Silas Weir Mitchell

Philadelphia, 1829 - 1914, Philadelphia

He was son of a physician, John Kearsley Mitchell (1798–1858), and was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

He studied at the University of Pennsylvania in that city, and received the degree of M.D. at Jefferson Medical College in 1850. During the Civil War he had charge of nervous injuries and maladies at Turners Lane Hospital, Philadelphia, and at the close of the war became a specialist in neurology. In this field Mitchell's name became prominently associated with his introduction of the rest cure, subsequently taken up by the medical world, for nervous diseases, particularly neurasthenia and hysteria.[1] The treatment consisted primarily in isolation, confinement to bed, dieting, electrotherapy and massage; and was popularly know as 'Dr Diet and Dr Quiet'.[1] His medical texts include Injuries of Nerves and Their Consequences (1872) and Fat and Blood (1877). Mitchell's disease (erythromelalgia) is named after him. He also coined the term phantom limb during his study of an amputee.[2]

Silas Weir Mitchell discovered and treated causalgia (today known as CRPS/RSD), a condition most often encountered by hand surgeons. He is considered the father of neurology as well as an early pioneer in scientific medicine. He was also a psychiatrist, toxicologist, author, poet, and a celebrity in America and Europe. His many skills and interests led his contemporaries to consider him a genius on par with Benjamin Franklin. His contributions to medicine and particularly hand surgery continue to resonate today.

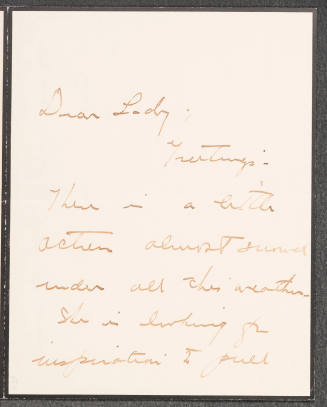

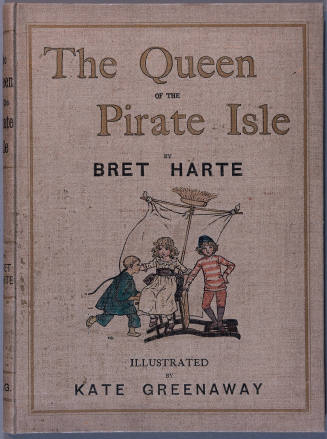

In 1866 he wrote a short story, combining physiological and psychological problems, entitled "The Case of George Dedlow", in the Atlantic Monthly.[3] From that point onward, Mitchell, as a writer, divided his attention between professional and literary pursuits. In the former field, he produced monographs on rattlesnake venom, on intellectual hygiene, on injuries to the nerves, on neurasthenia, on nervous diseases of women, on the effects of gunshot wounds upon the nervous system, and on the relations between nurse, physician, and patient; while in the latter, he wrote juvenile stories, several volumes of respectable verse, and prose fiction of varying merit, which nonetheless gave him a leading place among the American authors of the close of the 19th century. His historical novels, Hugh Wynne, Free Quaker (1897), The Adventures of François (1898) and The Red City (1909), take high rank in this branch of fiction.

He was Charlotte Perkins Gilman's doctor and his use of a rest cure on her provided the idea for "The Yellow Wallpaper", a short story in which the narrator is driven insane by her rest cure.

His treatment was also used on Virginia Woolf, who wrote a savage satire of it: "you invoke proportion; order rest in bed; rest in solitude; silence and rest; rest without friends, without books, without messages; six months rest; until a man who went in weighing seven stone six comes out weighing twelve".[4]

Influence on Freud[edit]

Sigmund Freud reviewed Mitchell's book on The Treatment of Certain Forms of Neurasthenia and Hysteria in 1887;[5] and used electrotherapy in his work into the 1890s.[6]

Freud also adopted Mitchell's use of physical relaxation as an adjunct to therapy, which arguably resulted eventually in the employment of the psychoanalytic couch.[7]

Honors and recognition[edit]

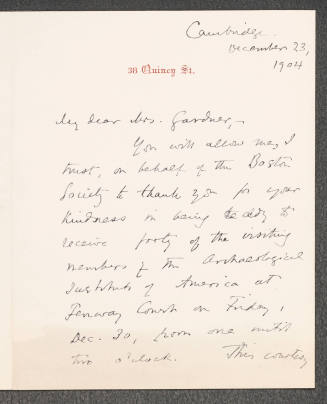

Mitchell's eminence in science and letters was recognized by honorary degrees conferred upon him by several universities at home and abroad and by membership, honorary or active, in many American and foreign learned societies. In 1887 he was president of the Association of American Physicians and in 1908–09 president of the American Neurological Association.

The American Academy of Neurology award for young researchers, the S. Weir Mitchell Award, is named for him.[8]

Crotalus mitchellii, the speckled rattlesnake, was named after Mitchell.[9]

Terms[edit]

Weir Mitchell skin – a red, glossy, perspiring skin seen in cases of incomplete irritative lesion of a nerve.

Weir Mitchell treatment – a method of treating neurasthenia, hysteria, etc., by absolute rest in bed, frequent and abundant feeding, and the systematic use of massage and electricity.

Mitchell's disease – erythromelalgia.

Dorland's Medical Dictionary (1938)

Selected publications[edit]

Mitchell, S. Weir and Edward T. Reichert. 1886. Researches upon the Venoms of Poisonous Serpents. Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Number 647. The Smithsonian Institution. Washington, District of Columbia. 179 pp.

"Circumstance" by S. Weir Mitchell, MD. LL.D. Harvard and Edinburgh. Copyright 1901 by The Century Co. Published 1902 by The Century Co.

Rest in the Treatment of Nervous Disease by S. Weir Mitchell

Art patron[edit]

He was a friend and patron of the artist Thomas Eakins, and owned the painting Whistling for Plover.[10] The Philadelphia Chippendale chairs seen in several Eakins paintings – such as William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of Schuylkill River (1877) and the bas-relief Knitting (1883) – were borrowed from Mitchell. Following Eakins's 1886 forced resignation from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Mitchell may have recommended the artist's trip to the Badlands of South Dakota.

The artist John Singer Sargent painted two portraits of Mitchell: one is in the collection of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia; the other, commissioned by the Mutual Assurance Company of Philadelphia in 1902, was recently sold (see External Links, below).

The sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens modeled an 1884 bronze portrait plaque of Mitchell.[11] Mitchell commissioned Saint-Gaudens to create a monument to his deceased daughter Maria: The Angel of Purity, a white marble version of the sculptor's Amor Caritas. Originally installed in Saint Stephen's Church, Philadelphia, it is now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

References[edit]

^ Jump up to: a b Ellenberger, Henri F. (August 2008). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. Basic Books. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7867-2480-2.

Jump up ^ Woodhouse, Annie (2005). "Phantom limb sensation". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 32 (1-2): 132–134. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04142.x. ISSN 0305-1870.

Jump up ^ Mitchell, Silas Weir (July 1866). "The Case of George Dedlow". Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

Jump up ^ Lee, Hermione (1996). Virginia Woolf. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 194. ISBN 9780701165079.

Jump up ^ Jones, Ernest (1964). The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud. p. 210.

Jump up ^ Gay, Peter (2006). Freud: A Life for Our Time. W. W. Norton. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-393-32861-5.

Jump up ^ Ellenberger, p. 518.

Jump up ^ American Academy of Neurology: S. Weir Mitchell award

Jump up ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (26 July 2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. JHU Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5.

Jump up ^ Reason, Akela (2010). Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-8122-4198-3.

Jump up ^ Silas Weir Mitchell by Saint-Gaudens from Smithsonian Institution.

Further reading[edit]

Nancy Cervetti, S. Weir Mitchell, 1829-1914: Philadelphia's Literary Physician. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.

E. P. Oberholtzer, "Personal Memories of Weir Mitchell," in the Bookman, vol. 39 (1914).

A. Proust and G. Ballet, The Treatment of Neurasthenia. 1902.

B. R. Tucker, S. Weir Mitchell. Boston, 1914.

Talcott Williams, "Dr. S. Weir Mitchell" in the Century Magazine, vol. 57 (1898).

Talcott Williams, in several articles in the Book News Monthly, vol. 26 (1907).

A Catalogue of the Scientific and Literary Work of S. Weir Mitchell. Philadelphia, 1894. (Wikipedia)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Paris, 1861 - 1930, New York

Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1860 - 1938, Saunderstown, Rhode Island

Urumiah, Persia, 1852 - 1908, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Surbiton, Surrey, 1863 - 1920, London

active New York, 1896-1961

New York, 1879 - 1971, La Jolla, California

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London