Voltaire

Paris, 1694 - 1778, Paris

Heritage And Youth

Voltaire’s background was middle class. According to his birth certificate he was born on November 21, 1694, but the hypothesis that his birth was kept secret cannot be dismissed, for he stated on several occasions that in fact it took place on February 20. He believed that he was the son of an officer named Rochebrune, who was also a songwriter. He had no love for either his putative father, François Arouet, a onetime notary who later became receiver in the Cour des Comptes (audit office), or his elder brother Armand. Almost nothing is known about his mother, of whom he hardly said anything. Having lost her when he was seven, he seems to have become an early rebel against family authority. He attached himself to his godfather, the abbé de Châteauneuf, a freethinker and an epicurean who presented the boy to the famous courtesan Ninon de Lenclos when she was in her 84th year. It is doubtless that he owed his positive outlook and his sense of reality to his bourgeois origins.

He attended the Jesuit college of Louis-le-Grand in Paris, where he learned to love literature, the theatre, and social life. While he appreciated the classical taste the college instilled in him, the religious instruction of the fathers served only to arouse his skepticism and mockery. He witnessed the last sad years of Louis XIV and was never to forget the distress and the military disasters of 1709 nor the horrors of religious persecution. He retained, however, a degree of admiration for the sovereign, and he remained convinced that the enlightened kings are the indispensable agents of progress.

He decided against the study of law after he left college. Employed as secretary at the French embassy in The Hague, he became infatuated with the daughter of an adventurer. Fearing scandal, the French ambassador sent him back to Paris. Despite his father’s wishes, he wanted to devote himself wholly to literature, and he frequented the Temple, then the centre of freethinking society. After the death of Louis XIV, under the morally relaxed Regency, Voltaire became the wit of Parisian society, and his epigrams were widely quoted. But when he dared to mock the dissolute regent, the duc d’Orléans, he was banished from Paris and then imprisoned in the Bastille for nearly a year (1717). Behind his cheerful facade, he was fundamentally serious and set himself to learn the accepted literary forms. In 1718, after the success of Oedipe, the first of his tragedies, he was acclaimed as the successor of the great classical dramatist Jean Racine and thenceforward adopted the name of Voltaire. The origin of this pen name remains doubtful. It is not certain that it is the anagram of Arouet le jeune (i.e., the younger). Above all he desired to be the Virgil that France had never known. He worked at an epic poem whose hero was Henry IV, the king beloved by the French people for having put an end to the wars of religion. This Henriade is spoiled by its pedantic imitation of Virgil’s Aeneid, but his contemporaries saw only the generous ideal of tolerance that inspired the poem. These literary triumphs earned him a pension from the regent and the warm approval of the young queen, Marie. He thus began his career of court poet.

United with other thinkers of his day—literary men and scientists—in the belief in the efficacy of reason, Voltaire was a philosophe, as the 18th century termed it. In the salons, he professed an aggressive Deism, which scandalized the devout. He became interested in England, the country that tolerated freedom of thought; he visited the Tory leader Viscount Bolingbroke, exiled in France—a politician, an orator, and a philosopher whom Voltaire admired to the point of comparing him to Cicero. On Bolingbroke’s advice he learned English in order to read the philosophical works of John Locke. His intellectual development was furthered by an accident: as the result of a quarrel with a member of one of the leading French families, the chevalier de Rohan, who had made fun of his adopted name, he was beaten up, taken to the Bastille, and then conducted to Calais on May 5, 1726, whence he set out for London. His destiny was now exile and opposition.

Exile To England

During a stay that lasted more than two years he succeeded in learning the English language; he wrote his notebooks in English and to the end of his life he was able to speak and write it fluently. He met such English men of letters as Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, and William Congreve, the philosopher George Berkeley, and Samuel Clarke, the theologian. He was presented at court, and he dedicated his Henriade to Queen Caroline. Though at first he was patronized by Bolingbroke, who had returned from exile, it appears that he quarrelled with the Tory leader and turned to Sir Robert Walpole and the liberal Whigs. He admired the liberalism of English institutions, though he was shocked by the partisan violence. He envied English intrepidity in the discussion of religious and philosophic questions and was particularly interested in the Quakers. He was convinced that it was because of their personal liberty that the English, notably Sir Isaac Newton and John Locke, were in the forefront of scientific thought. He believed that this nation of merchants and sailors owed its victories over Louis XIV to its economic advantages. He concluded that even in literature France had something to learn from England; his experience of Shakespearean theatre was overwhelming, and, however much he was shocked by the “barbarism” of the productions, he was struck by the energy of the characters and the dramatic force of the plots.

Return To France

He returned to France at the end of 1728 or the beginning of 1729 and decided to present England as a model to his compatriots. His social position was consolidated. By judicious speculation he began to build up the vast fortune that guaranteed his independence. He attempted to revive tragedy by discreetly imitating Shakespeare. Brutus, begun in London and accompanied by a Discours à milord Bolingbroke, was scarcely a success in 1730; La Mort de César was played only in a college (1735); in Eriphyle (1732) the apparition of a ghost, as in Hamlet, was booed by the audience. Zaïre, however, was a resounding success. The play, in which the sultan Orosmane, deceived by an ambiguous letter, stabs his prisoner, the devoted Christian-born Zaïre, in a fit of jealousy, captivated the public with its exotic subject.

At the same time, Voltaire had turned to a new literary genre: history. In London he had made the acquaintance of Fabrice, a former companion of the Swedish king Charles XII. The interest he felt for the extraordinary character of this great soldier impelled him to write his life, Histoire de Charles XII (1731), a carefully documented historical narrative that reads like a novel. Philosophic ideas began to impose themselves as he wrote: the King of Sweden’s exploits brought desolation, whereas his rival Peter the Great brought Russia into being, bequeathing a vast, civilized empire. Great men are not warmongers; they further civilization—a conclusion that tallied with the example of England. It was this line of thought that Voltaire brought to fruition, after prolonged meditation, in a work of incisive brevity: the Lettres philosophiques (1734). These fictitious letters are primarily a demonstration of the benign effects of religious toleration. They contrast the wise Empiricist psychology of Locke with the conjectural lucubrations of René Descartes. A philosopher worthy of the name, such as Newton, disdains empty, a priori speculations; he observes the facts and reasons from them. After elucidating the English political system, its commerce, its literature, and the Shakespeare almost unknown to France, Voltaire concludes with an attack on the French mathematician and religious philosopher Pascal: the purpose of life is not to reach heaven through penitence but to assure happiness to all men by progress in the sciences and the arts, a fulfillment for which their nature is destined. This small, brilliant book is a landmark in the history of thought: not only does it embody the philosophy of the 18th century, but it also defines the essential direction of the modern mind.

Life With Mme Du Châtelet

Scandal followed publication of this work that spoke out so frankly against the religious and political establishment. When a warrant of arrest was issued in May of 1734, Voltaire took refuge in the château of Mme du Châtelet at Cirey in Champagne and thus began his liaison with this young, remarkably intelligent woman. He lived with her in the château he had renovated at his own expense. This period of retreat was interrupted only by a journey to the Low Countries in December 1736—an exile of a few weeks became advisable after the circulation of a short, daringly epicurean poem called “Le Mondain.”

The life these two lived together was both luxurious and studious. After Adélaïde du Guesclin (1734), a play about a national tragedy, he brought Alzire to the stage in 1736 with great success. The action of Alzire—in Lima, Peru, at the time of the Spanish conquest—brings out the moral superiority of a humanitarian civilization over methods of brute force. Despite the conventional portrayal of “noble savages,” the tragedy kept its place in the repertory of the Comédie-Française for almost a century. Mme du Châtelet was passionately drawn to the sciences and metaphysics and influenced Voltaire’s work in that direction. A “gallery” or laboratory of the physical sciences was installed at the château, and they composed a memorandum on the nature of fire for a meeting of the Académie des Sciences. While Mme du Châtelet was learning English in order to translate Newton and The Fable of the Bees of Bernard de Mandeville, Voltaire popularized, in his Éléments de la philosophie de Newton (1738), those discoveries of English science that were familiar only to a few advanced minds in France, such as the astronomer and mathematician Pierre-Louis de Maupertuis. At the same time, he continued to pursue his historical studies. He began Le Siècle de Louis XIV, sketched out a universal history of kings, wars, civilization and manners that became the Essai sur les moeurs, and plunged into biblical exegesis. Mme du Châtelet herself wrote an Examen, highly critical of the two Testaments. It was at Cirey that Voltaire, rounding out his scientific knowledge, acquired the encyclopaedic culture that was one of the outstanding facets of his genius.

Because of a lawsuit, he followed Mme du Châtelet to Brussels in May 1739, and thereafter they were constantly on the move between Belgium, Cirey, and Paris. Voltaire corresponded with the crown prince of Prussia, who, rebelling against his father’s rigid system of military training and education, had taken refuge in French culture. When the prince acceded to the throne as Frederick II (the Great), Voltaire visited his disciple first at Cleves (Kleve, Germany), then at Berlin. When the War of the Austrian Succession broke out, Voltaire was sent to Berlin (1742–43) on a secret mission to rally the king of Prussia—who was proving himself a faithless ally—to the assistance of the French army. Such services—as well as his introduction of his friends the brothers d’Argenson, who became ministers of war and foreign affairs, respectively, to the protection of Mme de Pompadour, the mistress of Louis XV—brought him into favour again at Versailles. After his poem celebrating the victory of Fontenoy (1745), he was appointed historiographer, gentleman of the king’s chamber, and academician. His tragedy Mérope, about the mythical Greek queen, won public acclaim on the first night (1743). The performance of Mahomet, in which Voltaire presented the founder of Islam as an imposter, was forbidden, however, after its successful production in 1742. He amassed a vast fortune through the manipulations of Joseph Pâris Duverney, the financier in charge of military supplies, who was favoured by Mme de Pompadour. In this ambience of well-being, he began a liaison with his niece Mme Denis, a charming widow, without breaking off his relationship with Mme du Châtelet.

Yet he was not spared disappointments. Louis XV disliked him, and the pious Catholic faction at court remained acutely hostile. He was guilty of indiscretions. When Mme du Châtelet lost large sums at the queen’s gaming table, he said to her in English: “You are playing with card-sharpers”; the phrase was understood, and he was forced to go into hiding at the country mansion as the guest of the duchesse du Maine in 1747. Ill and exhausted by his restless existence, he at last discovered the literary form that ideally fitted his lively and disillusioned temper: he wrote his first contes (stories). Micromégas (1752) measures the littleness of man in the cosmic scale. Vision de Babouc (1748) and Memnon (1749) dispute the philosophic optimism of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Alexander Pope. Zadig (1747) is a kind of allegorical autobiography: like Voltaire, the Babylonian sage Zadig suffers persecution, is pursued by ill fortune, and ends by doubting the tender care of Providence for human beings.

The great crisis of his life was drawing near. In 1748 at Commercy, where he had joined the court of Stanis?aw (the former king of Poland), he detected the love affair of Mme du Châtelet and the poet Saint-Lambert, a slightly ludicrous passion that ended tragically. On September 10, 1749, he witnessed the death in childbirth of this uncommonly intelligent woman who for 15 years had been his guide and counsellor. He returned in despair to the house in Paris where they had lived together; he rose in the night and wandered in the darkness, calling her name.

Later Travels

The failure of some of his plays aggravated his sense of defeat. He had attempted the comédie larmoyante, or “sentimental comedy,” that was then fashionable: after L’Enfant prodigue (1736), a variation of the prodigal son theme, he adapted William Wycherley’s satiric Restoration drama The Plain-Dealer to his purpose, entitling it La Prude; he based Nanine (1749) on a situation taken from Samuel Richardson’s novel Pamela, but all without success. The court spectacles he directed gave him a taste for scenic effects, and he contrived a sumptuous decor, as well as the apparition of a ghost, for Sémiramis (1748), but his public was not captivated. His enemies compared him with Prosper Jolyot, sieur de Crébillon, who was preeminent among French writers of tragedy at this time. Though Voltaire used the same subjects as his rival (Oreste, Sémiramis), the Parisian audience preferred the plays of Crébillon. Exasperated and disappointed, he yielded to the pressing invitation of Frederick II and set out for Berlin on June 28, 1750.

At the moment of his departure a new literary generation, reacting against the ideas and tastes to which he remained faithful, was coming to the fore in France. Disseminators of the philosophical ideas of the time, such as Denis Diderot, the baron d’Holbach, and their friends, were protagonists of a thoroughgoing materialism and regarded Voltaire’s Deism as too timid. Others had rediscovered with Jean-Jacques Rousseau the poetry of Christianity. All in fact preferred the charm of sentiment and passion to the enlightenment of reason. As the years passed, Voltaire became increasingly more isolated in his glory.

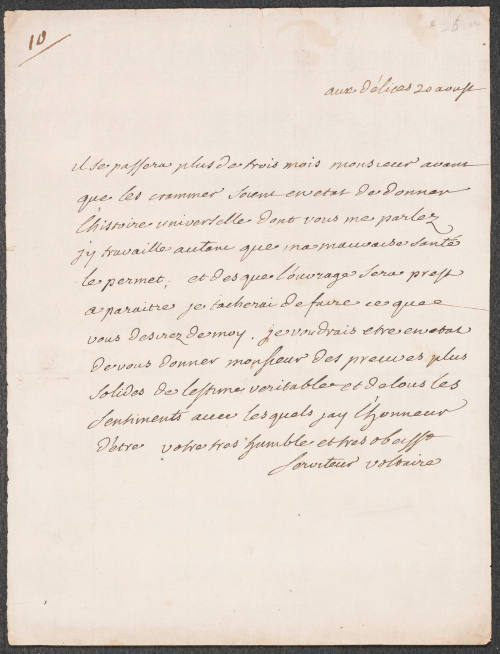

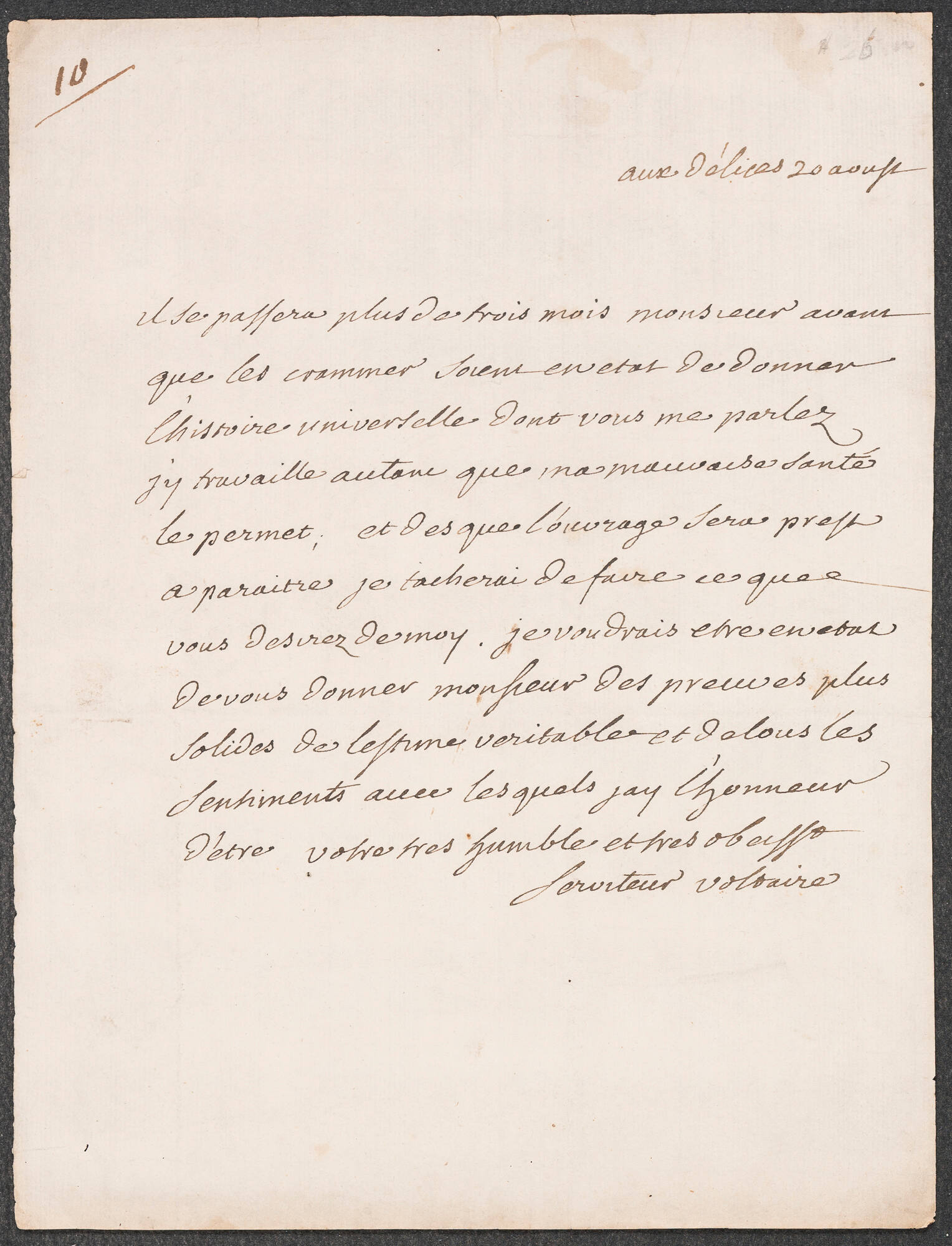

At first he was enchanted by his sojourn in Berlin and Potsdam, but soon difficulties arose. After a lawsuit with a moneylender and quarrels with prominent noblemen, he started a controversy with Maupertuis (the president of Frederick’s academy of science, the Berlin Academy) on scientific matters. In a pamphlet entitled Diatribe du docteur Akakia (1752), he covered him with ridicule. The king, enraged, consigned Akakia to the flames and gave its author a thorough dressing down. Voltaire left Prussia on March 26, 1753, leaving Frederick exasperated and determined to punish him. On the journey, he was held under house arrest at an inn at Frankfurt by order of the Prussian resident. Louis XV forbade him to approach Paris. Not knowing where to turn, he stayed at Colmar for more than a year. At length he found asylum at Geneva, where he purchased a house called Les Délices, at the same time securing winter quarters at Lausanne.

He now completed his two major historical studies. Le Siècle de Louis XIV (1751), a book on the century of Louis XIV, had been prepared after an exhaustive 20-year interrogation of the survivors of le grand siècle. Voltaire was particularly concerned to establish the truth by collecting evidence from as many witnesses as possible, evidence that he submitted to exacting criticism. His desire was to write the nation’s history by means of an examination of its arts and sciences and of its social life, but military events and politics still occupy a large place in his survey. The Essai sur les moeurs, the study on customs and morals that he had begun in 1740 (first complete edition, 1756), traces the course of world history since the end of the Roman Empire and gives an important place to the Eastern and Far Eastern countries. Voltaire’s object was to show humanity slowly developing beyond barbarism. He supplemented these two works with one on Russian history during the reign of Peter the Great, Histoire de l’empire de Russie sous Pierre le Grand (1759–63), the Philosophie de l’histoire (1765), and the Précis du siècle de Louis XV (1768).

At Geneva, he had at first been welcomed and honoured as the champion of tolerance. But soon he made those around him feel uneasy. At Les Délices his presentation of plays was stopped, in accordance with the law of the republic of Geneva, which forbade both public and private theatre performances. Then there was his mock-heroic poem “La Pucelle” (1755), a most improper presentation of Joan of Arc (La Pucelle d’Orléans), which the booksellers printed in spite of his protests.

Attracted by his volatile intelligence, Calvinist pastors as well as women and young people thronged to his salon. Yet he soon provoked the hostility of important Swiss intellectuals. The storm broke in November 1757, when volume seven of Diderot’s Encyclopédie was published. Voltaire had inspired the article on Geneva that his fellow philosopher Jean d’Alembert had written after a visit to Les Délices; not only was the city of Calvin asked to build a theatre within its walls but also certain of its pastors were praised for their doubts of Christ’s divinity. The scandal sparked a quick response: the Encyclopédie was forced to interrupt publication, and Rousseau attacked the rational philosophy of the Philosophes in general in a polemical treatise on the question of the morality of theatrical performances, Lettre à d’Alembert sur les spectacles (1758). Rousseau’s view that drama might well be abolished marked a final break between the two writers.

Voltaire no longer felt safe in Geneva, and he longed to retire from these quarrels. In 1758 he wrote what was to be his most famous work, Candide. In this philosophical fantasy, the youth Candide, disciple of Doctor Pangloss (himself a disciple of the philosophical optimism of Leibniz), saw and suffered such misfortune that he was unable to believe that this was “the best of all possible worlds.” Having retired with his companions to the shores of the Propontis, he discovered that the secret of happiness was “to cultivate one’s garden,” a practical philosophy excluding excessive idealism and nebulous metaphysics. Voltaire’s own garden became Ferney, a property he bought at the end of 1758, together with Tourney in France, on the Swiss border. By crossing the frontier he could thus safeguard himself against police incursion from either country.

Achievements At Ferney

At Ferney, Voltaire entered on one of the most active periods of his life. Both patriarch and lord of the manor, he developed a modern estate, sharing in the movement of agricultural reform in which the aristocracy was interested at the time. He could not be true to himself, however, without stirring up village feuds and went before the magistrates on a question of tithes, as well as about the beating of one of his workmen. He renovated the church and had Deo erexit Voltaire (“Voltaire erected this to God”) carved on the facade. At Easter Communion, 1762, he delivered a sermon on stealing and drunkenness and repeated this sacrilegious offense in the following year, flouting the prohibition by the bishop of Annecy, in whose jurisdiction Ferney lay. He meddled in Genevan politics, taking the side of the workers (or natifs, those without civil rights), and installed a stocking factory and watchworks on his estate in order to help them. He called for the liberation of serfs in the Jura but without success, though he did succeed in suppressing the customs barrier on the road between Gex in the Jura and Geneva, the natural outlet for the produce of Gex. Such generous interventions in local politics earned him enormous popularity. In 1777 he received a popular acclamation from the people of Ferney. In 1815 the Congress of Vienna halted the annexation of Ferney to Switzerland in his honour.

His fame was now worldwide. “Innkeeper of Europe”—as he was called—he welcomed such literary figures as James Boswell, Giovanni Casanova, Edward Gibbon, the prince de Ligne, and the fashionable philosophers of Paris. He kept up an enormous correspondence—with the philosophes, with his actresses and actors, and with those high in court circles, such as the duc de Richelieu (grandnephew of the cardinal de Richelieu), the duc de Choiseul, and Mme du Barry, Louis XV’s favourite. He renewed his correspondence with Frederick II and exchanged letters with Catherine II of Russia.

There was scarcely a subject of importance on which he did not speak. In his political ideas, he was basically a liberal, though he also admired the authority of those kings who imposed progressive measures on their people. On the question of fossils, he entered into foolhardy controversy with the famous French naturalist the comte de Buffon. On the other hand, he declared himself a partisan of the Italian scientist Abbé Lazzaro Spallanzani against the hypothesis of spontaneous generation, according to which microscopic organisms are generated spontaneously in organic substances. He busied himself with political economy and revived his interest in metaphysics by absorbing the ideas of 17th-century philosophers Benedict de Spinoza and Nicolas Malebranche.

His main interest at this time, however, was his opposition to l’infâme, a word he used to designate the church, especially when it was identified with intolerance. For humankind’s future he envisaged a simple theism, reinforcing the civil power of the state. He believed this end was being achieved when, about 1770, the courts of Paris, Vienna, and Madrid came into conflict with the pope, but this was to misjudge the solidarity of ecclesiastical institutions and the people’s loyalty to the traditional faith. Voltaire’s beliefs prompted a prodigious number of polemical writings. He multiplied his personal attacks, often stooping to low cunning; in his sentimental comedy L’Écossaise (1760), he mimicked the eminent critic Élie Fréron, who had attacked him in reviews, by portraying his adversary as a rascally journalist who intervenes in a quarrel between two Scottish families. He directed Le Sentiment des citoyens (1764) against Rousseau. In this anonymous pamphlet, which supposedly expressed the opinion of the Genevese, Voltaire, who was well informed, revealed to the public that Rousseau had abandoned his children. As author he used all kinds of pseudonyms: Rabbi Akib, Pastor Bourn, Lord Bolingbroke, M. Mamaki “interpreter of Oriental languages to the king of England,” Clocpitre, Cubstorf, Jean Plokof—a nonstop performance of puppets. As a part-time scholar he constructed a personal Encyclopédie, the Dictionnaire philosophique (1764), enlarged after 1770 by Questions sur l’Encyclopédie. Among the mass of writings of this period are Le Blanc et le noir (“The White and the Black”), a philosophical tale in which Oriental fantasy contrasts with the realism of Jeannot et Colin; Princesse de Babylone, a panorama of European philosophies in the fairyland of The Thousand and One Nights; and Le Taureau blanc, a biblical tale.

Again and again Voltaire returned to his chosen themes: the establishment of religious tolerance, the growth of material prosperity, respect for the rights of man by the abolition of torture and useless punishments. These principles were brought into play when he intervened in some of the notorious public scandals of these years. For instance, when the Protestant Jean Calas, a merchant of Toulouse accused of having murdered his son in order to prevent his conversion to the Roman Catholic Church, was broken on the wheel while protesting his innocence (March 10, 1762), Voltaire, livid with anger, took up the case and by his vigorous intervention obtained the vindication of the unfortunate Calas and the indemnification of the family. But he was less successful in a dramatic affair concerning the 19-year-old Chevalier de La Barre, who was beheaded for having insulted a religious procession and damaging a crucifix (July 1, 1766). Public opinion was distressed by such barbarity, but it was Voltaire who protested actively, suggesting that the Philosophes should leave French territory and settle in the town of Cleves offered them by Frederick II. Although he failed to obtain even a review of this scandalous trial, he was able to reverse other judicial errors.

By such means he retained leadership of the philosophic movement. On the other hand, as a writer, he wanted to halt a development he deplored—that which led to Romanticism. He tried to save theatrical tragedy by making concessions to a public that adored scenes of violence and exoticism. For instance, in L’Orphelin de la Chine (1755), Lekain (Henri-Louis Cain), who played the part of Genghis Khan, was clad in a sensational Mongol costume. Lekain, whom Voltaire considered the greatest tragedian of his time, also played the title role of Tancrède, which was produced with a sumptuous decor (1760) and which proved to be Voltaire’s last triumph. Subsequent tragedies, arid and ill-constructed and overweighted with philosophic propaganda, were either booed off the stage or not produced at all. He became alarmed at the increasing influence of Shakespeare; when he gave a home to a grandniece of the great 17th-century classical dramatist Pierre Corneille and on her behalf published an annotated edition of the famous tragic author, he inserted, after Cinna, a translation of Julius Caesar, convinced that such a confrontation would demonstrate the superiority of the French dramatist. He was infuriated by the Shakespearean translations of Pierre Le Tourneur in 1776, which stimulated French appreciation of this more robust, nonclassical dramatist, and dispatched an abusive Lettre à l’Académie. He never ceased to acknowledge a degree of genius in Shakespeare, yet spoke of him as “a drunken savage.” He returned to a strict classicism in his last plays, but in vain, for the audacities of his own previous tragedies, timid as they were, had paved the way for Romantic drama.

It was the theatre that brought him back to Paris in 1778. Wishing to direct the rehearsals of Irène, he made his triumphal return to the city he had not seen for 28 years on February 10. More than 300 persons called on him the day after his arrival. On March 30 he went to the Académie amid acclamations, and, when Irène was played before a delirious audience, he was crowned in his box. His health was profoundly impaired by all this excitement. On May 18 he was stricken with uremia. He suffered much pain on his deathbed, about which absurd legends were quickly fabricated; on May 30 he died, peacefully it seems. His nephew, the Abbé Mignot, had his body, clothed just as it was, swiftly transported to the Abbey of Scellières, where he was given Christian burial by the local clergy; the prohibition of such burial arrived after the ceremony. His remains were transferred to the Panthéon during the Revolution in July 1791.

Legacy

Voltaire’s name has always evoked vivid reactions. Toward the end of his life he was attacked by the followers of Rousseau, and after 1800 he was held responsible for the Revolution. But the excesses of clerical reactionaries under the Restoration and the Second Empire rallied the middle and working classes to his memory. At the end of the 19th century, though conservative critics remained hostile, scientific research into his life and works was given impetus by Gustave Lanson. Voltaire himself did not hope that all his vast quantity of writings would be remembered by posterity. His epic poems and lyrical verse are virtually dead, as are his plays. But his contes are continually republished, and his letters are regarded as one of the great monuments of French literature. He bequeathed a lesson to humanity, which has lost nothing of its value. He taught his readers to think clearly; his was a mind at once precise and generous. “He is the necessary philosopher,” wrote Lanson, “in a world of bureaucrats, engineers, and producers.”

CITE

Contributor:

René Henry Pomeau

Article Title:

Voltaire

Website Name:

Encyclopædia Britannica

Publisher:

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.

Date Published:

May 26, 2018

URL:

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Voltaire

Access Date:

August 15, 2018

I.S.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Blackburn, England, 1838 - 1923, Wimbledon, England

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris