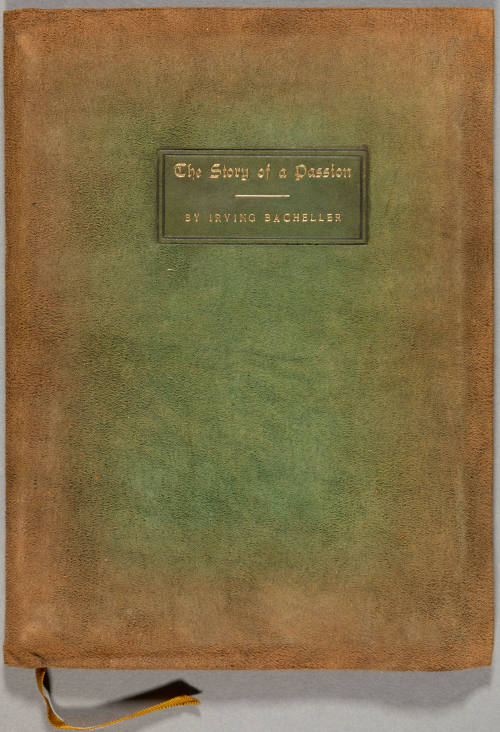

The Roycroft Shop

active East Aurora, New York, 1895 - 1915

Hubbard left school in his sixteenth year and became a door-to-door salesman for his cousin, Justus Weller, a nephew of Dr. Silas, and operator of a soap business with partner John Larkin. Within three years Hubbard was so successful a salesman that he had hired sales teams of his own to canvass the local farms while he concentrated on the shopkeepers of his territory. He was personable, good looking, and a good storyteller. He personified the commercial traveler in his dress, but, unlike his fellow drummers who sat around hotel lobbies and saloons, Hubbard sought out the local lecture halls and book stores and began to absorb the Midwest populist philosophy. In 1875 the Weller-Larkin partnership broke up, and Hubbard chose to work at the reorganized Larkin Company in Buffalo, New York. In 1881 he married Bertha C. Crawford, who soon gave birth to their first child. In 1884 the family moved from Buffalo to the rural, horse-raising suburb of East Aurora, where Hubbard could indulge his love for horses. He also began to be involved in the local book circles that came out of the Chautauqua movement in western New York and started to submit short pieces to the weekly newspaper.

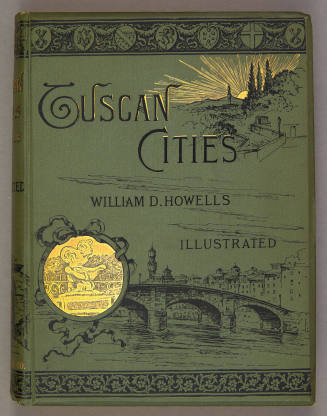

In 1890 Hubbard started writing seriously. His first book, The Man: A Story of Today (1891), was written under the name Aspasia Hobbs and was published by J. S. Ogilvie as part of their Sunnydale Series. It was awful, though it contained hints of the changes in Hubbard. The author(ess) expounds on many topics, including the basic goodness of women, but not wives. This woman/wife dichotomy signals the partition in Hubbard's mind between his wife Bertha and Alice Moore, one of his literary circle acquaintances. In 1892 Hubbard sold his share of and resigned from the Larkin Company and enrolled in Harvard University as a special student. He failed as a student, but while in the Boston area he established a relationship with the Arena publishing house, which published his second book, One Day: A Tale of the Prairies (1893), and was exposed to the new small publishing movement and the new, small monthly magazines.

Hubbard was still living in Boston when a situation that had started in East Aurora came to a head. Alice Moore moved to Boston and soon was carrying Hubbard's child. To gain time before facing the consequences of this liaison, Hubbard journeyed to England. Here one of the self-generated Hubbard myths has its foundation. Hubbard always claimed that he visited with William Morris and that Morris explained the operation of the Kelmscott Press, encouraging him to return and start the American Kelmscott with Hubbard as the American William Morris. In fact, when Hubbard visited Kelmscott, Morris was gravely ill, and Hubbard got the standard tour. He never met Morris, and what he really took from Kelmscott was the sense of Morris's great stature and the realization that there was money in producing fine books.

The year 1894 was the turning point in Hubbard's life. In that year he fathered two daughters: Katherine, by his wife Bertha; and Miriam, by Alice Moore. Child support payments were arranged, and Miriam was sent to Alice's relatives in Buffalo while she left for Denver, Colorado. With this sticky situation temporarily resolved, Hubbard used the journal of his English trip to write the first Little Journey biographical booklet and made the rounds of publishers without success. A local acquaintance from his advertising days, Harry P. Taber, suggested that Hubbard have the piece printed in a way that would show it in a finished, printed form. Hubbard made the rounds again with the printed samples, and this time Putnam and Sons accepted the series and contracted for one Little Journey booklet a month. Hubbard had also started writing essays for Taber's The Philistine magazine, and when Taber decided to produce a book through his Roycroft Printing Shop, he invited Hubbard to participate. The first book, The Song of Songs, with an introductory essay by Hubbard, was published, and a second title, The Journal of Koheleth, again with an introductory essay by Hubbard, followed. Neither book had much literary or aesthetic merit, but Hubbard had found a new role as a writer and as a publisher. Producing a few issues of The Philistine and Hubbard's two books had exhausted Taber's financial resources, and in 1895 he sold the rights to the Roycroft Printing Shop, The Philistine, and his interest in White and Waggoner's printing shop to Hubbard for one thousand dollars. The first two titles and most of the early numbers of The Philistine came along as unsold stock. The books were crudely done, but The Philistine had attracted some good material from contemporary writers.

Hubbard quickly turned the little literary magazine into his own platform and brought well-trained craftsmen into the Roycroft Printing Shop. Hubbard was not a creative writer in the literary sense, but he was an advertising genius and used his copywriting and promotion skills to turn the early, unsalable The Philistine press run of 2,000 in 1895 into a press run of 110,000 at its peak in 1902. The rapid early increase in circulation was mostly the result of an untitled essay Hubbard included in the March 1899 Philistine. It spoke of doing your job without question and about loyalty and the rewards of work well done. It was about the message to Garcia carried by Lt. Rowan during the Spanish-American War. Orders for this issue of The Philistine poured in and Hubbard gave permission to George H. Daniels of the New York Central Railroad to republish the essay as one of the railroad's promotional pieces. This little essay, titled A Message to Garcia, brought Hubbard his audience of independent farmers, small businessmen, and company executives, and it is probably the only work written by Hubbard that has remained in print. When Hubbard had new presses ready he took over the printing of the essay as a booklet, and it gave him the financial as well as the ideological base for expansion.

Within five years the little printing shop grew into the multibuilding Roycroft campus, and the Roycroft enterprise became the largest and most complex exponent of the American arts and crafts movement. It had shops for printing and binding and for furniture, metal, and leather work; it also established training schools for the local youth in drawing, watercolor, and bookbinding. Hubbard did not follow the philosophy of the arts and crafts movement that the "heart" (the humanistic spirit) and hand of the craftsman had to be the tools of creation and not subservient to the machine and mass production. Indeed, he mechanized as much of the entire Roycroft enterprise as was possible. Although he constantly proclaimed the arts and crafts philosophy of hand crafting in his promotional advertising for the books produced, the printing shop was among the largest and most mechanized on the East Coast.

Despite or perhaps because of the fact it was mechanized, the printing shop attracted some of the best creative and craft talent. Hubbard allowed free experimentation and never questioned the cost throughout the shops. Designers and craftsmen could work out ideas and, if unsuccessful, just start over. There were never deadlines for the books or prohibitions on design motifs. Hubbard's only prohibition was idleness, and his only requirement for employment was acceptance of Elbert Hubbard as the guiding patron, "the Fra." The material produced by the print shop and bindery from 1896 to 1912 was always of high quality. By 1912 most of the best designers, such as Dard Hunter and the binder Louis Kinder, had left to establish their own enterprises.

On the literary side, a young writer like Stephen Crane gladly sent material to his friend Hubbard, and established authors such as George Bernard Shaw gave permission to reprint pieces. Crane had offered Hubbard The Black Riders (1895), which Hubbard rejected as poor work. Hubbard ridiculed Crane's work in The Philistine and edited Shaw's On Going to Church, for which Shaw became Hubbard's lifelong enemy and critic. Hubbard explained to his readers that he had really improved these pieces, but soon no serious author would work with or for him. Although Hubbard later stated in The Philistine that Crane's The Red Badge of Courage would put the young author among the best writers of the age, Hubbard's treatment of true talent destroyed the chance of the Roycroft shop to be a literary fountainhead of the early twentieth century. By 1903 the output of the Roycroft shop became either Hubbard's own titles (more than thirty books by 1915) or the works of those few authors whose outlook he shared. The other names in the annual catalogs of titles continued to be those who would pay for their exposure in print.

As the shops increased in size and operating expenses soared, Hubbard began to accept commercial writing assignments. He would write an essay for any client and print it as a Little Journey. Soon, these exploitive pieces along with his lecturing took all of his time. The time he had regained in the public conscience with A Message to Garcia was running out. He had survived the exposure of his love child in 1901, his divorce from Bertha in 1903, and his marriage to Alice the following year. The essay had spoken of loyalty and getting the job done, not asking why it had to be done or why someone else shouldn't do it. Hubbard's audience of small businessmen and farmers understood that statement of self-reliance. Even though Hubbard had changed from a high-collared business executive with slicked down hair to an aesthete who wore a leather thong to keep long hair in place and who favored an artist's flowing bow tie, he still spoke their language. They were ready to forgive him as an eccentric who shared their roots. But Hubbard had saturated that audience with the same message over the years, and he could not gain new audiences. He spoke for big business when big business was becoming suspect in the public's mind. He defended Standard Oil from Ida Tarbell's attack because John D. Rockefeller was a friend who had a right to conduct his business in his own way. But his old audience did not consider Standard Oil to be a friend. In 1915 the Roycroft enterprise was floundering. The print shop had become just a large commercial printer, and all of the other shops that had produced the craft items were long shut down. The Hubbards announced that they were going to Europe, and Hubbard's last note to his employees said that they "would be gone two months or longer." Elbert and Alice Moore Hubbard died together on the Lusitania, which was sunk by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland.

Hubbard was a paradox. He insisted on being recognized as the guiding genius of Roycroft, but he never interfered in a creative experiment or overruled an employee's decision. He established one of the most pleasant working environments of the time. He paid competitive salaries, instituted morning and afternoon work breaks, and led the workers in physical exercise. He formed and financed a band, a baseball team, and a bank for his employees. He never fired people he deemed unsuitable for his purposes but would give them their pay and a railroad ticket with the suggestion that their career rewards were elsewhere.

The best analysis of Hubbard's influence on his time was made by his friend William Marion Reedy: "It has been said, by myself and others, that Hubbard's appeal is to the half-baked. Culture is relative. People who follow Hubbard do not stay half-baked. They come out of it: he makes lovers of books out of people who never knew books before."

Bibliography

Elbert Hubbard's papers are held by the Elbert Hubbard Museum, East Aurora, N.Y. Material related to Elbert Hubbard and the Roycroft shops is in the Rare Book Room, Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, Buffalo, N.Y. Hubbard authored or coauthored more than thirty books plus the monthly Philistine, Fra, and Little Journey magazines. Some additional works by Hubbard include As It Seems to Me (1898); Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous Women (1898); The City of Tagaste (1900); Contemplations (1902); The Man of Sorrows (1904); Respectability: Its Rise and Remedy (1905); White Hyacinths (1907); William Morris Book (1907).

The best biographies of Elbert Hubbard are Charles Hamilton, As Bees in Honey Drown (1973), and F. Champney, Art And Glory (1968). There is also interesting information in Mary Hubbard Heath, The Elbert Hubbard I Knew (1929), and H. K. Dirlam and E. Simmons, Sinners, This Is East Aurora (1964). The best history of Elbert Hubbard and the Roycroft Printing Shop is Paul McKenna, A History and Bibliography of the Roycroft Printing Shop (1986).

Paul McKenna

Back to the top

Citation:

Paul McKenna. "Hubbard, Elbert Green";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00805.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Jul 22 2013 14:45:15 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

What is Roycroft? It was a handicraft community founded in East Aurora, NY about 1895 by Elbert Hubbard. Hubbard had been a very successful soap salesman for J. D. Larkin and Co. in Buffalo, but wasn't satisfied with his life. So in 1892, he sold his interests in the company and briefly enrolled at Harvard. Disenchanted, he quickly dropped out and set off on a walking tour of England. He briefly met William Morris and became enamored of Morris' Arts-and-Crafts Kelmscott Press.

Upon his return to America, he tried to find a publisher for a series of biographical sketches he had written called "Little Journeys." When he was unsuccessful in his attempts to have someone else publish the works, he decided to print them himself. Thus the Roycroft Press was born. Hubbard proved to be such a prolific and popular writer that fame and fortune soon followed. The print shop expanded and then visitors began coming to East Aurora to see this extraordinary man. Initially, visitors were housed in the printworker's living quarters, but this arrangement soon proved inadequate. A hotel was built to house the ever increasing number of visitors. The inn had to be furnished so Hubbard had local craftsmen make a simple, straight lined style of furniture. The furniture became popular with visitors who wished to buy pieces for their homes. A furniture manufacturing industry was then born. In addition, Roycroft craftspeople were skilled metalsmiths, leathersmiths, and bookbinders.

Philistine Poster

The community flourished and was at its peak in 1910 with over 500 workers. By 1915, Hubbard and the Roycrofters (as the workers were known) had achieved great success. Not only had Elbert written the inspirational pamphlet, A Message to Garcia, with an estimated printing of 40 million copies, but he was also publishing monthly magazines, The Fra and The Philistine. This was all in addition to an almost constant nationwide lecture series and the monthly publication of additions to the original Little Journeys series that started it all.

It all changed when Elbert and his wife, Alice, were among the fatalities onboard the Lusitania. The Hubbards had been traveling to England to begin an lecture tour when they died. The Community's leadership then fell to Elbert's son, Bert. Though Bert took the Roycrofters to wider sales distribution, changing American tastes led to slowly declining sales figures. Finally, in 1938 the Roycrofters closed shop.

Today, items that were produced by the Roycrofters are highly sought after by collectors. In addition to the collectabilty of the items, examples of Roycroft bookbinding, metalsmithing, and furniture-making are sought simply because of their inherent beauty and craftsmanship.

Dot Border

Source: http://www.roycrofter.com/

Person TypeInstitution

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Hudson, Illinois, 1856 - 1915, at sea off Ireland

East Aurora, New York, 1895 - 1938, East Aurora, New York

Portland, Maine, 1838 - 1925, Salem, Massachusetts

Brighton, 1872 - 1898, Menton, France

London, 1830 - 1894, London

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York