Image Not Available

for Plato

Plato

Aigina, Greece, 427 BCE - 346 BCE, Athens

Plato, (born 428/427 bce, Athens, Greece—died 348/347, Athens), ancient Greek philosopher, student of Socrates (c. 470–399 bce), teacher of Aristotle (384–322 bce), and founder of the Academy, best known as the author of philosophical works of unparalleled influence.

Building on the demonstration by Socrates that those regarded as experts in ethical matters did not have the understanding necessary for a good human life, Plato introduced the idea that their mistakes were due to their not engaging properly with a class of entities he called forms, chief examples of which were Justice, Beauty, and Equality. Whereas other thinkers—and Plato himself in certain passages—used the term without any precise technical force, Plato in the course of his career came to devote specialized attention to these entities. As he conceived them, they were accessible not to the senses but to the mind alone, and they were the most important constituents of reality, underlying the existence of the sensible world and giving it what intelligibility it has. In metaphysics Plato envisioned a systematic, rational treatment of the forms and their interrelations, starting with the most fundamental among them (the Good, or the One); in ethics and moral psychology he developed the view that the good life requires not just a certain kind of knowledge (as Socrates had suggested) but also habituation to healthy emotional responses and therefore harmony between the three parts of the soul (according to Plato, reason, spirit, and appetite). His works also contain discussions in aesthetics, political philosophy, theology, cosmology, epistemology, and the philosophy of language. His school fostered research not just in philosophy narrowly conceived but in a wide range of endeavours that today would be called mathematical or scientific.

Life

The son of Ariston (his father) and Perictione (his mother), Plato was born in the year after the death of the great Athenian statesman Pericles. His brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus are portrayed as interlocutors in Plato’s masterpiece the Republic, and his half brother Antiphon figures in the Parmenides. Plato’s family was aristocratic and distinguished: his father’s side claimed descent from the god Poseidon, and his mother’s side was related to the lawgiver Solon (c. 630–560 bce). Less creditably, his mother’s close relatives Critias and Charmides were among the Thirty Tyrants who seized power in Athens and ruled briefly until the restoration of democracy in 403.

Plato as a young man was a member of the circle around Socrates. Since the latter wrote nothing, what is known of his characteristic activity of engaging his fellow citizens (and the occasional itinerant celebrity) in conversation derives wholly from the writings of others, most notably Plato himself. The works of Plato commonly referred to as “Socratic” represent the sort of thing the historical Socrates was doing. He would challenge men who supposedly had expertise about some facet of human excellence to give accounts of these matters—variously of courage, piety, and so on, or at times of the whole of “virtue”—and they typically failed to maintain their position. Resentment against Socrates grew, leading ultimately to his trial and execution on charges of impiety and corrupting the youth in 399. Plato was profoundly affected by both the life and the death of Socrates. The activity of the older man provided the starting point of Plato’s philosophizing. Moreover, if Plato’s Seventh Letter is to be believed (its authorship is disputed), the treatment of Socrates by both the oligarchy and the democracy made Plato wary of entering public life, as someone of his background would normally have done.

After the death of Socrates, Plato may have traveled extensively in Greece, Italy, and Egypt, though on such particulars the evidence is uncertain. The followers of Pythagoras (c. 580–c. 500 bce) seem to have influenced his philosophical program (they are criticized in the Phaedo and the Republic but receive respectful mention in the Philebus). It is thought that his three trips to Syracuse in Sicily (many of the Letters concern these, though their authenticity is controversial) led to a deep personal attachment to Dion (408–354 bce), brother-in-law of Dionysius the Elder (430–367 bce), the tyrant of Syracuse. Plato, at Dion’s urging, apparently undertook to put into practice the ideal of the “philosopher-king” (described in the Republic) by educating Dionysius the Younger; the project was not a success, and in the ensuing instability Dion was murdered.

Plato’s Academy, founded in the 380s, was the ultimate ancestor of the modern university (hence the English term academic); an influential centre of research and learning, it attracted many men of outstanding ability. The great mathematicians Theaetetus (417–369 bce) and Eudoxus of Cnidus (c. 395–c. 342 bce) were associated with it. Although Plato was not a research mathematician, he was aware of the results of those who were, and he made use of them in his own work. For 20 years Aristotle was also a member of the Academy. He started his own school, the Lyceum, only after Plato’s death, when he was passed over as Plato’s successor at the Academy, probably because of his connections to the court of Macedonia.

Because Aristotle often discusses issues by contrasting his views with those of his teacher, it is easy to be impressed by the ways in which they diverge. Thus, whereas for Plato the crown of ethics is the good in general, or Goodness itself (the Good), for Aristotle it is the good for human beings; and whereas for Plato the genus to which a thing belongs possesses a greater reality than the thing itself, for Aristotle the opposite is true. Plato’s emphasis on the ideal, and Aristotle’s on the worldly, informs Raphael’s depiction of the two philosophers in the School of Athens (1508–11). But if one considers the two philosophers not just in relation to each other but in the context of the whole of Western philosophy, it is clear how much Aristotle’s program is continuous with that of his teacher. (Indeed, the painting may be said to represent this continuity by showing the two men conversing amicably.) In any case, the Academy did not impose a dogmatic orthodoxy and in fact seems to have fostered a spirit of independent inquiry; at a later time it took on a skeptical orientation.

Plato once delivered a public lecture, “"On the Good,"” in which he mystified his audience by announcing, “the Good is one.” He better gauged his readers in his dialogues, many of which are accessible, entertaining, and inviting. Although Plato is well known for his negative remarks about much great literature, in the Symposium he depicts literature and philosophy as the offspring of lovers, who gain a more lasting posterity than do parents of mortal children. His own literary and philosophical gifts ensure that something of Plato will live on for as long as readers engage with his works.

Dating, editing, translation

Plato’s works are traditionally arranged in a manner deriving from Thrasyllus of Alexandria (flourished 1st century ce): 36 works (counting the Letters as one) are divided into nine groups of four. But the ordering of Thrasyllus makes no sense for a reader today. Unfortunately, the order of composition of Plato’s works cannot be known. Conjecture regarding chronology has been based on two kinds of consideration: perceived development in content and “stylometry,” or the study of special features of prose style, now executed with the aid of computers. By combining the two kinds of consideration, scholars have arrived at a widely used rough grouping of works, labeled with the traditional designations of early, middle, and late dialogues. These groups can also be thought of as the Socratic works (based on the activities of the historical Socrates), the literary masterpieces, and the technical studies (see below Works individually described).

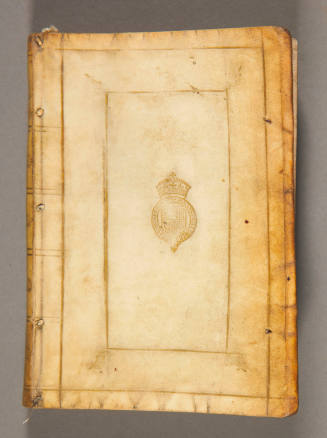

Phaedo by Plato; portion of manuscript, 3rd century bce.

Phaedo by Plato; portion of manuscript, 3rd century bce.

Heritage-Images/Imagestate

Each of Plato’s dialogues has been transmitted substantially as he left it. However, it is important to be aware of the causal chain that connects modern readers to Greek authors of Plato’s time. To survive until the era of printing, an ancient author’s words had to be copied by hand, and the copies had to be copied, and so on over the course of centuries—by which time the original would have long perished. The copying process inevitably resulted in some corruption, which is often shown by disagreement between rival manuscript traditions.

Even if some Platonic “urtext” had survived, however, it would not be anything like what is published in a modern edition of Plato’s works. Writing in Plato’s time did not employ word divisions and punctuation or the present-day distinction between capital and lowercase letters. These features represent the contributions of scholars of many generations and countries, as does the ongoing attempt to correct for corruption. (Important variant readings and suggestions are commonly printed at the bottom of each page of text, forming the apparatus criticus.) In the great majority of cases only one decision is possible, but there are instances—some of crucial importance—where several courses can be adopted and where the resulting readings have widely differing import. Thus, the preparation of an edition of Plato’s works involves an enormous interpretive component. The work of the translator imports another layer of similar judgments. Some Greek sentences admit of several fundamentally different grammatical construals with widely differing senses, and many ancient Greek words have no neat English equivalents.

A notable artifact of the work of translators and scholars is a device of selective capitalization sometimes employed in English. To mark the objects of Plato’s special interest, the forms, some follow a convention in which one capitalizes the term Form (or Idea) as well as the names of particular forms, such as Justice, the Good, and so on. Others have employed a variant of this convention in which capitalization is used to indicate a special way in which Plato is supposed to have thought of the forms during a certain period (i.e., as “separate” from sensible particulars, the nature of this separation then being the subject of interpretative controversy). Still others do not use capital letters for any such purpose. Readers will do best to keep in mind that such devices are in any case only suggestions.

In recent centuries there have been some changes in the purpose and style of English translations of ancient philosophy. The great Plato translation by Benjamin Jowett (1817–93), for example, was not intended as a tool of scholarship; anyone who would undertake such a study already knew ancient Greek. Instead, it made Plato’s corpus generally accessible in English prose of considerable merit. At the other extreme was a type of translation that aimed to be useful to serious students and professional philosophers who did not know Greek; its goal was to indicate as clearly as possible the philosophical potentialities of the text, however much readability suffered in consequence. Exemplars of this style, which was much in vogue in the second half of the 20th century, are the series published by the Clarendon Press and also, in a different tradition, the translations undertaken by followers of Leo Strauss (1899–1973). Except in a few cases, however, the gains envisioned by this notion of fidelity proved to be elusive.

Despite, but also because of, the many factors that mediate the contemporary reader’s access to Plato’s works, many dialogues are conveyed quite well in translation. This is particularly true of the short, Socratic dialogues. In the case of works that are large-scale literary masterpieces, such as the Phaedrus, a translation of course cannot match the artistry of the original. Finally, because translators of difficult technical studies such as the Parmenides and the Sophist must make basic interpretive decisions in order to render any English at all, reading their work is very far from reading Plato. In the case of these dialogues, familiarity with commentaries and other secondary literature and a knowledge of ancient Greek are highly desirable.

Dialogue form

Glimpsed darkly even through translation’s glass, Plato is a great literary artist. Yet he also made notoriously negative remarks about the value of writing. Similarly, although he believed that at least one of the purposes—if not the main purpose—of philosophy is to enable one to live a good life, by composing dialogues rather than treatises or hortatory letters he omitted to tell his readers directly any useful truths to live by.

One way of resolving these apparent tensions is to reflect on Plato’s conception of philosophy. An important aspect of this conception, one that has been shared by many philosophers since Plato’s time, is that philosophy aims not so much at discovering facts or establishing dogmas as at achieving wisdom or understanding (the Greek term philosophia means “love of wisdom”). This wisdom or understanding is an extremely hard-won possession; it is no exaggeration to say that it is the result of a lifetime’s effort, if it is achieved at all. Moreover, it is a possession that each person must win for himself. The writing or conversation of others may aid philosophical progress but cannot guarantee it. Contact with a living person, however, has certain advantages over an encounter with a piece of writing. As Plato pointed out, writing is limited by its fixity: it cannot modify itself to suit the individual reader or add anything new in response to queries. So it is only natural that Plato had limited expectations about what written works could achieve. On the other hand, he clearly did not believe that writing has no philosophical value. Written works still serve a purpose, as ways of interacting with inhabitants of times and places beyond the author’s own and as a medium in which ideas can be explored and tested.

Dialogue form suits a philosopher of Plato’s type. His use of dramatic elements, including humour, draws the reader in. Plato is unmatched in his ability to re-create the experience of conversation. The dialogues contain, in addition to Socrates and other authority figures, huge numbers of additional characters, some of whom act as representatives of certain classes of reader (as Glaucon may be a representative of talented and politically ambitious youth). These characters function not only to carry forward particular lines of thought but also to inspire readers to do the same—to join imaginatively in the discussion by constructing arguments and objections of their own. Spurring readers to philosophical activity is the primary purpose of the dialogues.

Because Plato himself never appears in any of these works and because many of them end with the interlocutors in aporia, or at a loss, some scholars have concluded that Plato was not recommending any particular views or even that he believed that there was nothing to choose between the views he presented. But the circumstance that he never says anything in his own person is also compatible with the more common impression that some of the suggestions he so compellingly puts forward are his own. Further, there are cases where one may suppose that Plato sets an exercise that the reader must work through so as to gain the benefit of philosophical progress that cannot be obtained merely by being told “the answer.” Although attributing views to Plato on the basis of such reconstructions must be conjectural, it is clear that the process of engaging in such activity so as to arrive at adequate views is one that he wanted his readers to pursue.

Happiness and virtue

The characteristic question of ancient ethics is “How can I be happy?” and the basic answer to it is “by means of virtue.” But in the relevant sense of the word, happiness—the conventional English translation of the ancient Greek eudaimonia—is not a matter of occurrent mood or affective state. Rather, as in a slightly archaic English usage, it is a matter of having things go well. Being happy in this sense is living a life of what some scholars call “human flourishing.” Thus, the question “How can I be happy?” is equivalent to “How can I live a good life?”

Whereas the notion of happiness in Greek philosophy applies at most to living things, that of arete—“virtue” or “excellence”—applies much more widely. Anything that has a characteristic use, function, or activity has a virtue or excellence, which is whatever disposition enables things of that kind to perform well. The excellence of a race horse is whatever enables it to run well; the excellence of a knife is whatever enables it to cut well; and the excellence of an eye is whatever enables it to see well. Human virtue, accordingly, is whatever enables human beings to live good lives. Thus the notions of happiness and virtue are linked.

In the case of a bodily organ such as the eye, it is fairly clear wherein good functioning consists. But it is far from obvious what a good life consists of, and so it is difficult to say what virtue, the condition that makes it possible, might be. Traditional Greek conceptions of the good life included the life of prosperity and the life of social position, in which case virtue would be the possession of wealth or nobility (and perhaps physical beauty). The overwhelming tendency of ancient philosophy, however, was to conceive of the good life as something that is the achievement of an individual and that, once won, is hard to take away.

Already by Plato’s time a conventional set of virtues had come to be recognized by the larger culture; they included courage, justice, piety, modesty or temperance, and wisdom. Socrates and Plato undertook to discover what these virtues really amount to. A truly satisfactory account of any virtue would identify what it is, show how possessing it enables one to live well, and indicate how it is best acquired.

In Plato’s representation of the activity of the historical Socrates, the interlocutors are examined in a search for definitions of the virtues. It is important to understand, however, that the definition sought for is not lexical, merely specifying what a speaker of the language would understand the term to mean as a matter of linguistic competence. Rather, the definition is one that gives an account of the real nature of the thing named by the term; accordingly, it is sometimes called a “real” definition. The real definition of water, for example, is H2O, though speakers in most historical eras did not know this.

In the encounters Plato portrays, the interlocutors typically offer an example of the virtue they are asked to define (not the right kind of answer) or give a general account (the right kind of answer) that fails to accord with their intuitions on related matters. Socrates tends to suggest that virtue is not a matter of outward behaviour but is or involves a special kind of knowledge (knowledge of good and evil or knowledge of the use of other things).

The Protagoras addresses the question of whether the various commonly recognized virtues are different or really one. Proceeding from the interlocutor’s assertion that the many have nothing to offer as their notion of the good besides pleasure, Socrates develops a picture of the agent according to which the great art necessary for a good human life is measuring and calculation; knowledge of the magnitudes of future pleasures and pains is all that is needed. If pleasure is the only object of desire, it seems unintelligible what, besides simple miscalculation, could cause anyone to behave badly. Thus the whole of virtue would consist of a certain kind of wisdom. The idea that knowledge is all that one needs for a good life, and that there is no aspect of character that is not reducible to cognition (and so no moral or emotional failure that is not a cognitive failure), is the characteristically Socratic position.

In the Republic, however, Plato develops a view of happiness and virtue that departs from that of Socrates. According to Plato, there are three parts of the soul, each with its own object of desire. Reason desires truth and the good of the whole individual, spirit is preoccupied with honour and competitive values, and appetite has the traditional low tastes for food, drink, and sex. Because the soul is complex, erroneous calculation is not the only way it can go wrong. The three parts can pull in different directions, and the low element, in a soul in which it is overdeveloped, can win out. Correspondingly, the good condition of the soul involves more than just cognitive excellence. In the terms of the Republic, the healthy or just soul has psychic harmony—the condition in which each of the three parts does its job properly. Thus, reason understands the Good in general and desires the actual good of the individual, and the other two parts of the soul desire what it is good for them to desire, so that spirit and appetite are activated by things that are healthy and proper.

Although the dialogue starts from the question “Why should I be just?,” Socrates proposes that this inquiry can be advanced by examining justice “writ large” in an ideal city. Thus, the political discussion is undertaken to aid the ethical one. One early hint of the existence of the three parts of the soul in the individual is the existence of three classes in the well-functioning state: rulers, guardians, and producers. The wise state is the one in which the rulers understand the good; the courageous state is that in which the guardians can retain in the heat of battle the judgments handed down by the rulers about what is to be feared; the temperate state is that in which all citizens agree about who is to rule; and the just state is that in which each of the three classes does its own work properly. Thus, for the city to be fully virtuous, each citizen must contribute appropriately.

Justice as conceived in the Republic is so comprehensive that a person who possessed it would also possess all the other virtues, thereby achieving “the health of that whereby we live [the soul].” Yet, lest it be thought that habituation and correct instruction in human affairs alone can lead to this condition, one must keep in view that the Republic also develops the famous doctrine according to which reason cannot properly understand the human good or anything else without grasping the form of the Good itself. Thus the original inquiry, whose starting point was a motivation each individual is presumed to have (to learn how to live well), leads to a highly ambitious educational program. Starting with exposure only to salutary stories, poetry, and music from childhood and continuing with supervised habituation to good action and years of training in a series of mathematical disciplines, this program—and so virtue—would be complete only in the person who was able to grasp the first principle, the Good, and to proceed on that basis to secure accounts of the other realities. There are hints in the Republic, as well as in the tradition concerning Plato’s lecture “"On the Good"” and in several of the more technical dialogues that this first principle is identical with Unity, or the One.

Dialectic

Plato uses the term dialectic throughout his works to refer to whatever method he happens to be recommending as the vehicle of philosophy. The term, from dialegesthai, meaning to converse or talk through, gives insight into his core conception of the project. Yet it is also evident that he stresses different aspects of the conversational method in different dialogues.

The form of dialectic featured in the Socratic works became the basis of subsequent practice in the Academy—where it was taught by Aristotle—and in the teachings of the Skeptics during the Hellenistic Age. While the conversation in a Socratic dialogue unfolds naturally, it features a process by which even someone who lacks knowledge of a given subject (as Socrates in these works claims to do) may test the understanding of a putative expert. The testing consists of a series of questions posed in connection with a position the interlocutor is trying to uphold. The method presupposes that one cannot have knowledge of any fact in isolation; what is known must be embedded in a larger explanatory structure. Thus, in order to know if a certain act is pious, one must know what piety is. This requirement licenses the questioner to ask the respondent about issues suitably related to his original claim. If, in the course of this process, a contradiction emerges, the supposed expert is revealed not to command knowledge after all: if he did, his grasp of the truth would have enabled him to avoid contradiction. While both Socrates and the Skeptics hoped to find the truth (a skeptikos is after all a “seeker”), the method all too often reveals only the inadequacy of the respondent. Since he has fallen into contradiction, it follows that he is not an expert, but this does not automatically reveal what the truth is.

By the time of the composition of the Republic, Plato’s focus had shifted to developing positive views, and thus “dialectic” was now thought of not as a technique of testing but as a means of “saying of each thing what it is.” The Republic stresses that true dialectic is performed by thinking solely of the abstract and nonsensible realm of forms; it requires that reason secure an unhypothetical first principle (the Good) and then derive other results in light of it. Since this part of the dialogue is merely a programmatic sketch, however, no actual examples of the activity are provided, and indeed some readers have wondered whether it is really possible.

In the later dialogue Parmenides, dialectic is introduced as an exercise that the young Socrates must undertake if he is to understand the forms properly. The exercise, which Parmenides demonstrates in the second part of the work, is extremely laborious: a single instance involves the construction of eight sections of argument; the demonstration then takes up some three-quarters of the dialogue. The exercise challenges the reader to make a distinction associated with a sophisticated development of the theory of Platonic forms (see below The theory of forms). Even after a general understanding has been achieved, repeating the exercise with different subjects allows one to grasp each subject’s role in the world.

This understanding of dialectic gives a central place to specifying each subject’s account in terms of genus and differentiae (and so, relatedly, to mapping its position in a genus-species tree). The Phaedrus calls the dialectician the person who can specify these relations—and thereby “carve reality at the joints.” Continuity among all the kinds of dialectic in Plato comes from the fact that the genus-species divisions of the late works are a way of providing the accounts that dialectic sought in all the previous works.

The theory of forms

Plato is both famous and infamous for his theory of forms. Just what the theory is, and whether it was ever viable, are matters of extreme controversy. To readers who approach Plato in English, the relationship between forms and sensible particulars, called in translation “participation,” seems purposely mysterious. Moreover, the claim that the sensible realm is not fully real, and that it contrasts in this respect with the “pure being” of the forms, is perplexing. A satisfactory interpretation of the theory must rely on both historical knowledge and philosophical imagination.

Linguistic and philosophical background

The terms that Plato uses to refer to forms, idea and eidos, ultimately derive from the verb eidô, “to look.” Thus, an idea or eidos would be the look a thing presents, as when one speaks of a vase as having a lovely form. (Because the mentalistic connotation of idea in English is misleading—the Parmenides shows that forms cannot be ideas in a mind—this translation has fallen from favour.) Both terms can also be used in a more general sense to refer to any feature that two or more things have in common or to a kind of thing based on that feature. The English word form is similar. The sentence “The pottery comes in two forms” can be glossed as meaning either that the pottery is made in two shapes or that there are two kinds of pottery. When Plato wants to contrast genus with species, he tends to use the terms genos and eidos, translated as “genus” and “species,” respectively. Although it is appropriate in the context to translate these as “genus” and “species,” respectively, it is important not to lose sight of the continuity provided by the word eidos: even in these passages Plato is referring to the same kind of entities as always, the forms.

Another linguistic consideration that should be taken into account is the ambiguity of ancient Greek terms of the sort that would be rendered into unidiomatic English as “the dark” or “the beautiful.” Such terms may refer to a particular individual that exhibits the feature in question, as when “the beautiful [one]” is used to refer to Achilles, but they may also refer to the features themselves, as when “the beautiful” is used to refer to something Achilles has. “The beautiful” in the latter usage may then be thought of as something general that all beautiful particulars have in common. In Plato’s time, unambiguously abstract terms—corresponding to the English words “darkness” and “beauty”—came to be used as a way of avoiding the ambiguity inherent in the original terminology. Plato uses both kinds of terms.

By Plato’s time there was also important philosophical precedent for using terms such as “the dark” and “the beautiful” to refer to metaphysically fundamental entities. Anaxagoras (c. 500–c. 428 bce), the great pre-Socratic natural scientist, posited a long list of fundamental stuffs, holding that what are ordinarily understood as individuals are actually composites made up of shares or portions of these stuffs. The properties of sensible composites depend on which of their ingredients are predominant. Change, generation, and destruction in sensible particulars are conceived in terms of shifting combinations of portions of fundamental stuffs, which themselves are eternal and unchanging and accessible to the mind but not to the senses.

For Anaxagoras, having a share of something is straightforward: a particular composite possesses as a physical ingredient a material portion of the fundamental stuff in question. For example, a thing is observably hot because it possesses a sufficiently large portion of “the hot,” which is thought of as the totality of heat in the world. The hot is itself hot, and this is why portions of it account for the warmth of composites. (In general, the fundamental stuffs posited by Anaxagoras themselves possessed the qualities they were supposed to account for in sensible particulars.) These portions are qualitatively identical to each other and to portions of the hot that are lost by whatever becomes less warm; they can move around the cosmos, being transferred from one composite to another, as heat may move from hot bathwater to Hector as it warms him up.

Plato’s theory can be seen as a successor to that of Anaxagoras. Like Anaxagoras, Plato posits fundamental entities that are eternal and unchanging and accessible to the mind but not to the senses. And, as in Anaxagoras’s theory, in Plato’s theory sensible particulars display a given feature because they have a portion of the underlying thing itself. The Greek term used by both authors, metechei, is traditionally rendered as “participates in” in translations of Plato but as “has a portion

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Urumiah, Persia, 1852 - 1908, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England