Natalie Harris Hammond

Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1859 - 1931, Washington, D.C.

Author

Died: 1931

Books: A Woman's Part In A Revolution, The Boers and the Uitlanders

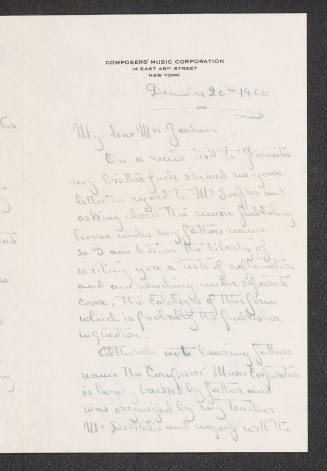

Children: John Hays Hammond Jr.

https://g.co/kgs/ax5pog

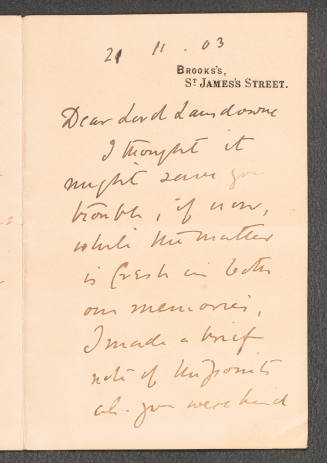

Wife of Hammond, John Hays (31 Mar. 1855-8 June 1936), mining engineer, was born in San Francisco, California, the son of Richard Pindell Hammond, an army officer and politician, and Sara Elizabeth Hays. The scion of a moderately well-to-do family, he graduated from the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale with a Ph.B. in 1876 and then studied for three years at the Königliche Sächsische Bergakademie in Freiberg, Saxony, where a substantial number of important American mining engineers were trained in the nineteenth century. Young Hammond gained experience in jobs typical of those offered neophyte engineers: first as assayer for George Hearst, a major western mine owner, then collecting mineral statistics in California, with the U.S. Geological Survey. In 1881, in Hancock, Maryland, he married Natalie Harris, daughter of a Confederate general; the couple had four children.

Hammond spent the next eight years examining mines throughout the American West and as far afield as Central and South America for individual and corporate capitalists. This work was interrupted when he spent fifteen months as superintendent of a silver mine in Mexico. In 1885 he considerably enhanced his reputation by his skillful reopening of the North Star mine at Grass Valley in California's rich Nevada County. Four years later he took an option on the Bunker Hill & Sullivan in Idaho's Coeur d'Alene district, raised working capital through family and college friends, and took over as president of what became one of the world's most important silver-lead-zinc operations.

In 1893 he joined the growing American mining fraternity in South Africa, first as consultant to the pioneer Barnato brothers, then to Cecil Rhodes, whom he considered the "biggest man I ever met" and "the greatest Englishman of the age." He persuaded Rhodes that in the area later known as Rhodesia the older ancient mines were of great value and should be developed, which was done with dazzling success. On the Witwatersrand in the Transvaal, an incredibly rich area of quartz-pebble conglomerates in South Africa, he convinced Rhodes and others to sell their outcrop mines and develop the deep-level properties adjacent to them, a shrewd appraisal that returned millions.

Hammond described his own work as "more commercial and financial than technical." It was lucrative business, but other engineers believed that the attendant publicity made him "more reputation in So Africa than he would have made in the U.S. in twenty years." Distressed by policies of the dominant Boer minority government--policies Rhodes believed threatened effective mining operations--Hammond joined the Americans and Englishmen in South Africa who plotted an internal revolution. After the failure of Jameson's premature raid across the Transvaal border early in 1896, sixty-four planners of the Reform movement were arrested, and Hammond and three others were sentenced to death for high treason. But the sentences were soon commuted to fifteen years in prison, and Hammond was released after paying a fine of $125,000. Though his African career was over, he left as the best-known mining engineer in the world.

He continued extensive mining dealings, first from London, then from New York. He was one of several invited to survey Russian mineral resources in the winter of 1897-1898 (and again a dozen years later). With a large technical staff under his supervision, he was constantly involved in mine evaluation, sales, promotion, and financing, arguing that the mining engineer was destined to "invade the sphere now monopolized by the employer and capitalist and eventually become, in fact himself, the master." In 1903 he became consulting engineer and general manager of the Guggenheim Exploration Company, created expressly to acquire promising mining properties. In this capacity, he obtained the Utah Copper and Nevada Consolidated, two of the West's most important, new, low-grade copper operations; the Esperanza gold mine in Mexico; and the Central lead mine in Missouri, all of which added to the success of the Guggenheim's powerful American Smelting & Refining Company. Based on a percentage of profits, Hammond's compensation was said to have been $1 million a year, probably twenty to thirty times the income of the average mining engineer.

Though often labeled the "wizard of modern mining" who "could smell a gold mine a thousand miles away," Hammond was not infallible. In 1906, after he enthusiastically endorsed the Nipissing silver mine in Canada, the Guggenheims lost heavily when the property failed to live up to expectations. Pleading poor health, Hammond ended his association with the company in the following year.

While he subsequently became involved in hydroelectric, irrigation, and petroleum projects in California and Mexico, increasingly he turned to "prospecting in politics," as he called it. By his own admission, Hammond knew every president from Ulysses S. Grant to Herbert Hoover, with the exception of Chester A. Arthur, and became enough of an unofficial adviser to William Howard Taft that Colonel House (Edward M. House) could subsequently be referred to as "the John Hays Hammond of the Wilson Administration." He "enjoyed a flutter in the direction of the vice-presidency" with Taft in 1909 but turned down an appointment as minister to China, though he did serve as special ambassador at the coronation of George V in England in 1911. An ardent and active Republican, Hammond developed a strong interest in the settlement of international disputes by judicial arbitration in the pre-World War I era, but he also worked hard in favor of American preparedness and headed Warren G. Harding's commission to survey the coal industry in 1922.

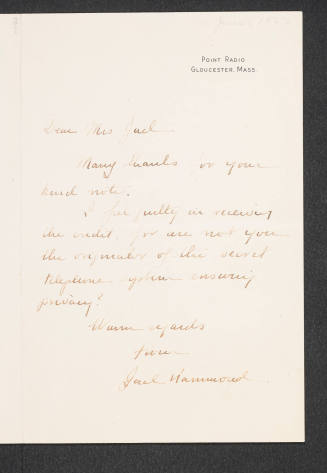

He was elected president of the American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers in 1907 and was awarded its prestigious Saunders Medal in 1929. Early in the century he served as professor at Yale, where he endowed the Hammond Metallurgical Laboratory. He died at his summer home at Gloucester, Massachusetts, and was buried in Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn.

Hammond moved in high social circles. He was a supporter of causes and a joiner of organizations, ranging from the Episcopal church to the twenty-five private clubs to which he belonged in 1931. Ever a spokesman of American business, preaching the standard rags-to-riches message of the gospel of wealth, he also openly espoused such progressive doctrines as woman suffrage and improved labor benefits. This was something of a switch from his early days in Idaho, when he was a leader in quashing the miners' union. By World War I Samuel Gompers could call him "the most conservative, practical, radically democratic millionaire I ever met."

Despite his diminutive physical stature, Hammond was the prototype for Richard Harding Davis's swashbuckling Robert Clay in Soldiers of Fortune (1897). He was a model for inspirational success stories for boys: as one writer said in 1921, "As an empire-builder the name of John Hays Hammond shines with equal splendor alongside those of Henry Hudson, La Salle [René-Robert Cavalier de La Salle], and Cecil Rhodes." His flair for publicity and his lack of modesty made him less popular with many of his fellow engineers, who saw him "as a dynamic but smallish sort of man, ever anxious to appear a little bigger than he was" (quoted in Marshall Bond, Jr., Gold Hunter [1969], p. 214). In truth, he fell somewhere in between: he was an able mining engineer who was more publicized and successful than most. Above all, Hammond was the embodiment of the modern engineer-promoter; with ambition and vision, he understood well his own era and the systematic exploration, large-scale business consolidation, and overseas expansion that were part of it.

Bibliography

The John Hays Hammond Papers are in the Sterling Library, Yale University. Comprising some 6,000 items of correspondence and printed material, this collection deals with South African mining business, the Jameson raid, and Hammond's articles and speeches (1893-1934) on many subjects. The Autobiography of John Hays Hammond (2 vols., 1935) is complete but uneven in quality. A sound appraisal of the African years appears in chapter 5 ("John Hays Hammond and the Jameson Raid: Engineering a Capitalist Revolution in South Africa") of Lysle E. Meyer, The Farther Frontier: Six Case Studies of Americans and Africa, 1848-1936 (1992). Obituaries are in the New York Times, 9 July 1936, and Pope Yeatman, "John Hays Hammond," Mining and Metallurgy 17 (July 1936): 369.

Clark C. Spence

Source:

Clark C. Spence. "Hammond, John Hays";

http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-00691.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Mon Jul 29 2013 14:25:19 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Biography below from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/59167454/natalie-hammond accessed 2/14/19 M Phelps

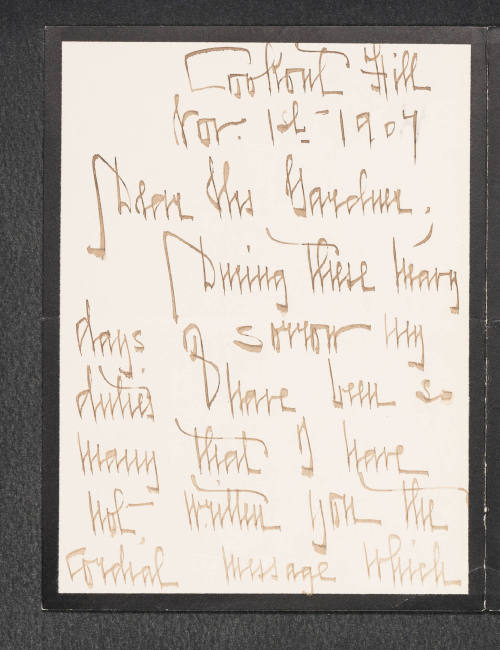

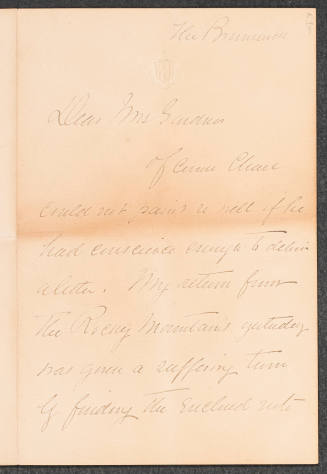

Natalie Harris Hammond was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, the daughter of Judge James Harris and Mary Lum Harris. She met her husband, John Hays Hammond when they were students in Germany. He was an engineering student in Freiburg and she studied music in Dresden. They were married on January 1, 1881 at Hancock, Maryland. She accompanied her husband to Mexico and later South Africa. Her husband and three of his companions who participated in the Jameson Raid were sentenced to death by Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic, with commutation to imprisonment.

We have suffered many hardships in common and during my early life at the mines I have known what it was to be underfed and cold. I have slept with my baby on my breast under a cart in the dust of the highroad. We have traveled together in every known sort of vehicle – bullock wagon, cape cart and private Pullman. For days at a time, my saddle has been the only pillow I have known at night. I have always been my husband’s comrade, his greatest admirer and his best friend.

She was the author of The Boers and the Uitlanders and A Woman’s Part in a Revolution. When her husband was appointed Special Ambassador to England to attend the coronation of King George V in 1911, she acted as his hostess. She founded and was chair of the Women’s Department of the National Civic Federation and was active in prison reform. In 1916 she founded the Militia of Mercy in New York. The organization was instrumental in combating infantile paralysis and treating children of the poor. It later became the official agency for aiding dependent families of volunteer sailors in the American forces. She was also active in the Children’s Christmas Fund, which sent gifts to children of nations at war. In 1912, she co-founded the Women’s Titanic Memorial Association. She came to the District of Columbia with her husband during the administration of President Taft. In 1913, they returned to New York, but returned to the District in 1917, settling in the estate on Kalorama Road. She died on Thursday, June 18, 1931 at her home, 2221 Kalorama Road [currently the official residence of the French Ambassador] after an illness of several weeks. Cause of death was described as a short, severe attack of encephalitis lethargica, known as sleeping sickness. She was predeceased by son, Nathaniel Harris. Survivors included her husband, John Hays Hammond, an internationally renowned engineer; Harris Hammond; John Hays Hammond Jr.; Natalie Hays Hammond and Richard P. Hammond of Paris and one sister, Mrs. Charles Hoyle of the District of Columbia. Private funeral services were held at the home by Rev. Ze Barney T. Phillips, rector of the Church of the Epiphany. Interment was at Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York with Dr. Phillips officiating.

Source: The Evening Star, Thursday, June 18, 1931.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

San Francisco, California, 1888 - 1965, New York City

England, 1896 - 1980, New York

Newport, Rhode Island, 1842 - 1901, Phoenix, Arizona

Giessen, Hesse-Durmstadt, 1854 - 1925, Sturry Court, Kent

Chilvers Coton, Warwickshire, 1819 - 1880, London

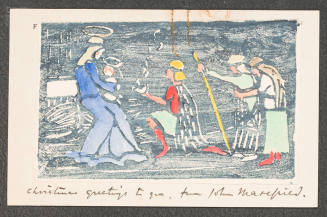

Ledbury, England, 1878 - 1967, near Abingdon, England

Boston, 1846 - 1919, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Salem, Indiana, 1838 - 1905, Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

Wavertree, England, 1850 - 1933, London