, with their scrolling borders and wood-engraved illustrations by Burne-Jones. The book was a favourite with the Pre-Raphaelites, there were plenty of illustrations, and the pay was good. Beardsley resigned from his job and began to draw, working at first in something like the Kelmscott style. Dent also commissioned him to draw ornaments for a series of eighteenth-century anthologies, to be titled Bon mots. Among the eighty or so calligraphic doodles he produced were pierrots, hermaphrodites, ballet dancers, prostitutes, satyrs, and foetuses with old men's heads and angry eyes. In his imagination, sex was often mingled with sadness and deformity. In his personal life we hardly know what part it played. There are stories of mistresses he may have had, but none of any close or lasting relationship.

Salome

At about the same time, through Vallance, Beardsley's work was chosen as the subject of an article in the first number of The Studio, a new periodical of fine and decorative art. He was beginning to be known, and wrote to his old housemaster at Brighton grammar school: ‘There is quite an excitement in the art world here about my “new method”’ (Letters, 38). In February 1893 Oscar Wilde's play Salome was published in London, and the Pall Mall Budget asked Beardsley for a drawing. He wove an ornate, macabre, and, in places, sickening graphic fantasy around the horrific climax of the play, Salome embracing the severed head of John the Baptist. The Budget rejected it, but in April it appeared in the first number of The Studio. Wilde liked the drawing, and his publishers suggested that Beardsley do an illustrated edition of the play. He was not yet twenty-one, but he had reached the shores of notoriety.

And of respectability. In June 1893 the Beardsleys took a lease on a four-storey house at 114 Cambridge Street, Pimlico, from which you could just see through the trees into Warwick Square. After years of shifting from one set of lodgings to another, they could hold up their heads and entertain their friends, thanks to Aubrey's earnings as an illustrator and a small inheritance. The two connecting rooms on the first floor were turned into a drawing-room-cum-studio, and here the Beardsleys were at home on Thursday afternoons. Ellen sent out the invitations, but Mabel and Aubrey were in reality the hosts. (Vincent Beardsley was no longer in evidence. Aubrey's friends thought he might be dead, or locked in the basement.) Mabel, who had beautiful red hair, greeted the visitors and Aubrey handed round the cakes. Max Beerbohm thought Beardsley was at his best on these occasions, his natural kindliness and good manners shining through the veneer of affectation.

By September Beardsley had completed only half the Morte d'Arthur illustrations and was bored stiff with the Holy Grail. He wanted Salome and wickedness. In the end he completed them with a bad grace, putting more of Beardsley than of Malory into the later ones. His linear style and sensuality show through the pastiche neo-medievalism. But then Beardsley did not think it was his job to illustrate a writer's words. Though he had a literary imagination, and most of his drawings illustrate texts, he usually drew as if artist and writer were independent. He complained that the illustrator trailed servant-like behind the author in modern English magazines. At the turn of 1893–4 Beardsley and an American friend, the writer Henry Harland, proposed a new, avant-garde magazine in which writers and artists would have equal standing. John Lane, who was publishing Salome at the Bodley Head, agreed to publish it as a quarterly, called the Yellow Book, with Harland as editor for literature and Beardsley for art.

In February 1894 the illustrated Salome appeared and created a succès de scandale. (Beardsley perhaps began to feel that that was the only kind of success he needed.) The seventeen illustrations were in his classic, Japanese-influenced style of flat, decorative, asymmetrical images, with intricate detail, large areas of black, and fine lines curving over areas of white. Reviewers acknowledged Beardsley's technical skill but were disturbed, both by the threatening sexuality, rendered with such graphic elegance, and by the fact that many of the drawings were irrelevant to Wilde's text. For the Art Journal the effect was ‘terrible in its weirdness and suggestions of horror and wickedness’ (Art Journal, 14, 1894, 139). Some reviewers thought it was all a bitchy joke, Beardsley parodying Wilde in the spaces of his own text.

The Yellow Book

Two months later the first number of the Yellow Book appeared, with a Beardsley cover and four Beardsley drawings. There was much else in it: writing by Henry James, George Saintbury, and Richard Garnett, pictures by Sir Frederic Leighton, president of the Royal Academy, and Robert Anning Bell—serious, irreproachable names. But Beardsley's drawings were all disturbing in one way or another, and The Times's reviewer, pointing to the cover, wrote of ‘repulsiveness and insolence’ (20 April 1894, 3). The magazine became a talking point because of his work, and the first edition of 5000 copies sold out in five days. This was notoriety. Beardsley had discovered, long before Andy Warhol or Damien Hirst, that there is a kind of art which consists in shocking the public.

In a sense, Beardsley's public persona was as much a work of art as his drawings. He cultivated a dandified appearance before the world, and liked to appear wicked, witty, and decadent like the French. He let his reddish hair fall in a fringe so that he looked half like a boy, and dressed his poor thin body immaculately, as if he expected not to be touched by life—a grey suit, grey gloves, a golden tie, a tasselled cane. Artificiality became him. He worked ferociously hard, but the painter William Rothenstein remembered that ‘His work done, Aubrey loved to get into evening clothes and drive into the town’ (Rothenstein, 186). He could be found with his friends, Rothenstein, the caricaturist Max Beerbohm, and the writers Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symons, in the Domino Room of the Café Royal in Regent Street, or among the prostitutes and their gentlemen friends in the St James's Restaurant in Piccadilly Circus, dipping into low life. With the appearance of Salome and the Yellow Book Beardsley became notorious in a way that his friends were not. He was caricatured in the press and was sung about in music-halls. He almost ranked in the public eye with Oscar Wilde who, though a friend, was older, a hero, and a rival. But notoriety did not change him, perhaps because it was what his so-careful dressing, his shocking drawings, and his mask of wit had been asking for all along.

On 5 April 1895 Wilde was arrested at the Cadogan Hotel in Knightsbridge on twenty charges of gross indecency with young men. As he left the hotel under a police escort, he picked up a book with a yellow cover. The press mistook it for the Yellow Book. Thus Beardsley was caught up in the débâcle of Wilde's trials and disgrace. A crowd threw stones through the windows of the Bodley Head office in Vigo Street. On 8 May a group of contributors asked that Beardsley be dismissed as editor for art. John Lane, then in America, felt pressured to agree. Beardsley was unaware of developments for some days. Yet Wilde had nothing to do with the Yellow Book: Beardsley and Lane had kept him out, fearing that he would sail the ship. And Beardsley was not homosexual, though he enjoyed camp conversation. But, by sacking him, Lane virtually admitted his complicity with Wilde. With the editorship, Beardsley lost his main source of income, and the house at 114 Cambridge Street, which had given him security for barely two years, had to be given up. In June he and Mabel took a short lease on a house at 57 Chester Terrace (now Chester Row), on the Pimlico side of Belgravia.

The Savoy

At this point Beardsley acquired two guardian angels. One, André Raffalovich, was an angel of light: a rich, homosexual, thirty-year-old aesthete who became Beardsley's friend and mentor and helped him with money. The other, Leonard Smithers, was an angel of darkness: a pasty-faced, thirty-four-year-old ex-solicitor who sold old books, prints, and pornography from a shop in Arundel Street, off the Strand. Smithers was setting up as a publisher and proposed to start a rival to the Yellow Book, with Arthur Symons dealing with literature and Beardsley with art. They named it The Savoy. Beardsley set to work eagerly. He wanted more of the dangerous publishing he had just experienced, not less. A streak of self-destructiveness emerged. In October he took rooms in Geneux's private hotel in St James's Place. They were not cheap, and Wilde had used them two years before for assignations. Raffishness at the Café Royal and St James's Restaurant now gave way to dissipation in low dives round Leicester Square and at a supper club called the Thalia, favoured by Smithers.

The Wilde débâcle was not such a disaster that Beardsley could not have survived it. But, coming when it did, it broke the magic of his short career. He could no longer step from one shocking little triumph to the next, outwitting his physical condition and his spiritual unease with dandyism and hard work. It caused an unravelling. He still drew, and the drawings were as new in style and as remarkable as his earlier work. But his life had become a river of dissolution, and the drawings floated on it like light craft.

The first number of The Savoy appeared in January 1896. It was like the Yellow Book in style and content, and the press greeted it accordingly, but with less excitement. After the party to launch it, Smithers and a few friends went back to his flat, where Beardsley had a slight haemorrhage. W. B. Yeats recalled Smithers, sweat pouring from his face, turning the handle of a hurdy-gurdy piano while Beardsley, propped up on a chair in the middle of the room and grey from loss of blood, urged him on, exclaiming ‘The tone is so beautiful’ (Yeats, 329). It lacked only a Roman Catholic priest, blessing it all, for the decadent scene to be complete.

Sex and death

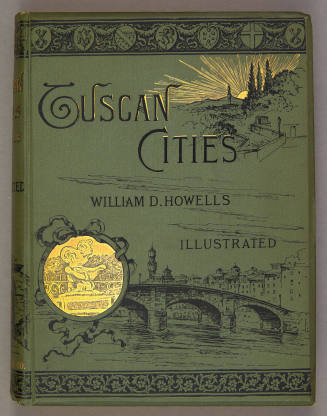

And yet Beardsley could work. He wanted to write as well as draw, and had been working on a version of the Tannhäuserlied. Its story of sex, sin, and forgiveness touched him. He made some drawings for it, but the more he wrote the more pornographic it became, and in the end Smithers could publish it in The Savoy only in unfinished and expurgated form. Late in 1895 Beardsley took up Edmund Gosse's suggestion that he illustrate Pope's The Rape of the Lock, for he had not illustrated a complete book since Salome. For some time he had admired Watteau and the frippery world of French rococo engravers, so Pope appeared dressed very tellingly in that style rather than in Japanese asymmetry and sweeping lines. When the book was published in May 1896 the press were taken with its ladies in billowing lace and its mincing courtiers. Here were parody and excess quite different from the bourgeois-domestic image of the eighteenth century then popular with illustrators; but there was none of the evil they had felt before. Actually, Beardsley was learning to divide his life with skill. While he was illustrating Pope he was also, at Smithers's suggestion, illustrating Lysistrata, Aristophanes' tale of a sex strike among Athenian women, with gross, buttocky Athenians in rococo frills and monstrous, comic penises. Smithers published these privately in 1896.

In February 1896 Beardsley went to Paris with Smithers and a girl from the Thalia. When Smithers went back to London, Beardsley stayed on in Paris, working. Smithers then returned, en route for Brussels. Beardsley took him to the station and then got on the train himself, on an impulse. When he arrived in Brussels he collapsed. He was there for about three months. When he returned to London the doctors looked grave. For much of his adult life Beardsley had been fighting a battle with his body. The dandyism, the wicked drawings, the eager baiting of the British philistine, had all been sand thrown in the face of this enemy. It began to seem less possible.

Beardsley and his mother returned to their old ways of shifting from one address to another, from lodgings to hotels, from hotels to guest houses. (Mabel now had a career in the theatre.) The doctors always said that another place would be better for his health. In June it was Epsom; in August it was Boscombe in Hampshire, for the sea air. In December he suffered a violent haemorrhage near the cliff-top, and a trail of blood followed him and his mother down the hill. He was moved to nearby Bournemouth for the mild climate and the smell of pines. And there, on 31 March 1897, he was received into the Catholic church. Mabel had recently become a Catholic and so had Raffalovich. Now Beardsley needed its certainties. Serious, asexual men in black came to his bedside and ministered to his soul.

In April Beardsley was in Paris; in May in St Germain-en-Laye on the outskirts of Paris; in June in Dieppe; in September in Paris again. It was becoming a way of life. In each place there would be a new hotel, the view, the local priest, old friends coming to visit. He would find somewhere to sit outside in the morning under the trees, charming the other guests and the local children, reading Catholic devotional literature and erotica by turns, writing a little, drawing a little. Then there would be another doctor and another move.

Finally, late in 1897, it was Menton on the French riviera, and the Hotel Cosmopolitan. Beardsley's mother made the room look nice with his Mantegna prints on the wall and photographs on the bookshelf: Mabel, Raffalovich, Wagner. He was drawing ornaments for Ben Jonson's Volpone and working excitedly in half-tone instead of line. But as he got weaker he could not draw any more. Early in March he wrote a short letter to Smithers:

Jesus is our Lord and Judge.

Dear Friend,

I implore you to destroy all copies of Lysistrata and bad drawings ... By all that is holy, all obscene drawings.

Aubrey Beardsley

In my death agony.

(Letters, 439)

It was his last letter. Smithers, of course, paid no attention to it, knowing what the drawings would soon be worth. Aubrey Beardsley died on 16 March 1898, aged twenty-five, and was buried in the public cemetery at Menton.

Reputation

Beardsley's reputation since his death has had little of the scandalous excitement it had during his life. For many years it was maintained in a quiet, cultish way, chiefly by collectors and bibliophiles. Dent and John Lane went on republishing his work. There were studies and memoirs, often coloured by literary nostalgia for the avant-garde culture of the 1890s. Beardsley influenced artists and designers in Europe and America, and there were important exhibitions of his work in Budapest (1907), in Chicago and Buffalo (1911–12), and at the Tate Gallery in London (1923). In the United States the painter and art historian A. E. Gallatin formed the pre-eminent collection of Beardsley's work, which he gave to Princeton University Library in 1948. (The other two major collections are at the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.) In England a book dealer and collector called R. A. Walker did the same for Beardsley memorabilia. His A Beardsley Miscellany (1949) underpins parts of all subsequent biography.

Then, for a moment in the 1960s, Beardsley became part of popular culture, in art posters and advertisements, in Haight-Ashbury and swinging London, on T-shirts and record sleeves (the Beatles' Revolver, 1966). Both his graphic style and his indecencies were of the time. The year 1966 also saw a major exhibition of Beardsley's work at the Victoria and Albert Museum, which introduced him to a larger, less cultish audience. And since then there has been an important shift in his reputation, which is now in the hands of academics as well as of collectors and bibliophiles. But he is not necessarily better or more widely understood. There has been no outstanding work of scholarship or criticism, no substantial and accessible reassessment. Instead, Beardsley has been parcelled out among different intellectual allegiances—biography, connoisseurship, cultural theory, bibliography, race and gender studies, reception studies. He has been fragmented. No one would have said so during his short and painful life, but now, a hundred years later, it is actually hard to see who Aubrey Beardsley was.

Alan Crawford

Sources M. Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley: a biography (1998) · B. Reade, Beardsley (1967) · The letters of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. H. Maas, J. L. Duncan, and W. G. Good (1970) · S. Calloway, Aubrey Beardsley (1998) · R. A. Walker, ed., A Beardsley miscellany (1949) · M. S. Lasner, A selective checklist of the published work of Aubrey Beardsley (1995) · N. A. Salerno, ‘An annotated secondary bibliography’, in R. Langenfeld, Reconsidering Aubrey Beardsley (1989), 267–493 · W. Rothenstein, Men and memories: recollections of William Rothenstein, new edn, 2 vols. (1934) · W. B. Yeats, Autobiographies (1956) · K. Keserü, ‘Art contacts between Great Britain and Hungary at the turn of the century’, Hungarian Studies, 6/2 (1990), 141–54 · L. Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley and Victorian sexual politics (1990) · C. Snodgrass, Aubrey Beardsley: dandy of the grotesque (1995) · L. Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme and the perversion of the Victorian ideal (1997) · J. H. Desmarais, The Beardsley industry: the critical reception in England and France (1998) · b. cert. · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1898) · will, Probate Department of the Principal Registry of the Family Division, London

Archives Harvard U., Houghton L., writings and drawings · Princeton University Library, drawings, posters, photographs, MSS, sketchbook, and corresp. · Ransom HRC, corresp. with André Raffalovich · U. Reading L., corresp. and papers of and relating to him, incl. letters to John Gray · Yale U., Beinecke L., recollections and related papers :: Bodl. Oxf., corresp. with John Lane and André Raffalovich · E. Sussex RO, archives of Brighton grammar school · Harvard U., Houghton L., corresp. with William Rothenstein and Henry James · Hunt. L., corresp. with Leonard Smithers · U. Cal., Los Angeles, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, corresp. with Florence Farr and Maurice Baring

Likenesses J. Russell & Sons, photograph, c.1890, NPG · D. S. MacColl, drawing, 1893, Princeton University Library, Gallatin collection · F. H. Evans, two photographs, 1893–4, NPG [see illus.] · M. Beerbohm, caricature, c.1894, V&A · F. Hollyer, photograph, c.1894, V&A · W. Sickert, oils, 1894, Tate collection · M. Beerbohm, caricature, c.1895, AM Oxf. · J. E. Blanche, oils, 1895, NPG · Grip [A. Brice], caricature, Indian ink and wash, 1896, V&A; repro. in The Sketch (13 May 1896) · W. Rothenstein, lithograph, 1897, NPG · photograph, 1897, NPG · A. Beardsley, self-portrait, pen and ink, BM · M. Beerbohm, caricature, repro. in The Savoy, 2 · W. Sickert, drawing, NPG

Wealth at death £1015 17s. 10d.: probate, 13 May 1898, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–15

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Alan Crawford, ‘Beardsley, Aubrey Vincent (1872–1898)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/1821, accessed 13 Nov 2015]

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

London, 1809 - 1885, Vichy

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1936, New York