Augustus Wollaston Franks

Geneva, 1826 - 1897, London

Biography:

Franks, Sir (Augustus) Wollaston (1826–1897), collector and museum keeper, was born at Geneva on 20 March 1826, the eldest of six children (two sons and four daughters) of Frederick Franks (1793/4–1844), naval officer, and his second wife, Frederica Anne (d. 1864), daughter of Sir John Saunders Sebright and his wife, Harriet Crofts. His godfather was William Hyde Wollaston, a friend of his mother's family. His mother was the sister of his father's first wife, Emily Saunders Sebright (d. 1822). Although not illegal, the marriage (which took place in New York on 12 July 1824) was voidable and considered improper. It may be for this reason that Franks's father chose to live abroad (he had relatives—the Gaussens—in Geneva). Franks's family moved to Rome in 1828 and did not return to London until 1843.

Franks was well connected and comparatively rich. His mother was an heiress; her father had married an heiress; and Franks's cousin was the third earl of Harewood. His father came from a banking family: his great-grandfather had married a Pepys, while his grandmother was of rich Huguenot descent (her father had been a director of the Bank of England and governor of the East India Company). On both sides of the family there were collectors; his father collected pictures and his mother minerals, and he was even distantly related to that other benefactor of the British Museum, Richard Payne Knight.

Franks was educated at Eton College (1839–43) and at Trinity College, Cambridge (1845–9). His father having died and left him a ‘sufficient fortune’ by the time he went up to university, he decided to read for an ordinary degree and devoted his time to antiquarian studies. He was one of the founders of the Cambridge Architectural Society and a member of the Ray Society and of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society. Franks published, while still an undergraduate, an account of a palimpsest brass at Burwell (1847), an extensive paper on the Freville family (1847), and a small and much quoted book on medieval glazing quarries illustrated from his own drawings (1849). All this work showed the influence of the Cambridge Camden Society (later the Ecclesiological Society), of which he was a member, and foreshadowed many of his later interests.

Franks moved to London in 1849, and became very influential in the newly founded Archaeological Institute, where he organized the annual exhibitions and gained a deep knowledge of European antiquities. He was honorary secretary to the organizing committee of the medieval exhibition held at the Royal Society of Arts in 1850, and, as a result of this work, was appointed to a newly established post at the British Museum to oversee the establishment of a collection of British antiquities, which had been recommended by a royal commission in 1850. Under the supervision, and with the support, of Edward Hawkins, keeper of antiquities, and with the encouragement of his successor, Samuel Birch, Franks set about the creation of a collection that was ultimately to result in the formation of five of the departments of the present-day British Museum (medieval and later, prehistoric and Romano-British, ethnography, oriental, and Japanese). In 1866 he became keeper of the newly created department of British and medieval antiquities and ethnography.

Franks already had a formidable reputation as a scholar. He wrote many pithy notes in the Archaeological Journal, and had published books on oriental glass and enamels (1861) and on Arabian inscriptions (1863), but his most important work was his contribution to Kemble's Horae ferales, which in 1858 broke new ground in prehistory, for example by recognizing for the first time the La Tène culture. The breadth of his interests and knowledge increased throughout his life and he wrote papers and books on subjects as diverse as Indian sculpture, Japanese prehistoric flints, Hans Holbein, Anglo-Saxon rings, Chinese paintings, bookplates, megalithic monuments in the Netherlands, and many more.

This output reflected his collecting interests, both personal and public. Because of his wealth he could afford to buy with his own money for the museum, often with the purpose of encouraging the trustees to spend their money on similar material. Typical of his modus operandi was the way in which he persuaded the museum to collect Italian maiolica. Within a few months of his arrival at the museum, he purchased for himself twenty-one maiolica dishes from the collection of the Abbé James Hamilton; he then purchased another two major items, so that when the great Bernal collection came on to the market in 1855 he was able to offer his pieces to the museum as bait so that the trustees could approach the Treasury for a grant to buy maiolica and much else at the sale (the trustees received £4000 for this purpose). Later he was to do this on a grander scale, offering, for example, to give the museum material equivalent in value to the grant they had applied for (£3000) to purchase items at the Fountaine sale of pottery and porcelain in 1884. In the case of the royal gold cup of the kings of France and England, his most prestigious acquisition, he made the purchase for £8000 and then appealed to friends to help him with cash so that he could give the cup to the museum. Throughout his long life he built up his own collections and enriched the museum from his own generosity. On his death he bequeathed the whole of his collection—some 3300 objects—to the British Museum. He also gave or steered other objects to other museums, and particularly to the Victoria and Albert Museum. He gave two paintings to the National Gallery and his great collection of brass rubbings to the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Franks also attracted gifts, the most important of which was the great collection of Henry Christy, which in effect formed the foundation of the British Museum's ethnographic collection. This was left in trust to a small body of men, of whom one was Franks, who steered it to the museum. At first it was housed in Victoria Street and Franks paid out of his own pocket for its first curator, Charles Hercules Read, and for an illustrator. He also added to this collection at his own expense (he reckoned to have spent £5000 on American and Asian items) and out of a small fund left by Christy; particularly splendid were his additions of the pre-Columbian turquoise masks and Afro-Portuguese ivories.

Other great collections came in similar ways. They included: the glass of Felix Slade; the Indian sculpture collection of Hindoo Stuart from the Bridge family; the clocks and scientific instruments of Octavius Morgan; his own collection of armorial bookplates (which incorporated a small part of the de Tabley collection); the residue of the Meyrick collection; the playing cards of Lady Charlotte Schreiber (better known as Lady Charlotte Guest); the Bähr collection of Livonian antiquities; and the India Museum's sculpture collection. Smaller collections were also acquired, such as that of the Danish state antiquary J. J. A. Worsaae, the medieval collections of the architect William Burges, and many more.

Two or three major objects given by Franks to the museum deserve special mention. The ‘Franks Casket’, recovered by a Paris dealer from a kitchen drawer in Auzun, is one of the most important runic-inscribed objects of the Anglo-Saxon period. Dated to the eighth century, it is made of whalebone and is carved with scenes from a universal history in a style otherwise unknown in Britain. The ‘Treasure of the Oxus’ is one of the most intriguing of his donations. Buried perhaps about 200 BC, the largest part of it is considered to be an accumulated temple treasure of the Achaemenian Persians, consisting of silver and gold plate (much of it decorated with fabulous beasts), and some 1500 gold and silver coins. Franks also acquired the museum's only serious piece of prehistoric Japanese Haniwa sculpture.

Although a lifelong bachelor, Franks was a sociable—if shy—man. He attached great importance to his club (the Athenaeum) and moved in the governing circles of his day. He was well known abroad and was a fervent supporter of the International Congress of Archaeology and Anthropology and attended most of its early meetings. He travelled widely in Europe (but apparently not outside it), and his travels fed his collections. He was a leading authority on European heraldry and might well be described as the first professional prehistorian. He was much sought after to sit on international committees, and was director (and later president) of the Society of Antiquaries, to which he left many books. He was created KCB in 1894, was an honorary doctor of both Oxford and Cambridge, a fellow of the Royal Society, antiquary to the Royal Academy, and (after his retirement in 1896) he was made a trustee of the British Museum and a member of its standing committee.

Despite his apparent worldliness, Franks in personal terms remains an enigma. He was neatly bearded and dapper, and was a neat dresser, but he hated public appearances and public speaking, and few descriptions of him survive. Dame Joan Evans's childhood memory of being given a piece of lapis by Franks; a description of him weeding the lawn outside his residence in the British Museum, while the children of other keepers played cricket on the other lawn; a Christmas in Brussels with Lady Charlotte Schreiber, with whom he visited the dealers in that town: these provide rare glimpses of his private life. Little is known of his relationship to his family, but he looked after his sister Frederica and she was buried with him in his grave. Joan Evans, whose father, John Evans, was one of Franks's oldest friends, provides us with a neat word-portrait:

He was ... a grey dreamy person, with an unexpected dry humour and an incurable habit of addressing himself to his top waistcoat button. These buttons, indeed, served as a barometer of enthusiasm. If he were looking at an antiquity he liked very much indeed, he fingered the top button; if very much the next; if moderately the next and so on down the scale. There were few objects of antiquity which failed to evoke a response of some sort, for his knowledge was incredibly wide. (Evans, 143)

Franks was conservative in thought, a traditionalist, deeply dedicated to the museum and particularly to the department that he had created. This was so much the case that he refused the principal librarianship of the British Museum in 1874 and the directorship of the South Kensington Museum twice. Although he had friends in the museum (Sir Charles Newton, for example), he was clearly aloof from many of his younger colleagues, with the exception of Read, who was his successor as keeper and the executor of his estate. He was very friendly with John Evans and through him presumably knew many of the intellectual aristocracy of the mid-Victorian period. He also knew and corresponded with his foreign contemporaries, Lartet, Worsaae, Lindenschmidt, Nilsson, Khanikoff, Vogt, and Schliemann. But despite his extended and deep interest in archaeology and anthropology, he was clearly more at home with his fellow rich or aristocratic collectors, including Charlotte Schreiber, Lord Londesborough, W. E. Gladstone, Sir John Lubbock, and Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild.

In many respects Franks was the second founder of the British Museum. Through his energy and dedication he created the core of its non-classical or eastern Mediterranean collections of antiquities. He fought skilful battles against reluctant and parsimonious trustees and Treasury protectionism. He seized the opportunity of the move of the Natural History Museum to South Kensington to install the collections under his care more spaciously. Writing at the end of his life, he was able to quantify his contribution to the museum's growth:

When I was appointed to the Museum in 1851 the scanty collections out of which the department has grown occupied a length of 154 feet of wall cases, and 3 or 4 table cases. The collections now occupy 2250 feet in length of wall cases, 90 table cases and 31 upright cases, to say nothing of the numerous objects placed over the cases or on walls. (Franks)

To this are to be added the archaeological and other reserve collections and Franks's own collection, which was to come to the museum in 1897 as his bequest. He was a professional museum man as well as a distinguished scholar, aware of the importance of records and inventories (although curiously little of the documentation of his own collections survives). He was experienced in exhibition technique and was consulted both in Britain and abroad on museum matters. He was keen on publication of the collections in his area and himself wrote a number of catalogues.

Franks's own tastes in collecting tended to shape the collecting policy of the British Museum for the next century. He was very much a collector of material from dealers, particularly single items or small collections of portable material. For the museum he would acquire larger collections, but very much of the same sort of material. With the exception of ethnographic material he collected little sculpture, apart from the great Indian collections, which clearly fascinated him at a period when they were of little interest to anybody else. He left all European sculpture collecting to the South Kensington Museum. They also collected furniture and the British Museum consequently has none. He put a lot of energy into collecting pottery and porcelain on a historical basis and much of his material was less than fifty years old when he bought it. He did not buy prestige pieces, Berlin or St Petersburg porcelain vases for example, but left this to South Kensington. He collected historic silver and gold plate with great discernment, and his interests in archaeology meant that the museum acquired vast ranges of excavated material from throughout Europe. He was one of the earliest museum collectors to recognize the importance of ethnographic material and he bought in this area almost exclusively for the museum and not for himself, although he spent a lot of his own money on it. He was deeply knowledgeable about the material culture of the Far East and collected widely and well, including the earliest Japanese porcelain to be imported into Europe at the time of the Edo opening up of trade to the West.

Franks died of cancer of the bowel on 21 May 1897 at 11 Duchess Street, Portland Place, London, and was buried in Kensal Green cemetery. His name is today known to only a few specialists, yet he was as important to the museums of Britain (and particularly to the British Museum) as was Bode to Berlin and the German national collections.

David M. Wilson

(“Franks, Sir (Augustus) Wollaston (1826–1897),” David M. Wilson in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, eee ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: OUP, 2004); online ed., ed. Lawrence Goldman, May 2014. Accessed August 15, 2015. www.oxforddnb.com)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

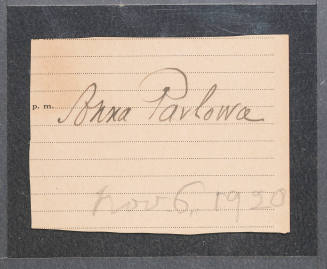

St. Petersburg, 1881 - 1931, Hague, Netherlands

Deep River, Connecticut, 1868 - 1953, Princeton, New Jersey

Hyde Park, Massachusetts, 1869 - 1934, New York

Cincinnati, Ohio, 1853 - 1935, London

Doylestown, Pennsylvania, 1856 - 1930, Doylestown, Pennsylvania

Germantown, Pennsylvania, 1864 - 1945, Florence

Chester, England, 1846 - 1886, Saint Augustine, Florida