Image Not Available

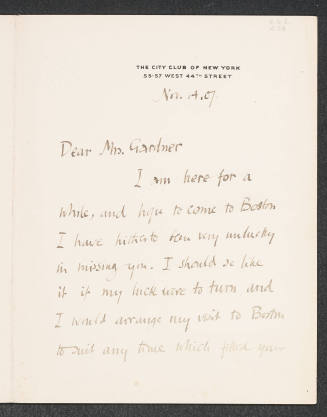

for Leonard Sidney Woolf

Leonard Sidney Woolf

London, 1880 - 1969, Rodmell, East Sussex

S. P. Rosenbaum, ‘Woolf, Leonard Sidney (1880–1969)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/37019, accessed 30 Aug 2017]

Woolf, Leonard Sidney (1880–1969), author and publisher, was born on 25 November 1880 in Kensington, London, the third of ten children of Sidney Woolf QC (1844–1892) and his wife, Marie de Jongh (1848–1939). He was brought up in Reform Judaism, became an atheist in his teens, and remained sceptical about the religious temperament. Some of his earlier writing depicts antisemitism, but Woolf maintained that it had no influence on his life. Woolf was eleven when his father died, leaving his family in financial difficulties. Fears of economic and social instability underlay Woolf's political convictions. His mother risked her small capital to educate her children, who then supported her. Woolf attended St Paul's School for five years as a scholar. He went to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1899 on scholarships for five years, obtaining a first class in part one of the classical tripos (1902) but only a second in part two (1903). At Trinity, Woolf became friends with Saxon Sydney-Turner, Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, and Thoby Stephen (son of Sir Leslie, brother of Virginia and Vanessa). Out of these friendships the Bloomsbury group developed.

Woolf's formative education at Cambridge took place largely through the Apostles, to which he was elected—the first Jew—in 1902. G. E. Moore was the dominant influence there, and to him Woolf owed his commitment to rationality, clarity, and common sense; Moore's concern with states of mind and his basic distinction in Principia ethica (1903) between instrumental and intrinsic value was incorporated into Woolf's political theory. Through the Apostles Woolf also came to know John Maynard Keynes, Roger Fry, Desmond MacCarthy, and E. M. Forster—all of whom became associated with the Bloomsbury group—as well as Bertrand Russell and Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, who influenced Woolf's political writings.

In 1904, partly because of his family's financial needs, Woolf joined the colonial civil service in Ceylon rather than becoming a schoolmaster or lawyer. He served for seven years, at Jaffna, Kandy, and finally, Hambantota where, as the youngest assistant government agent in the service, he administered 100,000 Sinhalese in a district of 1000 miles. There he continued what he later called his anti-imperialist education. Striving to improve the lives of the villagers with an efficiency that was at times ruthless, he became increasingly ambivalent about his government's mismanagement of jungle agriculture, the absurdity of one civilization imposing itself on another, and the hypocrisy of the British failure to prepare its colony for self-government. Returning on leave to England in 1911, Woolf began The Village in the Jungle (1913), a novel that movingly reflected these concerns. He became involved again in London with his Cambridge friends and relatives who now made up the Bloomsbury group: Virginia Stephen, her sister and brother-in-law, Vanessa and Clive Bell, Vanessa's future partner, Duncan Grant, Strachey, Fry, Keynes, Forster, and the MacCarthys. Woolf's growing disillusionment with imperialism was one reason for his resignation from the civil service in 1912, but a more important motive was that he had fallen in love with Virginia Stephen (1882–1941) [see Woolf, (Adeline) Virginia].

With their marriage on 10 August 1912, Virginia took Leonard's family name and made it that of the most famous woman writer of her time. For literary history, Leonard became, in effect, Mr Virginia Woolf. He had recognized her genius before their marriage, but not the extent of her mental instability. For nearly thirty years one of Leonard's chief occupations was caring for Virginia. Without his vigilant love, her books would never have been written; he was her first reader, her editor, and her publisher. Though not a sexually active marriage, theirs was one of profound and enduring affection. In 1915 the Woolfs moved to Richmond for ten years, then returned to Bloomsbury; weekends and longer periods were spent in Sussex where in 1919 they bought Monk's House, a cottage in Rodmell, near Vanessa's family at Charleston. There with Virginia, Leonard wrote, gardened, bowled, cared for his dogs, and worked as parish clerk. The Woolfs were bombed out of Bloomsbury in 1940. After Virginia's suicide in 1941 Leonard continued to live alone at Monk's House and in London; he watched over Virginia's reputation, publishing five volumes of her uncollected essays, and editing a selection of her diaries. A late loving relationship of Leonard's with the artist Marjorie Tulip (Trekkie) Parsons (1902–1996) is revealed in their published letters.

Leonard Woolf's education as a socialist began with his return from Ceylon. After his autobiographical second novel, The Wise Virgins (1914), which satirized Bloomsbury and offended his family, Woolf turned to journalism for a livelihood. He became interested in the Women's Co-operative Guild through friendship with Margaret Llewelyn Davies, and joined the Fabian Society under the tutelage of Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Woolf wrote two books on consumer co-operative socialism, maintaining in them that economics should be organized according to the needs of consumers and that control of production is a means toward a civilized life rather than an end in itself, as both capitalists and Marxists thought. He had become, he wrote later, ‘a socialist of a rather peculiar sort’ (Beginning Again, 105).

With the First World War, Woolf's critiques of imperialism and capitalism coalesced into internationalism. An inherited tremor of his hands kept him from having to decide whether he was a conscientious objector. In 1916 he wrote two Fabian reports on international government, arguing that it could make war unlikely through the resolution of disputes, and showing how far international laws and organizations already existed without compromising state sovereignty. Woolf's reports became part of the basis for the League of Nations and then the United Nations.

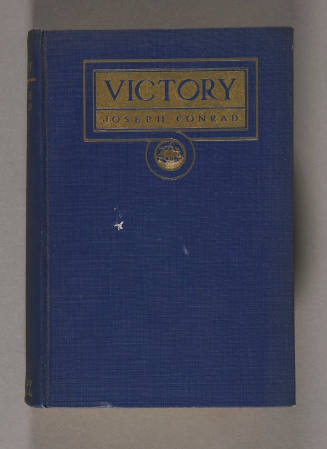

During the First World War Woolf also became involved in editing the first of a series of periodicals; he eventually contributed towards editing The Nation, the Political Quarterly (which he co-founded in 1931), and the New Statesman. Even more important was the Hogarth Press, which Leonard and Virginia started in 1917. With no printing or publishing experience and no capital, the Woolfs created a remarkable enterprise that expressed their Bloomsbury values. Its initial purpose was to publish modernist writing that the Woolfs liked and that other publishers did not. They began by printing two of their own stories and then works by various writers including Katherine Mansfield and T. S. Eliot. They went on to publish work by many others including Forster, Fry, Keynes, Russell, Vita Sackville-West, Christopher Isherwood, Freud (the standard translation of his writings), and of course Virginia Woolf herself. The Hogarth Press was never a full-time activity for the Woolfs, but something they initially did as recreation from their writing. As the press grew and prospered it became a burden, and in 1938 Virginia sold her half-interest to John Lehmann, who remained Leonard's partner until their disagreements led Woolf to sell Lehmann's share to Chatto and Windus in 1946.

After the First World War, Woolf's anti-imperialism, socialism, and internationalism found expression in a number of books and pamphlets, the most important being Empire and Commerce in Africa (1920), which analysed the economic imperialism of African colonization. Woolf began to develop here the theory of political history that he expressed more fully in later books. The logic of history, he claimed, was to be found only in the beliefs, desires, and ideals of individuals' states of mind that made up what he called ‘communal psychology’.

From 1919 to 1945 Woolf served as secretary to the Labour Party's advisory committees on international and imperial questions. He was literary editor of the Nation and Athenaeum, under Keynes's chairmanship, from 1923 to 1930, when the Woolfs' rising income enabled him to resign and write After the Deluge: a Study of Communal Psychology. The first volume (1931) surveyed the growth of democratic communal psychology in the eighteenth century; the second (1939) concentrated on 1830 to 1832. Woolf interrupted this work to write three shorter books in the 1930s on totalitarianism. In them he again advocated the need for socialist co-operation and international government, and he warned of the impending destruction of his civilization's values, which for Woolf were freedom, democracy, equality, justice, liberty, tolerance, and the love of beauty, art, and intellect. Woolf's insistence on these liberal (and Bloomsbury) values alienated socialist colleagues not yet disillusioned by Stalinism. The last volume of After the Deluge, retitled Principia politica (1953), became something of a political autobiography. Two more volumes were planned, but Woolf abandoned them after reviews criticizing his knowledge, methodology, and organization. He turned instead to direct autobiography and wrote the five volumes on which his reputation as a writer now mainly rests. Sowing (1960), Growing (1961), Beginning Again (1964), Downhill All the Way (1967), and The Journey not the Arrival Matters (1969) provide the most reliable description of the development and character of the Bloomsbury group as well as an indispensable account of Virginia Woolf's life by the person who knew her best.

Leonard Woolf's own personality is revealed in his autobiographies with remarkable detachment and integrity; a fatalistic strain in them sometimes masks the considerable charm, dry humour, and deep feelings of the man. The high value he gave rationality renders his political analyses simplistic at times, yet he knew how little most people were guided by reason. Woolf's capacity for unremitting, efficient work made him hard on subordinates; he once calculated that his had done between 150,000 and 200,000 hours of wholly useless work. Futile as his political writing and committee work may have appeared to him, he was nevertheless right about the wrongs of imperialism and capitalism, the need for international organization, and the evils of fascist and communist totalitarianism. Leonard Woolf suffered a stroke and died at Monk's House on 14 August 1969. Following cremation, his ashes were buried there.

Sources

L. Woolf, Sowing (1960); Growing (1961); Beginning again (1964); Downhill all the way (1967); The journey not the arrival matters (1969); published as Q. Bell, introduction, An autobiography (1980) · L. Woolf, Letters, ed. F. Spotts (1989) · L. Luedeking and M. Edmonds, Leonard Woolf: a bibliography (1992) · A. O. Bell and A. McNeillie, eds., Virginia Woolf: diary, 5 vols. (1977–84) · The letters of Virginia Woolf, ed. N. Nicolson, 6 vols. (1975–80) · Q. Bell, Virginia Woolf: a biography, 2 vols. (1972) · L. Woolf and T. Parsons, Love letters, 1941–1968, ed. J. Adamson (2000) · D. Wilson, Leonard Woolf: a political biography (1978) · G. Spater and I. Parsons, A marriage of true minds: an intimate portrait of Leonard and Virginia Woolf (1977) · J. H. Willis, Leonard and Virginia Woolf as publishers: the Hogarth Press, 1917–1941 (1992) · J. H. Woolmer, A checklist of the Hogarth Press, 1917–1946, 2nd edn (1986) · S. P. Rosenbaum, Victorian Bloomsbury (1987) · S. P. Rosenbaum, Edwardian Bloomsbury (1994) · S. P. Rosenbaum, Georgian Bloomsbury [forthcoming] · S. S. Meyerowitz, Leonard Woolf (1982) · H. Lee, Virginia Woolf (1996) · M. Cole, ‘Woolf, Leonard Sidney’, DLB, vol. 5 · N. Rosenfeld, Outsiders together: Virginia and Leonard Woolf (2000) · DNB · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1970)

Archives

NYPL, Berg collection, corresp. and literary papers · U. Sussex, corresp., family papers, and literary MSS · U. Texas :: BL, letters to John Lehmann, Add. MS 56234 · Hunt. L., letters to Saxon Sydney-Turner · King's AC Cam., letters to Julian Bell · King's AC Cam., letters to John Maynard Keynes and Lady Keynes · King's AC Cam., letters to G. H. W. Rylands · King's Cam., Charleston papers · U. Durham L., letters to William Plomer · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Norah Smallwood · U. Reading, Hogarth Press archives · U. Sussex, Monks House Papers FILM

BBC interview conducted by Malcolm Muggeridge, recorded March 1967 SOUND

BL NSA, ‘Leonard Woolf’, BBC Radio 3, 17 Feb 1970, P503R · BL NSA, performance recordings

Likenesses

V. Bell, double portrait, oils, 1912 (with Adrian Stephen), U. Hull · H. Lamb, oils, 1912, priv. coll. · V. Bell, oils, c.1938, NPG · G. Freund, colour print, 1939, NPG · V. Bell, oils, 1940, NPG [see illus.] · T. Parsons, oils, 1945, Monks House, Sussex · C. Hewer, bronze bust, 1968, NPG · photographs, repro. in Woolf, Autobiography · photographs, repro. in Spater and Parsons, Marriage of true minds · photographs, NPG

Wealth at death

£157,732: administration, 1970 · £157,732—further grant: 1971

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

London, 1830 - 1894, London

Berdychiv, Ukraine, 1857 - 1924, Bishopsbourne, England

Rugby, England, 1887 - 1915, Skyros, Greece

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Philadelphia, 1829 - 1914, Philadelphia

Saxmundham, England, 1843 - 1926, Sissinghurst, England