Frederic George Stephens

London, 1828 - 1907, Hammersmith

Stephens, Frederic George (1827–1907), art critic and art historian, born on 10 October 1827, was the son of Septimus Stephens of Aberdeen and the grandson of Octavius Stephens of Dublin; his mother was possibly named Ann Cooke. Stephens's father was an official at the Tower of London and the family lived in Lambeth. A childhood accident in 1837 left Stephens lame, and he was educated at home with a private tutor and at University College School in London. Determined to be an artist, he entered the Royal Academy Schools on 13 January 1844, at the age of sixteen: here he made the acquaintance of John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, with whom he joined to found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. Stephens's beautifully shaped head and fine features made him much in demand as a model for his fellow artists: he can be recognized as the central figure in Millais's Ferdinand Lured by Ariel (1849; Makins collection) and in Ford Madox Brown's Jesus Washing Peter's Feet (1856; Tate collection). Realizing that he would not succeed as a painter, he attempted to destroy all of his pictures in the late 1850s, and only six works of art—now in the Tate collection and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford—escaped his wrath.

Stephens found more success as an art critic and art historian, becoming the leading art critic for The Athenaeum for forty years until Roger Fry replaced him in 1901. To supplement his income he also wrote as a freelance contributor over 100 articles for British, French, German, and American publications. As an art historian, he produced a number of publications, among which featured monographs on British artists—including Edwin Landseer (1869), William Mulready (1867), and Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1895)—and historical surveys, such as Flemish Relics (1866) and Normandy: its Gothic Architecture and History (1865). Also included were catalogues of exhibitions at the Grosvenor Gallery and the Fine Art Society, and the first four volumes of the British Museum catalogue of satirical prints and drawings. Taken together, his writings in art criticism and art history established a rudimentary methodology for the study of modern British art, contributed to the growing Victorian taste for contemporary art, and encouraged middle-class patronage.

Stephens's close association with the Pre-Raphaelites coloured his early reviews, although he eventually managed to broaden his opinions. Loyal to his artist colleagues, he made every effort to bring their work to the attention of the public and to articulate their goals. To clarify the confusion which still surrounded the name ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ in 1862, Stephens explained:

Declaring that the followers of Raphael had ruined the art, simply because they were followers of Raphael, and not humble students of nature ... the P.-R.B., with characteristic audacity, and with a seriousness which was half veiled in the fantastic assumption of their society's peculiar title, determined that their own works should show a different motive in art. (‘Men of mark—no. xxix: John Everett Millais’, London Review, 22 Feb 1862, 183)

He went on to champion the paintings of Millais, Hunt, and the elusive Dante Gabriel Rossetti throughout the 1860s and 1870s. It was not until the next decade, almost forty years after the founding of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, that he managed to put their art into perspective.

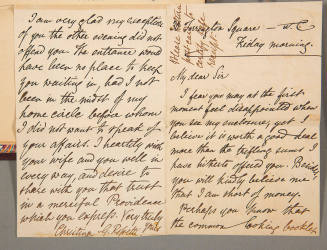

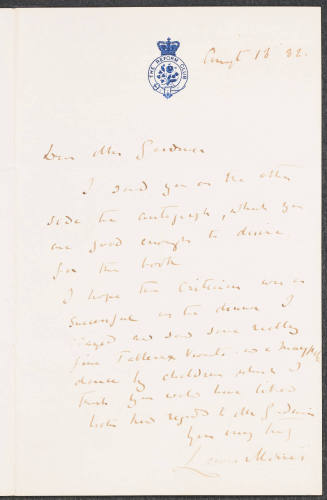

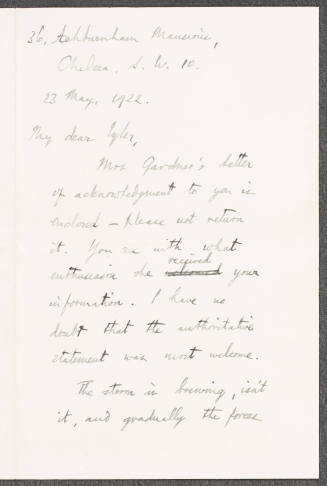

Rossetti's death in 1882 freed Stephens from the brotherhood's filial bond. Somewhat intimidated by the domineering artist, he had allowed Rossetti to vet everything he wrote about him in The Athenaeum; their unpublished correspondence reveals the extent to which the artist dictated to the critic. Among Stephens's papers in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, are descriptions of Rossetti's paintings in Dante Gabriel's own hand which Stephens faithfully followed, telling the artist, ‘I will use your notes for a text of my own if you like, or simply copy them before they go in to be printed’ (F. G. Stephens to D. G. Rossetti, Rossetti letters, Angeli-Dennis collection, University of British Columbia). Thus the critical tone Stephens adopted following the artist's death presents a remarkable contrast: when he complained that Rossetti's art frequently revealed ‘signs of impatience and weariness’ (‘The Royal Academy—Winter Exhibition’, The Athenaeum, 2880, 6 Jan 1883, 22), he may very well also have been describing his own response to having been manipulated by him for years.

Stephens likewise introduced a carping note into his coverage of the posthumous exhibition of Millais's art in 1898 which was in jarring contrast to his earlier favourable reviews: he now found fault with the artist's ‘crude and hasty manner’ (‘The Royal Academy—Winter Exhibition: Works of Sir John E. Millais’, The Athenaeum, 3663, 8 Jan 1898, 57). While it might seem that Stephens was afraid to criticize his Pre-Raphaelite colleagues while they were alive, he proved his mettle when he wrote two devastating reviews of William Holman Hunt's Triumph of the Innocents (1876–85; Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). Disturbed by the representation of heavenly children floating in space like bubbles, he accused the artist of combining idealism and realism in a ‘self-contradictory and puzzling’ manner (‘Holman Hunt's The triumph of the innocents’, The Portfolio, 16 April 1885, 81). Moreover, Stephens blamed Hunt for taking the Pre-Raphaelite dogma of truth to nature to an extreme. He complained that the artist was ‘concerned with the development of one idea, to which he has clung ... with astonishing tenacity’ (‘Mr. W. Hunt's pictures in Bond Street’, The Athenaeum, 3048, 27 March 1886, 428). Hunt never forgave him for these remarks and added a diatribe against Stephens as an appendix to the second edition of his Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1914. Stephens's comments, however, should be viewed in the larger context of the evolutionary theory of artistic development that he had gradually come to formulate.

By the 1880s Stephens was conscious that he was writing as an ‘art-historian’ in a ‘new branch of knowledge’ (F. G. Stephens, Flemish and French Pictures with Notes Concerning the Painters and their Works, 1875, v). He concentrated on identifying and classifying patterns of growth, frequently employing a tripartite mode of explanation. His exposure to a wide range of artists at the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy and the Paris salons led him to recognize Pre-Raphaelitism's place in the history of British art: he came to see the efforts of the brotherhood as a progressive outgrowth from the natural impulse represented by earlier Victorian genre painters such as William Mulready, Augustus Egg, William Dyce, and William Henry Hunt. In several important essays which he wrote for H. D. Traill's six-volume Social England: a Record of the Progress of the People (1893–7), Stephens acknowledged Pre-Raphaelitism's debt to previous British artists and asserted that it was less avant-garde than was often claimed.

One aspect of Stephens's philosophy which did not change over time was his belief that art should not be élitist. He dedicated much of his energy to promoting the cause of inexpensive prints, beginning in 1859 when he argued that ‘the essentials of good art may be produced at a very minute cost’ (‘Cheap art’, Macmillan's, 1 Nov 1859, 48). Additionally, he wrote about the graphic artists Thomas Rowlandson, Thomas Bewick, and George Cruikshank, and spent almost twenty-five years compiling a four-volume catalogue of the British Museum's satirical prints and drawings. Consistent with his egalitarian views of art is the ninety-part series on private collecting that he published in The Athenaeum (1873–87), in which he featured aristocratic collections alongside those formed by little-known businessmen. He saved his highest praise for collectors who bought judiciously and inexpensively and who preferred modern British art. Stephens made no secret of his admiration for the new breed of collector, pronouncing that ‘The so-called middle-class of England has been that which has done the most for English art’ (‘English painters of the present day, XXI: William Holman Hunt’, The Portfolio, 2 March 1871, 38). Although Stephens continued to advance the cause of middle-class patronage of modern art from his lofty podium at The Athenaeum, his flowing white beard and conservative opinions marked him at the end of his tenure in 1901 as a man who was out of touch with his times. He detested impressionism and therefore did not write about collections containing contemporary French art. None the less, as an expert on British art he continued to be consulted by a variety of publications until 9 March 1907, when he quietly passed away at his desk at his home, 9 Hammersmith Terrace, London. He was buried on 14 March in Brompton cemetery. Stephens had married, on 8 January 1866, Rebecca Clara (b. 1833/4), daughter of Riley Dalton, a contractor. She survived him, as did their son, Holman Stephens. Stephens's collection of engravings, etchings, and books was sold on 18–19 October 1916 at Fosters, following his widow's death.

Dianne Sachko Macleod

(“Stephens, Frederic George (1827–1907),” Dianne Sachko Macleod in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, eee online ed., ed. Lawrence Goldman, Oxford: OUP, 2004, Accessed August 28, 2015.www.oxforddnb.com)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Great Yarmouth, 1824 - 1897, London

Edinburgh, 1811 - 1890, Aryshire, Scotland

London, 1830 - 1894, London

Carmarthen, Wales, 1833 - 1907, Llangunnor, Wales

Philadelphia, 1829 - 1914, Philadelphia

Naini Tal, India, 1851 - 1939, Brighton