Alexander Agassiz

Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 1835 - 1910, at sea aboard the RMS Adriatic

Agassiz, Alexander (17 Dec. 1835-27 Mar. 1910), marine biologist, oceanographer, and industrial entrepreneur, was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, the son of Louis Agassiz, a zoologist, and Cécile Braun. Agassiz came to the United States in 1849, following the death of his mother in Germany. The domestic life of his parents had been marred by difficulties, and Alex moved to Massachusetts to join his father, who had become a professor of zoology and geology at Harvard University after a distinguished career in Europe. The American experience came at a difficult stage in Alex Agassiz's adolescence. He hardly knew his father, who had spent much time away from home on scientific projects.

The Agassiz family solidified when Louis Agassiz married Elizabeth Cabot Cary in 1850, and Alex's sisters Ida and Pauline joined the family. "Lizzie" Cary was consistently a devoted, loving, and supportive stepmother, and Agassiz was deeply devoted to her.

In 1860 Agassiz began a lifetime occupation of administering the business affairs of the Harvard museum, a task made difficult by his father's penchant for excessive collecting and expenditures. After Louis's death in 1873, Agassiz succeeded to the directorship of the museum and completed the physical plan of the building.

While a museum administrator, Agassiz was able to do significant research and publication in marine biology, especially in the study of Echinoderms (starfish, sand dollars, sea urchins, sea lilies, and related forms). The Embryology of the Starfish (1864) was an early mark of his capability in this new branch of science. It was followed by Revision of the Echini (1872-1874), a three-volume, beautifully illustrated work analyzing most known forms in Europe and America and detailing their geographical distribution, embryology, and natural history. The work remains his most distinguished contribution, and it won him many admirers in Europe and America.

The amalgamation of the Agassiz family into the rich and powerful culture of Brahmin New England was rapid and remarkable. After Louis's marriage to Cary, the daughter of a prominent family, Alex did the same by marrying Anna Russell in 1860; his best friend and fellow naturalist, Theodore Lyman, thereby became his brother-in-law. This pattern was completed when Ida and Pauline Agassiz married Henry Lee Higginson and Quincy Adams Shaw, respectively.

In 1866 Quincy Shaw persuaded Alex to go to Michigan's upper peninsula and evaluate unproductive copper properties in which he was a substantial investor. Agassiz, employing engineering and management skills, completely reorganized the enterprise. In 1871 the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company was founded with Agassiz as president, a post he held until 1901. His astute management, coupled with the fabulously rich copper deposits, made the closely held Calumet and Hecla company the richest in the world. Agassiz became a millionaire several times over, and many of the Boston elite were indebted to him for their new wealth.

Now entirely independent of the ordinary pressures of his profession, Agassiz could write and study as he pleased. He gave over a million dollars to complete the Harvard museum, fulfilling his father's dream. Conservative and devoted to order, precision, and planning, he differed from his father in manner and personality but defended him against those who attacked his views, in life and posthumously.

In 1873, after the death of his father and of his wife within a few weeks of each other, Agassiz felt as if a cloud had fallen over his life, and a severe melancholy always seemed to burden him as he raised three sons and saw to his stepmother's needs. He began to spend much time in a beautiful house he had built in Newport, Rhode Island, where the tasteful furnishings and quite natural surroundings provided relief from directing the museum and the world of business affairs.

Although he was a friend of Charles Darwin, Agassiz's relationship to the evolution concept was complicated by his strong intellectual conservatism. He abjured the dogmatic opposition of his father and held that the "theory of evolution has opened up new fields of observation in many departments of biology." Evolution did not, however, play a large role in his scientific work. He reacted negatively to the radical Darwinists of his day, urging colleagues "to wait quietly in this time of transition," avoiding the blandishments of those who would engage in "high flights" of imagination and build "castles in the air." He argued that doing "a little hard work" would be more useful than engaging in wild speculation (Agassiz, Letters and Recollections of Alexander Agassiz, pp. 123, 163-64). Open minded to all new evidence, yet avoiding extremes, Agassiz could not be counted as an adherent to the Darwinian doctrine.

Agassiz published more than 150 articles and books, mainly on his favorite echinoderms and related groups. In the 1870s Sir John Murray, scientific director of the world-renowned British expedition of HMS Challenger, asked Agassiz to describe and analyze the echini collected by Challenger in its exploration voyage around the world. The result, his Report on the Echinoidea (1881), was a primary contribution to both marine biology and knowledge of geographical distribution. Agassiz's works appeared mostly in the serial publications of the Harvard museum. As director he published without the barriers of peer review, a practice that may have dimmed his ultimate reputation, though, in Agassiz's lifetime, that reputation was unchallenged. A president of the National Academy of Sciences and active in the affairs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, he was admired by such naturalists as Asa Gray, James Dwight Dana, Jeffries Wyman, Darwin, and Thomas Henry Huxley. His writings and travels gave him intimate contact with naturalists all over the world. Wealth and position provided him with a determined inner rectitude in matters of science or business, another trait that was admirable yet at times verged on egoism.

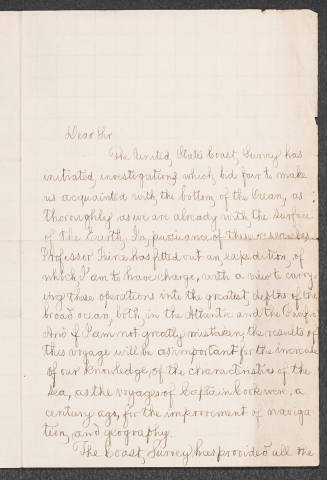

The great energy Agassiz brought to all his endeavors was most evident in his oceanographic work. He pioneered in the 1870s and 1880s several highly useful technological improvements for dredging marine specimens. Murray, who was a scientific confidant and biographer of Agassiz, affirmed in 1911 that all contemporary knowledge of "the great ocean basins and their general outlines" was due to Agassiz's work and his inspiration to others (Murray, p. 148). In ships of the U.S. Coast Survey, and in private vessels he rented or bought, Agassiz traveled hundreds of thousands of miles over the oceans of the world in the period from the mid-1870s through the early 1900s, each trip planned with meticulous care.

For nearly three decades at the end of his life, Agassiz's main interest related to studies of the origin and nature of coral reefs. This interest became an obsession; by the early 1900s "he had now visited practically all the coral reef regions of the world" (Agassiz, Letters and Recollections, p. 395), and his vessels sailed the Great Barrier Reef, the Pacific, and the Maldives with one central purpose: to overturn the views on coral reef formation put forth by Darwin and Dana in the 1840s. According to these naturalists, coral reef and atoll development was a continuous and universal process. Corals developed on the sides of sinking volcanic islands, slowly, and then marched upward until the island ultimately subsided and disappeared, leaving a coral reef or atoll in its place. Agassiz concentrated his attack on Darwin's work, calling it "twaddle" and "nonsense" and based on incomplete observation. For Agassiz, who conducted his observations across the world and over many years, reef and atoll formation and development was the result of building up or leveling down primarily through the local and unique actions of biological, chemical, and mechanical forces continuously in operation, understandable in different ways depending on the physical and geological conditions of specific regions. Universal explanations were impossible, Agassiz urged, affirming "I am glad that I always stuck to writing what I saw in each group and explained what I saw as best I could, without trying . . . to have an all embracing theory" (Murray, p. 151).

Agassiz's opposition to "all embracing" theory was similar to his complaint that radical evolutionists built "castles in the air" with their theories. Although naturalists like Murray made use of an early Darwin work in an effort to discredit the evolutionist, Agassiz claimed no such motive. But the vituperation of Agassiz's opposition and his Ahab-like quest to prove Darwin wrong may have been spurred by an effort to use his money and ships to attack Darwin on the comfortable ground of oceanography rather than the far more complex issues of evolution. But Agassiz never produced his "coral book," which was often promised as an overview of his researches, although he did describe specific sites.

Unfortunately for Agassiz's reputation, his determination to wrest explanation from the world's coral reefs had an unhappy effect. His observations proved often unreliable, his evidence weak, and many conclusions false; later scientists proved Darwin's theory correct. Yet, in the large view, Alexander Agassiz was a notable naturalist and entrepreneur, capable of breaking the paternal grip of his father's dominance, all the while honoring his name. In Henry Adams's words, "he was the best we ever produced, and the only one of our generation I would have liked to envy" (Agassiz, Letters and Recollections, p. 447). He died aboard the Adriatic while making a transatlantic voyage.

Bibliography

The Alexander Agassiz Papers are at the Museum of Comparative Zoology Archives, Harvard University. Other Agassiz materials are at the Houghton Library, Harvard University, and various collections at the Smithsonian Institutions Archives. Letters and Recollections of Alexander Agassiz, ed. George R. Agassiz (1913), is an important work edited by Agassiz's son. Among Agassiz's important works not mentioned in the text are A Contribution to American Thalassography: Three Cruises of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey Steamer "Blake" in the Gulf of Mexico, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the Atlantic Coast of the United States, from 1877 to 1880 (2 vols., 1888) and "The Coral Reefs of the Tropical Pacific," Museum of Comparative Zoology, Memoirs, vol. 28 (1903). A bibliography of his works is in George L. Goodale, "Biographical Memoir of Alexander Agassiz," National Academy of Sciences, Biographical Memoirs 7 (1912): 291-305. Sir John Murray, "Alexander Agassiz: His Life and Scientific Work," Museum of Comparative Zoology, Bulletin 54, no. 3 (1911): 138-58, is especially useful for Agassiz's coral reef work and his interpretations. See also David R. Stoddardt, "Alexander Agassiz and the Coral Reef Controversy" (unpublished manuscript, Berkeley, Calif.; 1992), and Mary P. Winsor, Reading the Shape of Nature: Comparative Zoology at the Agassiz Museum (1991), which contains useful discussions of Agassiz's scientific work and his position on evolution.

Edward Lurie

Citation:

Edward Lurie. "Agassiz, Alexander";

http://www.anb.org/articles/13/13-00015.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Wed Aug 07 2013 17:11:25 GMT-0400 (Eastern Daylight Time)

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Boston, 1822 - 1907, Arlington, Massachusetts

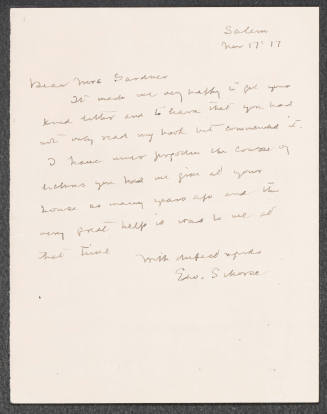

Portland, Maine, 1838 - 1925, Salem, Massachusetts

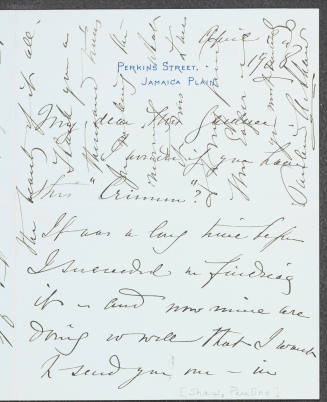

Neuchâtel, Switzerland, 1841 - 1917, Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts

Newport, Rhode Island, 1842 - 1901, Phoenix, Arizona

Kennebunk, Maine, 1856 - 1953, Pocasset, Massachusetts

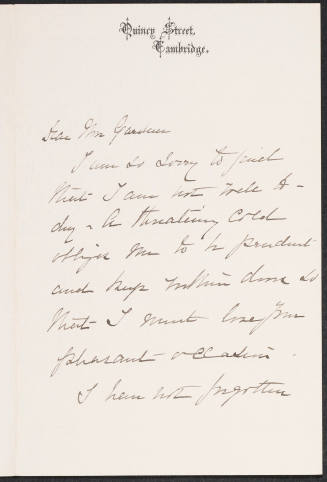

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1871 - 1933, Unknown

Schenectady, New York, 1828 - 1901

Southborough, Massachusetts, 1828 - 1854, Southborough, Massachusetts