Elsie de Wolfe

New York, 1865 - 1950, Versailles

When she returned to New York in 1884, she began to perform in amateur theatricals, becoming a professional actress in 1890, after her father's death left her with little money. She achieved a modest success during her fourteen-year acting career but was best known for her stylish couturier clothes on the stage. During this period she lived with Elisabeth Marbury (Bessie), who established herself as the leading theatrical and literary agent of her day.

It was at their house on Irving Place that de Wolfe began to experiment with her taste and ideas of interior decoration. She transformed the dark Victorian interior into a prototype of twentieth-century decoration by stripping away the clutter and replacing heavy furniture with eighteenth-century-style French pieces. From there she launched her career as America's first professional woman interior decorator. Backed by numerous wealthy, influential women, such as Anne Morgan, the daughter of the banker J. P. Morgan, Anne Vanderbilt, and the Hewitt sisters, Sarah and Eleanor, her business was an immediate success.

In 1905 de Wolfe received her first major commission, to decorate the rooms of the Colony Club, an exclusive New York women's club whose architect, Stanford White, had been instrumental in obtaining the job for her. To impart an atmosphere of light and air, she introduced a number of decorative innovations that became her trademarks: flowered chintz or toile de Jouy fabrics in the bedrooms and sitting rooms, cream-colored furniture, the liberal use of mirrors, and the use of interior trellis work. De Wolfe's ideas of interior decoration were not original. By the turn of the century the resurgence of classical and colonial revival taste had led to the lightened appearance of rooms in general. Her taste and style were influenced by Ogden Codman, architect and decorator who advised her and collaborated with her on several houses. Codman's groundbreaking The Decoration of Houses (1897), written with Edith Wharton, called for the elimination of heavy draperies, knickknacks, and poorly designed furniture. Their credo--suitability, simplicity, and proportion--was popularized by de Wolfe in The House in Good Taste (1913). She directed her book at the emancipated American woman and imparted practical as well as artistic advice. Her emphatic claim that the decoration of the home belonged under the woman's domain did much to spawn the acceptability of decorating as a suitable occupation for women.

De Wolfe decorated residences and apartments throughout the country; some of her most notable commissions were for Henry Clay Frick of New York, Mrs. J. Ogden Armour of Chicago, Mrs. William Crocker of San Francisco, and Mrs. R. M. Weyerhaeuser of Minneapolis. Few, if any, of her interiors have survived.

As her career prospered, she spent increasingly more time at "Villa Trianon," the eighteenth-century house in Versailles that she and Elisabeth Marbury bought and restored, with the aid of Anne Morgan, in 1903. Drawn to novelty of all sorts, she was one of the first women to accompany Wilbur Wright on some of his test flights in 1908. She remained in France throughout the First World War and nursed the wounded, for which she was awarded the Legion of Honor. During the 1920s she maintained offices on both continents; her business acumen and flair for entertaining and self-promotion established her reputation as an international hostess. In 1926, at age sixty, she married Sir Charles Mendl, an attaché of the British embassy, and continued to stage extravaganzas at her residences in Paris and Versailles. When Villa Trianon was made a Nazi headquarters during the Second World War, Lady Mendl, as she was known after her marriage, and her husband fled to Hollywood, where she continued to be a trendsetter and hostess "extraordinaire." She is remembered for her individual sense of style as well as her contribution to fashion. She was never without white gloves and always maintained her fastidious appearance; she made it fashionable for older women to tint their hair blue. She returned to France after the war and died there at her home. Her success as a career woman led the way for the acceptance of American women in the professional world.

Bibliography

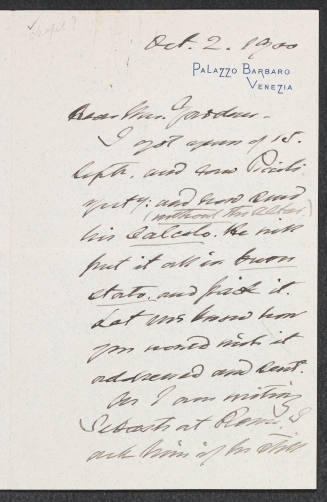

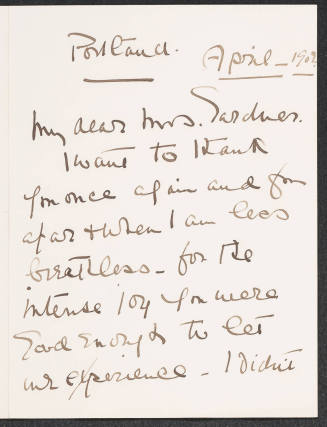

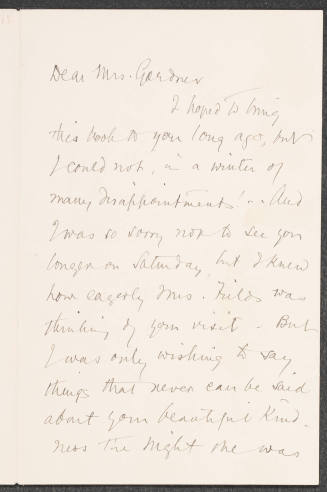

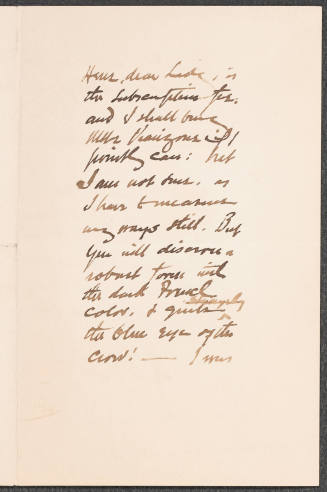

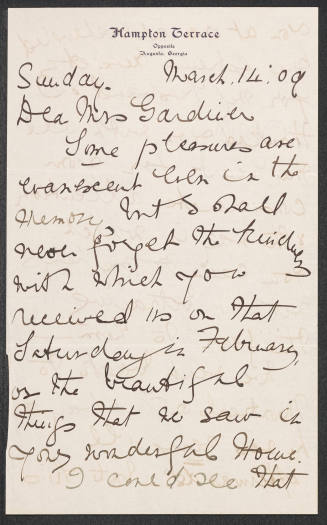

Personal letters, scrapbooks, inventories of collections, and other memorabilia belong to the Elsie de Wolfe Foundation in Los Angeles. For her childhood, youth, and career on the stage, see clippings in the Players Collection and the Robinson Locke Scrapbooks in the Theatre Collection of the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center. Her autobiography is After All (1935); see also the autobiography of Elisabeth Marbury, My Crystal Ball (1923). The biography of Elsie de Wolfe, including extensive references, is by Jane S. Smith, Elsie de Wolfe, a Life in the High Style (1982). For her decorating ideas, see her book, The House in Good Taste (1913). See also Ruby Ross Goodnow, "The Story of Elsie de Wolfe," Good Housekeeping, June 1913. For information on her later life, see Janet Flanner, An American in Paris (1940), and Ludwig Bemelmans, To the One I Love the Best (1955). Obituaries are in the New York Herald Tribune and the New York Times, 13 July 1950, and Le Monde (Paris), 14 July 1950.

Pauline C. Metcalf

Back to the top

Citation:

Pauline C. Metcalf. "de Wolfe, Elsie";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00215.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:20:17 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Boston, 1825 - 1908, Venice

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1879 - 1959, Los Angeles, California

South Berwick, Maine, 1849 - 1909, South Berwick, Maine

London, 1843 - 1932, Godalming, England

Philadelphia, 1864 - 1916, Mount Kisco, New York

Boston, 1881 - 1968, Palm Beach, Florida

Montreal, Quebec, 1860 - 1942