Daniel Chester French

Exeter, New Hampshire, 1850 - 1931, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

At a young age French demonstrated artistic qualities that were encouraged by his stepmother and by family friends including Abigail May Alcott, an artist. She had studied art in Paris and was able to help him learn basic sculpture techniques. He spent one year at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, where he learned drawing. French is usually described as being "largely self-taught," but he had learned from many teachers by observing them in their studios. Early influences were William Morris Hunt on drawing and color, John Quincy Adams Ward on sculpture, and William Rimmer on anatomy.

French's first big commission came with the help of a family friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson, a resident of Concord. That town and Lexington commissioned a sculpture to celebrate the one-hundredth anniversary of the American Revolution's first battle. French's studio was in Boston at the time, and he produced a model slightly over two feet tall that was accepted without dissent. The statue became the Minute Man, with a musket in one hand and the other hand resting on a plow. This image of the citizen-farmer-soldier became famous and was used to sell U.S. war bonds during World War I. The Minute Man was unveiled one day before French's twenty-fifth birthday, on 19 April 1875, before a crowd of 10,000. President Ulysses S. Grant, Speaker of the House James G. Blaine, and several cabinet members were there. James Russell Lowell and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were in the crowd, and Emerson read a poem, the lines of which were cut into the granite pedestal of the statue. French, however, was not present at the unveiling, since he had moved in 1874 to Florence, Italy. French lived there in the home of the sculptor Preston Powers for two years, working alongside Powers and under the guidance of Thomas Ball.

On his return to America French proceeded to establish a studio in Washington, D.C., on the site of the current Library of Congress. Here he turned his attention to sculptural groups on new public buildings. His first three commissions were for the St. Louis Custom House (1877), the Court House in Philadelphia (1883), and the Boston Post Office (1885), all of which were in marble. Around the same time he also executed the seated bronze statue of John Harvard, placed in the Harvard Yard.

Completed in 1888, French's standing statue of General Lewis Cass in marble stands in National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, Washington, D.C., representing the state of Michigan. This statue is French's only work in the hall, and according to critics, it is one of the best. Lorado Taft in History of American Sculpture said it had "an individuality, an equipoise, and a technical perfection undreamed of by the earlier generation of American sculptors."

About this time French went to Paris, where he worked with Augustus Saint-Gaudens and others, including the sculptor Edward Clark Potter. He enrolled for Antonin Mercié's sculpture class, and his modeling grew more crisp and definite. On his return to the U.S., French used the style of the École des Beaux-Arts, but he emerged as an "American" sculptor as the influences of European sculpture (e.g. romantic interpretations of nature and classic echoes) weakened.

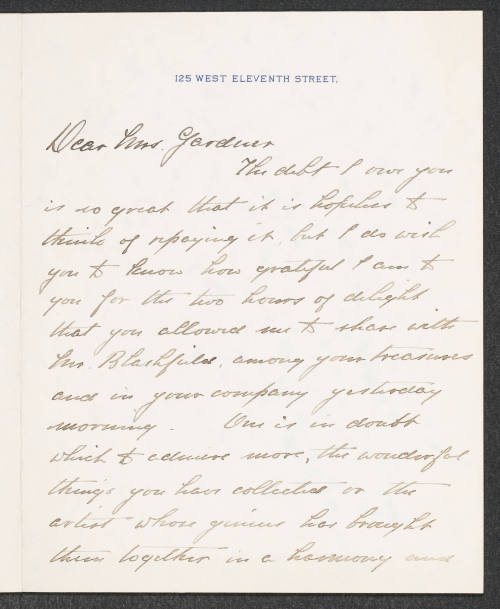

French postponed marriage until age thirty-eight, then even postponed his wedding so that he could finish his statue of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet (at Gallaudet College, Washington, D.C.). His bride was his cousin Mary Adams French; they had one daughter and settled in lower Manhattan. French maintained a studio in New York City for the remaining forty-two years of his life.

The friendship of French and Saint-Gaudens paid dividends when the latter was chosen director of sculpture at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Saint-Gaudens selected his friend French to design a massive statue, which was seventy-five feet tall when complete. A twenty-foot model of this statue, The Republic, was later permanently installed in the city of Chicago.

Death Staying the Hand of the Young Sculptor was fashioned by French as a tribute to Martin Milmore, a younger, less well-known sculptor who died a premature death in 1883. The bronze original was erected at Milmore's grave in Roxbury, Massachusetts, at Forest Hills Cemetery in 1893, and a marble replica is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Among the many equestrian statues French designed with the help of Edward Clark Potter are General Grant in Philadelphia (1899); Washington (1900), a gift from the women of America to France placed in the Place d'Iéna in Paris; and General Joseph Hooker in Boston (1903). The breadth of his work is seen in the bronze doors of the Boston Public Library, the fountain in Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C., and various war memorials.

For all this diversity, French is best remembered for his portrayal of Abraham Lincoln in the massive seated statue in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. At the dedication on Memorial Day 1922, President Warren G. Harding said that the Lincoln statue "will be a national shrine forever." Designing the memorial itself was French's friend Henry Bacon, a noted architect. French is quoted as saying that Bacon was created for the sole purpose of making the memorial.

The colossal statue required approximately twenty blocks of Georgia marble, cut and reassembled on site so skillfully that the seams are almost invisible. The seated Lincoln is about eighteen feet high, a dimension French arrived at by painstakingly constructing models and testing them until he was satisfied with the proportions relative to the interior space of Bacon's temple. (The pedestal adds another eleven feet to the piece.) Lord Charnwood, a Lincoln biographer whose work French studied during his preparation, saw a photograph of the completed statue and proclaimed it the finest Lincoln he had ever seen, citing specifically its stability, repose, and natural majesty. He went on to say that the only one approaching it was in the state house in Lincoln, Nebraska. A friend of French's wrote to Lord Charnwood to inform him that French had also created that one.

Examples of French's sculpture are now found in more than thirty-five cities, both in the U.S. and abroad. His work in Washington, D.C., alone requires a map of the city for its presentation. Although he lived there but a few years (1876-1878), French had a fondness for the American capital, demonstrated by his work on the national Commission of Fine Arts. He and others had sought such a group since the mid-1890s, but it was not until 1910 that congress approved the legislation. The duty of the commission was "to advise upon the location of statues, fountains, and monuments in the public squares, streets, and parks in the District of Columbia." This commission brought artistic input and continuity to the congressional decision-making process, which had previously appointed a different committee to advise on each project under consideration. French served as a member of the commission from 1910 to 1915, the last three years as chairman.

About 1896 French and his wife bought a farm in the town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, to serve as a summer home and studio. Bacon began construction of a summer studio for French in 1898, and in 1900 he also designed the large (seventeen main rooms) residence French built on the property. French named the estate "Chesterwood" after Chester, New Hampshire, where he had spent some childhood summers with his grandparents. It is said that his affection for the town caused him to adopt its name as his middle name. About the estate, he said "I spend six months of the year up there. That is heaven. New York is--well, New York."

The gardens, modeled after English and Italian gardens, were French's pride and joy. He spent much time designing them and working in them. Chesterwood was used by the family for many years, and in 1969 French's daughter Margaret gave the 120-acre estate to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It is now open to the public, and his studio remains as it was when he was active. The doors are some twenty-two feet high, and one can see the railroad track French used to wheel models in and out of the sunlight so that he could oversee the effect of natural light on his work. The largest collection of French's work is there in the Berkshires at Chesterwood.

French was a founder of the American Academy at Rome in 1905 as part of his effort to encourage young sculptors. He supported the fledgling school with labor and money during its early years, in part undoubtedly because of his own training in Italy. He belonged to many artistic organizations, including the National Sculpture Society and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, of which he was a trustee from 1904 until his death. He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

French's awards were numerous, including medals of honor from the Paris Exposition, 1900; from the New York Architectural League in 1912; from the Panama-Pacific exposition at San Francisco in 1915 and from the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1918. France honored him twice: he became a chevalier of the Legion of Honor in 1910, and ten years later he became one of only nineteen foreign associate members of the fine arts class of the French Academy.

When French died at Chesterwood, funeral services were held in his studio at Chesterwood. He is remembered for using his European training and influences in developing American sculpture and in particular for his seated Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial. This monument, seen by millions each year, conveys the power and dignity of its subject in a way demonstrated by few, if any, other pieces.

Bibliography

French's papers are in the Library of Congress. Biographies of French written by family members are Journey into Fame: the Life of Daniel Chester French (1947), by French's daughter Margaret French Cresson (a sculptress herself), and Memories of a Sculptor's Wife (1928), by his wife Mary French, published three years before his death. Cresson's work has a particularly complete list of French's work and an extensive bibliography. Michael Richman has written two works about French: an exhibit catalog, Daniel Chester French, an American Sculptor/Washington, D.C. (1976 and 1983 editions), and "The Early Career of Daniel Chester French, 1869-1891" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Delaware, 1974). Works that discuss French while dealing with specific statuary include Roland Wells Robbins, The Story of the Minute Man (1945); New York (State) Sheridan Monument Commission, Unveiling of the Equestrian Statue of General Philip H. Sheridan, Capitol Park, Albany, New York, October 7, 1916 (1916); Georgia Historical Society, A History of the Erection and Dedication of the Monument to Gen'l James Edward Oglethorpe, Savannah, Ga. (1911); Robert Henry Myers, Beneficence; the Statue on the Campus of Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana (1972); and Lorado Taft, History of American Sculpture (1903).

Philip H. Viles, Jr.

Back to the top

Citation:

Philip H. Viles, Jr.. "French, Daniel Chester";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00301.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:48:58 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Paris, 1861 - 1930, New York

Dublin, 1848 - 1907, Cornish, New Hampshire

Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, 1863 - 1938, New York, New York

Salem, Massachusetts, 1819 - 1895, Vallombrosa, Italy

London, 1845 - 1916, Tunbridge Wells, Kent

Vilnius, 1843 - 1902

Chester, England, 1846 - 1886, Saint Augustine, Florida

Watertown, Massachusetts, 1830 - 1908, Watertown, Massachusetts