William James Stillman

Schenectady, New York, 1828 - 1901

Stillman studied painting briefly under Frederic Church in 1848-1849. He sold his first landscape in the fall of 1849, and he then sailed to England arriving in January 1850. There he met Joseph Turner, John Ruskin, and the pre-Raphaelites. He studied art under Adolphe Yvon in Paris, where he was impressed by Henri Rousseau, Eugène Delacroix, and Jean-François Millet. Returning to the United States, Stillman was a disciple of Ruskin, and his faithful landscapes earned him the sobriquet "the American pre-Raphaelite" and an associateship in the Academy of Design. In 1855 he founded and edited the short-lived weekly, Crayon: A Journal Devoted to the Graphic Arts and the Literature Related to Them, for art essays and poetry. Around 1856 he organized the Adirondacks Club so he could spend his summers with his literary companions, including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, James Russell Lowell, and Louis Agassiz, the zoologist and founder of the Boston Comparative Zoology Museum. Stillman taught himself photography while wintering in Florida in 1857. He lived briefly with Ruskin, and although they eventually disagreed fundamentally on art, Stillman named his eldest son after Ruskin. In 1860 he married Laura Mack; they had three children.

During the Civil War, from December 1861 to the spring of 1865, Stillman was appointed American consul to Rome, then under papal jurisdiction. In 1865 he became American consul at Khaniá (Canea) in Crete, then under Ottoman rule and on the verge of savage civil strife. Stillman's reports on the events, especially the Cretans' self-annihilation rather than surrender at the monastery of Arkadi, were instrumental in persuading the great powers to send ships to rescue the noncombatants. His reports and his book, The Cretan Insurrection of 1866-7-8 (written in 1869-1871 but not published until 1874), constitute the primary sources for historians of this period. Under the stress of making the besieged consulate a haven for refugees, his wife, who apparently suffered from depression, committed suicide in 1868, after the birth of their daughter. Lacking the support of the new American government, Stillman resigned and began photographing sites in Crete, Athens, and Aigina. He published and sold his photographs as The Acropolis of Athens (1870) to pay off some of his debts, but he no longer felt able to paint landscapes.

In 1869 Stillman moved to England and lived briefly with Dante Rossetti. In 1871 he married Marie Spartali, the daughter of the Greek consul general in London; they had three children. He began contributing to various English newspapers and was the Balkans correspondent for the London Times after 1875. His compassionate though objective reports from Turkish-occupied Bosnia brought Montenegro to British public attention, raised money for the refugees, and forced the British government to take the principality and its aspirations into account. His letters and those of Arthur Evans, Balkan correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, were exploited by the former prime minister William Gladstone and the Liberal Opposition. Having given a telescope to the Slavic rebels, allowing them to see enemy locations and numbers, Stillman was instrumental in enabling them to defeat 20,000 Turks and capture a fortified citadel. He recounted these events in Herzogovina and the Late Uprising (1877).

On a commission from Scribner's in 1879, Stillman sailed from Ithaca to the Aegean and Crete and published his account as On the Track of Ulysses (1888). Asked by the Archaeological Institute of America to investigate excavation opportunities in Crete, he examined some recently exposed walls from the palace at Knossos. Although this project was rejected by both the Cretans and the Turks, his drawings of the walls and their inscribed masons' marks were the first records of Minoan architecture and are still central in scholarly arguments about what Evans later found at the site. Stillman took more photos of Athens, which he sold to Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema for use in his classically based paintings.

As the London Times correspondent in Greece, Stillman was offered a bribe by government officials, which he refused, not to disclose governmental corruption to his readers. While there, he was invited to accompany the commission to establish a new boundary along northern Greece, but he was too ill with cholera to take part. Later, when Greece was blockaded by England in May 1886, he helped the Greek prime minister call a cease-fire.

In January 1885 the American Numismatic and Archaeological Society requested that Stillman report on the authenticity and merits of the massive Cypriot collections sold by Luigi Palma di Cesnola to the New York Metropolitan Museum. He concluded that their usefulness was seriously diminished by a reckless attribution of provenances, repairs and alterations of items, and the nonexistence of the single deposit of the so-called treasure of Curium. After the published opinions of many art experts in the preceding years, Stillman's report stands out for its intelligence and archaeological insight. From 1886 to 1890, when Americans hoped to acquire the claim to excavate at Delphi, he pointed out in a series of letters to the Nation that the Greek authorities were exploiting the Americans while negotiating with the French, who had a prior claim to the site.

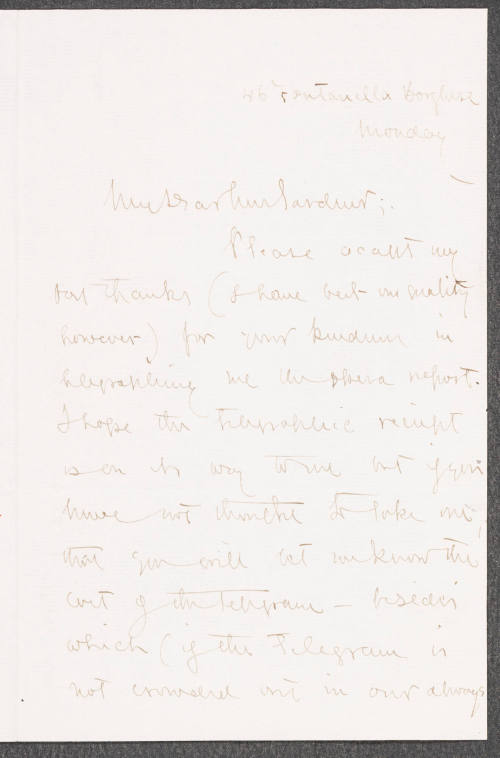

Asked by the London Times in 1889 to choose between Athens or Rome as a base, he chose Rome for family reasons, despite preferring Athens himself. In Italy he was a close observer of the premier, Francesco Crispi, who in January 1891 publicly honored Stillman for his help in negotiations with the English. He informed Crispi of a political conspiracy against him and exposed an Italian banking crisis before it became obvious to everyone. Crispi consulted him about political appointments and the events in Abyssinia. Stillman wrote a biography, Francesco Crispi, Insurgent, Exile, Revolutionist, and Statesman (1899). In 1898 he retired to Frimley Green, Surrey, England, where he wrote his autobiography before his death there. Of his portrait in volume 1, sketched in 1856, Lowell said, "You have nothing to do for the rest of your life but to try to look like it." The portrait in volume 2, sketched by his daughter in 1900, reveals his priorities were otherwise.

Stillman earned his living and reputation through his literary skills. His extensive writings reveal his compassion, objectivity, and humanity as well as the diversity of his talents. He gave assistance both to besieged refugees and to consulting English, Greek, and Italian politicians. As a London Times foreign correspondent, he was one of the earliest of the powerful journalists with political influence. Although frustrated as an artist through lack of training, he was an articulate art critic. He was intimately familiar with the American literary establishment and leading painters of the time, of whom he left noteworthy impressions. Exhibiting naiveté and faith, he acted without any thought of the consequences to himself, possibly taking after his father in this regard. Indeed, his apparent lack of concern for the needs of his first family may have mellowed with the death of his son in 1874, because he considered the wishes of his second family when choosing to live in Rome. Without being rich or elected to office, he made a difference in art, literary circles, Crete, Montenegro, Greece, and Italy.

Bibliography

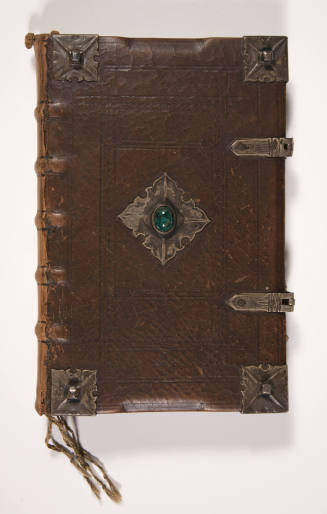

Stillman's consular dispatches are in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. A few were published by George G. Arnakis, "Consul Stillman and the Cretan Revolution of 1866," in the Transactions of the Second International Cretological Congress of 1966 (1969). In addition to innumerable published letters, essays, articles, and two manuals on photography, Stillman wrote Venus and Apollo in Paintings and Sculpture (1897); Billy and Hans, My Squirrel Friends: A True History (1897), a delightful and humane account of two squirrels he adopted; Little Bertha (1898); The Union of Italy, 1815-1895 (1898); and The Old Rome and the New and Other Stories (1898), a collection of essays. His Autobiography of a Journalist (1901) is candid and full of reminiscences of some of the eminent people he encountered but somewhat vague on the chronology of events. Obituaries are in the New York Evening Post, 8 July 1901, and the London Times, 9 July 1901.

D. J. Ian Begg,

Back to the top

Citation:

D. J. Ian Begg, . "Stillman, William James";

http://www.anb.org/articles/04/04-01240.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:13:05 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Boston, 1849 - 1921, Dublin, New Hampshire

Boston, 1871 - 1961, Boston

Beverly, Massachusetts, 1851 - 1930, Beverly, Massachusetts

Urumiah, Persia, 1852 - 1908, Cambridge, Massachusetts

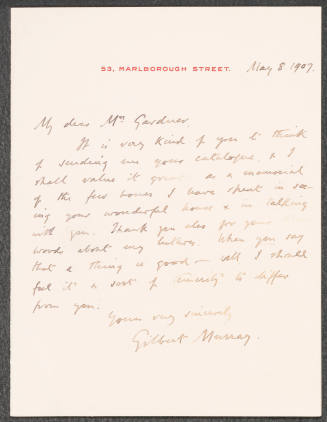

Sydney, Australia, 1866 - 1957, Boars Hill, England

Hanover, New Hampshire, 1864 - 1944, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge, 1827 - 1908, Cambridge