Image Not Available

for Frances Hodgson Burnett

Frances Hodgson Burnett

Manchester, England, 1849 - 1924, Plandome, New York

Burnett, Frances Eliza Hodgson (1849–1924), children's writer and novelist, was born on 24 November 1849 in Cheetham Hill, Manchester, the third child and eldest daughter in the family of two sons and three daughters of Edwin Hodgson (1816–1854) and his wife, Eliza, née Boond (1815–1870). Edwin Hodgson, wholesaler of decorative ironmongery, died aged thirty-eight. His widow struggled to run the business herself until her brother, who had established a dry-goods store in Knoxville, Tennessee, USA, persuaded her in 1865 to emigrate with the children. The early years in Tennessee were hard and the family was frequently hungry, but in 1868 Frances, who from her earliest childhood had been a compulsive inventor of romances, sold her first two stories to Godey's Lady's Book, raising the money for paper and postage by selling wild grapes. Until her marriage she supported the family by a constant stream of magazine stories, her only object, as she said herself, being remuneration.

On 19 September 1873 Frances Hodgson married an ophthalmologist, Swan Moses Burnett (c.1847–1906), the son of John Burnett, a Tennessee physician, and his wife, Lydia Peck. They lived first in Knoxville, and moved to Washington, DC, in 1877. There were two sons, Lionel (b. 1874) and Vivian (b. 1876). Mrs Burnett took her marital duties lightly, and though she did not formally end the marriage until 1898, from early days she made a practice of absenting herself from her family, often for months on end, travelling in North America and Europe, and spending long periods in England, where she moved in high society and had many literary friends, Henry James and Israel Zangwill among them. In spite of frequent and prolonged separation from them, she was devoted to her sons and they to her, and the death of Lionel, from tuberculosis, in 1890 was a shattering blow. Early in 1900 in Genoa, Italy, she married Stephen Townesend (1859–1914), a young physician with stage aspirations whom she had tried to help, and who in his turn assisted her in her business affairs. Ten years younger than his wife, he was the youngest son of the Revd George Fyler Townesend and grandson of the Revd George Townsend (1788–1857), a redoubtable cleric who had travelled to Italy in 1850 to try to convert the pope. They were divorced in the following year, and she continued to publish under her first married name.

Frances Hodgson Burnett had early had to turn herself into ‘a pen-driving machine’ (Burnett, 75) to support the ever-increasing opulence of her lifestyle, and her adult fiction (she wrote more than twenty novels and innumerable short stories) for the most part is facile and superficial. She was never to equal her first novel, That Lass o' Lowrie's (1877), a robust account of a Lancashire mining community in which she had taken great care with background and dialect, though Through One Administration (1883), a study of a failed marriage against a turbulent background of Washington political life, was noteworthy, and the much shorter The Making of a Marchioness (1901) is an effective indictment of Edwardian society. She adapted many of her novels, including the first, for the stage, with mixed success.

Frances Hodgson Burnett's first children's book, Little Lord Fauntleroy, appeared in 1886. This account of how a sturdy and friendly young American wins the heart of the irascible and hostile earl of Dorincourt, the grandfather who has hitherto refused to see him, acquired a largely undeserved reputation for sentimentality. This was in part due to Reginald Birch's illustrations which kept the boy always in black velvet and lace, even when he was riding his pony, and in part to the intense relationship between mother and son; Frances Hodgson Burnett here had in mind herself and her son Vivian, upon whom Fauntleroy himself was modelled. It was a huge success, stage and film versions were made of it, and it led to thousands of unwilling boys being dressed in black velvet suits. When E. V. Seebohm presented it as a play in London in 1888 without her permission, she challenged him in the courts and succeeded in getting the current copyright laws changed.

‘She wanted to be in the land of make-believe as often and as long as possible’ (Burnett, 331), her son Vivian said of her. In her books this is to be found at its most extreme in Sara Crewe (1888)—expanded, following the stage version, as The Little Princess (1905)—a Cinderella story where a bullied little drudge at a girls' school is restored to riches and esteem and the tyrannical headmistress humiliated. Her finest book was undoubtedly The Secret Garden (1911), which achieved classic status. This describes how two disagreeable and unloved children are transformed by the discovery of a hidden garden which they appropriate and which they watch springing into life as the year advances. The garden depicted with such passionate intensity is based partly on an abandoned one she had seen near her Manchester home when she was a child, and partly on the rose garden at Maytham Hall, Rolvenden, near Tenterden, Kent, a house she rented for many years and last visited in 1907.

Frances Hodgson Burnett had to the last a youthful enthusiasm, an erect carriage, and a firm step. Stocky in childhood, she became stout in middle age and the auburn of her hair was maintained by henna. She always loved clothes and dressing-up, particularly in ‘clinging, trailing chiffon things with miles of lace on them’ (Thwaite, 212). She took American citizenship in 1905. A libel action brought by her nephew's wife brought her much unpleasant notoriety in 1918. ‘She has shattered the mirrors which might betray her to herself’ was one of the milder comments. The last years of her life were divided between Bermuda and Plandome, Long Island, New York, USA, where she built herself an Italian-style villa and where she died on 29 October 1924. She was buried at God's Acre, Roslyn, Long Island, and a memorial to her was placed in Central Park, New York city, consisting of statues of a boy and girl.

Gillian Avery

Sources

A. Thwaite, Waiting for the party (1974) · V. Burnett, The romantick lady (1927)

Archives

BL, literary MSS, Add. MSS 41678–41681

Likenesses

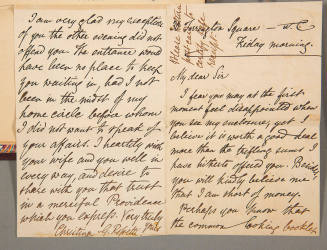

Barraud, photograph, NPG; repro. in Men and Women of the Day, 1 (1888) [see illus.]

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Gillian Avery, ‘Burnett, Frances Eliza Hodgson (1849–1924)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/37247, accessed 10 Oct 2017]

Frances Eliza Hodgson Burnett (1849–1924): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37247

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1835 - 1894, Appledore Island, Isle of Shoals, Maine

Ecclesfield, England, 1841 - 1885, Bath, England

American, 1869 - 1944

London, 1830 - 1894, London