Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer

New York, 1851 - 1934, New York

Van Rensselaer, Mariana Griswold (25 Feb. 1851-20 Jan. 1934), art critic, was born in New York City, the daughter of George Catlin Griswold, a merchant, and Lydia Alley. The offspring of two wealthy, patrician parents, she was educated at home before being taken in 1868 to Dresden, Germany, where she completed her education. While there, in 1873, she married Schuyler Van Rensselaer, a mining engineer from the New Jersey branch of this great patroon family. The couple soon returned to the United States, where they lived in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and at diverse mining sites, until his death from a lung disease in 1884. They had one child. After Schuyler's death, Van Rensselaer lived in New York City for the remainder of her life.

Van Rensselaer's first art criticism appeared in the first volume of the Boston-based American Architect and Building News in May 1876. Her last of more than seventy articles in that journal appeared in 1887. Her reviews in this journal of the annual exhibitions of the National Academy of Design and the Society of American Artists remain the most insightful contemporary record of the process by which young artists trained in Europe replaced an older nativist school at the forefront of American art. In these reviews, and in those she wrote as art critic for the New York World during the early 1880s and as principal art critic for the Independent between 1886 and 1889, she introduced American readers to new stylistic concepts, such as creative spontaneity, and new aesthetic ideals, including poetic expressiveness. An enduring relationship with the editors of Century Magazine, especially her good friend and mentor Richard Watson Gilder, began with an 1880 essay in its predecessor Scribner's Monthly and ended only in 1916. Through her nine-article series on "Recent Architecture in America," which appeared in Century between 1884 and 1886, Van Rensselaer emerged as one of America's first professional architectural critics.

Buoyed by the reception of her architectural criticism, Van Rensselaer wrote between 1886 and 1888 the study that many consider the foundation of modern architectural history, Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works (1888; repr. 1967). H. H. Richardson had died suddenly in 1886 at the height of his influence as creator of the Richardsonian Romanesque. Van Rensselaer's book was the first in-depth study of an American architect, and it not only became--and remains--the foundation for later Richardson scholarship but introduced what soon became the standard framework for studying an architect's life and work. She judiciously probed all aspects of Richardson's childhood, education, working practices, and major commissions; the book brought together all available documentation of his life and career and photographs, drawings, and plans, when possible, of all of his buildings.

Influenced by her long-standing friendship with landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Van Rensselaer soon turned her attention to gardening. In more than fifty essays on landscape design that she wrote between 1888 and 1897 for Garden and Forest, published by Charles Sprague Sargent of the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard, she helped Olmsted elevate landscape design to the rank of a fine art equivalent with architecture, sculpture, and painting. As she had done with architecture, she helped establish landscape architecture as an honored profession. Her interest in gardening lessened after she revised her favorite articles for publication as Art Out-of-Doors: Hints on Good Taste in Gardening (1893).

Van Rensselaer did not relinquish her interest in the other arts. In her book Six Portraits (1889) she published the first extended study of Winslow Homer. Having earlier been critical of Homer's "crudity," she became the first of countless writers to apotheosize at length Homer's Americanness.

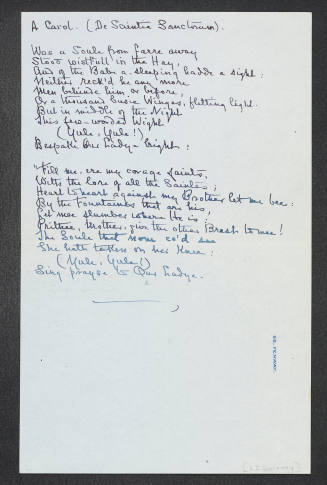

Like many writers of her era Van Rensselaer had begun by publishing poetry, starting with "Prayers," in Harper's Monthly for April 1876, and after 1900 poetry would represent the bulk of her serial publications. A collection of previously published poems, titled simply Poems, was published by Macmillan in 1910. Her poetry was highly sentimental. The critic for the New York Times Book Review saw in her poems "a philosophy untinged of doubt or melancholy . . . carrying through its cultivated thought, a message of sweetness and light" (29 Jan. 1911, p. 38). A second volume of her poems, Many Children, appeared in 1921.

Van Rensselaer won professional and scholarly accolades then unusual for a woman. She was granted an honorary doctorate by Columbia University in 1910 in recognition of her two-volume History of the City of New York in the Seventeenth Century (1909), in which she tried to give New Yorkers a new pride in their history. In 1923 she received the gold medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Although resolved to be perceived as a professional critic rather than a woman writer, Van Rensselaer remained the product of her genteel conditioning. After first subordinating herself to her spouse's career, she later published her important books as Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer. From 1894 through 1920 she was an outspoken opponent of woman suffrage, stressing the danger of letting ignorant, immigrant, and lower-class women vote. Yet at the same time, she was a strong proponent of public education and helping ambitious poor girls. Following the death of her son in 1894, she did volunteer work at the Neighborhood Guild on Delancey Street, where she taught neighborhood girls Egyptian archaeology. She served before World War I as president of the Public Education Association of New York; during the war she led the American Fund for the French Wounded.

Van Rensselaer maintained a home on West Tenth Street long after New York's nouveau riche had moved uptown. Beginning in the 1890s she entertained weekly at tea her many friends in literature, publishing, and the visual arts, especially Gilder and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who sculpted the famous relief of her in the Metropolitan Museum; Gilder spent his last illness and died in her house. Van Rensselaer died in New York City.

Van Rensselaer is unknown today beyond circles of historians. One reason for her neglect is that like so many patrician critics of her era, she brought a hauteur to criticism that results in an absolutism and a preachiness that makes her unappealing to modern sensibilities. In the same way, the Victorian gentility that led her to publish her important books as Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer and then speak out vigorously against woman suffrage reduces her attractiveness to students of women's history. Nevertheless, she played a seminal role in the foundation of architectural history and was America's most articulate and widely published art critic.

Bibliography

Van Rensselaer's papers are scattered in archives listed in Dinnerstein (below). Van Rensselaer published many articles and essays on art and landscape gardening in the short-lived American Art Review, the Atlantic Monthly, Lippincott's, Harper's Monthly, and the Chautauquan. See also her English Cathedrals (1892; repr. frequently), essays that originally appeared in Century; American Etchers (1886), which reprints an essay that appeared in Century; and her introduction to The Book of American Figure Painters (1886). Van Rensselaer has been the subject of two doctoral dissertations: Cynthia Doering Kinnard, "The Life and Works of Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer, American Art Critic" (Johns Hopkins Univ., 1977), and Lois Dinnerstein, "Opulence and Ocular Delight, Splendor and Squalor: Critical Writings in Art and Architecture by Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer" (CUNY, 1979). The best summary of her life and career is Kinnard's "Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer (1851-1934): America's First Professional Woman Art Critic," in Women as Interpreters of the Visual Arts, 1820-1979, ed. Claire Richter Sherman (1981). Her contribution to architectural biography is discussed in Lisa Koenigsberg, " 'Lifewriting': First American Biographers of Architects and Their Works," in The Architectural Historian in America, ed. Elisabeth Blair MacDougall (1990). A modern article on her is Dinnerstein, "Thomas Eakins' 'Crucifixion' as perceived by Mariana Griswold van Rensselaer," Arts 53 (May 1979): 140-45. Far removed from the art world, Van Rensselaer provided glimpses of the various mining towns where she and her husband resided in In the Heart of the Alleghenies, Historical and Descriptive (1885). Obituaries are in the New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune, both 21 Jan. 1934.

Saul E. Zalesch

Back to the top

Citation:

Saul E. Zalesch. "Van Rensselaer, Mariana Griswold";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00889.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:44:10 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Albany, New York, 1868 - 1959, Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Philadelphia, 1855 - 1942, Gloucester, Massachusetts

Boston, 1861 - 1920, Chipping Campden, England

Hyde Park, Massachusetts, 1869 - 1934, New York